There is a particular corner of Japanese history where the past still feels alive. It is quiet, disciplined, and cold around the edges. Every December, when the year is wearing thin, people gather at a small temple in Tokyo. They burn incense and bow before a row of graves. These stones belong to men who are long dead, yet their story has managed to outlive entire dynasties and ideologies. The world calls them the Forty Seven Ronin. Japan calls them gishi, men of righteousness. Historians call them something else, something harder to pin down. They stand at the crossroads of fact and legend, a place where accuracy and imagination shake hands and agree not to fight about it. The story opens in the year 1701, in Edo Castle, where a lord lost his temper, a bureaucrat lost some skin, and the shogun lost all patience. That moment set in motion a tale of honor, grief, loyalty, and vengeance that refuses to fade away, no matter how many centuries drift past.

The Genroku era was a time of peace for Japan. The great battles of the Sengoku age were long over. Samurai still wore their swords, but most spent their days behind desks rather than on horseback. They managed rice taxes, water canals, and family disputes. They studied Confucian philosophy. They copied legal codes. They recited poetry with varying degrees of talent. The sword remained, but the world had become quieter, more structured, and much more regulated. This was the Tokugawa order. The shogun governed through an elaborate bureaucracy that prized hierarchy and etiquette to a degree that would make a royal protocol officer in London sweat with envy.

Into this world stepped Asano Naganori, the young lord of Ako. His title was Takumi no Kami, an elegant name that suggested refinement. His reputation was less consistent. Some sources paint him as earnest, upright, and a little stiff. Others quietly hint that he was out of his depth at court, a provincial lord trying to swim in waters populated by sharks who wore silk and smiled politely. In Edo Castle he found himself under the instruction of Kira Yoshinaka, the Master of Ceremonies. Kira was no mere usher. He was a highly placed official, responsible for the smooth running of rituals that mattered deeply in a society built on formality. History has often played him as the villain, the sneering courtier who demanded bribes from Asano and insulted him when he refused. Yet contemporary documents do not support this melodrama. Kira was respected in his own domain. He had a solid administrative record. His reputation was not that of a thug but of a man who knew exactly how the court expected things to be done.

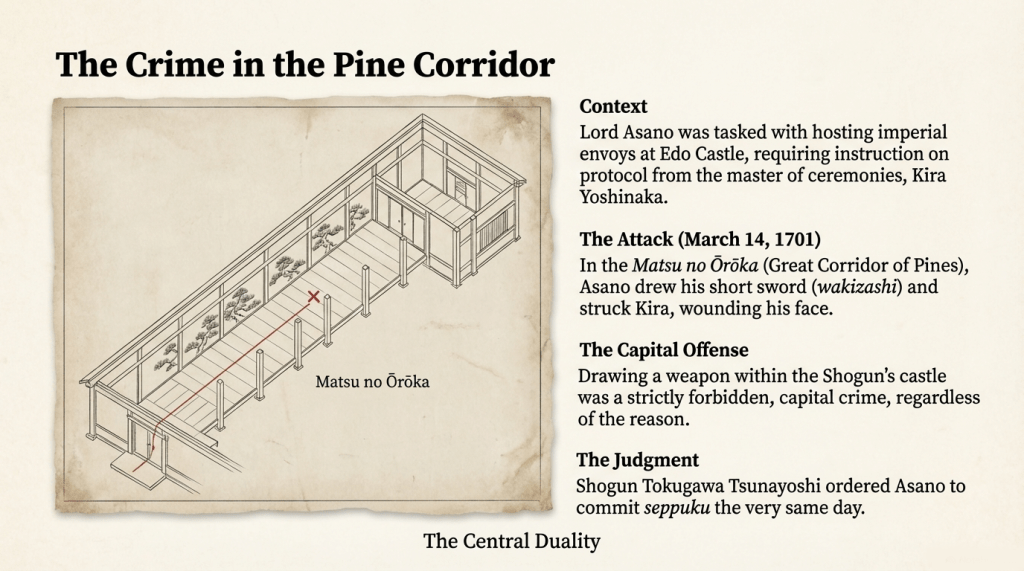

Still, two men can be perfectly respectable and entirely incompatible. Asano needed Kira to guide him through the complex etiquette required to host imperial envoys from Kyoto. The assignment was an honor, but also a minefield. One mistake could embarrass the shogun himself. Tensions rose. Perhaps Asano bristled under correction. Perhaps Kira found Asano slow to learn. Perhaps there were slights imagined, slights real, or slights that grew larger every time they were repeated in the quiet corners of the castle. Some storytellers insist that Kira demanded gifts and became angry when he did not receive them. The legend often brings in another lord, Kamei, who supposedly avoided Asano’s fate only because his retainers quietly paid Kira a generous sum. It is a good story. It carries that familiar scent of a moral universe in which greed leads to downfall. Unfortunately, good stories are not always good evidence. There is no contemporary confirmation of these bribes. If they happened, no one wrote it down where we can find it. The conflict between Asano and Kira may have sprung not from corruption but from a simple clash of temperament and protocol.

