Segment I: Theater Under Occupation

Boston in the winter of 1775 was not yet a story of collapse. It was a story of waiting.

The British Army held the city, and in a narrow military sense, it held it securely. The harbor remained under Royal Navy control. The town’s defenses were intact. Washington’s army sat outside the lines, ill-equipped for a direct assault and unwilling to risk one. There were skirmishes, probes, and constant tension, but no decisive engagement. The war, for the moment, had slowed to a standstill.

That pause proved dangerous.

The winter settled in early and with it came a particular kind of misery. Not the drama of battle, but the grinding monotony of cold days and longer nights. Soldiers drilled, stood watch, and waited. Officers wrote letters, played cards, and waited. The city became a holding pen for men trained for movement and action.

Morale suffered. Boredom crept in alongside discomfort. Isolation from home and uncertainty about the future weighed heavily, especially on the officer class, men accustomed to social life, stimulation, and recognition. Several accounts from the period describe the need for diversion, for something that might help the garrison “forget themselves.”

That phrase appears repeatedly in contemporary descriptions, and it is revealing. Forgetting oneself suggests a conscious escape from circumstances that could not be changed. It is not a solution. It is avoidance.

Out of that impulse emerged an unlikely institution inside an occupied rebel city: organized theater.

British officers formed what they called the Society for Promoting Theatrical Amusements, sometimes referred to informally as Howe’s Strolling Players. It was a corps dramatique drawn from the officer ranks, men who had both the leisure and the inclination to perform. They rehearsed, staged productions, and invited audiences drawn largely from the garrison and loyalist residents.

The enterprise was justified publicly as a charitable endeavor. Proceeds, it was said, would support the widows and orphans of soldiers. That may well have been true in part, but charity alone does not explain the energy devoted to the project. The theater served a more immediate purpose. It gave officers something to do. Something familiar. Something that reminded them of home and normality while the war stalled around them.

The choice of venue mattered.

They selected Faneuil Hall.

This was not merely a large indoor space suitable for performance. It was the symbolic heart of Boston’s political life, a place long associated with resistance to British authority. Patriot meetings, fiery speeches, and protests had filled the hall in the years leading up to open conflict. Now it was converted into an “elegantly fitted” playhouse, complete with stage, seating, and lighting.

The transformation was deliberate. Occupying forces often repurpose significant buildings, but here the symbolism was unmistakable. A hall associated with rebellion was turned into a site of British leisure. It was occupation expressed through culture rather than force.

The productions themselves leaned into that confidence.

Boston’s Puritan heritage had long regarded theater as morally suspect. Plays were seen as frivolous at best and corrupting at worst. The officers knew this and made sport of it. Part of the amusement lay in performing precisely what local custom disapproved.

General John Burgoyne, a man with literary ambitions as well as military rank, played a central role. Burgoyne had experience as a playwright in London and understood the mechanics of the stage. For a performance of The Tragedy of Zara, he wrote a prologue specifically designed to ridicule what he described as Puritan prudery. The language mocked local sensibilities openly, dismissing them as narrow and diseased.

The casting choices amplified the provocation. Roles were played by officers and young women together, a mixing of genders on stage that scandalized some local observers. To British audiences, this was fashionable and refined. To many Bostonians, it was another reminder that the occupying army neither understood nor respected the culture it ruled.

The repertoire included light comedies such as The Citizen, The Apprentice, and The Busy Body, alongside tragedy. These were not obscure selections. They were familiar works, the kind that officers might have seen or performed in Britain. The effect was to recreate, as much as possible, the social world of the metropole within the walls of a besieged city.

Confidence ran through the performances. The officers were not acting like men under threat. They were acting like men convinced that time and power remained on their side.

That confidence found its sharpest expression in a new work written by Burgoyne himself: The Blockade of Boston.

The play was a farce, and its target was unmistakable. American soldiers were portrayed as illiterate and incompetent. Their officers were depicted as empty talkers, capable only of speechifying rather than leadership. The humor rested on caricature and contempt. It reassured its audience that the enemy outside the lines was ridiculous rather than dangerous.

The irony was that the Americans knew about it.

Boston was occupied, but it was not sealed. Civilians moved in and out. Loyalists spoke freely. Information crossed the lines with ease. Washington’s officers were well aware of what was happening inside the city, including the fact that the British garrison had taken to staging plays and that a satirical production aimed at American forces was scheduled for performance.

