Thomas Paine entered the world quietly, which is often how trouble begins. He was born on January 29, 1737, in the small market town of Thetford in Norfolk, a place better known for routine than rebellion. His father, Joseph Paine, was a Quaker stay maker, sewing corsets and living by a creed that distrusted hierarchy and ceremony. His mother, Frances, was Anglican, tied to the established church and its rhythms. That combination mattered. Paine grew up inside a religious household that never fully agreed with itself, where obedience and skepticism shared the same roof. It left him with an early suspicion of authority that claimed sacred sanction, and a habit of asking why things were done simply because they always had been.

His education was brief and practical. By around thirteen, formal schooling was finished, and Paine was apprenticed to his father. Stay making was skilled work, but it was also confining. It taught him discipline and precision, but it offered little sense of advancement. Paine learned early that honest labor did not necessarily lead to security or respect. The trade anchored him to the realities of working life, the long hours, the thin margins, the quiet vulnerability to forces beyond one’s control. It also gave him his first education in the frustrations of ordinary people, a perspective that would later shape his writing far more than any book learning.

Restlessness arrived early. At nineteen, Paine ran off to sea, serving briefly as a privateer aboard the King of Prussia. The experience was short and unglamorous. Privateering promised adventure and profit, but delivered danger and disorder. Paine returned to land without wealth or distinction, but with a sharper sense of how empires operated from below deck. Authority at sea was blunt and absolute, and survival depended less on noble ideals than on endurance and luck. It was a lesson he would revisit often.

The next decade and more read like a catalog of near successes and quiet failures. Paine drifted between professions, returning to stay making, trying his hand at teaching, and eventually securing a position as an excise officer, collecting taxes on behalf of the Crown. The job placed him in an unenviable position. He was an agent of government enforcement, but he lived among the people most burdened by that enforcement. He saw firsthand how policy written in London landed unevenly on real lives. It was steady work, but it never fit him well.

His personal life offered little stability. His first wife, Mary Lambert, died in childbirth within a year of their marriage. The loss was devastating and left Paine emotionally and financially adrift. His second marriage, to Elizabeth Ollive, ended more slowly and no less painfully. Their attempt at running a small tobacco business collapsed, leaving debts, separation, and another reminder that effort did not guarantee reward. By his mid thirties, Paine had accumulated more disappointment than success, and he was increasingly unwilling to accept that failure was simply his own fault.

It was in Lewes, while working as an excise officer, that Paine’s political consciousness sharpened into action. He joined a debating society, read widely, and began to see patterns behind his personal struggles. In 1772, he put his frustrations into print with The Case of the Officers of Excise, a pamphlet arguing that tax collectors deserved fair pay. It was not a revolutionary document, but it was bold. Paine appealed to reason, justice, and economic reality, rather than tradition or deference. The government response was swift and predictable. He was dismissed from his post. Speaking plainly about systemic unfairness, he learned, was rarely rewarded by the system in question.

By 1774, Paine was broke and facing the prospect of debtor’s prison. England had offered him work, loss, and instruction, but little hope. It was at this moment that he crossed paths with Benjamin Franklin in London. Franklin recognized something valuable in Paine, a clarity of thought and an ability to communicate complex ideas without pretense. He offered practical help, a letter of introduction, and advice that would change Paine’s life. Go to America. There was room there, Franklin suggested, for a man who could think and write as Paine did.

The journey nearly killed him. When Paine arrived in Philadelphia in November 1774, he was gravely ill with typhus. He had to be carried off the ship and nursed back to health. It was an inauspicious beginning, but America had a way of forgiving weak starts. The colonies were restless, argumentative, and increasingly suspicious of distant authority. Paine recovered quickly, found work, and almost immediately began to make himself useful.

Within months, he was editing the Pennsylvania Magazine, published by Robert Aitken. Under Paine’s direction, circulation rose sharply. He filled its pages with essays, commentary, and poetry that spoke directly to readers rather than over them. He wrote about politics, society, and morality in a language that assumed intelligence without requiring refinement. This was not accidental. Paine believed that important ideas should be accessible to those who bore their consequences.

