There are winters when history stands very still, almost as if the world is bracing for something it already knows it cannot avoid. The winter of 1860 felt like that. One can imagine the heavy December air in Washington settling over the capital like a thick blanket that even the most stubborn stove fires could not quite chase away. The legislators walked through the corridors with forced conversations and polite nods, but there was a hollow ring to every greeting. The nation had reached a point where its disagreements were no longer political quarrels but questions about the very structure of its future. Abraham Lincoln had been elected with a firm pledge that slavery would not expand into the territories. To the Deep South, this was something far beyond a routine policy dispute. It sounded like a warning bell. It sounded like a door closing. It sounded, to many, like the first quiet toll of a funeral.

What The Frock – The Musical

South Carolina prepared to leave the Union almost immediately. The other Deep South states watched closely, as though they were guests in a room where one person had stood up to make a dramatic exit. Everyone waited to see who would follow. Senators slipped away from Washington to attend secession conventions. Others lingered with embarrassed glances at their colleagues across the aisle. The sense of paralysis in the capital grew by the day. The newspapers called it a crisis, but there was something more elemental at stake, something deeper than politics. Nations sometimes discover that their disagreements have grown larger than the tools they once used to manage them. That realization was just beginning to dawn.

Into this charged atmosphere walked Senator John J. Crittenden of Kentucky. He was respected. He was seasoned. He had the slightly weary look of a man who had spent a lifetime sealing cracks in the political plaster, only to discover that new fissures had appeared behind him. He had served in almost every role a government could offer. He had lived through the Missouri debates of 1820. He had watched Henry Clay, the great pacificator, turn political bitterness into workable compromise. Crittenden carried that older tradition with him like a set of well worn tools passed down from one craftsman to the next. He believed in those tools. He believed that compromise was not weakness but a mark of mature statesmanship. He believed that the Union could still be saved if only the right words were spoken in the right order.

He could not have known that the country he was trying to save had already moved past the era in which those tools could work. Traditions age. Ideas stiffen. Sometimes a nation outgrows a method without realizing it. Crittenden represented the last of the old guard, the final echo of an age that believed any crisis could be contained inside the walls of the Capitol with patience and negotiation. That belief was noble. It was comforting. It was also a decade too old for the world that existed in December 1860. Still, Crittenden rose on the Senate floor on December eighteenth and presented his grand solution. He offered not a small patch nor a temporary repair. He offered a final settlement.

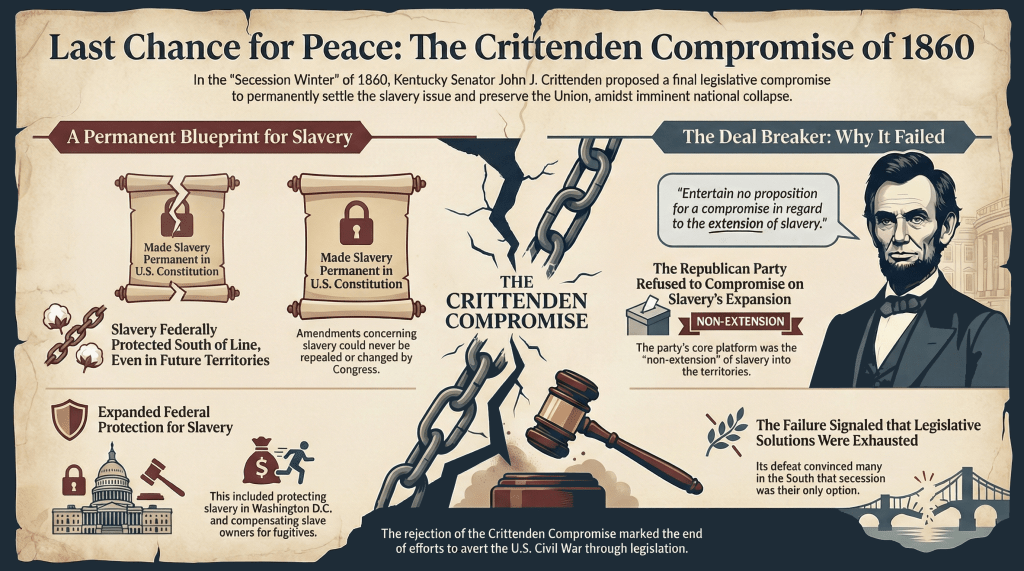

The Crittenden Compromise was sweeping. It was built with the scale of a man who truly wanted to avert war. It contained six constitutional amendments and four congressional resolutions. Every component was meant to create permanence. Every clause signaled a desire to put the sectional conflict to rest once and for all. It was, in many ways, an attempt to repeat the great moments of legislative pacification that Clay and Webster had achieved. Crittenden believed that if the country could be brought to a unanimous agreement on a constitutional structure, then the fires of secession might cool. The problem was that the tools that had succeeded before were now aimed at a country that no longer recognized its reflection.

