The ice cream cone is a small, crunchy piece of confidence. It is what a child chooses when a paper cup feels too ordinary and a bowl feels like homework. It is also, if we are being honest, an edible promise that you will handle your responsibilities. You will not spill. You will not drip down your wrist. You will not lose control of the situation in public. A cone is an optimistic contract between gravity and human dignity, signed in sugar and immediately challenged by summer heat.

It is everywhere now. It sits on road signs and tourist magnets. It is shorthand for carefree America, for boardwalks and ballgames and those brief moments when a grown man can eat something sticky without pretending it is a business lunch. That familiarity makes people assume it has always existed, or at least that it arrived the way folk tales say it did, in one clean moment of bright improvisation at the 1904 St. Louis World’s Fair. The story usually goes like this. It is hot. The crowds are enormous. An ice cream vendor runs out of dishes. A nearby waffle seller rolls a hot wafer into a cone, drops in the ice cream, and history politely applauds.

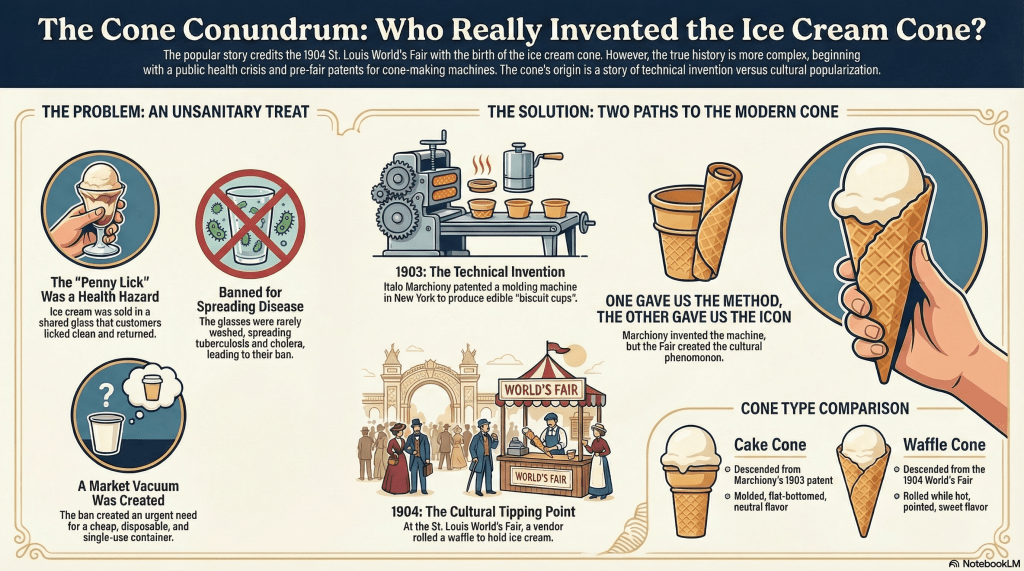

That story is not entirely wrong, but it is too tidy to be trusted. The cone did not begin as a cute idea. It began as a solution to a public health problem, a street vending crisis, and a blunt little economic reality. People liked ice cream. Vendors needed speed and profit. Cities were getting crowded and nervous about disease. The old serving methods were unsanitary, sometimes illegal, and always fragile. The ice cream cone was not a single eureka moment. It was a convergence of hygiene, hustle, and heat, plus patents, rival claims, and the kind of human memory that gets sharper when money is involved.

What The frock – The Musical

To understand why the cone mattered, you have to start in the unglamorous world of late nineteenth century street food, where ice cream was sold in ways that would make a modern health inspector faint and reach for a pen. In London and other cities, the penny lick was common. It was a thick glass with a shallow depression at the top. The thickness of the glass made the serving look larger than it was, which was its own quiet scam, but the real issue was what happened next. A customer paid a penny, licked the ice cream clean, handed the glass back, and walked away. The vendor reused it immediately, often without washing. In crowded neighborhoods, the same glass could pass from mouth to mouth all afternoon.

This was the age of cholera scares and tuberculosis dread, when cities were learning, painfully and slowly, that microbes did not care about class or charm. Public health officials looked at penny licks and saw a disease delivery system disguised as dessert. Ice cream itself became suspect, not because it was inherently dangerous, but because it was being served in a way that invited trouble. By the end of the nineteenth century, medical authorities were openly blaming shared ice cream glasses for spreading disease.

London eventually banned penny licks outright, explicitly tied to fears of cholera and tuberculosis. Other cities followed more slowly, but the direction was set. Street vendors needed a disposable serving method. Paper helped, but paper was a compromise. It solved sanitation but not satisfaction. It was soggy, flavorless, and wasteful. People accepted it because the alternative was worse, not because it was good.

Italian immigrant vendors were among the first to push past that compromise. Many sold flavored ices under the name hokey pokey, often wrapped in paper. The phrase likely came from the Italian ecco un poco, meaning here is a little, filtered through accents and street calls until it became urban slang. What mattered was not the name, but the direction. Frozen desserts were becoming portable and disposable, and once that door opened, the question followed naturally. If the container had to be thrown away anyway, why not make it edible.

The idea itself was not radical. It had existed for decades, quietly waiting for a way to escape the parlor and enter the street. In the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, European cafés occasionally served ice cream in wafer-like shells. An early nineteenth century French etching appears to show a woman holding a cone-shaped wafer filled with ice cream. It is suggestive but inconclusive, proof of concept rather than proof of practice.

A clearer step came in 1888, when Agnes Bertha Marshall published a recipe for what she called “cornets with cream.” These were edible cones made of flour, sugar, almonds, and eggs, baked and shaped around molds. They were elegant, refined, and utterly impractical for street vending. Marshall provided the idea in culinary form, but not the means to produce it cheaply or quickly. Her cones belonged to dining rooms, not sidewalks.

