There are some images that history hands us fully formed, without apology or explanation. The shark teeth painted on the nose of a Curtiss P 40 Warhawk is one of them. It does not ask permission. It does not wait for context. It simply grins, a flash of white menace against olive drab, and dares the viewer to mistake it for decoration. Over the years it has been reproduced endlessly, on jackets, posters, coffee mugs, and model boxes, often divorced from the circumstances that gave it meaning. The danger in that kind of fame is that it can flatten a story that was never simple. The American Volunteer Group, remembered as the Flying Tigers, has suffered that fate more than most. They are remembered as mercenaries, heroes, cowboys of the sky, or symbols of American defiance before Pearl Harbor. They were, in truth, something far stranger and more revealing. They were a workaround, a gamble, and a human experiment conducted under the pressure of a world already breaking apart.

What The Frock – The Musical

The war in China did not begin in 1941, and it did not begin neatly. By the time American volunteers ever laid eyes on a P 40 in Southeast Asia, China had been fighting for years. Japanese forces had invaded Manchuria in 1931 and expanded steadily southward, testing the limits of international outrage and finding very few. By 1937, the conflict had widened into full scale war. Chinese cities burned. Refugees fled inland. The Chinese Air Force, brave and painfully outmatched, flew whatever aircraft could be purchased or donated. American, Soviet, Italian, German, and British designs all appeared briefly in Chinese markings, usually before being destroyed. Pilots arrived from abroad with good intentions and uneven preparation. They faced a Japanese air arm that was disciplined, aggressive, and modern, backed by industrial strength and doctrinal clarity.

In this environment, air combat was not romantic. It was a slaughter. Chinese pilots flew outdated machines against faster, better coordinated opponents. Losses mounted. Morale suffered. The sky became a place of inevitability rather than opportunity. It was into this situation that Claire Lee Chennault arrived, carrying a lifetime of grudges, convictions, and notebooks full of observations that Washington had never wanted to hear.

Chennault had been an officer in the U.S. Army Air Corps and a relentless critic of prevailing air power theory. While others championed high altitude strategic bombing as the decisive future of war, Chennault argued that fighters mattered, that air superiority could not be assumed, and that bombers were not invulnerable. He made these arguments loudly and repeatedly. He paid for it with stalled promotions, strained relationships, and ultimately forced retirement on medical grounds. When he arrived in China in 1937 as an adviser to Chiang Kai shek, he was a man who felt discarded by his own institution. China gave him something the United States no longer would. It gave him relevance.

Chennault watched Japanese pilots carefully. He studied their formations, their attack patterns, their habits. He noted their strengths and their weaknesses. He also observed the fatal errors Chinese pilots made, not from cowardice, but from training that did not match reality. He concluded that dogfighting doctrine taught in American and European schools would get pilots killed in Asia. Japanese fighters were lighter, more maneuverable, and better suited to turning engagements. Trying to outturn them was suicide. Speed, altitude, and discipline were the only counters.

At the same time, political maneuvering was underway thousands of miles away. The Roosevelt administration understood that China was a strategic dam holding back Japanese expansion. If China collapsed, Japanese forces could redeploy southward and westward with even greater force. Yet the United States was still officially neutral, constrained by the Neutrality Acts and a public deeply wary of another foreign war. The solution that emerged was neither honest nor entirely dishonest. It lived in the gray space where governments often operate when events outpace law.