On the evening of January 8, 1776, Faneuil Hall was filled. The audience had just enjoyed The Busy Body, a light comedy that played well and put everyone in good humor. The atmosphere was relaxed. There was no sense of urgency, no expectation of disruption.

As the curtain was set to rise for The Blockade of Boston, a British sergeant burst onto the stage.

He shouted, “Turn out! Turn out! They’re hard at it, hammer and tongs!”

The audience laughed. They applauded. They assumed the interruption was part of the farce. The timing seemed perfect.

The sergeant shouted again, louder, more urgently. When he insisted that the threat was real, confusion spread. Some still laughed. Others hesitated. Eventually, someone went to the door.

Outside, American forces under Major Thomas Knowlton were carrying out a raid across the frozen ground to Charlestown. The operation was not designed to seize territory or force a decisive engagement. It was designed to exploit distraction. Houses used by the British were set ablaze. Prisoners were taken. Shots echoed in the night.

Inside Faneuil Hall, the illusion collapsed. Women fainted. Officers leapt from the stage area, scrambling for weapons and uniforms. What had been a performance moments earlier dissolved into chaos.

From Cobble Hill, General Israel Putnam observed the British reaction with evident satisfaction. The material damage inflicted by the raid was limited, but its timing delivered the message clearly. The Americans were watching. They were informed. They were capable of choosing the moment of embarrassment.

The night ended without catastrophe, but it left a mark.

The British had not been defeated. They still held Boston. Yet something fundamental had been exposed. Confidence had drifted into complacency. Distraction had replaced attentiveness. Performance had been mistaken for control.

The occupation, for all its outward order, was already beginning to misjudge its situation.

Winter was not finished.

Neither was the war.

Segment II: Cold, Hunger, and the Occupation Eating Itself

Once the illusion of leisure faded, the British Army in Boston confronted a reality that could no longer be mocked or staged away. Winter did not merely inconvenience the occupation. It governed it.

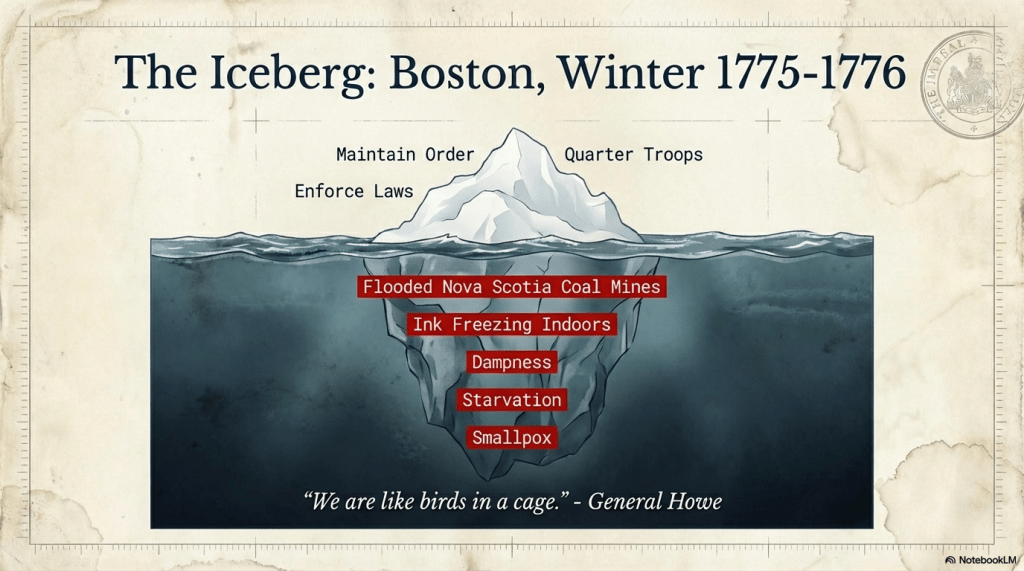

The winter of 1775–1776 was severe even by New England standards. Contemporary accounts described cold so persistent that ink froze inside bottles left near indoor hearths. Writing became difficult not because of indecision, but because the tools themselves failed. Dampness settled into every space. Walls sweated. Clothing never fully dried. Straw bedding absorbed moisture and turned sour beneath sleeping bodies.