To understand why, one must look backward. The Missouri Compromise of 1820 had placed a line across the continent. North of the line, slavery was banned. South of it, slavery was permitted. The arrangement was not elegant, but it calmed tempers. Thirty years later the Compromise of 1850 arrived with an even more delicate exchange: California entered as a free state, while the Fugitive Slave Act was strengthened. One concession balanced the other. Both sides grumbled, yet both sides sighed with relief. For a time, these balancing acts preserved the fragile equilibrium.

Then came the Kansas Nebraska Act. It opened the territories to popular sovereignty and effectively wiped away the Missouri line. What followed was not calm debate but violence. Kansas became a battlefield where partisans fought to determine the fate of slavery with rifles rather than ballots. The Supreme Court then delivered the Dred Scott decision. It declared that African Americans were not citizens and that Congress could not prevent slavery in the territories. The decision was meant to clarify. Instead, it poured oil upon dry leaves.

The nation did not merely quarrel. It rearranged itself politically. The Republican Party rose rapidly on the principle that slavery must not expand. This was more than a policy. It became a point of identity. The South saw it as a threat to its social structure. The Republicans saw it as a moral necessity. In a world where the political center had been shaken to pieces, the old calculus of compromise began to wobble.

President James Buchanan responded with remarkable hesitation. He believed secession was illegal. He also believed the federal government had no constitutional authority to bring a state back by force. In essence, he told the country that the house was on fire, but the constitutionally appropriate water hose could not be located. This combination of paralysis and principle deepened the crisis. Into this vacuum stepped Crittenden with his compromise, a plan that he hoped would build a bridge across a canyon that was widening by the hour.

His proposal aimed to restore the old formula. It reinstated the Missouri Compromise line of 36 degrees 30 minutes and extended it to the Pacific Ocean. The brilliance or the folly of the plan, depending on one’s view, lay in a few deceptively simple words: territories now held or hereafter acquired. Those words carried a heavy freight. They opened the possibility that future acquisitions, perhaps from Mexico, perhaps from Cuba, perhaps from Central America, might become slaveholding regions. This concept was central to Southern dreams of expansion. It was also central to Northern fears of a system that sought to spread itself across the hemisphere.

North of the line slavery would be prohibited. South of the line slavery would receive federal protection. This was geographic certainty, a return to an older system that many had once considered workable. Yet the implications for the future were enormous. The South could grow politically only through expansion. The Republicans opposed expansion because they believed slavery must be put on the path to eventual extinction. The two visions could not meet in the middle.

Other parts of the compromise dealt with familiar issues. Slavery would be protected in federal enclaves within slave states. Congress would not abolish slavery in the District of Columbia unless the local residents requested it and unless Maryland and Virginia abolished it first. Interstate transport of slaves would be beyond congressional interference. The federal government would even compensate slave owners if a fugitive slave were rescued through violence or persuasion, thereby placing the financial burden upon Northern taxpayers. These measures sought to smooth the friction points that had led to repeated complaints from the South. They also made many Northerners feel as if the compromise asked them to pay for a system they opposed.

The final amendment attempted something extraordinary. It aimed to make these provisions permanent, unchangeable, and beyond amendment. It sought to freeze the constitutional position of slavery forever. This was not a compromise that deferred the problem. This was a compromise that aimed to end the debate permanently by locking the issue behind legal iron.

The four congressional resolutions asked Northern states to repeal their Personal Liberty Laws, which hindered enforcement of the Fugitive Slave Act. They also proposed small adjustments to the act to make it slightly more palatable. These gestures attempted to demonstrate that Crittenden wanted peace, not domination. But the goodwill could not overcome the magnitude of the constitutional changes.

The Senate formed the Committee of Thirteen to examine the compromise. Its membership was a who’s who of the moment. Jefferson Davis, Robert Toombs, William Seward, Stephen Douglas, and others gathered around a table that seemed almost too small for their collective ambition and stubbornness. The committee looked impressive. It was also unworkable. The members arrived with firm instructions from their homes. Southern members insisted that the compromise would mean nothing unless Republicans embraced it. They wanted political cover. They wanted to show the South that the North had agreed to protect slavery by constitutional right. Republicans refused to endorse a plan that contradicted the very reason for their party’s existence.