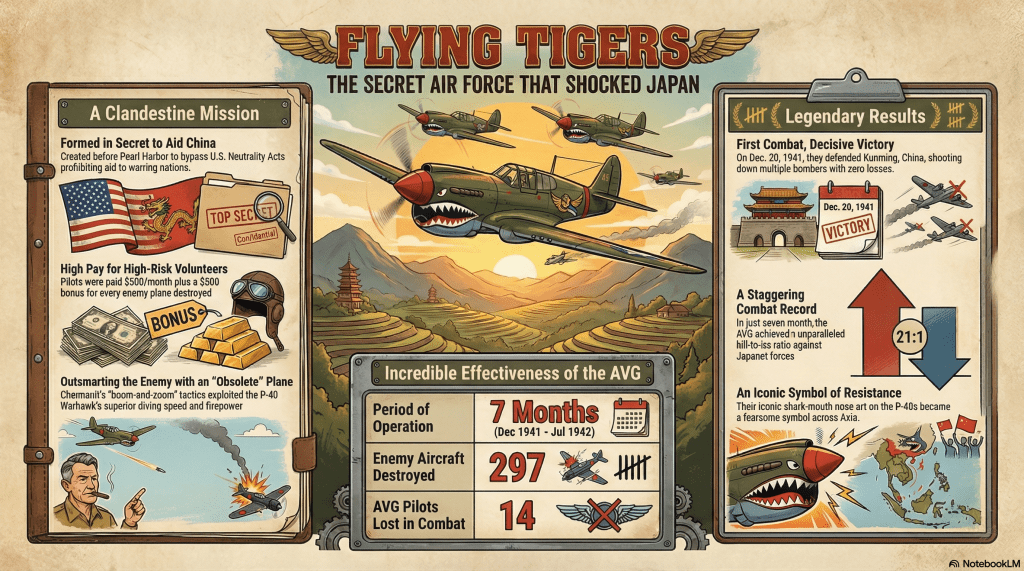

In April 1941, Roosevelt quietly authorized a plan that allowed American military pilots to resign their commissions and accept civilian contracts with a private company, the Central Aircraft Manufacturing Company. CAMCO would employ them to fly and maintain aircraft for China. On paper, they were civilians. In reality, they were an extension of American policy carried out without uniforms. One hundred Curtiss P 40 fighters, originally intended for Britain, were diverted. Money flowed through intermediaries. Diplomatic language remained careful. Everyone involved understood the fiction. Everyone pretended it mattered.

Recruitment focused on experienced pilots from the Army, Navy, and Marine Corps. They were offered salaries far above military pay, often around seven hundred fifty dollars a month, with bonuses for confirmed aerial victories. For young men accustomed to modest officer wages, it was a powerful lure. Some joined out of idealism. Some wanted adventure. Some wanted money. Most wanted to fly and fight on their own terms. They signed contracts, turned in commissions, and boarded ships headed for an unfamiliar war.

Training began in Burma and China in the summer and fall of 1941. Chennault ran what pilots jokingly called the kindergarten. It was not gentle. He demanded that they unlearn habits drilled into them for years. He banned turning fights. He emphasized discipline over individual flair. He taught what he called defensive pursuit, attacking from altitude, diving with speed, firing in a single pass, and disengaging immediately. Survival mattered more than glory. Pilots who could not accept that did not last.

The aircraft they flew, the Curtiss P 40, was neither miracle nor failure. It was rugged, heavily built, with armor plating and self sealing fuel tanks that could absorb punishment. It could dive fast and hold together. It could not climb quickly. It could not turn tightly. Against Japanese Army fighters like the Ki 27 and Ki 43, it was at a disadvantage if mishandled. Against physics, it was honest. Used correctly, it gave pilots a chance.

Equally important was what never flew at all. Chennault constructed a massive ground observer network stretching across China and Burma. Villagers, soldiers, and civilians watched the skies with binoculars and telephones, reporting aircraft movements in real time. Information flowed to operations centers, giving pilots warning and altitude. It was crude, human, and remarkably effective. It turned minutes into lives.

The shark mouth appeared almost casually. Some pilots had seen similar designs on British aircraft. Others remembered photographs of German planes. Charlie Bond and Erik Shilling adapted the idea to the P 40’s blunt nose. It looked right, predatory and faintly mocking. The nickname Flying Tigers emerged through American support groups and was solidified by a Walt Disney designed insignia. None of this mattered on December 20, 1941, when Japanese bombers approached Kunming.

That first combat came twelve days after Pearl Harbor. The Japanese did not know the American Volunteer Group was operational. The warning network worked. Pilots scrambled and gained altitude. Diving attacks shattered the bomber formation. Bombs were jettisoned early. Several aircraft were destroyed. One American pilot ran out of fuel and crash landed, alive but stranded. Kunming was spared. For the Chinese population, it was electrifying. For the Allies, it was the first confirmed air victory in the Pacific after Pearl Harbor. The psychological value was enormous.

