When most people think of the Declaration of Independence, they think of lofty ideals. Life, liberty, the pursuit of happiness. Enlightenment philosophy. Natural rights. All of that is there. But the Declaration is also something else. It is a legal brief. An indictment. A bill of particulars laid before what Jefferson called a candid world.

And among those charges, one stands out for its sheer fury.

It is usually listed as the twenty seventh grievance, and it reads like it was written with a clenched jaw:

“He is at this time transporting large Armies of foreign Mercenaries to compleat the works of death, desolation and tyranny, already begun with circumstances of Cruelty & perfidy scarcely paralleled in the most barbarous ages, and totally unworthy the Head of a civilized nation.”

That is not the voice of reconciliation.

That is not the language of reform.

That is the sound of a door slamming shut.

This grievance matters because it tells us something crucial about when, and why, independence became inevitable.

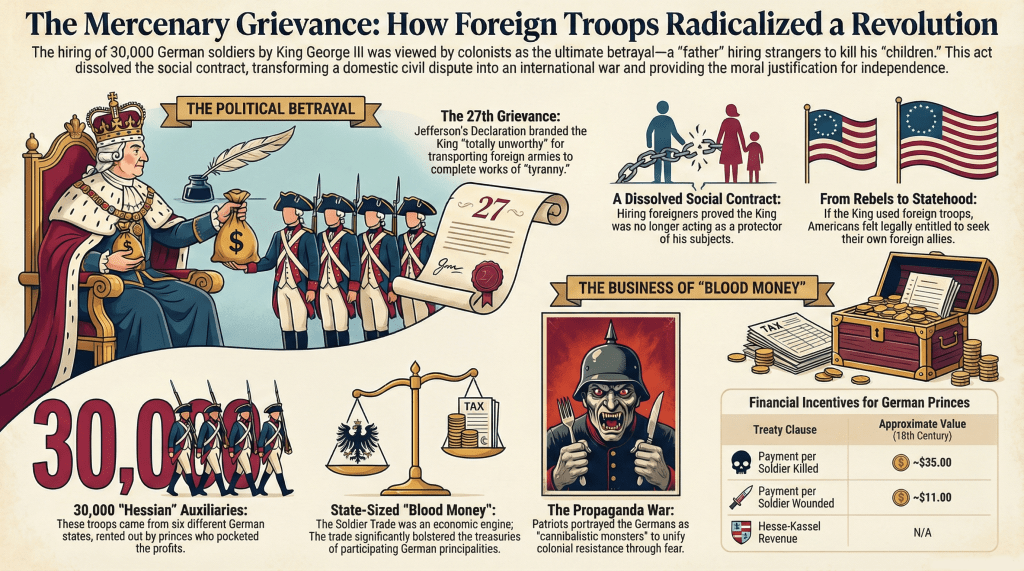

By the time those words were approved in July of 1776, the argument was no longer about taxes or representation or Parliamentary overreach. This was something far older and far more dangerous. It was about the collapse of the social contract itself.

Now, to understand just how serious this accusation was, we have to look at how it was written.

