On August 14, 1959, in a Chicago meeting room far from the bright lights and big stadiums of the NFL, a small group of stubborn, ambitious men shook hands on something most thought was doomed. They called themselves “The Foolish Club,” not because they lacked resources or vision, but because they knew exactly what they were up against. The NFL had just twelve teams, no appetite for expansion, and every intention of keeping it that way. Lamar Hunt, a young Texas oilman, had tried to bring an NFL team to Dallas. The league turned him down. So he rounded up others who had also been left at the doorstep, men like Bud Adams in Houston, Bob Howsam in Denver, Harry Wismer in New York, and Barron Hilton in Los Angeles. They were not looking for a fight, but they were willing to have one if the NFL forced their hand. By the time that first meeting ended, a rival league had been born.

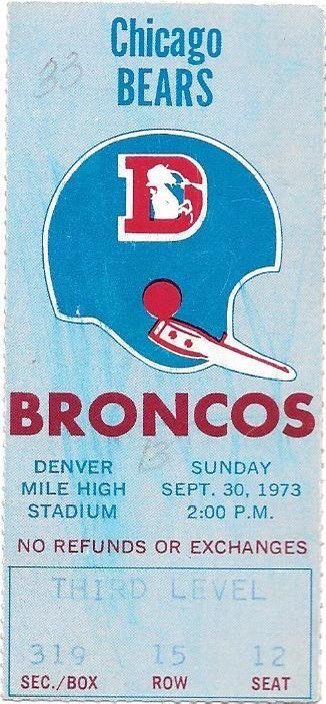

I grew up in the echo of that meeting, though I didn’t know it at the time. My Denver Broncos were part of that original lineup. They were a tough sell in the early days. The uniforms were garish, the stadium seats were often empty, and the record books weren’t kind. Denver won the very first regular-season AFL game, 13–10 over the Boston Patriots, but that was more a curiosity than a sign of dominance. The team never had a winning season in the league’s ten-year run and came close to folding in 1965 before a local ownership group took over. Signing Floyd Little in 1967 gave Denver not just a star player but a reason to believe the city could keep its franchise. For a kid growing up in the late 60s and 70s, the Broncos were my team whether they won or not, because they belonged to us. And they belonged to the AFL.

That first AFL season in 1960 was a little wild. The Houston Oilers signed Heisman Trophy winner Billy Cannon away from the NFL’s Los Angeles Rams in a contract battle that ended up in court. The league had a TV contract with ABC that kept it afloat, but attendance was spotty. The Raiders barely drew 10,000 fans a game. The Titans of New York had such poor crowds that the owner would move people down closer to the field so it looked better on television. Yet the league pressed forward, scoring occasional victories in talent battles with the NFL and winning over fans who liked the faster, more open style of play. Passing mattered more here. Uniforms popped with color. The two-point conversion was allowed. In short, it felt different.

By the mid-60s, the AFL had started to shed its “upstart” label. Signing Joe Namath in 1965 gave the league not just a quarterback, but a showman who could stand toe to toe with anything the NFL had to offer. The bidding war for college stars drove salaries higher in both leagues. NBC took over the television rights in 1965, bringing more money and exposure. The real turning point came with the merger agreement in 1966. Both sides were bleeding cash over player contracts, and cooler heads decided they would be stronger together. The deal created a common draft and an annual championship game between the leagues. The first two Super Bowls went to the NFL’s Green Bay Packers, which reinforced the idea that the AFL was still second best. Then came January 1969, when Namath guaranteed his Jets would beat the Baltimore Colts in Super Bowl III. He delivered. That game, and the Kansas City Chiefs’ win over the Minnesota Vikings the next year, erased the last doubts about the AFL’s quality.

For Denver, the merger brought a new reality. We joined the NFL’s American Football Conference in 1970, along with every other AFL team. The rival league that had given us a place to play was now gone in name, but for a while the spirit lingered. Back then, the AFL teams were like cousins. You rooted for them when they played NFL clubs. I remember the Chiefs holding up a “Go Jets” sign after New York stunned Baltimore. It wasn’t about the standings. It was about proving that the AFL could stand on equal footing. In those moments, it didn’t matter if it was Kansas City or Buffalo or Oakland. They were ours.

That spirit didn’t last forever. I knew it was truly gone the day Broncos owner Pat Bowlen told us as fans not to wish any other AFC West team success in the playoffs. He wasn’t wrong from a business standpoint. The NFL had become a different animal by then. Rivalries were too important for ticket sales, too much money was on the line to share goodwill with your competition. But for those of us who grew up in the AFL era, that was the last little ember going out.

The AFL didn’t just merge into the NFL. It forced change. Salaries went up. TV coverage got better. Rules loosened to favor passing and scoring. Cities like Denver, Buffalo, and Kansas City got teams that became part of the fabric of the game. The Broncos eventually rose from league doormat to Super Bowl champions. But for me, no matter how many Lombardi Trophies sit in the team’s case, I’ll always remember when we were the underdogs in the orange and brown, playing in a league built on defiance, and pulling for anyone who carried that same banner.

Leave a reply to FTB1(SS) Cancel reply