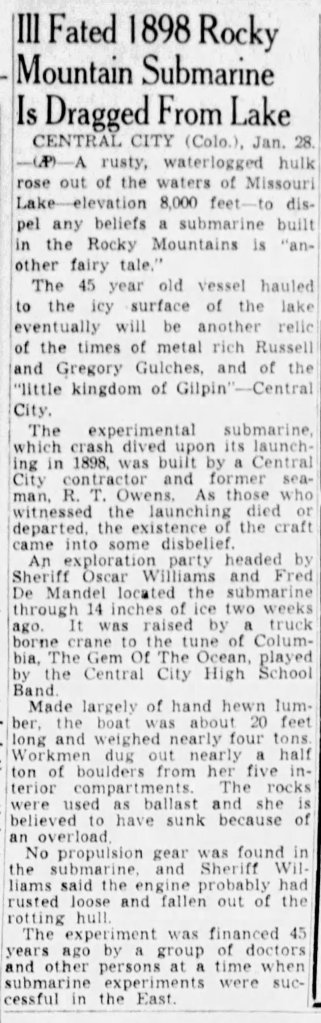

In January 1944, while the world was busy measuring progress in terms of island chains and casualty lists, a smaller crowd gathered at Missouri Lake outside Central City, Colorado. The lake was frozen hard, the kind of cold that cracks knuckles and tempers alike. Men with ropes and a truck crane stood on the ice, chopping through it in careful sections. When the winch finally took hold and the object broke free from forty five years of mud and silence, it did not look like progress. It looked like a joke that had waited patiently for its punchline. A rusty, waterlogged hulk, cigar shaped and stubborn, rose out of the lake at nearly nine thousand feet above sea level, more than a thousand miles from the nearest ocean. The local high school band struck up “Columbia, the Gem of the Ocean,” because of course they did. If history has a sense of humor, this was one of its quieter laughs .

The newspapers called it the Rocky Mountain submarine, sometimes the Nautilus, sometimes simply the mountain sub. One wire service report described it as dispelling any remaining belief that a submarine in the Rockies was another fairy tale, which tells you how long the story had been floating around without ever quite surfacing . Locals had joked for years about the longest crash dive in history, a vessel that went straight down on its maiden voyage and never came back up. Now it was there in plain sight, hauled onto the ice with its ballast rocks still rattling inside, stubborn evidence that someone, once, had meant this thing to work.

To understand how a submarine ended up at the bottom of a frozen mountain lake, you have to step backward past the jokes and into the particular restlessness of the late nineteenth century. Central City in the 1890s was no sleepy mining camp. It had already burned through its first boom and survived it. The richest square mile on earth had produced fortunes and funerals in equal measure. Engineers were respected here, especially the kind who could make water flow where it stubbornly refused to go and make mines stand up a little longer than they had any right to.

Rufus T. Owens fit that world. He was known locally as a skillful engineer and a peculiar man, which in a mining district was almost a job requirement. He designed municipal water systems for Central City and Black Hawk, practical work that kept people alive and businesses running. He designed mine buildings and understood the pressures of confined spaces, both physical and mental. He was also, by most accounts, a recluse, a man who preferred sheds and drawings to saloons and applause. That detail matters, because what he attempted next was not the sort of thing you unveiled with a brass band.

The timing was not accidental. The Spanish American War was unfolding, and with it came a brief but intense submarine craze. Newspapers were full of speculation about undersea warfare, coastal defense, and secret weapons. The United States Navy was holding design competitions, and inventors like John Holland were proving that submarines were no longer the stuff of fantasy. Jules Verne’s Nautilus had already lodged itself firmly in the public imagination. If you were an engineer with ambition and a slightly bent sense of possibility, it was hard not to wonder if you could do something similar, even if you lived in the high Rockies.

Owens built his submarine in secret, inside a shed near Central City. The secrecy was partly practical and partly human. New ideas draw laughter faster than they draw funding, especially when those ideas involve putting a submarine into a mountain lake. By the time the craft was finished in the summer of 1898, it was about twenty feet long, roughly five feet high, and three and a half feet wide. The hull was made largely of hand hewn timber, wrapped in what contemporaries described as a theoretically watertight skin of soldered metal sheets. The word theoretically does a lot of work there. Five foot iron rods protruded from the sides for reasons that remain unclear. When the vessel was recovered decades later, there was no obvious propulsion or steering gear, which has fueled debate ever since about whether it was unfinished or simply a proof of concept for buoyancy and ballast .