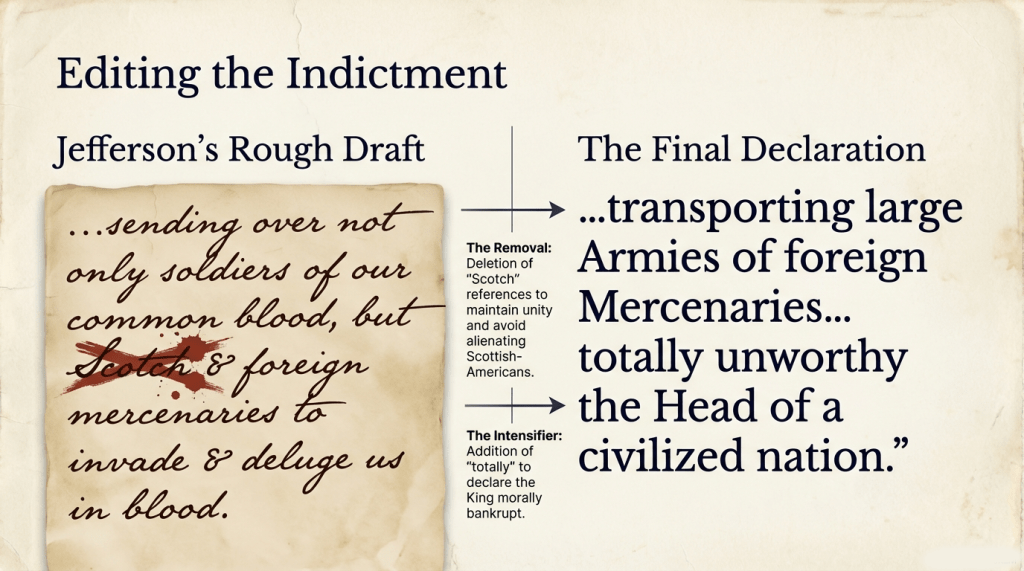

The Declaration did not fall from the sky. It was drafted by a committee of five. Thomas Jefferson, John Adams, Benjamin Franklin, Roger Sherman, and Robert Livingston. Jefferson did the first pass, working quickly and angrily, and his original rough draft was even harsher than what we ended up with.

In that draft, Jefferson accused the King of unleashing “Scotch and foreign mercenaries” to invade the colonies and, in his words, to deluge them in blood.

Congress removed the reference to the Scotch. Not because they suddenly felt charitable toward the Crown, but because politics is the art of knowing who is listening. There were too many Scottish Americans in the colonies, and Congress did not want to alienate people who were already fighting and dying for the Patriot cause.

But here is the key point. While Congress softened other passages in Jefferson’s draft, they did the opposite here.

They made this grievance stronger.

They added the phrase “scarcely paralleled in the most barbarous ages.”

They inserted the word “totally” before “unworthy the Head of a civilized nation.”

That word totally matters.

This was not a casual insult. This was a moral verdict. Congress was not saying that George the Third had made a mistake. They were saying he had disqualified himself.

By eighteenth century standards, this was an extraordinary claim.

Kings were not just political leaders. They were bound by obligation. The Enlightenment social contract, drawing on thinkers like Locke, held that a ruler existed to protect his people. Even a bad king was still presumed to be the father of his subjects.

But when a king hired foreigners to kill his own people, that presumption collapsed.

That is the legal distinction this grievance makes, and it is why it carried so much weight.

Up to this point, the Crown had insisted that the conflict in America was a domestic disturbance. A rebellion. A law enforcement problem. Something to be policed.

But by importing foreign troops, George the Third transformed the nature of the war.

He was no longer acting like a sovereign disciplining wayward subjects. He was acting like a conqueror waging war against a foreign people.

And that mattered.

Because in eighteenth century political theory, a war of conquest dissolved allegiance.

If the King was treating the colonies as an enemy nation, then the colonies were free to act like one.

That is why this grievance is often described by historians as the clinching argument for independence. It provided the moral and legal justification that earlier complaints lacked.

Taxes could be debated. Trade regulations could be reformed. Even bloodshed, tragic as it was, could be framed as an excess of enforcement.

But foreign mercenaries changed the story.

It told the colonists that the King no longer saw them as his people.

And once that realization set in, there was no path back.

What makes this grievance even more striking is how deliberately it avoids legal technicalities. This is not a complaint about statutes or procedures. It is an accusation about character.

The Declaration does not say this action was illegal.

It says it was barbaric.

It says it was cruel.

It says it was perfidious.

And finally, it says it was totally unworthy of a civilized ruler.

Those words were chosen carefully.

Civilization mattered deeply to the eighteenth century mind. To be civilized was to be restrained, lawful, ordered. To hire foreign troops to suppress your own people was something associated with despots and tyrants, not constitutional monarchs.