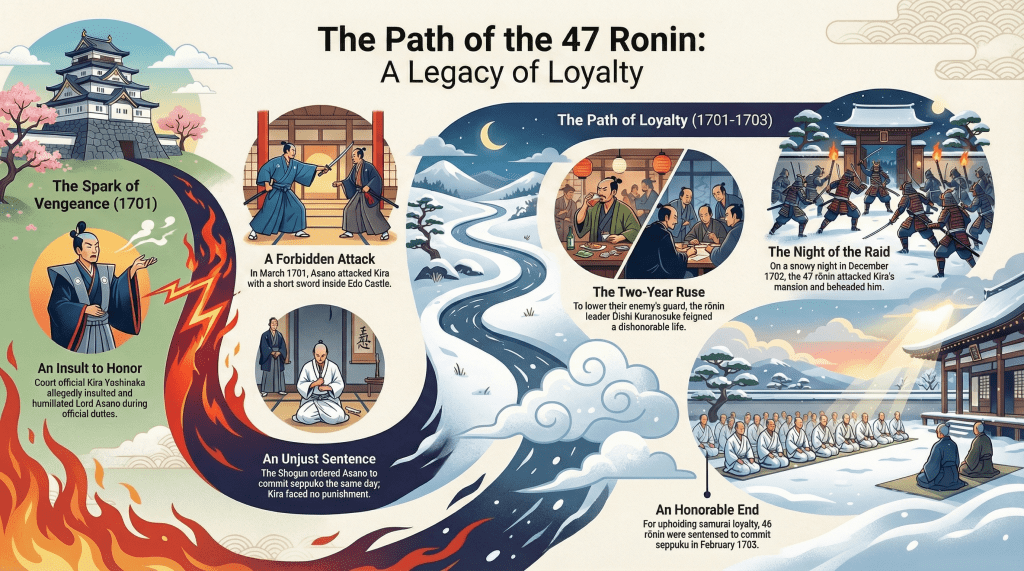

On March 14, 1701, Asano’s patience finally broke. In the Pine Corridor of Edo Castle, he drew his wakizashi and struck Kira. It was a wild act, the sort of thing one sees in plays rather than in a government building. He wounded Kira but did not kill him. That failure sealed the matter. Drawing a weapon inside the shogun’s castle was considered a direct assault on the shogun’s authority. It was treason of the simplest, least poetic kind. Asano was ordered to commit seppuku the same day. No appeal, no pause, no chance to explain himself. His domain was confiscated. His family was ruined. Kira received no punishment, a fact that outraged Asano’s retainers. There was a customary rule known as kenka ryoseibai, which held that both parties in a fight were to be punished. Asano struck Kira, yet only Asano paid the price. This imbalance became the moral core of the events that followed. Even a peaceful era can tolerate only so much inconsistency before something snaps.

