It began on a spring day in Beijing, May 4th, 1919. More than three thousand students from thirteen universities gathered in Tiananmen Square, not to celebrate or observe a holiday, but to protest. They were angry, frustrated, and determined. Their government had failed them, their nation had been betrayed, and they were not going to remain silent. That day would not only be remembered for a student demonstration, but as the birth of modern China.

Listen to the article:

To understand the fire that erupted that day, one must understand the slow burn that led up to it. China in the early twentieth century was a fractured and humiliated giant. The Qing Dynasty, which had ruled for over two hundred and fifty years, had collapsed in 1911, leaving a republic in name but chaos in practice. Warlords ruled the provinces, foreign powers carved out spheres of influence, and the central government in Beijing was largely impotent. Confucianism, once the bedrock of Chinese society, began to feel stale and obsolete to a generation that had watched its traditions fail to protect the nation.

In this climate of disillusionment, a new movement began to stir. It was called the New Culture Movement, and it was led by bold thinkers like Chen Duxiu and Hu Shi. These men did not just want new leaders; they wanted a new way of thinking. Out with blind obedience to elders, and in with reason, science, and democracy. Out with the classical Chinese language that only the elite could understand, and in with the vernacular language spoken by the people. They called for a cultural revolution before any political one could take root. Their journal, New Youth, became the beating heart of a growing call for national awakening, attracting young minds eager to reshape China from the ground up.

Meanwhile, across the sea, the First World War was coming to an end. China had joined the Allied powers in 1917, hoping that its contribution of over 140,000 laborers to the Western Front would earn it respect and a seat at the table. These Chinese laborers, known as the Chinese Labour Corps, dug trenches, repaired roads, and performed countless tasks behind the scenes that were crucial to the Allied war effort. The Chinese delegation arrived at the Paris Peace Conference with modest hopes. They wanted German-controlled territories in Shandong Province returned to China. Instead, they were told those lands would go to Japan.

The betrayal cut deep. Japan had already humiliated China with its infamous Twenty-One Demands in 1915, a set of aggressive economic and territorial requirements forced on a weak Chinese government. Now the Western powers, led by Woodrow Wilson and his vaunted Fourteen Points, had turned a blind eye to Chinese interests. Wilson spoke of self-determination, but when push came to shove, he and the other leaders—Clemenceau of France and Lloyd George of Britain—sided with the Japanese. China was not even allowed to present its case effectively. It was a bitter reminder that even in victory, China remained powerless in the eyes of the world.

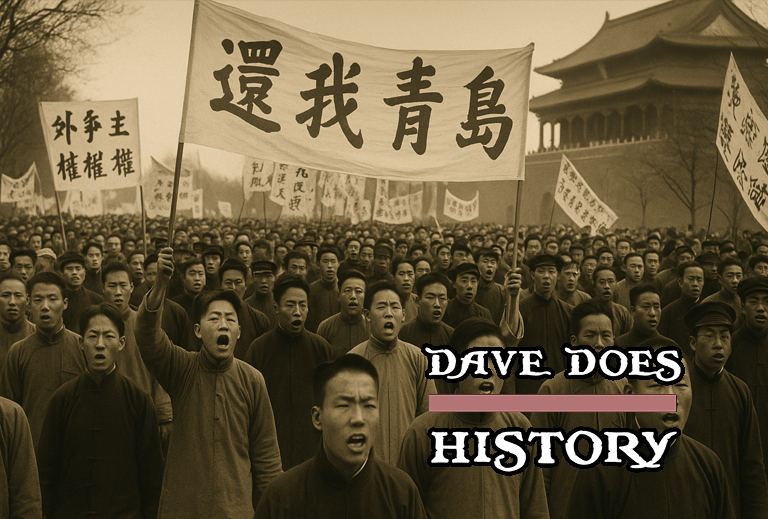

News of the decision reached China in April of 1919. The students of Beijing did not wait for their elders to act. On May 4th, they took to the streets with five demands: oppose the transfer of Shandong to Japan, awaken the national spirit, call for mass protest, establish a student union, and demonstrate publicly against the Treaty of Versailles. They shouted slogans like “Return Qingdao to us” and “Down with the traitors.” The anger was not only directed outward, but inward—toward their own government and the officials who had allowed this to happen.