In other words, Congress was stripping George the Third of his moral standing.

They were telling the world that whatever claims he might make to legitimacy had been forfeited.

And that message was not just for Americans.

It was for Europe.

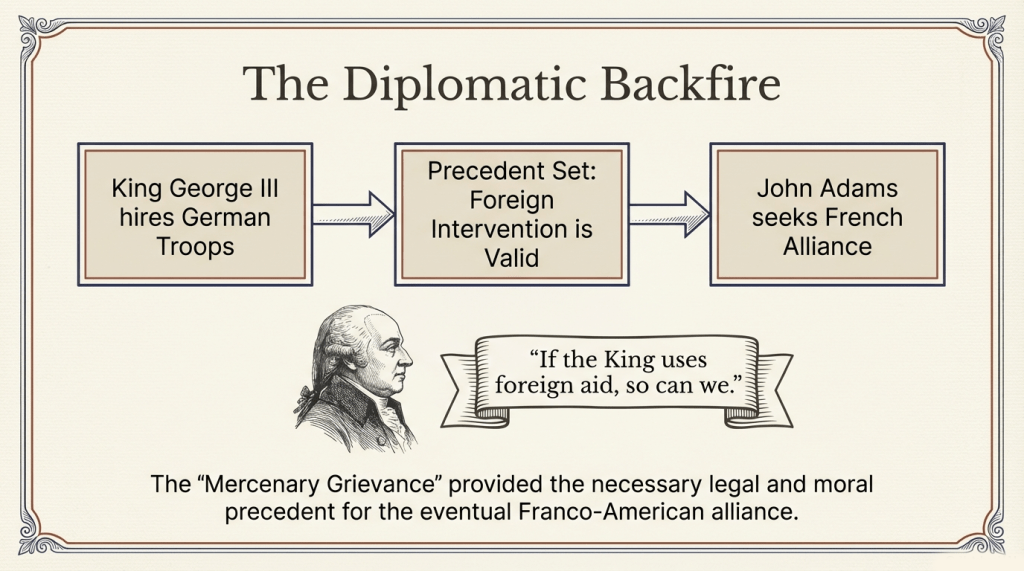

Men like John Adams understood this immediately. If the King had hired foreign troops, then the colonies were justified in seeking foreign allies of their own. The grievance did not just justify independence. It opened the door to diplomacy.

France could now be approached not as a meddler in a British civil dispute, but as an ally in a war between nations.

That argument rested heavily on this charge.

And it is worth pausing here to recognize just how final this moment was.

The Declaration is sometimes remembered as optimistic and hopeful. But this passage is neither. It is grim. It is cold. It is unsentimental.

It is the language of people who have concluded that reconciliation is no longer possible.

Once you accuse a king of unleashing barbarism and tyranny through foreign arms, you are not asking him to reconsider. You are announcing that his authority has ended.

That is why this grievance sits where it does in the document. Late. After patience has been exhausted. After warnings have been ignored. After appeals to shared history have failed.

This is the point where the colonies stop arguing and start judging.

And that judgment is severe.

George the Third is not merely wrong.

He is not merely unjust.

He is totally unworthy.

Those are not the words of subjects.

Those are the words of a people who already see themselves as something else.

By the time Congress approved this language, the break had already happened in the hearts of the colonists. The arrival of foreign troops did not create that rupture, but it made it undeniable.

And in the next segment, we are going to look at how that decision was made, how the soldier trade worked, and why thousands of German troops were suddenly crossing the Atlantic to fight a war they barely understood.

But here, at the start, this is the core truth.

Independence was not declared because Americans wanted to be free in the abstract.

It was declared because the King chose to make war on them as if they were already foreign.

And once he did that, the old world ended.

Once you accuse a king of transporting foreign mercenaries, the next question is obvious. Where did they come from, and why were they available for hire in the first place?

The short answer is not ideology.

It is not loyalty.

It is not even really war.