The vote on December twenty second revealed the truth. The Republicans rejected the plan. Crittenden saw his hope collapse, not because the concept was flawed in principle, but because the country had reached a point where no group could give what the other required. The moment belonged to the calculation of national power, not the gentle art of agreement.

Hovering just beyond the committee room, Abraham Lincoln exerted enormous influence through silence. He avoided public declarations, a tactic he considered wise, but he flooded his allies with stern private messages. He told Lyman Trumbull and Elihu Washburne that no compromise on the expansion of slavery should be entertained. His reasoning was cold and clear. If Republicans abandoned their core promise before even taking office, they would betray their voters. More importantly, they would reward secession through concession. They would signal that disunion was an effective bargaining tactic. Lincoln believed that yielding on expansion would destabilize the Union by encouraging future brinkmanship. He also believed that expansion was not a theoretical matter. There were Southern leaders who dreamed of acquiring Cuba or building a Central American empire. Protecting slavery in future acquisitions would create perpetual conflict.

Yet Lincoln was not entirely rigid. He supported the Corwin Amendment, which promised noninterference with slavery in the states. This revealed a distinction in his thinking, a difference between tolerating slavery where it already existed and endorsing its growth. This distinction mattered to him. It mattered to his supporters. It mattered to the future of the Republican Party.

Outside Congress, the public responded with urgency. Petitions arrived from Northern merchants who feared that war would destroy the economy. Moderates urged adoption of the compromise. They wrote letters filled with worry about jobs, trade, and livelihoods. These were not abstractions. These were the concerns of ordinary people who knew that when a nation tears itself in two, it is always the people who pay the bill.

The Senate considered the compromise again on January sixteenth. It failed once more, but the vote revealed something important. Several Southern senators abstained. Had they voted in favor, the proposal might have stayed alive. Their abstention showed that compromise was no longer their goal. They were preparing to leave the Union and had no desire to rescue it. They no longer sought adjustment. They sought independence. The compromise died not only because Republicans opposed expansion, but because the South no longer believed compromise could protect what they valued most.

As March approached, the Senate tried again and defeated the measure on the second of the month. The last political bandage had fallen away. What remained was the bare wound.

In a final gesture, the Peace Conference of 1861 assembled in Washington. John Tyler, the former president, presided over an assembly of elder statesmen. They crafted proposals, including a version similar to Crittenden’s. Congress ignored them. The nation had moved into a different phase, where polite gatherings of older men no longer commanded the attention they once did.

The Corwin Amendment passed, offering protection to slavery in the states, but it mattered little. It addressed the wrong fear. The South believed it needed expansion to maintain its political parity and social structure. Corwin guaranteed safety only for the present. It offered nothing for the future. It soothed very few.

When the compromise failed, something deeper than legislation died. The old belief that America could fix its problems with words and bargains slipped away. The era of Clay, Webster, and Crittenden faded into memory. The idea that another careful arrangement could preserve national unity crumbled.

Crittenden’s compromise was not rejected because it was poorly crafted. It was rejected because America had outgrown the possibility of such settlements. The North believed that expansion of slavery threatened the nation’s future. The South believed that restriction of slavery threatened its own. These were not positions that could be reconciled through geographic lines or subtle language. They were visions of incompatible futures.

The compromise became a symbol of finality. A sign that the nation had crossed an invisible threshold. A reminder that political systems can reach a point where the tools of the past no longer fit the problems of the present.

When the first cannon fired on Fort Sumter, the country finally understood what Crittenden had feared and Lincoln had anticipated. The Union would not be preserved by negotiations. It would be remade by force. The compromise remains a quiet monument to the last great effort to save the Union by reason rather than by war. It stands like a lonely milestone on a long abandoned road, marking the end of a tradition and the beginning of something harsher.

In that sense, the Crittenden Compromise is more than a political failure. It is a farewell to an age when Americans believed that every crisis could be solved with another careful arrangement. It reminds us that a country can reach a moment when its internal contradictions become too large to paper over. It warns that even honest and well meaning proposals cannot rescue a nation that has already decided to become something else.

And perhaps most striking of all, it shows us that peace is not always lost in a dramatic moment. Sometimes peace is lost quietly, in committee rooms, in abstentions, in letters sent from Springfield that tell allies to hold firm. Sometimes peace slips away while the world waits for someone to fix it.

That is why the story of the Crittenden Compromise still matters. It is not only the story of a plan that failed. It is the story of a nation discovering that the road behind it had collapsed, and the road ahead would demand a cost that no one wished to pay, yet everyone would soon bear.

Leave a comment