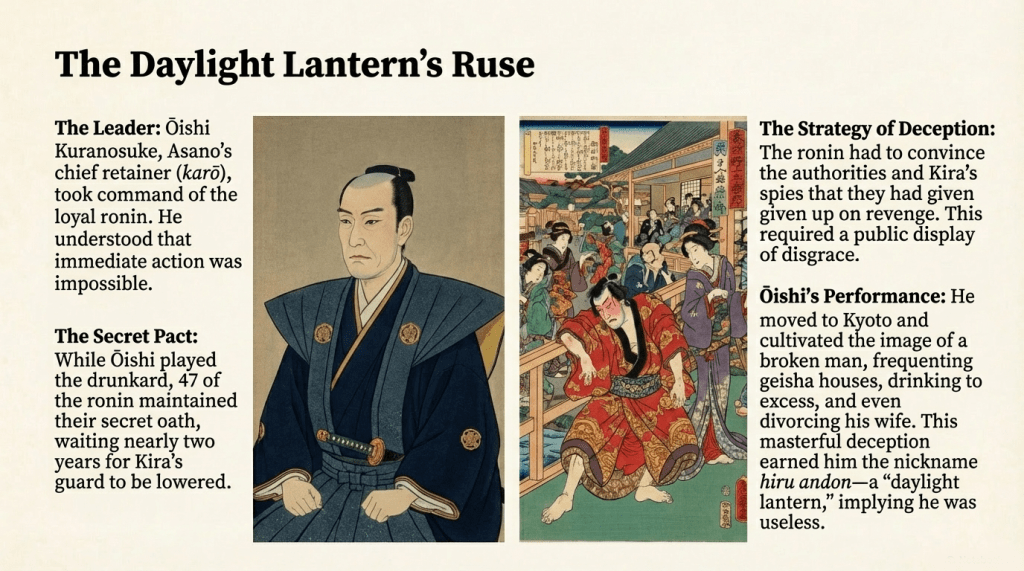

Asano’s samurai found themselves suddenly without a master. They became ronin, wandering men, men cut loose from purpose and identity. Their chief retainer was Oishi Kuranosuke, a man whose calm exterior masked a keen strategic mind. He understood the political terrain better than most. If the ronin struck too soon, the shogunate would crush them. If they did nothing, the world would forget their lord, and they would live the rest of their lives as relics of a failure that was not entirely theirs. They needed time, and they needed Kira to believe that they were broken, disorganized, and harmless. Oishi began a performance that would make even the most dedicated method actor raise an eyebrow. He abandoned himself to drink and pleasure houses in Kyoto. He staggered through the city, drunk at midday, laughing too loudly, letting rumors paint him as a washed up fool who had wasted his loyalty on an unworthy cause. He divorced his wife, a heartbreaking decision that still stands as one of the quiet tragedies behind the louder tale.

People called him a daylight lantern, a thing that gives no light where it is most needed. In this case, the insult served his purpose. Kira’s spies reported that the Ako men had scattered. Some took up trades. Some pretended to quarrel. A number of them sank so deeply into their disguises that one wonders how they kept their courage intact. Beneath it all, they met in secret, swore an oath, and waited. Seasons passed. Snow fell. Cherry blossoms came and went. The shogunate relaxed its attention. Kira let his guard drift lower. Oishi watched. That was what he had been waiting for.

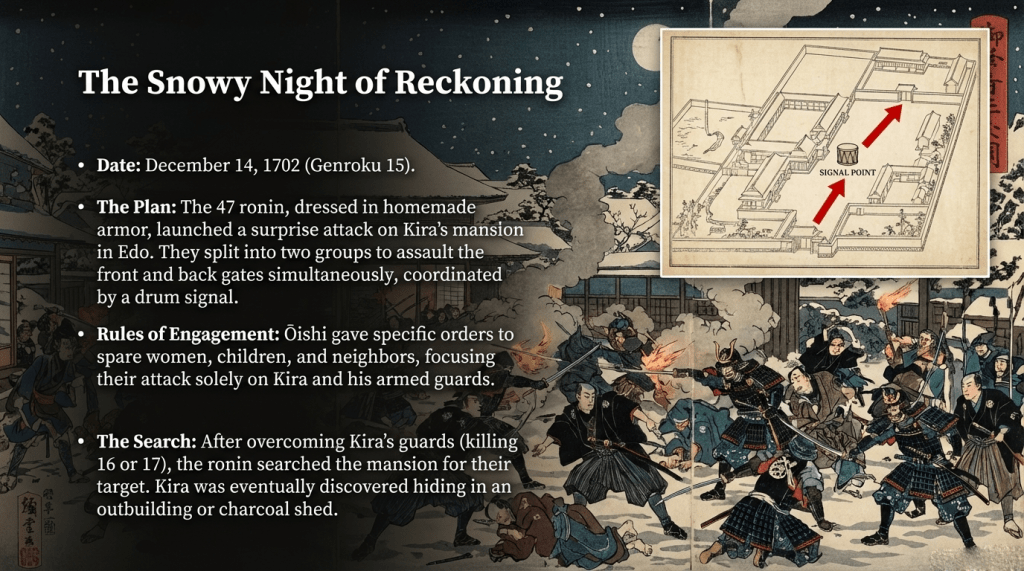

On a cold night in December 1702, the Forty Seven Ronin assembled in Edo. They wore simple armor of their own making. They split into two groups and moved toward Kira’s mansion. The snow muffled their footsteps. A drum signaled the beginning of the attack. Neighbors were told to stay indoors. Women inside the mansion were spared, a detail that appears again and again in retellings, perhaps because it promises that even revenge can be tempered with restraint. The fighting was fierce. The ronin killed more than a dozen guards as they searched the house. They could not find Kira until someone noticed a shed that looked more like an outhouse than a hiding place. There, clutching a bundle, was a man whose forehead bore a scar from Asano’s blade.