Boston had roofs, but it did not have shelter in the military sense. The city had not been built to house thousands of soldiers through a prolonged winter. Churches, warehouses, taverns, and private homes were pressed into service, none designed for the sustained heat and sanitation such numbers required. Chimneys smoked poorly. Fires warmed unevenly. Crowding was unavoidable, and with it came illness.

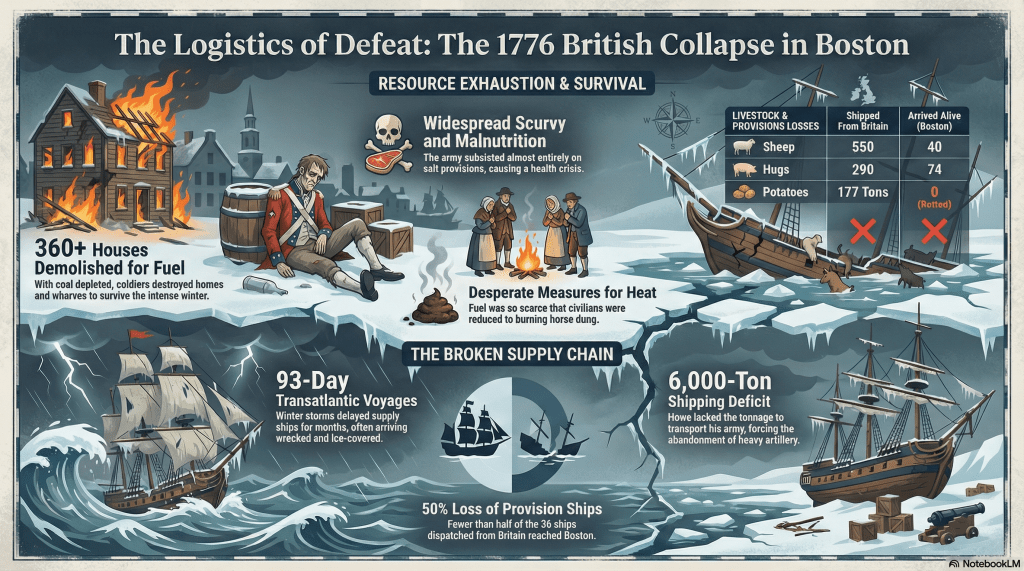

Cold was uncomfortable. Fuel scarcity was dangerous.

General William Howe reported at one point that the garrison had only three weeks of fuel remaining. That figure dominated every calculation. Fires were not a luxury. They were essential to maintaining basic function. Weapons had to be kept dry. Men had to retain dexterity. Sickness had to be slowed if not prevented. Without heat, the occupation could not hold.

The scale of consumption was immense. The garrison burned hundreds of tons of coal each week. Under ordinary circumstances, Britain’s imperial supply system could have sustained that demand. These were not ordinary circumstances.

Coal mines in Nova Scotia were flooded. Winter storms delayed shipping. Rebel privateers intercepted supply vessels before they reached port. What had once been a reliable flow became erratic, then uncertain, then insufficient. Each missed delivery narrowed the margin between endurance and collapse.

As fuel supplies dwindled, the city itself became the reserve.

At first, destruction was incremental. Spare lumber disappeared. Fence rails were pulled up. Outbuildings were dismantled quietly. Then the practice expanded. Wharves were stripped of planking. Long sections of fencing collapsed. Entire houses were pulled apart beam by beam, their wood fed into stoves and fireplaces.

More than three hundred sixty structures were demolished for firewood alone.

This was not random vandalism. It was methodical survival. But survival does not respect discipline. Soldiers scavenged without orders. Units acted independently. Howe eventually threatened execution for unauthorized destruction, a measure that revealed the depth of the crisis. When a commander must threaten death to stop his men from dismantling the city they occupy, control has already weakened.

Civilians were drawn into the same desperation. With conventional fuel exhausted, many residents resorted to burning horse dung for heat. The practice was foul and inefficient, but it burned. It became a marker of how far the city had fallen under the pressure of occupation and winter combined.

Even spaces once regarded as untouchable were consumed.

The Old South Meeting House, long a center of civic and religious life, was gutted. Pews were torn out and burned. The interior floor was cleared and repurposed as a riding ring for dragoons. Horses circled where sermons and public debate had once taken place. This was not a symbolic act in the theatrical sense. It was necessity asserting itself without sentiment.

Cold eroded comfort. Hunger eroded cohesion.

