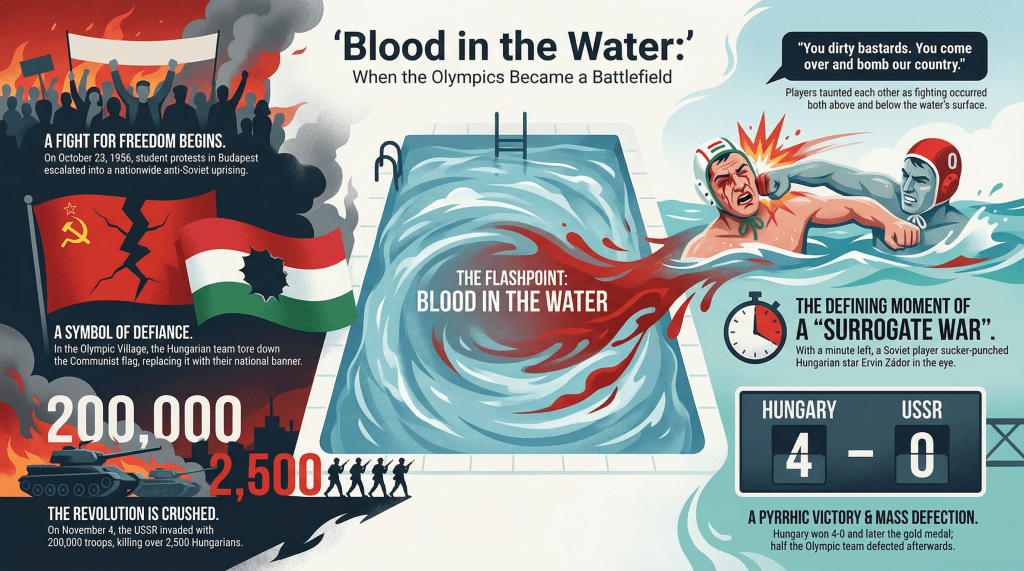

There are moments in history when a single image carries the weight of an entire generation’s grief. Not the kind of image museums print on postcards, but the kind that sticks somewhere behind the eyes. In December of 1956, during the Melbourne Olympic Games, a photographer caught Hungarian water polo player Ervin Zador climbing out of the pool with blood streaming down his face from a crescent shaped cut over his right eye. He looked stunned, angry, and heartbreakingly young. The photograph flashed across the globe, and for a brief moment the world understood that the pool in Melbourne had become another battlefield in a much larger and darker struggle. The match between Hungary and the Soviet Union was supposed to be a semifinal for a gold medal. Instead, it became the kind of surrogate war humans seem to stage whenever they are trying very hard not to stumble into a real one.

Zador’s scar was not dramatic. It was a small curve, the shape of a thumbnail. Yet it became one of the most famous wounds in Olympic history because everyone who saw it understood that it was more than a sports injury. A Soviet player had punched him in the face, and the blow arrived barely a month after Soviet tanks had rolled into Budapest and crushed the Hungarian Revolution. It was not difficult to connect the dots. The most famous pool in Australia had turned into a symbolic Budapest street, and a young athlete’s blood had become a reminder of a national tragedy. Sports rarely escape politics, no matter how much we pretend they do, and on that December day the pretense fell apart.

That is the strange thing about the Olympics. They promise peace and understanding. They offer flags, fanfare, and the sort of cheerful music that suggests humans might yet learn to get along. Then something like 1956 crashes through the door and reminds everyone that old resentments tend to float, even in chlorinated water. The match between Hungary and the Soviet Union was more than rough play. It was a collision of grief, pride, and anger. It was also a small act of defiance by a nation that had just been reminded it lived under someone else’s boot.

Hungary had already spent the years after the Second World War learning what life looked like under Soviet domination. The country that once looked to the West now found itself locked inside the Soviet sphere. That shift came with a new political order that dressed itself in the familiar vocabulary of socialist liberation, but quickly revealed teeth. By 1949, the Hungarian People’s Republic had been established under the leadership of Mátyás Rákosi. Rákosi styled himself as Stalin’s best student. Unfortunately, he took that description seriously. He oversaw a climate of fear driven by the State Protection Authority, known as the ÁVH. The ÁVH did not bother with subtlety. They spied, arrested, interrogated, tortured, and made people disappear when needed. They also made people disappear when it was not needed. They were thorough in every sense of the word.