The war did not pause. The AVG split its forces. Two squadrons remained in China to defend Kunming and supply routes. The third, the Hell’s Angels, deployed to Rangoon to defend the Burma Road, the fragile lifeline feeding China from the outside world. There the air war intensified. Japanese bombers came in waves. RAF Brewster Buffalos joined the defense, flown by pilots whose courage exceeded their aircraft’s capabilities.

On December 23 and again on Christmas Day 1941, Rangoon was attacked heavily. Allied fighters claimed dozens of enemy aircraft. Losses were real and mounting. Pilots flew multiple sorties a day. Maintenance crews worked miracles with limited parts. Fatigue became constant. The Japanese adapted, pressing harder. A tragic friendly fire incident in February 1942 underscored the chaos of coalition warfare under pressure.

As Japanese ground forces advanced, Rangoon became untenable. By March 1942, the city fell. The AVG retreated northward, relocating repeatedly as the front collapsed. Aircraft wore out. Pilots were lost to combat, accidents, and exhaustion. The Burma Road was cut, replaced by the hazardous airlift over the Himalayas known simply as the Hump. Yet even as their situation deteriorated, the AVG continued to strike back.

In March 1942, they launched a daring low level raid against Japanese airfields at Chiang Mai in Thailand. Surprise was essential. Pilots flew long distances over hostile territory. Charlie Bond led strafing runs against parked aircraft. Others attacked fuel and infrastructure. One pilot, William McGarry, bailed out after engine trouble and was captured, later rescued through a web of resistance that included the OSS and Thai allies. Jack Newkirk, known as Scarsdale Jack, was killed during a strafing run, his aircraft continuing briefly before crashing. The raid destroyed aircraft and disrupted Japanese operations. It also highlighted the cost. The AVG could hit hard, but it could not do so without bleeding.

In May 1942, Japanese forces threatened to cross the Salween River Gorge, a natural gateway into China. Chennault’s pilots, now flying P 40s equipped with bomb racks, attacked relentlessly. Tex Hill led missions that bombed and strafed advancing columns, collapsing bridges and choking roads with wreckage. The Japanese advance stalled. China held. It was not a grand strategic victory, but it mattered in the only way war ever truly measures success. The enemy did not get through.

By the summer of 1942, the fiction sustaining the AVG had outlived its usefulness. The United States was fully at war. The American Volunteer Group was politically awkward and administratively inconvenient. Friction grew between Chennault and senior Army leadership, particularly General Joseph Stilwell, whose views on air power and China diverged sharply. Colonel Clayton Bissell handled the transition poorly, threatening volunteers with the draft if they did not accept induction. Trust collapsed.

On July 4, 1942, the American Volunteer Group was officially disbanded. The 23rd Fighter Group of the U.S. Army Air Forces replaced it. Only a small number of pilots and ground crew accepted induction. Most returned home or later rejoined their original services on their own terms. Tex Hill stayed briefly to ensure continuity, then moved on. Chennault remained, eventually commanding the Fourteenth Air Force and continuing the air war over China.

In seven months of combat, the AVG claimed nearly three hundred enemy aircraft destroyed, with remarkably low combat losses by comparison. Exact numbers vary by source and always will. What does not vary is their impact. At a moment when Allied news was relentlessly bleak, the Flying Tigers offered proof that the enemy could be fought and beaten. They protected China when it mattered. They bought time.

Recognition came late. In 1991, surviving members were retroactively recognized as U.S. veterans and awarded the Presidential Unit Citation. Museums and memorials followed, in China and in the United States. The shark teeth became immortal.

What remains beneath the legend is a story about improvisation, restraint, and survival. The Flying Tigers were not saints. They were not simple heroes. They were professionals operating in a gray zone created by political necessity. They adapted or died. In a century crowded with noise and easy narratives, that reality deserves to be remembered without polish.

Leave a comment