What transformed the idea into a viable product was machinery. In 1902, Antonio Valvona, an Italian immigrant living in Manchester, patented an apparatus for baking biscuit cups for ice cream. His design described a method for producing small edible containers in quantity. These were not rolled cones, but they mattered because they crossed a threshold. Ice cream containers were no longer handmade novelties. They were industrial products.

In 1903, Italo Marchiony took the next step in New York City. Marchiony sold lemon ice from a pushcart near Wall Street. Like every vendor using glass cups, he lost them constantly. Customers walked off with them. Children dropped them. Replacements ate into his profits. His solution was mechanical. He patented a molding apparatus that produced small biscuit cups, sometimes with tiny handles, formed in molds rather than rolled by hand. These cups could be baked, stacked, and sold cheaply. This design became the ancestor of what Americans now call the cake cone.

Marchiony’s invention solved several problems at once. It eliminated shared glass. It reduced theft. It lowered costs. It allowed production beyond the limits of one cart and one pair of hands. He later defended his patent in court and won. Technically, his claim was strong. Culturally, it never quite caught fire.

That distinction matters, because invention and adoption are not the same thing. A molded cup works. A rolled cone captures the imagination. The story of how that happened runs through St. Louis in the summer of 1904.

The Louisiana Purchase Exposition was enormous, crowded, and punishingly hot. Nearly twenty million visitors passed through its gates. The Pike was loud, commercial, and relentless. It was also a product of its time, steeped in imperial confidence and racial hierarchy, with ethnological exhibits that turned human beings into spectacles. This was not a gentle setting. It was a marketplace under pressure, where vendors competed fiercely for attention and money.

Ice cream sold fast in that heat. Vendors needed speed. They needed containers. Somewhere along that line, rolled waffle cones became ubiquitous. According to multiple contemporary accounts, Ernest Hamwi, a Syrian immigrant selling thin wafer pastries called zalabia, rolled his hot wafers into cone shapes and paired them with ice cream. Whether he was responding to a shortage of dishes or simply seizing an opportunity is unclear. What is clear is that the idea spread rapidly. Other vendors purchased rolled waffles by the stack and sold them as cornucopias.

Hamwi later built a business around ice cream cones, working as a salesman and eventually founding his own company. Abe Doumar, another immigrant from the same region, later claimed that he suggested the idea and improved it with a four-iron waffle machine that allowed faster production. His shop in Norfolk, Virginia still operates today, a living fossil of early cone technology.

They were not alone. Other families and vendors told similar stories. Names surfaced years later, often when money and reputation were at stake. The chaos of attribution tells its own story. This was not a single invention moment. It was a convergence under pressure, where multiple people recognized the same solution at the same time.

What the St. Louis fair really did was provide scale and visibility. It introduced the rolled waffle cone to millions of people in a setting designed to celebrate novelty. It turned a practical solution into an icon. The fair did not invent the cone in the patent sense. It popularized it in the cultural sense.

After the fair, demand surged. Hand rolling cones was possible but inefficient. It required skill, speed, and tolerance for heat. If cones were going to become a cheap, standardized product, they needed automation.

In 1912, Frederick Bruckman perfected a machine that could mold, bake, and trim cones automatically. This was the moment when cones became commodities. Production expanded dramatically. By the late 1920s, major corporations had entered the business. When Nabisco acquired Bruckman’s company, the cone became part of a national manufacturing system.

Immigrant entrepreneurship remained central even as corporations moved in. Companies like Joy Cone began with hand-operated ovens and grew steadily, turning family operations into industrial producers. The cone industry followed a familiar American pattern, small beginnings, long hours, gradual expansion, and eventual consolidation.

One problem remained. Cones and melting ice cream are natural enemies. A cone is crisp until it meets time. To sell pre-filled cones, someone had to solve the sogginess problem. In 1928, that solution arrived in the form of a chocolate-lined cone, later known as the Drumstick. By coating the inside of the cone with chocolate, manufacturers created a moisture barrier that allowed cones to be filled, frozen, shipped, and sold without collapsing. It was not romantic. It was effective.

By the mid twentieth century, the cone had settled into recognizable forms. The waffle cone, rolled, sweet, and aromatic, descended from the fairground cornucopia. The cake cone, molded and flat-bottomed, traced its lineage back to Marchiony’s patent. The sugar cone bridged the two, rolled but denser, harder, and sturdier. Each carried a piece of the past in its structure.

The cone replaced something unsanitary and unsustainable. It changed how Americans consumed ice cream. A bowl suggests sitting. A cone suggests movement. It turned dessert into something public and portable. It matched the rhythm of modern life without asking permission.

This is why the story matters, even now. The ice cream cone is a case study in how innovation actually happens. It emerges from pressure, regulation, and necessity. It is shaped by immigrants adapting old skills to new conditions. It spreads when culture, commerce, and practicality align.

Missouri eventually declared the ice cream cone its official state dessert. That gesture is symbolic rather than technical, but symbolism has always been part of the cone’s power. St. Louis may not own the patent, but it helped give the cone its moment.

So who invented the ice cream cone. The honest answer depends on what you mean by invention. Valvona and Marchiony built the machinery and claimed the technical ground. Hamwi, Doumar, and the fairground vendors gave the cone its shape, its popularity, and its place in memory. One group created the method. The other created the icon.

The cone you hold today is the product of both. It is not a miracle. It is batter, iron, heat, and the refusal to keep doing things the old, dirty way. That is how most lasting inventions arrive, quietly practical, born of necessity, and sweetened just enough for the public to accept them without asking too many questions.

Leave a comment