Hungarians knew something was slipping away. Their political freedoms had already evaporated, and their economic hopes were next. Forced industrialization drained the country’s resources, while bureaucrats did what bureaucrats often do when given ideological authority and little oversight. They mismanaged almost everything. By the early 1950s, Hungarian workers earned only two thirds of what they had earned before the war. They paid reparations, joined COMECON, and endured a rigid system that insisted a brighter future was just around the corner while offering little evidence of it. The propaganda talked about progress. The empty shelves talked about something else.

Then Stalin died in 1953, and Nikita Khrushchev began to reshape the Soviet empire. He called his approach De Stalinization, which sounded like a cleaning process. He loosened the grip on Eastern Europe a bit, and Hungary briefly believed that a gentler tide might be turning. Imre Nagy was named prime minister. He was no liberal hero, but he offered a kinder face than Rákosi. He spoke about reform, which made him immediately popular and equally dangerous. Any hope that Hungary might drift toward genuine self determination was short lived. Nagy was removed in 1955, and the old guard returned. They brought their old suspicions with them, and Hungarians felt the future narrow again.

The Hungarian people still held a quiet belief that things could change, and by the autumn of 1956 that belief sparked into something brighter. University students marched in Budapest on October 23. They carried a list of modest demands that called for reforms, free speech, and an end to Soviet domination. They walked toward the Magyar Rádió building to broadcast their message. The ÁVH opened fire on them. The first student to fall became the first martyr of the uprising, and Hungary erupted. Crowds tore down the massive Stalin Monument in Budapest, which had always seemed to loom like a silent warning over the city. It collapsed into pieces, a symbol of a larger collapse the people hoped would come next.

For a few brief days the revolution seemed possible. Imre Nagy returned as prime minister. He disbanded the ÁVH and promised free elections. On November 1 he declared Hungary’s intention to leave the Warsaw Pact entirely. That was the moment when the dream shattered. The Soviet Union launched Operation Whirlwind on November 4. Tanks rolled into Budapest. Soldiers poured into the country. The uprising was crushed with overwhelming force. Streets that had echoed with chants now echoed with gunfire. By the end of the violence more than five thousand Hungarians were dead, and many more were wounded or imprisoned. Nagy was arrested, and years later he was executed. Two hundred thousand Hungarians fled the country in the largest refugee movement Europe had seen since the war.

While Hungary burned, the water polo team trained at a remote camp outside Budapest. They heard rumors, but they had no idea how bad the situation had become until they reached Melbourne. They arrived in a world that was celebrating athletic joy while their own country mourned. They walked into the Olympic Village, removed the Communist flag from above their quarters, and replaced it with the flag of Free Hungary. They were young, proud, and angry. They knew their families were in danger. They had no idea if they would ever see them again. Their coach told them that they were carrying the hopes of a wounded nation and that they needed to win the gold medal not for glory but for dignity. That sort of pressure does not help an athlete relax, but it does sharpen purpose.

Water polo in Eastern Europe has never been a gentle game. The Hungarians approached it the way some people approach a duel. The Soviets approached it as a test of national strength. The two sides had met many times, and each match carried more emotion than most international conflicts. The Hungarians always played with an edge. The Soviets always played with muscle. By 1956 these two teams had become something larger than athletes. They represented clashing worlds, and both sides understood it.

The Melbourne Games became a political echo chamber. The Netherlands, Spain, and Switzerland refused to participate because of the Soviet invasion of Hungary. The boycott was public and dramatic, which probably gave Moscow a headache but did not change events on the ground. The Hungarian players moved through the Olympic Village with the feeling that the world was watching them. They were not wrong. Every journalist wanted to know how they felt about the invasion. That sort of question has no safe answer, especially when your government has just been crushed. The players kept their comments brief and their feelings guarded. Then the semifinal bracket announced the match that everyone expected and dreaded. Hungary would face the Soviet Union.