Some of the students stormed the home of a pro-Japanese minister, burned his house, and beat his servants. The authorities responded with arrests and beatings of their own. But the spark had already caught fire. The protests spread to other cities. In Shanghai, in Guangzhou, in Tianjin, students walked out of class and into the streets. They were soon joined by merchants and workers, who began strikes and boycotts of Japanese goods. The movement was no longer just about Shandong. It was about dignity, sovereignty, and a new Chinese identity.

By June, the movement had evolved. The students were still leading, but now the working class had taken up the banner. Shanghai became the epicenter of the protests. A massive general strike brought economic life to a standstill. Newspapers, trade associations, and civic groups lent their voices. Even university chancellors called for the release of arrested students. The government, feeling the pressure, dismissed three pro-Japanese officials and ultimately refused to sign the Treaty of Versailles. That refusal marked a significant turning point—it showed that public protest could move the political machinery, at least slightly, in favor of national interest.

The victory was mostly symbolic. Shandong would remain under Japanese control for several more years. But the May Fourth Movement proved something far more powerful: that a coalition of students, intellectuals, workers, and merchants could influence the direction of the nation. That realization would echo through Chinese history for decades to come.

The cultural aftershocks were just as profound as the political ones. The movement accelerated the decline of Confucian values, particularly the patriarchal family structure that had defined Chinese life for centuries. The idea of arranged marriage began to be openly criticized. Women started to appear more prominently in literature, journalism, and activism. Female students marched beside their male counterparts, demanding not just national independence but personal liberation. Foot-binding, once a symbol of feminine virtue, became a symbol of backwardness and oppression.

Intellectuals began publishing in the vernacular, reaching a broader audience than ever before. The phrase “my hand writes what my mouth speaks” became a rallying cry for the new literature. Lu Xun, the great writer of the era, published searing critiques of traditional culture, including the now-famous short story “Diary of a Madman,” which likened Confucian society to a cannibalistic nightmare. A wave of new journals, short stories, plays, and essays flooded the literary scene, giving voice to a modern, secular, and critical generation.

In the wake of the movement, many of the same students and intellectuals began exploring Marxist ideas. Chen Duxiu and Li Dazhao, two of the leading figures of the May Fourth era, would go on to help found the Chinese Communist Party in 1921. They saw in Marxism a path to national strength and social justice. Others, however, saw the movement as a failure of liberalism. They turned away from the West, bitterly disappointed in its hypocrisy. The very idea of Western democracy lost much of its allure in China after Versailles. Even those who did not embrace socialism began to speak of the need for a uniquely Chinese path to modernization.

The Kuomintang, or Nationalist Party, also laid claim to the legacy of May Fourth, though its founder Sun Yat-sen had not been directly involved. Later leaders like Chiang Kai-shek would actually push back against the movement’s anti-traditional bent, reviving Confucian ethics through the New Life Movement. To them, May Fourth had gone too far. They sought a moral regeneration based on discipline, order, and hierarchy.

There were critics from every side. Some believed the movement had been too Western, copying foreign ideas without considering China’s unique traditions. Others believed it had not gone far enough in uprooting those traditions. Still others lamented the urban, elite nature of the movement. Rural China, where the vast majority of people lived, was largely untouched by the protests. The peasants, who would later become central to Mao’s revolution, had little to do with May Fourth.

But even in its contradictions, the May Fourth Movement left an indelible mark. It gave birth to a generation that would shape the future of China—leaders like Zhou Enlai, Mao Zedong, and countless others who had been young students in 1919. It brought the ideas of nationalism, democracy, and social reform into the public square. It proved that the Chinese people could organize themselves not just in opposition to foreign domination, but in pursuit of a better future. That idea—that citizens could demand change through unity and action—became one of the lasting legacies of the movement.

Today, the May Fourth Movement is remembered differently in different places. In mainland China, it is celebrated as the starting point of modern revolution, the seed from which the Communist Party grew. In Taiwan, it is commemorated as a literary and cultural awakening. In the West, it is often overlooked—one of many ripples from the Treaty of Versailles, which had consequences far beyond Europe.

But for the Chinese, it remains a moment of awakening. It was the day students found their voice, the day the streets of Beijing shook with the footsteps of a new generation, the day China stood up not with weapons, but with words. It did not change everything overnight, but it changed the trajectory of a nation.

In a world where diplomacy failed and old powers bartered away the rights of smaller nations, the May Fourth Movement was a refusal to accept silence. It was a declaration that China would no longer be ignored, and that the people themselves would speak for the nation. That spirit of self-determination, born on a spring afternoon in 1919, continues to echo through Chinese history to this day.

Leave a reply to Chen Cancel reply