By midwinter, the British garrison subsisted almost entirely on salt provisions. Salt beef and salt pork dominated the diet. Fresh food was scarce. Vegetables were rarer still. The consequences were predictable. Scurvy spread through the ranks. Gums softened. Teeth loosened. Wounds healed slowly. Illness became routine rather than exceptional.

Commissary reports reflected the strain. By mid-January, flour supplies were measured in weeks, not months. Peas were gone entirely. Butter and rice were minimal. The small dietary variations that sustained morale had vanished. The garrison lived on monotony, and monotony undermined health.

More troubling was the diversion of hospital supplies. Meat intended for the sick often failed to reach them, taken instead by men whose hunger overrode regulation. This was not cruelty. It was erosion. Hunger reshaped priorities and weakened discipline in ways that punishment alone could not correct.

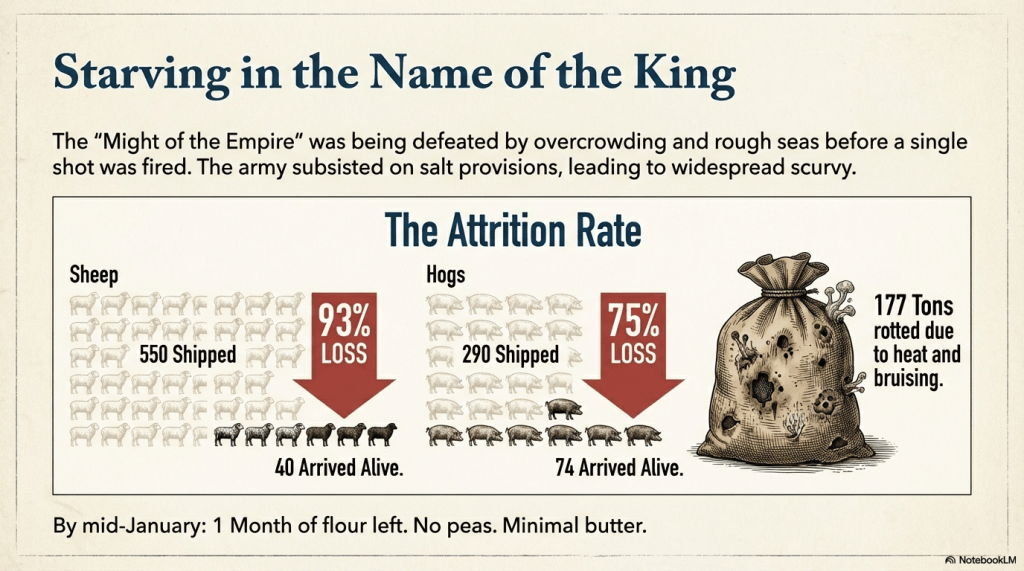

Britain attempted to address the crisis through shipment rather than reform. Fresh livestock was loaded onto transports and sent across the Atlantic. The plan appeared sound on paper. It failed at sea.

Voyages were rough. Ships were overcrowded. Animals died in staggering numbers before reaching shore. Of more than five hundred sheep shipped, only a few dozen survived the crossing. Of nearly three hundred hogs, fewer than a third arrived alive. Disease, stress, and overcrowding claimed the rest.

Vegetables fared no better. Large quantities of potatoes were shipped only to rot during transit. Bruising, heat, and poor storage turned them into waste before they could be consumed. The Atlantic proved an unforgiving barrier to perishable abundance.

By this point, the British occupation of Boston had lost its strategic rhythm. The army remained capable, but it was no longer operating from a position of choice. Decisions were driven by necessity rather than initiative. Each day was spent managing shortages rather than shaping outcomes.

Boston itself was being consumed to sustain the garrison. Infrastructure became fuel. Homes became shelter for soldiers who dismantled other homes to stay warm. Civic spaces lost their meaning under the pressure of survival. The city was no longer a prize to be held. It was a resource being stripped to keep the occupation alive.

Outside the lines, the Americans did not rush to exploit the situation with frontal assault. They did not need to. Time was doing the work. Each week of winter deepened British dependence on fragile supply chains. Each act of demolition hardened civilian resentment. Each illness thinned effective manpower.

The occupation had not collapsed. But it had begun to hollow itself out.

The British Army entered Boston assuming permanence and superiority. Winter exposed the limits of both. Power required supply. Occupation requires sustainability. Neither could be assumed indefinitely under siege, cold, and scarcity.