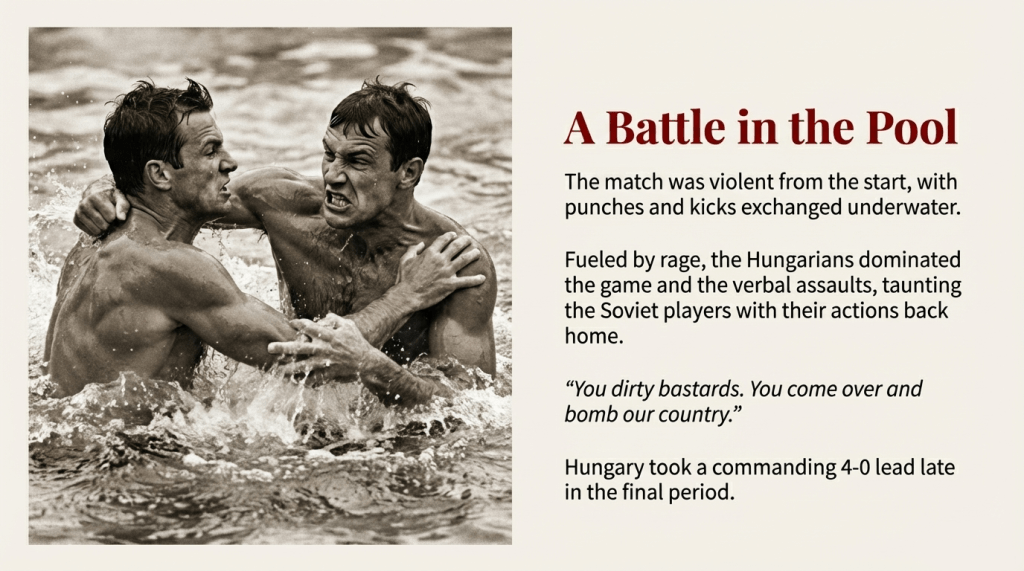

On December 5, 1956, more than five thousand spectators filled the natatorium. Most were Hungarian expatriates who had fled years earlier or had come from as far away as Australia’s small Hungarian community could travel. Their shouts filled the air before the first whistle. The Hungarian captain refused to shake hands with the Soviet captain. The crowd roared approval. The Soviets stood quietly. They had heard the insults and understood the emotion, but they were there to play a game that had suddenly become a theater of national defiance.

Once the match began, the tone shifted from tense anticipation to outright hostility. Hungarian players swam hard and fast, taunting the Soviets with lines that would raise eyebrows in any polite company. They shouted that the Soviets had bombed their country. The Soviets responded with physical play that pushed every boundary of the rules. Within minutes, elbows, fists, and legs were striking beneath the surface, which is exactly where water polo fights usually begin. The referee did what referees often do in these situations. He tried to pretend he did not see everything.

Hungary built a quick lead. The score rose to four to zero, and the Soviets grew more frustrated. Two Soviet players were sent to the penalty box for slugging Hungarian players. The crowd rewarded each penalty with a roar that shook the building. The Hungarian players sensed victory. They also sensed danger, which in water polo often arrives as a badly aimed fist.

With about a minute left in the match, Ervin Zador surfaced near the edge of the pool. He heard a whistle, turned his head, and in that vulnerable instant a Soviet player rose out of the water and punched him squarely in the face. The impact split the skin above his right eye. Blood poured into the water. For a moment the arena froze. Then the Hungarian crowd surged toward the pool. They were enraged, and they wanted revenge. The officials halted the match instantly. Police moved in to escort the Soviet team from the deck. Zador climbed out, holding his face, his eye swelling shut. Flash bulbs burst around him. Someone handed him a towel. Someone else told him the match was over and Hungary had won.

He later said that he had not felt fear until he looked up and saw hundreds of Hungarians rushing toward him. They were not angry at him, but anger is a blunt instrument, and it does not always choose good targets. The referee’s decision to end the match probably prevented a riot. The Soviets left quickly, and the arena slowly quieted.

Hungary advanced to the final, where they defeated Yugoslavia two to one. Zador did not play. He sat on the pool deck with eight stitches above his eye and watched his teammates win the gold medal they believed their country needed. When he stepped onto the medal platform he wore street clothes. He shook, laughed, and cried at the same time. He had dreamed of returning home as an Olympic champion. Instead he knew he could never return at all.

Zador was only one of many Hungarian athletes who faced that choice. Of the one hundred seventy five Hungarian Olympians in Melbourne, forty five sought asylum in the West. That number included half of the entire water polo team. The Hungarian community in Melbourne opened its doors. They offered money, jobs, apartments, and friendship. Some athletes remained in Australia. Others traveled to the United States or Europe. Zador chose the United States. He found the level of water polo play in America surprisingly primitive, which seems reasonable considering the sport had never captured the American imagination the way it had captured Eastern Europe. He became a swimming coach and helped train a young Mark Spitz, who would later become a global Olympic legend. Zador eventually brought his parents and brother to America, and he discovered that freedom allowed him to speak openly about his experiences, which he considered a gift worth more than medals.