It is business.

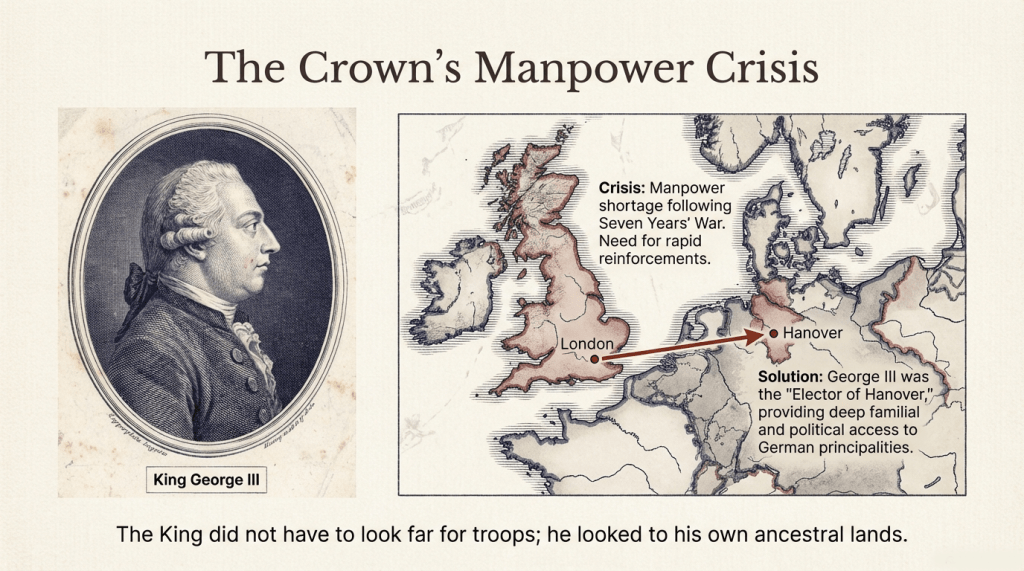

By the early 1770s, Britain had a manpower problem. The Seven Years War had been long, brutal, and expensive. The British Army was stretched thin policing a global empire. Ireland needed troops. The Caribbean needed troops. India needed troops. And now, suddenly, North America was in open rebellion.

Raising tens of thousands of new British soldiers would take time, money, and political capital that Parliament did not have. Impressment was unpopular. Recruitment was slow. Casualties were high.

So Britain did what European powers had been doing for generations.

It went shopping.

Germany at this time was not Germany as we think of it today. It was a patchwork of small principalities, duchies, and electorates, many of them poor, militarized, and ruled by princes who treated their armies as revenue generating assets.

And George the Third had a particular advantage here.

He was not just King of Great Britain. He was also Elector of Hanover. That meant he was deeply embedded in the web of German dynastic politics. He had cousins, in laws, and long standing relationships across the German states.

When Britain needed soldiers, Germany was where it looked.

Americans, then and now, lumped all of these troops together under one name. Hessians.

But that label hides more than it reveals.

Roughly thirty thousand German troops served in North America during the Revolutionary War, but they came from at least six different states. Hesse Kassel supplied the majority, but others came from Hesse Hanau, Brunswick, Anspach Bayreuth, Waldeck, and Anhalt Zerbst.

These men spoke different dialects, wore different uniforms, and served under different officers. The only thing they had in common was that their princes had signed contracts with the British Crown.