It was in these pages that his early radicalism emerged clearly. He published an essay condemning slavery, African Slavery in America, at a time when many colonists preferred not to examine the contradiction between liberty and human bondage. He argued against the institution in moral terms, but also in practical ones, challenging readers to confront the cost of their assumptions. He also advocated for women’s education and dignity, pushing against cultural boundaries that most accepted without question. These positions did not make him universally popular, but they established his voice. Paine was not interested in polite reform. He was interested in coherence, in aligning professed values with lived realities.

By late 1775, the colonies were moving toward open conflict with Britain, but independence was still an unsettled idea. Many hoped for reconciliation, or at least a return to an earlier balance. Paine watched this hesitation with growing impatience. He had lived under British authority long enough to distrust its willingness to reform itself. He understood, from experience, how power responded to reasoned appeals when those appeals threatened its comfort.

This understanding would soon find expression, but even before Common Sense, Paine had already begun reshaping colonial discourse. He framed political questions in moral language without invoking divine sanction. He appealed to everyday experience rather than legal precedent. He treated ordinary readers as capable of judgment. That approach, rooted in his own hard lessons, was his true innovation.

By the start of 1776, Thomas Paine was no longer simply an English immigrant finding his footing in America. He was a writer with a following, a thinker sharpened by disappointment, and a man who had learned, painfully, that systems rarely change themselves. His radicalism was not born in salons or universities. It was forged in workshops, sickbeds, failed marriages, and unpaid wages. When he finally spoke to the colonies about independence, he would do so as someone who had already lived with the consequences of distant authority and found them wanting.

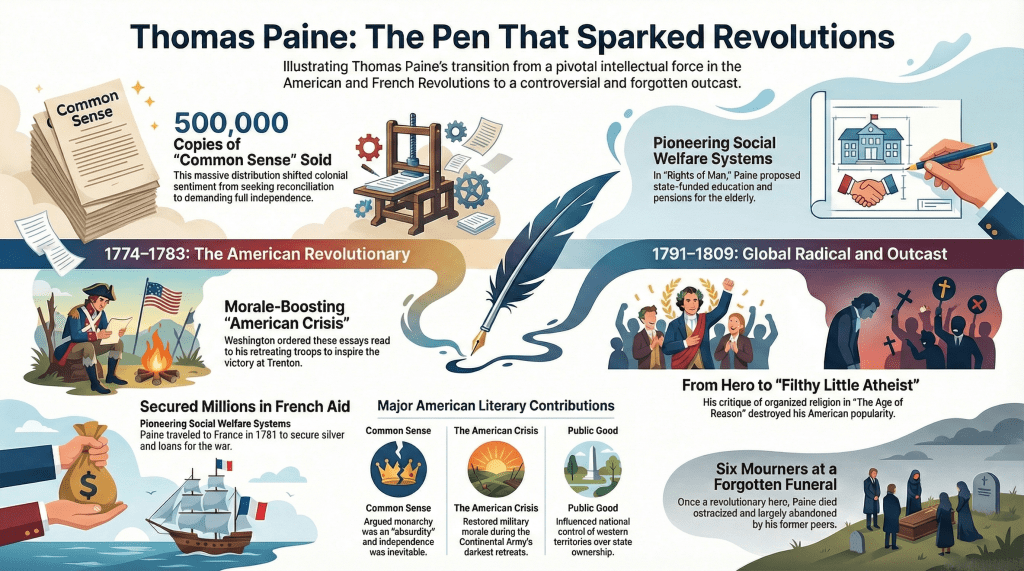

By the opening days of 1776, the question in the colonies was no longer whether something had gone wrong. It was whether anyone was willing to say out loud that the relationship itself was broken. Thomas Paine said it without apology. Common Sense appeared anonymously in January, cheaply printed and aggressively direct, with none of the careful hedging that had characterized so much colonial political writing. Paine did not ask readers to admire his learning. He asked them to look at their own lives and answer a simple question. What possible benefit justified continued submission to a distant crown that ruled by accident of birth and enforced its will by bayonet and decree.