Missouri Lake was chosen for the test, a cold private body of water north of town. Owens intended to captain the submarine himself, which suggests either confidence or fatalism, possibly both. Friends convinced him to test it unmanned first, a decision that almost certainly saved his life. To simulate a crew, they loaded the interior with rock. Estimates vary wildly, from fifteen hundred pounds to several tons, which tells you something about how carefully this experiment was documented. What is consistent is that the ballast was unbalanced. When the Nautilus was launched, it tipped, took a gulp of water through the open hatch, and sank straight down to the bottom. There was no dramatic struggle, no heroic near miss. It simply vanished into the cold dark, as final and quiet as a bad idea realized too late.

There was no practical way to retrieve it. Missouri Lake froze solid, and the technology to raise a heavy object from its depths did not exist locally. Owens abandoned the project and eventually moved to Pueblo, where he died in 1919. The submarine stayed where it was, slowly turning from experiment to rumor. Over the years it became a saloon story, something old timers swore they had seen or heard about, usually after a drink or two. Some people believed it. Many did not.

In 1932, the legend nearly ended. The Chain O’ Mines company drained part of the lake for mining operations, briefly exposing the hull. This should have settled the matter, but instead it added a new chapter of frustration. Before anyone could do much with the discovery, souvenir hunters removed the hatch. Then the water returned, and the submarine slipped back into obscurity, slightly more damaged and slightly more famous.

The man who finally brought it back was Fred DeMandel, a Central City native who remembered seeing the submarine as a child. Memory is a tricky thing, especially when it competes with local myth, but DeMandel was persistent. In January 1944, he led the search party that located the wreck by chopping holes in the ice and peering down with a glass bottomed bucket, a method as old fashioned as it sounds. Sheriff Oscar Williams joined the effort, lending official weight to what might otherwise have been dismissed as another tall tale .

When the Nautilus came up, the town treated it like a holiday. Schools closed. Businesses shut their doors. People stood on the ice and watched history be dragged back into the light, mud and all. Inside the hull were the same ballast rocks that had doomed the experiment in 1898, mute witnesses to a miscalculation that had waited nearly half a century to be confirmed. The newspaper accounts noted that no propulsion gear was found, and one official speculated that whatever engine had existed had rusted loose and fallen out through the rotting hull . It was an explanation that satisfied no one completely, which is usually a sign that it is close enough to the truth.

Today, the Rocky Mountain submarine sits in the Gilpin History Museum, surrounded by those original ballast stones. It never traveled a single yard under its own power. It did not change naval warfare or alter the course of history. And yet it matters. It matters because it captures a particular American impulse, the belief that geography is a challenge rather than a limit, and that ingenuity can make even the most unlikely ideas briefly plausible. It also matters because it reminds us that failure is often more interesting than success, and certainly more human.

Owens was not a fraud or a fool. He was an engineer shaped by his time, responding to a world suddenly obsessed with undersea power and secret weapons. He worked with the materials and knowledge he had, in a place that rewarded practical skill and tolerated eccentric ambition. The Nautilus failed because it was unbalanced, unfinished, and perhaps over imagined. It also failed because building a submarine in the Rockies was always going to be an uphill battle, in every sense of the word.

There is a temptation to turn this story into a neat moral lesson about hubris or innovation or the dangers of dreaming too big. It resists that treatment. What remains instead is texture. Cold air on a frozen lake. The scrape of a hull emerging from mud. A band playing a patriotic tune that had no business being there but fit perfectly anyway. History is full of grand successes and catastrophic failures, but it is also full of these odd, stubborn artifacts that refuse to mean just one thing. The Rocky Mountain submarine sits quietly now, no longer sinking or rising, content to be exactly what it is, a reminder that the past is stranger, and often more interesting, than we give it credit.

Further Reading:

Leave a comment