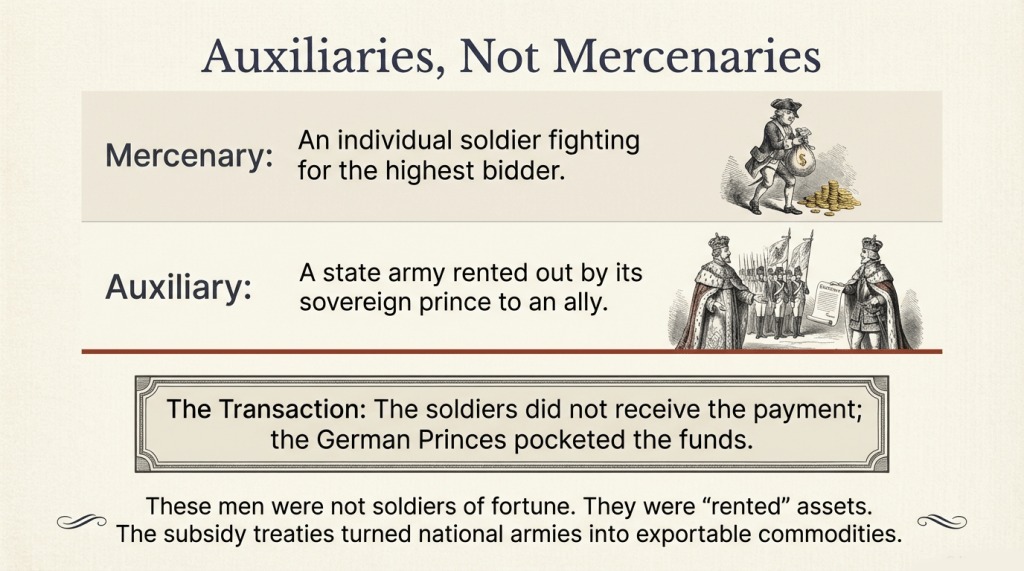

And here is where a critical distinction matters.

These soldiers were not mercenaries in the modern sense. They were not individuals selling their services for personal profit.

They were auxiliaries.

That is the historical term, and it matters because it reveals where the money went.

The British government did not pay the soldiers. It paid their rulers.

The agreements were called subsidy treaties. Under these treaties, Britain paid a flat rate for each soldier supplied, covered their transport and equipment, and paid additional fees for casualties.

In effect, Britain was leasing entire armies.

For some German states, this was not a side hustle. It was the economy.

In Hesse Kassel, renting out the army generated revenue equivalent to more than a decade of tax receipts. The money funded palaces, court expenses, and domestic projects. The state became wealthy by exporting its sons.

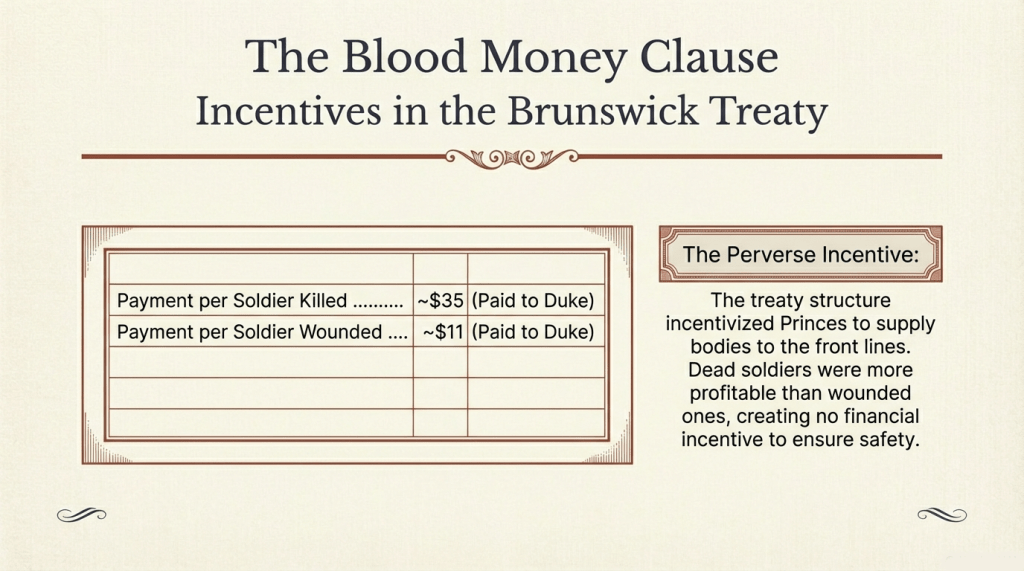

And the most chilling part of these treaties was what Americans quickly labeled blood money.