Oishi offered Kira a chance to die honorably. He presented Asano’s dagger, the same weapon used in the ritual seppuku. It was a gesture of respect and judgment at the same time. Kira could not bring himself to use it. Oishi ended the matter with a single stroke. The ronin then walked across Edo to Sengaku ji Temple. They carried Kira’s head, washed it in the temple well, and placed it on Asano’s grave. Their vigil that night has been described in countless poems, some more successful than others. The worst poem in the universe would likely have attempted to rhyme something with “Kuranosuke” and would have deserved the ridicule it received. Fortunately, the ronin themselves wrote no such verses. They left the scene with dignity.

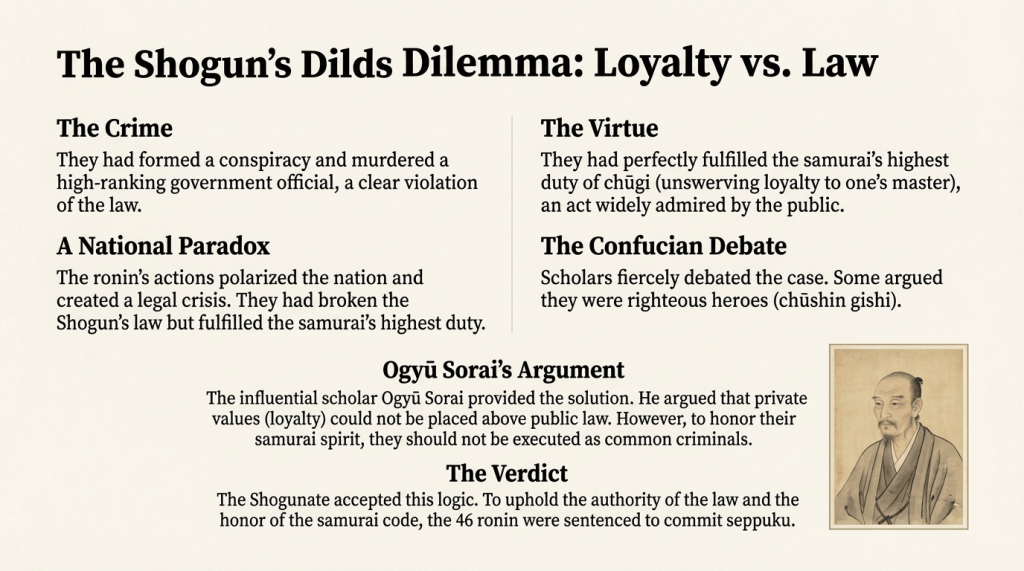

Their actions created a legal puzzle that would have tested any government. The ronin had committed murder in an organized, deliberate fashion. They had stormed a private residence, killed its defenders, and taken the head of a shogunate official. At the same time, they had acted out of loyalty, a virtue Japan prized deeply. The public sympathized with them. Crowds gathered outside the mansions where they awaited judgment. Confucian scholars debated their fate. Some argued that they were perfect models of duty. Others pointed out that if every samurai acted on private vendettas, the entire legal structure would collapse.

Ogyu Sorai, one of the most influential thinkers of the time, took a position that still feels wise in its own stern way. He argued that the ronin could be honored for their loyalty, but the law must remain the final authority. If the shogunate allowed the ronin to go free, it would invite chaos. If the shogunate executed them like criminals, it would insult the very ideals it claimed to uphold. Sorai recommended that they be ordered to commit seppuku. They would die as samurai, not as felons. The shogun accepted this approach. On February 4, 1703, the remaining forty six ronin performed ritual suicide. They were buried beside their master at Sengaku ji. Visitors today still leave incense and flowers, proving that memory can be more durable than stone.

The forty seventh ronin, Terasaka Kichiemon, survived. He had been sent away before the raid, perhaps to act as a messenger. He was eventually pardoned. He lived into old age, long enough to see the legend begin to take form. His survival complicates the story, as survivors often do. Grand narratives prefer clean endings. Real life is rarely so tidy.