The Hungarian government took longer to reflect on what the mass defections meant. For a state that prided itself on discipline and control, the sight of dozens of their best athletes fleeing on the world stage became a public relations calamity that no propaganda department could spin. Officials realized that if they wanted to keep their athletic talent, they would need to soften the hard edges of their policies. The government began to offer athletes more opportunities, more travel, and more autonomy. Not because they believed in those freedoms, but because losing them again would be worse. A quiet shift took place within Hungarian sport, one that reflected a small, reluctant lesson in human nature. People do not like cages, even when the bars are painted with patriotic slogans.

The story of 1956 has continued to echo. Nearly fifty years later it inspired two films. A documentary called Freedom’s Fury revisited the match and explored Zador’s journey. It was narrated by Mark Spitz, which offered a poetic sense of continuity. It also allowed surviving members of both teams to reconnect. Some of the Soviet players admitted that they had lived under their own forms of oppression. The documentary treated both sides with a sense of humility and acknowledged the way politics had shaped their lives. A Hungarian feature film titled Children of Glory retold the revolution and the match with dramatic flair, capturing the spirit of a moment when a small nation tried to reclaim something much larger than itself.

Zador often reflected on the intersection of sports and politics. He said, I wish sports could be exempt from politics. But that is just a dream. It will never happen. He was right, although the wish itself remains noble. Humans bring their whole selves into the arena. They bring pride, anger, fear, and hope. They also bring memories of the wounds that shaped them. Perhaps that is why the image of a young man bleeding from a curved wound over his eye still holds such power. It reminds the world that even in moments designed for celebration, history reaches out with a long shadow.

The Melbourne match mattered because it offered a moment of truth. Hungary had been crushed, but its athletes found a way to assert dignity in a pool half a world away from home. The Soviet Union had won the military victory, but it could not win the symbolism. That belonged to a handful of young men swimming in clear water stained by a single drop of blood.

History does not offer easy moral lessons, although people often try to shape them. The 1956 match did not change the course of the Cold War. It did not free Hungary. It did not soften the Soviet system. Yet it carved a place in collective memory because it revealed something about the human spirit. When everything else is taken away, people still look for ways to assert their identity. Sometimes they do it with flags. Sometimes with songs. Sometimes with a water polo match played before thousands who understand exactly what is at stake.

The world watched Hungary in 1956. It watched Soviet tanks crush a revolution, and it watched young Hungarians refuse to submit even when the odds were impossible. It watched them swim, shout, fight, and bleed. The Melbourne pool became a small stage on which a larger tragedy played out. The crowd roared because they knew the match was never really about water polo. It was about a nation trying to hold onto its soul.

There is a lyrical quality to history when examined with enough distance. The wounds become symbols. The shouts become echoes. The faces become portraits framed by whatever hindsight decides to remember. Yet something remains stubbornly real. A young man touched his face and felt warm blood pour between his fingers. A crowd surged forward believing they were witnessing more than a game. A referee blew a whistle trying to preserve a fragile notion of order. None of that can be softened. None of it can be rewritten into something tidy.

The story still resonates because it reveals what happens when politics and sport collide. People like to imagine that athletic competition exists in a separate realm where flags are harmless decorations and rivalries are friendly. The truth is more complicated. Humans bring their anger and their longing into every arena. They do it because they have no other place to put those feelings. And every so often, the world receives an image that sums it all up. A single drop of blood on an athlete’s cheek becomes a history lesson you cannot ignore.

Zador did not want to be remembered for that wound. He wanted to be remembered as an athlete, a coach, a man who built a life in a new country. Yet the world continues to remember him that way because that is how history works. It chooses symbols without asking permission. The photograph of his face became a shorthand for the Hungarian Revolution, for Soviet oppression, for the raw power of human courage. It also became a reminder of how deeply people can feel about their homeland, even when they are thousands of miles away.

The 1956 water polo match between Hungary and the Soviet Union remains one of the most intense and unforgettable events in Olympic history. It proved that global politics can slip into the pool when nobody is looking. It revealed the stubbornness of national pride. It showed that a sport played in water can reach depths that have nothing to do with swimming.

The scars of 1956 have faded in the real world, but the story remains. It lingers like the scent of chlorine that clings to an athlete’s skin long after the match ends. The tale sits quietly in the corner of the Olympic record book, waiting for someone to dust it off and remember what happened when two nations tried to settle something much larger than a game. History does not move in straight lines. It loops and wanders. It surprises. And every now and then, it leaves behind a curved scar above an eye, a reminder that the water may be clear but the world never is.

Leave a reply to sopantooth Cancel reply