In the agreement with the Duke of Brunswick, Britain agreed to pay roughly thirty five dollars for every soldier killed and about eleven dollars for every man wounded.

Let that sink in.

Dead soldiers were profitable.

Wounded soldiers were less so.

This clause horrified Americans, and rightly so. It appeared to place a price tag on human life. Worse, it created an incentive structure where princes benefited financially from the deaths of their own men.

Whether that incentive actually influenced battlefield behavior is debated, but the perception alone was damning.

From the American point of view, this was not just war. It was commodified violence.

It confirmed everything the Declaration claimed.

Foreign troops were not being sent to restore order or enforce law. They were being deployed because someone had signed a contract and someone else was getting rich.

And this helps explain why the grievance language is so savage.

The Declaration does not accuse the King of poor strategy. It accuses him of cruelty and perfidy.

Perfidy means betrayal.

The betrayal here is layered.

The King betrayed his subjects by hiring foreigners to kill them.

The German princes betrayed their own people by selling them.

And the entire system reduced human beings to line items in a ledger.

It is worth noting something else that often gets lost.

Most of these German soldiers did not volunteer.

Military service in many of these states was compulsory. Young men were conscripted, trained, and shipped overseas with little say in the matter. Desertion was punished harshly. Families were left behind.

In other words, the men Americans feared were often victims of the same system that employed them.

But that nuance was irrelevant in 1776.

What mattered was what their presence symbolized.

To the American imagination, these troops represented everything that was alien, unaccountable, and dangerous about imperial power. They were not neighbors. They were not fellow Englishmen. They were not bound by shared customs or restraint.

They were outsiders, hired to do a job.

And that job was suppression.

From the British perspective, this all made cold sense. The soldier trade was legal, established, and efficient. European powers had used auxiliaries for centuries. Nothing about it violated the norms of eighteenth century warfare.

But revolutions are not judged by norms alone.

They are judged by how people feel when norms collide with lived experience.

And for Americans already wary of standing armies, already suspicious of distant authority, already bleeding from Lexington, Concord, and Bunker Hill, the arrival of thousands of foreign troops felt like confirmation that the Crown no longer cared how this war ended, only that it ended in submission.

That perception mattered more than legal definitions.

Because once a people believes that its ruler has turned war into a transaction, trust does not survive.

And that is the pivot point of this segment.

The soldier trade explains how Britain fought the war.

But it also explains why the war radicalized so quickly.

When violence is outsourced, it feels absolute.

When killing is subcontracted, it feels final.

And sometimes the people hired to destroy a nation end up becoming part of it.

If the mercenary grievance explained why independence could be justified, this is the part that explains why it became inevitable.

Because politics may begin in arguments, but revolutions are carried forward by emotion. And nothing stirred colonial emotion quite like the arrival of foreign troops.

For many Americans, this decision landed not as strategy, but as betrayal.

For more than a decade, colonists had told themselves a comforting story. Parliament was the villain. Corrupt ministers. Bad laws. Misguided policies. The King, they insisted, was distant but ultimately benevolent. A father misled by bad advisors.

The arrival of German troops shattered that illusion.

This was no longer a family quarrel. This was not discipline. This was outsourcing violence.

In sermons, newspapers, taverns, and private letters, the language turns personal. The King is no longer misguided. He is treacherous. A father who has hired strangers to kill his children.

That sense of betrayal matters because it refocused American anger.

Until this point, much of the colonial rage had been aimed sideways. At Parliament. At customs officials. At bureaucrats enforcing unpopular laws. The German troops changed the target.

Now the finger pointed directly at George the Third.

And once that happened, reconciliation was not just unlikely. It became unthinkable.

Fear filled the gap where loyalty had once lived.