Paine attacked monarchy not as a temporary abuse but as a permanent absurdity. He stripped it of romance and tradition, calling George III the “Royal Brute of Britain,” a phrase that shocked polite society precisely because it was so unpolite. This was not the language of petitions or appeals to ancient rights. It was the language of a man pushing furniture aside so the room could finally be examined. Paine argued that independence was not a dangerous gamble but an overdue correction, that reconciliation was neither likely nor desirable, and that continued attachment to Britain guaranteed future conflict rather than stability.

What made Common Sense explosive was not simply its argument, but its audience. Paine wrote for artisans, farmers, laborers, and shopkeepers, people who had never been asked to weigh the legitimacy of monarchy but who paid its costs daily. He used biblical cadence without biblical submission, moral reasoning without clerical permission. He trusted readers to follow him, and they did. Estimates of circulation vary, but even conservative numbers are staggering for the period. Copies were passed hand to hand, read aloud in taverns and workshops, argued over in churches and marketplaces. Independence stopped sounding like the obsession of radicals and began to sound like the conclusion any reasonable person might reach.

The pamphlet did not cause the Revolution, but it accelerated it, hardening opinion and clarifying stakes. Those who still hoped for reconciliation suddenly had to explain why submission made sense. Leaders who had hesitated found themselves pushed by public sentiment they could no longer ignore. Paine had not merely joined the revolutionary conversation. He had changed its vocabulary.

When fighting intensified, Paine refused the safety of distance. He followed the Continental Army during its worst months, sharing its exhaustion and its uncertainty. By late 1776, the rebellion appeared close to collapse. British forces had driven Washington’s army across New Jersey, enlistments were expiring, supplies were scarce, and desertion loomed. It was during this retreat that Paine wrote the first number of The American Crisis.

Its opening line did not flatter the reader. “These are the times that try men’s souls.” Paine contrasted perseverance with convenience, commitment with comfort, and called out the “summer soldier and the sunshine patriot” who vanished when the work turned dangerous. The essay did not promise easy victory or divine intervention. It promised meaning in endurance. Washington understood its value and ordered it read to the troops before the crossing of the Delaware and the attack on Trenton. Words alone did not win the battle, but they steadied men who were deciding whether to remain soldiers or return home.

Paine continued to write Crisis essays throughout the war, each one responding to events as they unfolded. He mocked British proclamations, challenged complacency among Americans, and refused to let victory become an excuse for forgetfulness. He insisted that independence meant responsibility, not merely separation. Liberty, he reminded readers, was not self sustaining. It required attention and sacrifice, even after the cannons fell silent.

Alongside his writing, Paine entered the unglamorous machinery of government. He accepted a position as secretary to the Committee for Foreign Affairs, a role that demanded organization, discretion, and patience. It was not well suited to him. Paine had little tolerance for secrecy when it masked self interest, and even less for officials who profited from confusion. This tension came to a head in the affair involving Silas Deane, an American diplomat accused of corruption and war profiteering.

Believing the public interest demanded transparency, Paine published information that revealed secret negotiations and financial arrangements with France. His intention was to expose misconduct, but the effect was diplomatic embarrassment. France was still a covert ally, and Paine’s disclosures complicated relations at a critical moment. Congress forced him to resign in 1779. Once again, Paine discovered that honesty could be unwelcome even in a revolution dedicated to truth. His dismissal was framed as a matter of prudence, but it reflected a deeper discomfort with a man who refused to separate principle from practice.

Paine did not retreat into bitterness. Instead, he turned his attention to structural questions about the nation taking shape. In Public Good, published in 1780, he argued that western lands should belong to the national government rather than individual states. He believed that a shared public domain would strengthen the union, prevent land speculation from undermining republican equality, and provide resources for common purposes. These ideas would later influence the framework of the Northwest Ordinance, shaping American expansion in ways Paine could not fully foresee, but clearly intended to guide.

Financial necessity soon drew Paine back into active service. In 1781, with the war dragging on and American finances in crisis, he accompanied John Laurens to France on a desperate mission to secure aid. The stakes were high and the margins thin. The success of the mission depended not only on diplomacy, but on trust. Paine’s reputation as an uncompromising advocate for the American cause helped persuade French officials that their investment was worthwhile. The result was substantial. The mission returned with millions of livres in silver and a significant loan, funds that allowed the Continental Army to continue operations at a moment when collapse was a real possibility.

