It was a clear spring day, May 7, 1915, when a British ocean liner—the RMS Lusitania—slipped beneath the waves off the southern coast of Ireland. She had left New York six days earlier, bound for Liverpool, and was now just hours from her destination. On board were nearly two thousand souls—men, women, children, businessmen, families, and a significant number of Americans. The war in Europe had raged for almost a year, but for most Americans, the Atlantic still felt like a wide and safe buffer. That illusion was shattered in under twenty minutes.

Listen to the Article:

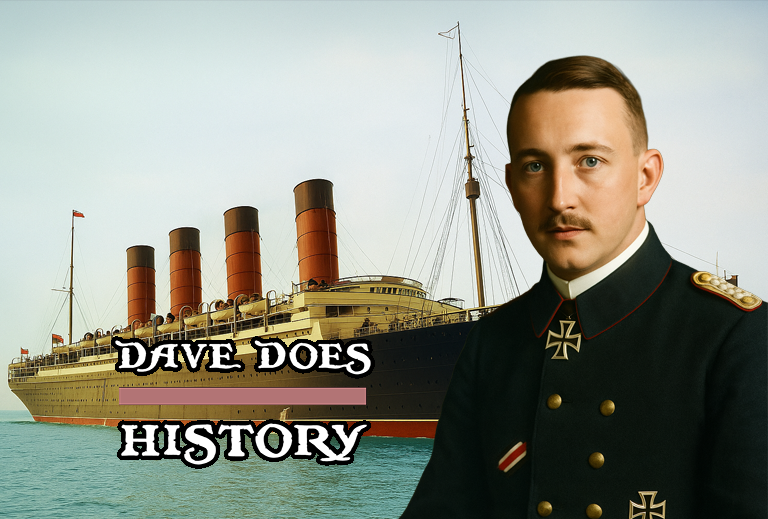

The Lusitania was no ordinary passenger ship. At the time of her launch in 1906, she was the pride of the Cunard Line and the largest ship in the world. She was sleek, fast, and luxurious, boasting elegant staterooms and state-of-the-art design. Her four massive funnels towered like smokestacks of progress. She represented everything the Edwardian era valued—speed, elegance, and imperial pride. But she was also something more than a luxury liner. In the shadowy agreements between the British government and private shipping firms, the Lusitania had been fitted to serve as an armed merchant cruiser during wartime. Though she never carried guns on deck, she had the structural modifications that allowed for them. And on this particular voyage, she carried a cargo of rifle cartridges and artillery shells along with her civilian passengers.

To the German High Command, that made her a legitimate target.

Patrolling the waters south of Ireland that day was a German U-boat—SM U-20. Her commander was Kapitänleutnant Walther Schwieger, a 30-year-old officer with a growing reputation. Schwieger had joined the Imperial German Navy in 1903, and by 1915, he had become one of its most effective and controversial submarine captains. Schwieger had a policy, unofficial but practiced—he did not hesitate. He did not always seek to identify ships before attacking. His method was swift, aggressive, and in the minds of many, ruthless.

That afternoon, Schwieger spotted a large ship approaching through the periscope. He noted her four funnels and two masts, classic indicators of a passenger liner. He estimated the distance—about 700 meters—and fired a single torpedo. It struck the Lusitania on the starboard side, just beneath the bridge. What happened next remains a matter of heated historical debate. Almost immediately after the torpedo hit, a second, far more violent explosion tore through the ship. Some believe it was caused by coal dust igniting, others suspect a boiler exploded. Still others point to the munitions on board as the source.

Whatever the cause, the result was horrific. The Lusitania listed sharply and began to sink. In just eighteen minutes, she disappeared beneath the sea. Of the 1,959 people aboard, 1,198 perished. Among the dead were 128 American citizens.

Schwieger watched the carnage through his periscope. He later wrote in his war diary that he could not bring himself to fire a second torpedo into what he described as “this mass of humans desperately trying to save themselves.” He ordered U-20 to dive and move away.

The news of the sinking hit the United States like a thunderclap. Americans, who had so far watched the war from a distance, suddenly found themselves drawn into the emotional and moral gravity of the conflict. The deaths of so many civilians—particularly Americans—prompted a firestorm of public outrage. President Woodrow Wilson’s administration formally protested to the German government. Kaiser Wilhelm II, upon reading the American diplomatic note, scrawled in the margins his disdain: “Utterly impertinent,” “outrageous,” “insolent.” Still, the political pressure worked. Germany agreed to suspend its policy of unrestricted submarine warfare, at least temporarily, and ordered that passenger liners should not be targeted without warning.

For the British government, the Lusitania became a symbol of German barbarity. Posters and newspapers decried the “murder on the high seas,” and the event was used to galvanize enlistment, bolster support for the war, and paint Germany in the darkest possible light. The fact that the ship had been carrying munitions was quietly acknowledged in official circles but rarely emphasized in public messaging. In the court of world opinion, Germany had committed an unforgivable atrocity.

As for Schwieger, he returned to sea. Later in 1915, he torpedoed the RMS Hesperian, a ship serving as a hospital transport. It was another black mark, one that infuriated the Allies and strained Germany’s efforts to keep America out of the war. But Schwieger seemed undeterred. In 1916, he was transferred to a new submarine—U-88—and continued his aggressive patrols. In total, he would command three submarines, complete 34 missions, and sink 49 ships, totaling over 183,000 gross tons.

Schwieger’s style was not universally admired within the German Navy. He had become something of a liability, a symbol of the tension between effective warfare and diplomatic fallout. But he was also decorated with the Pour le Mérite, the Iron Cross, and other honors. He remained, to Germany’s military elite, a skilled officer doing his duty.

His end came abruptly. On September 5, 1917, U-88 likely struck a mine in the North Sea off the coast of the Netherlands. All 43 hands were lost, including Schwieger. There was no wreckage recovered, no dramatic final entry in a war diary. Just silence, and the cold, indifferent sea.

U-20, the submarine that had launched the torpedo that sank the Lusitania, had already met her own fate. In November 1916, she ran aground off the Danish coast near Thorsminde after suffering engine trouble. Her crew scuttled the boat, and over the following years, the Danish government dismantled and eventually destroyed what was left of her. Her conning tower now rests in a small museum in Denmark, a relic of steel and memory.

The sinking of the Lusitania did not immediately bring the United States into the war. That would come nearly two years later. But it changed everything. It stripped away the illusion that the war could remain a European affair. It showed the world what modern war could do to civilians. And it added a moral dimension to the conflict that could not be ignored.

Walther Schwieger remains a complicated figure. To some, he was a cold-blooded killer who violated every rule of maritime decency. To others, he was a soldier following orders in a brutal war that spared no one. History has not offered a simple judgment. But what is clear is this: when U-20 fired her torpedo that afternoon in May 1915, she did not just sink a ship. She helped change the tide of a world war.

Leave a reply to James Elkington Cancel reply