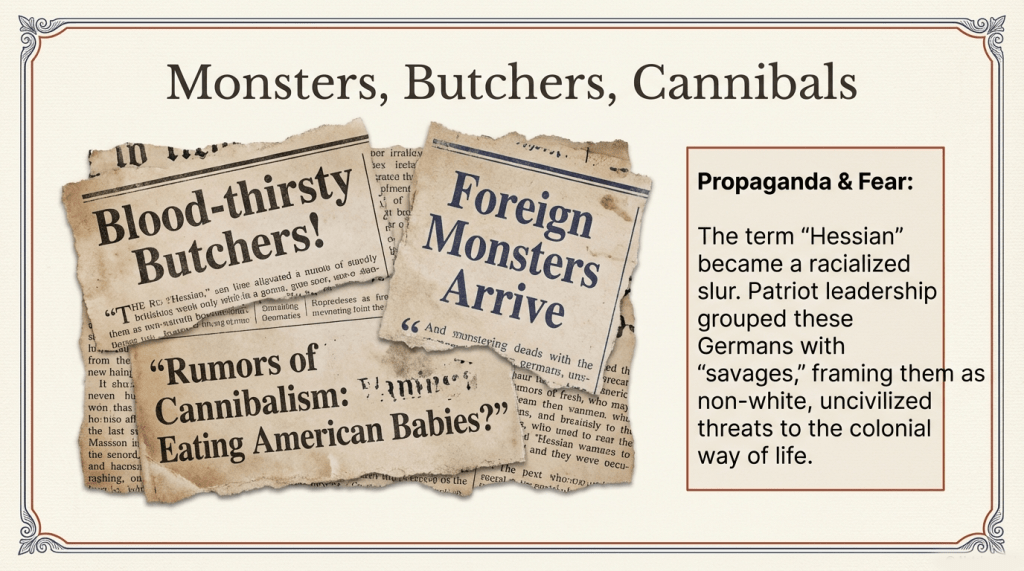

Patriot leaders understood this instinctively and they leaned into it. Hard.

The German troops were not presented as disciplined professionals. They were portrayed as monsters. Blood thirsty butchers. Hired killers with no conscience. Newspapers described them in lurid detail, often inventing atrocities before a single one had occurred.

Rumors spread that they were cannibals. That they would eat American children. That they were barely human.

This was propaganda in its rawest form, and it worked.

The word Hessian itself became a slur. It was racialized, lumping Germans together with Native Americans and enslaved Africans as uncivilized threats unleashed by a tyrannical king.

This is uncomfortable history, but it is honest history.

Fear is a powerful unifier. By portraying the Germans as an existential menace, Patriot leaders created a common cause among colonies that otherwise had little in common. New England farmers, Virginia planters, and Pennsylvania merchants could all agree on one thing.

These people do not belong here.