Throughout these years, Paine lived precariously. He donated the proceeds from Common Sense to support the army, purchasing supplies, including mittens for soldiers enduring winter campaigns. He accepted no pension and accumulated no fortune. His commitment to the cause was practical rather than symbolic. He believed that independence required more than speeches and signatures. It required cold hands to be warmed and empty stomachs to be fed.

As the war drew toward its conclusion, Paine remained restless and unsatisfied. Victory did not erase his concerns about inequality, corruption, or the fragility of republican government. He had seen how quickly ideals could be compromised by convenience, and how easily personal ambition could disguise itself as public service. He admired Washington’s restraint but distrusted hero worship. He celebrated independence but refused to pretend it solved everything.

By 1783, Paine stood at an odd intersection. He was widely recognized as a central voice of the Revolution, yet he held no secure place within its emerging power structure. His influence came from words rather than office, from persuasion rather than command. He had helped shift a continent’s thinking, sustained an army’s morale, and shaped early debates about national purpose. He had also offended allies, embarrassed governments, and refused to learn the useful art of silence.

This tension was not accidental. Paine believed revolutions failed not because their ideals were too bold, but because their participants grew tired of living up to them. He had little interest in becoming comfortable once the fighting stopped. The habits that had made him indispensable during crisis made him inconvenient afterward. The skills that ignited rebellion did not translate easily into peacetime harmony.

Still, the record of these years is clear. Paine did not merely write about independence. He lived inside its uncertainties, shared its dangers, and argued relentlessly for its coherence. He understood that a nation born in resistance would always be tempted by ease once the pressure lifted. His work during the war years stands as a reminder that revolutions are not sustained by slogans alone, but by constant attention to the distance between what is said and what is done.

The war would end. The arguments would not. Paine knew that, even if many preferred to forget it.

When the fighting ended and the banners were folded away, Paine did what he had always done when a moment settled into comfort. He left. Victory did not hold him. Stability never had. In 1787 he returned to Europe, carrying with him the confidence of someone who had helped midwife a republic and the unease of someone who suspected that its lessons had not been fully learned. He arrived in a Britain watching events in France with fascination and dread, and within a few years he found himself once again at the center of an argument larger than his own safety.

Edmund Burke’s Reflections on the Revolution in France struck Paine as a betrayal of reason. Burke defended tradition, hierarchy, and inherited authority with eloquence and fear, warning that the French experiment would end in chaos. Paine answered not with nostalgia but with principle. Rights of Man, published in 1791 and expanded the following year, was a defense of revolution as a moral necessity rather than a reckless indulgence. Paine rejected hereditary government outright. No generation, he argued, had the right to bind the next. Authority that could not justify itself to the living had no legitimate claim at all.

He went further. Paine sketched a vision of society in which government existed not to preserve privilege but to secure dignity. He proposed public education, support for the poor, and pensions for the elderly, not as charity but as a return of value taken by the state over a lifetime. These ideas unsettled Britain more than his earlier American arguments ever had. Independence across an ocean was one thing. Structural reform at home was another.

The government responded predictably. Paine was charged with seditious libel. The verdict was a formality. Before the warrant could be served, he fled to France, leaving behind a country that had little patience left for his brand of clarity. In his absence, he was tried and convicted. The sentence mattered less than the message. He was no longer a tolerated nuisance. He was an outlaw.

France welcomed him with enthusiasm that bordered on fantasy. Despite speaking no French, Paine was elected to the National Convention, a testament to his reputation rather than his practicality. He took his seat among men who believed history itself had granted them absolution. Paine believed in revolution, but he believed it had limits. This difference soon placed him in danger.

When the question of Louis XVI’s fate came before the Convention, Paine argued against execution. He had no affection for monarchy, but he understood the power of precedent. Killing a captive king, he warned, would turn revolution into vengeance and teach future rulers to fear surrender more than resistance. He proposed exile, even suggesting that the former king be sent to America. It was a humane argument, and a fatal one. The Jacobins were in no mood for restraint. Paine’s opposition marked him as suspect, insufficiently pure, dangerously moderate.

