In early 1917, the Great War had already raged for nearly three years, and Europe was a battlefield of exhaustion and devastation. The United States, despite increasing tensions, had remained neutral, though its sympathies largely lay with the Allies. American industry profited from supplying Britain and France, but the specter of war was looming closer. Germany’s decision to resume unrestricted submarine warfare was the catalyst for what would soon be the most consequential diplomatic blunder of the war. The sinking of American merchant ships by German U-boats provoked outrage, intensifying the debate over intervention, but it was the Zimmermann Telegram that provided the final push towards war by confirming Germany’s hostile intent.

Arthur Zimmermann, Germany’s Foreign Secretary, had devised a plan to counteract the inevitable entry of the United States into the war. His government believed that by offering Mexico an alliance and the prospect of reclaiming Texas, New Mexico, and Arizona, they could create enough instability on the American southern border to distract the United States from sending troops to Europe. The logic was simple—if the Americans were preoccupied with a conflict at home, they would be less of a threat on the Western Front. The telegram, sent on January 16, 1917, instructed Germany’s ambassador in Mexico, Heinrich von Eckardt, to propose this alliance if the United States declared war on Germany. The plan, however, was fatally flawed from the beginning.

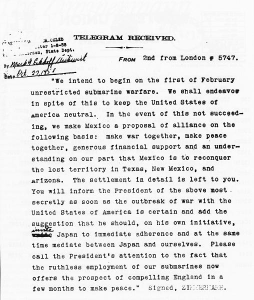

The British, who had intercepted German communications since 1914 by cutting undersea cables, had established a sophisticated cryptographic unit known as Room 40. It was here that British intelligence deciphered the telegram. The challenge was how to use this information without revealing that Britain had cracked Germany’s diplomatic codes, which could compromise future intelligence operations. The British played their hand carefully, feeding the decoded message to the United States while obscuring its true source. On February 24, 1917, the British Foreign Secretary, Arthur Balfour, presented the telegram to the American ambassador in London, Walter Hines Page, who promptly relayed it to President Woodrow Wilson.

For the United States, the telegram was a bombshell. Wilson had been resisting calls for war, but the blatant German attempt to conspire against the United States was too egregious to ignore. On March 1, the press, including major newspapers such as The New York Times and The Washington Post, published the full text of the telegram, and the American public erupted in outrage. Many had been hesitant to enter the war, particularly isolationists and German-Americans, but the idea of Germany plotting with Mexico against the United States turned the tide of opinion. The fact that Zimmermann himself confirmed the authenticity of the telegram only solidified its impact.

Mexico’s response was one of bemusement. President Venustiano Carranza, already dealing with internal instability, instructed his military leaders to assess the feasibility of such an alliance. The conclusion was clear—Mexico was in no position to wage war against the United States. Even if they could seize the promised territories, they could never hold them against American forces. The proposal was dismissed as unrealistic, though it did sour Mexican-American relations, which had already been strained due to the U.S. military’s pursuit of Pancho Villa a year earlier.

Germany had hoped to delay American intervention, but the Zimmermann Telegram had the opposite effect. Wilson, who had campaigned on keeping America out of the war, now had little choice. On April 2, 1917, he went before Congress, calling for a declaration of war to make the world “safe for democracy.” Four days later, the United States formally entered the war against Germany.

Looking back, the Zimmermann Telegram was one of the greatest intelligence coups of the war, comparable to later wartime codebreaking successes such as the British cracking of the Enigma code during World War II. For Britain, it ensured American involvement, which ultimately helped tip the balance in favor of the Allies. For Germany, it was an unmitigated disaster, accelerating the U.S. entry into the war and sealing its fate. For the United States, it was the final push needed to shed its neutrality and commit fully to the fight. In the annals of history, the Zimmermann Telegram stands as a testament to the power of intelligence, the folly of diplomatic miscalculations, and the unpredictable ways in which wars are shaped by the smallest of messages.

Leave a comment