By the time the season began to loosen its grip, the question was no longer how Britain would break the stalemate.

It was how long the occupation could endure before endurance itself became impossible.

Segment III: The Sea Closes, the Cage Shuts

By the time winter began to loosen its grip on Boston, the British Army faced a problem that could no longer be addressed inside the city. The occupation had become dependent on something it could not control.

The sea.

For the British Empire, the Atlantic Ocean was supposed to erase distance. It was the artery through which power flowed, connecting ministers in London to commanders in America and turning scattered colonies into governable space. As long as ships arrived on schedule, authority could be projected with confidence. When that system faltered, everything else followed.

Winter exposed the fragility of that assumption.

Storms battered the North Atlantic with relentless regularity. Ships sailed from British ports under orders that assumed predictable transit times and dependable arrival. Instead, they vanished into weeks of heavy weather. Voyages stretched far beyond expectation. Rigging froze solid. Hulls iced over. Crews arrived exhausted or diminished, if they arrived at all. Each delayed ship widened the gap between what London believed was happening in Boston and what Boston was actually experiencing.

The frigate Orpheus illustrated the problem with stark clarity. She required ninety-three days to reach Halifax, a journey that under normal conditions should have taken a fraction of that time. When she finally limped into port, she was coated in ice, her rigging damaged, her hull battered by storms. She brought no reassurance. She brought evidence.

And she was not alone.

In late 1775, Britain dispatched thirty-six provision ships toward North America. Fewer than half reached Boston. Some were captured. Some were driven off course. Others disappeared without explanation, leaving no wreckage, no confirmation, and no certainty. Each missing vessel represented more than lost cargo. It represented a collapse in information.

This absence of feedback proved corrosive. In London, administrators could no longer distinguish between delay and loss. Replacement shipments were discussed before original cargoes were confirmed missing. Orders were issued, revised, and contradicted. Authority flowed outward across the Atlantic, but reliable knowledge did not return in time to matter.

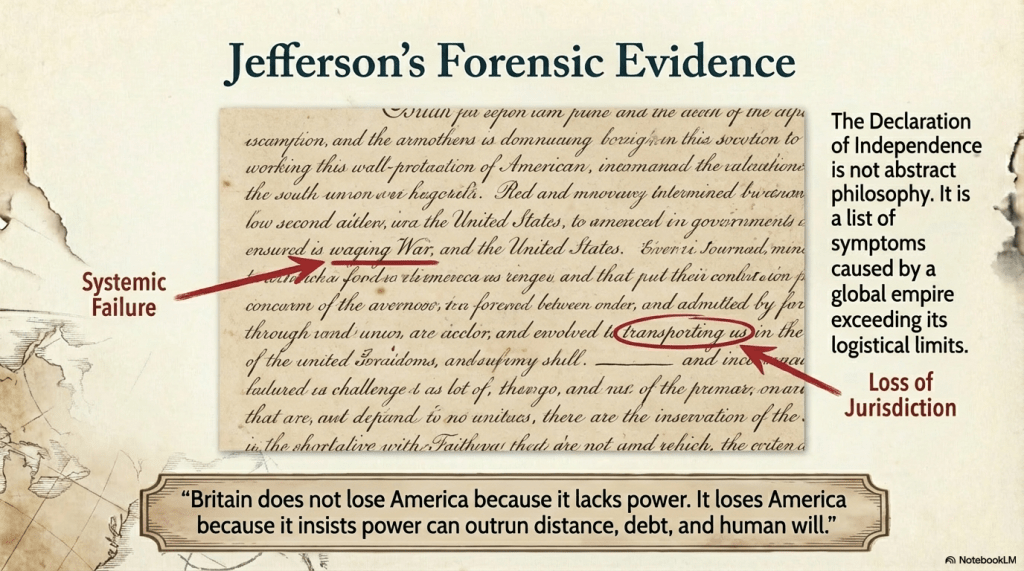

Thomas Jefferson would later describe this condition precisely in the Declaration of Independence. Grievances such as the obstruction of justice, the rendering of the military independent of civil authority, and the transportation of Americans overseas for trial were not abstract ideological complaints. They were observations of what happens when governance attempts to operate beyond the limits of communication and logistics.

When instruction arrives months late, commanders improvise. When civil authority cannot function at distance, military authority fills the vacuum. What Jefferson framed as tyranny often emerged from administrative blindness rather than deliberate design.