The Revolution devoured its own with mechanical efficiency. Paine was arrested and imprisoned in Luxembourg Prison during the Reign of Terror. The charges were vague, which was typical. Guilt no longer required specificity. While confined, he watched prisoners taken daily to the guillotine, the machinery of justice reduced to a schedule. His survival came down to an accident. A guard marked his cell door with chalk, indicating execution, but did so while the door stood open. When the doors were later closed, the mark faced inward. The executioners passed him by. Paine lived because of a hinge and a moment’s inattention.

During imprisonment and in the years that followed, Paine turned his attention to religion, or more precisely, to authority claimed in its name. The Age of Reason was written partly in confinement and completed after his release. Paine did not argue against belief in God. He argued against institutions that demanded submission while forbidding inquiry. He embraced Deism, insisting that reason and observation were more reliable guides to truth than inherited doctrine. He attacked the Bible’s infallibility with the same bluntness he had once reserved for monarchy.

The response was swift and unforgiving. In Europe, the book added to his reputation as a dangerous thinker. In the United States, it destroyed what remained of his standing. The country that had embraced his call for independence recoiled from his religious skepticism. Churches denounced him. Former allies fell silent. Paine had underestimated the durability of faith as a social bond, and overestimated the willingness of the victorious to tolerate dissent once their own legitimacy felt secure.

Still, he continued to think about justice in practical terms. Agrarian Justice, published in 1797, addressed the problem of inequality not through rhetoric but through structure. Paine argued that private land ownership deprived others of a shared natural inheritance. To correct this, he proposed a tax on inherited land to fund payments to young adults and pensions for the elderly. It was not socialism, and it was not charity. It was restitution. The proposal anticipated systems that would emerge more than a century later, and like many ideas ahead of their time, it was treated as both naive and dangerous.

Paine’s personal bitterness deepened alongside his isolation. He believed that George Washington, whom he had once admired, had abandoned him during his imprisonment in France. In 1796, he published an open letter accusing Washington of treachery and incompetence. It was a miscalculation born of hurt rather than strategy. The letter confirmed for many that Paine had become reckless, unable or unwilling to distinguish between principle and grievance. It severed one of the last bridges back to public favor.

When he returned to the United States in 1802 at the invitation of Thomas Jefferson, he found a colder country than the one he had left. Federalists regarded him as a dangerous radical. Religious communities dismissed him as an atheist. He struggled financially and socially, moving between lodgings, dependent on a shrinking circle of friends. He was mocked in print and ignored in public. The man who had once helped give voice to a nation found himself treated as an embarrassment.

Paine died in New York City in 1809. Only six people attended his funeral. No official mourning. No procession. The silence was deliberate. America had moved on, or believed it had. Paine’s refusal to soften his edges made him easier to forget than to reconcile.

Even death did not grant him rest. A decade later, William Cobbett, a radical journalist and admirer, exhumed Paine’s body from his farm in New Rochelle. Cobbett intended to return the remains to England for a proper memorial, believing that Britain might finally recognize the man it had cast out. The plan collapsed. Cobbett died, and Paine’s bones were dispersed, sold, lost, or claimed by collectors and opportunists. Stories circulated of skulls and jawbones, none verified, all improbable. The physical remains of Thomas Paine vanished into rumor.

There is a fitting cruelty in that ending. Paine spent his life dismantling false reverence, insisting that ideas mattered more than symbols, and that authority should never rest on relics. In the end, he left no grave to sanctify, no monument to soften his contradictions. What remains are the words, still sharp, still unsettling, still resistant to comfortable placement.

Paine did not belong to any one nation or movement by the end. He belonged to the argument itself. He believed that reason demanded renewal, that revolutions failed when they stopped asking hard questions, and that gratitude was a poor substitute for accountability. His life after victory reminds us that founding voices are often least welcome once the foundations are poured. He understood that cost. He paid it without apology, and without retreat.

Leave a comment