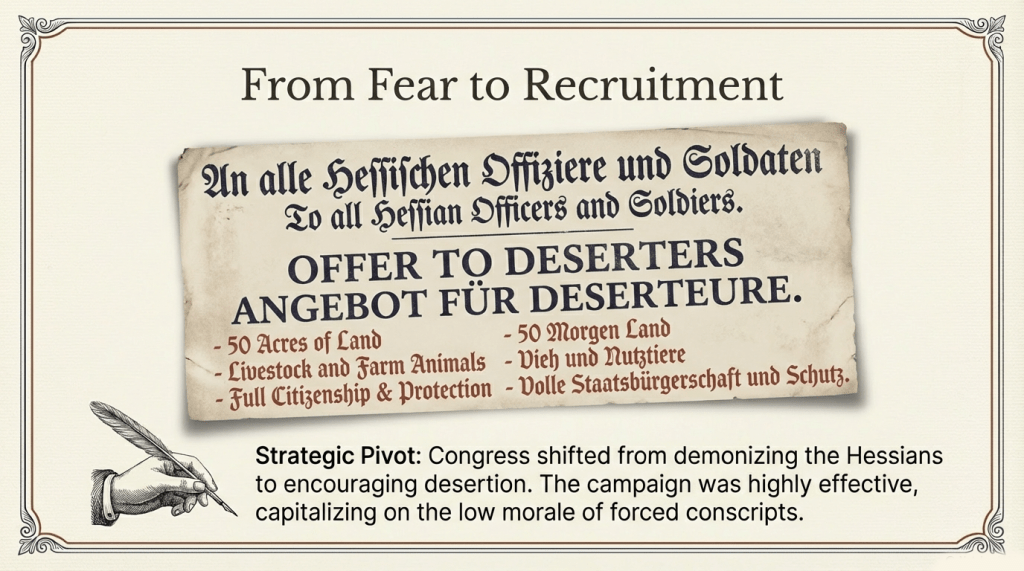

What makes this campaign especially striking is how quickly it flipped.

At first, the goal was terror. To rally resistance. To harden resolve.

But reality has a way of intruding.

When American forces actually encountered German troops, especially after battles like Trenton, a different picture emerged. Prisoners were not monsters. They were tired, cold, confused men who often had no idea why they were fighting in America at all.

Many had been conscripted. Many were deeply religious Lutherans who found themselves fighting people who read the same Bible. Many simply wanted to go home.

Congress noticed.

And quietly, without fanfare, American policy shifted.

Instead of demonization, the new tactic was seduction.

The Continental Congress began offering incentives to German soldiers who deserted. Fifty acres of land for enlisted men. Livestock. Tools. Protection of religious freedom. Citizenship.

In other words, everything the Declaration accused the King of denying.

This was not just kindness. It was strategy.

American leaders realized that the fastest way to neutralize these troops was not to kill them, but to absorb them. To turn hired soldiers into settlers. To convert fear into population.

And it worked.

Thousands deserted. Some slipped away quietly. Others surrendered and never went back. Between five and six thousand German soldiers remained in America after the war, forming the backbone of German American communities that still exist today.

Here is the irony that history delights in.

A grievance meant to condemn tyranny became an immigration story.

The same men described as barbarous mercenaries in 1776 were, within a generation, farmers, craftsmen, and citizens of the republic they had been hired to destroy.

But the diplomatic consequences of the mercenary grievance may have mattered even more.

John Adams understood this better than anyone.

If the King could hire foreign troops, then the colonies could seek foreign allies. That was the logic. And it was persuasive.

France had been cautious. Supporting a rebellion against Britain was risky. It could be seen as interference in a domestic dispute. But once Britain treated the colonies as a foreign enemy by importing German troops, that objection vanished.

The war was no longer internal.

It was international.

And that opened the door to French arms, French money, French ships, and eventually French soldiers.

In a very real sense, the mercenary grievance helped make Yorktown possible.

This is the backfire that seals the story.

By attempting to crush the rebellion with foreign troops, George the Third legitimized the rebellion’s appeal to foreign powers. By treating the colonies as an enemy nation, he helped turn them into one.

And the emotional damage was irreversible.

Even had Britain won militarily, the relationship was broken beyond repair. Trust does not survive when a ruler turns his subjects into a market.

That is why the Declaration lingers on this grievance. Why it uses language so severe that it feels almost excessive.

Because this was the moment when Americans stopped seeing themselves as Englishmen with complaints and started seeing themselves as a people apart.

Not because they wanted novelty.

But because the old relationship had become morally impossible.

The mercenary grievance did not just justify independence.

It made coexistence morally incoherent.

And that is the final lesson of this episode.

Revolutions do not begin when people want something new. They begin when the old order becomes unbearable.

When authority feels alien.

When power feels transactional.

When loyalty feels foolish.

George the Third may have believed he was solving a manpower problem.

What he actually did was convince a continent that he was no longer worthy of their allegiance.

And once that belief took hold, the outcome was only a matter of time.

Leave a comment