Boston was living proof.

General William Howe could not launch a winter offensive. The condition of his army, the uncertainty of supply, and the unreliability of communication made movement dangerous. At the same time, he could not meaningfully withdraw. The army depended on the city’s remaining shelter and resources. Any premature movement risked exposure and collapse.

Howe described his army as sitting “like birds in a cage.”

The image was exact. The cage was not constructed solely by American fortifications. It was built from distance, weather, and silence. The army remained intact and disciplined, yet immobilized by its own needs. Every option carried unacceptable risk.

The Americans did not attempt to break that cage by force. They understood they did not need to. Instead, they focused on tightening it.

Washington’s so-called Mosquito Fleet did not challenge the Royal Navy in open battle. It did not seek decisive naval engagements. It harassed. It delayed. It disrupted. Privateers and small vessels targeted transports rather than warships, understanding that an army deprived of supplies and information could be neutralized without confrontation.

This approach aligned directly with Jefferson’s grievance that Britain had “cut off our trade with all parts of the world.” To the colonists, this was not metaphor. It was lived experience. Normal commerce collapsed. Supply lines faltered. Economic life stalled. What Britain viewed as enforcement appeared in America as suffocation.

The capture of the ordnance brig Nancy brought the lesson home. Her cargo of two thousand muskets and thirty tons of shot transformed American scarcity into adequacy. Arms that had been hoarded could now be issued. Ammunition could be expended rather than conserved.

For Britain, the loss struck deeper than the numbers suggested.

The British Admiralty referred to the capture as a “fatal event.” Not fatal in the sense of immediate defeat, but fatal in the structural sense. Those arms would not be replaced quickly. That ammunition would not arrive by decree. The loss confirmed what winter and storms had already revealed. The Atlantic could not be commanded at will.

Jefferson’s grievance that Britain was “transporting us beyond seas to be tried for pretended offences” reflected the same systemic breakdown. London no longer trusted colonial institutions to function as extensions of its authority. Distance eroded confidence. When governance cannot rely on local systems, it substitutes coercion. When coercion fails, paralysis follows.

By early March, Howe confronted a reality he could no longer postpone. Remaining in Boston offered no path forward. The city consumed resources without producing advantage. Supplies were too uncertain. Communication too slow. The army’s condition too fragile.

Yet leaving posed its own problem.

Britain lacked sufficient shipping to evacuate the army and loyalist civilians in one movement. Howe calculated that twenty-eight thousand tons were required. Only twenty-two thousand were available. The deficit forced choices that exposed the true cost of isolation.

Heavy artillery was abandoned, including massive mortars that had once symbolized British dominance. Wagons were left behind. Horses could not be transported in sufficient numbers. Loyalists were prioritized selectively, often according to space rather than loyalty. Many who had cast their future with the Crown were left behind to face uncertain consequences.

This was not retreat as strategy. It was retreat as admission.

Even then, the army could not proceed directly to New York. Men were weakened. Transports were overcrowded. Supplies were insufficient for immediate redeployment. Instead, the force withdrew to Halifax, not to seize initiative, but to recover. Halifax represented pause, not progress. It was a place to restore supply lines, reestablish communication, and regain administrative coherence.

Boston was abandoned not because it had fallen, but because it could no longer be held at acceptable cost.

That distinction mattered.

The British Army left intact, but altered. The occupation had demonstrated that imperial power depended not merely on force, but on systems vulnerable to disruption. Distance magnified every weakness. Winter accelerated every delay. An enemy who understood logistics could bleed an empire without decisive battle.

For Jefferson, Boston provided evidence. The grievances listed in the Declaration were not philosophical abstractions. They were drawn from observation. They described what happens when governance attempts to operate beyond the limits of communication, supply, and time.

The war did not end at Boston. But it changed there.

Empires rarely collapse all at once. More often, they stall. They hesitate. They guess. And eventually, they withdraw, not in defeat, but in recognition that power exercised at distance is always conditional.

The sea had stopped answering.

And when it did, the cage finally shut.

Much of today’s lesson was drawn from Rick Atkinson’s “The British Are Coming,” particularly Chapter 9.

I cannot recommend this book highly enough. If you don’t want to read it, get the Audible version. It is well written, well read, and it will open your eyes to more than the basic ideas of the Revolution.

Leave a comment