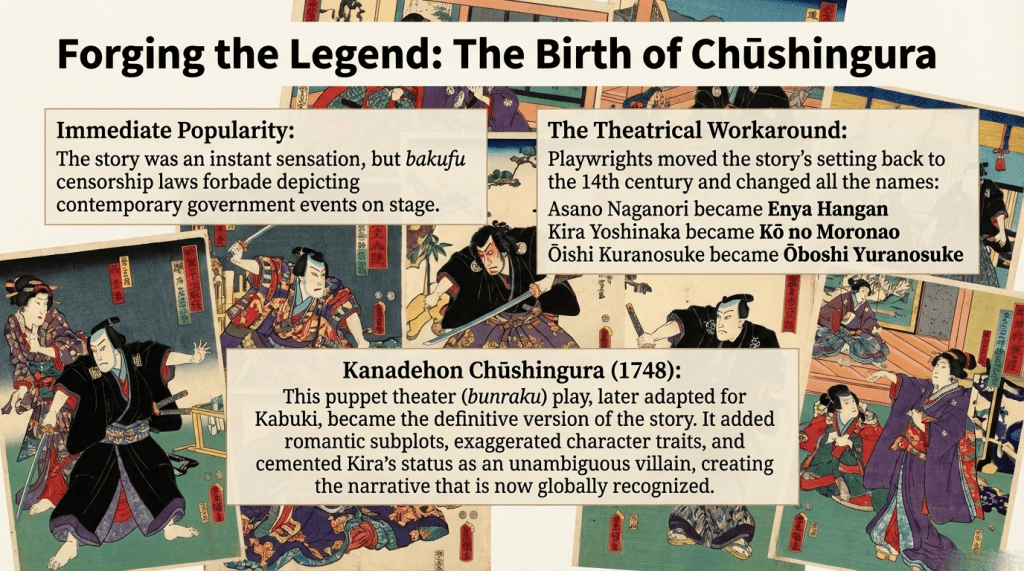

Within decades, censorship laws shaped the narrative into something new. The shogunate forbade dramatizations of current political events, so playwrights hid the story inside a historical disguise. In 1748, the puppet theater produced Kanadehon Chushingura, The Treasury of Loyal Retainers. Names were changed. Asano became Enya Hangan. Kira became Ko no Moronao. Oishi became Yuranosuke. The skeleton of the story remained, while theatrical embellishments filled in the emotional and dramatic gaps. Romantic subplots were added. Villainy became more blatant. The forty seven were transformed from strategic avengers into mythic heroes guided by destiny. Kabuki actors specialized in these roles, striking poses that art critics still admire.

The visual arts embraced the tale as well. Ukiyo e masters produced entire series depicting the ronin in moments of action, contemplation, or heroic resolve. Kuniyoshi in particular seemed to revel in presenting each man as a distinct personality drawn in bold lines and rich color. These prints helped cement the legend in the public imagination. When photography arrived, prints continued to outsell portraits. One cannot help but think of Douglas Adams and his observation that reality is often inaccurate. The prints did not show the men as they were, but as the public wished to remember them, and that was enough to sustain the legend’s momentum.

Film gave the tale a new medium. Japan produced dozens of versions, including a 1941 production that treated the ronin as propaganda symbols of national loyalty. A 1962 film remains a classic, restrained, elegant, and deeply respectful. The 2013 Hollywood adaptation, which added demons and magic, took more liberties than a storyteller probably should. It proved that even legends are not safe from the creative impulses of modern studios. If the ronin had anything to say about that version, they would likely sigh, straighten their armor, and walk away without comment, which is the most devastating critique of all.

Not everyone admired the ronin. Yamamoto Tsunetomo, author of the Hagakure, believed they had waited too long. To him, true samurai should have attacked immediately. Hesitation was worse than death. His position has the clarity of a rule book, yet it misses something human. The ronin may have understood that dying quickly is easy to romanticize, while living with purpose is harder. Their choice was not impulsive. It was patient, deliberate, and grounded in the realities of the Tokugawa political system. Other critics argue that the ronin perpetuated a culture of violence masked as virtue. There is truth there as well. The story lives in the tension between these viewpoints.

The Meiji Restoration transformed Japan into a modern state, and in that transformation the ronin found new life. They were held up as symbols of loyalty to the emperor. During the Second World War, their story was employed to reinforce ideals of sacrifice. Soldiers marched with the ronin in mind. Propaganda offices reproduced Chushingura scenes in pamphlets. Legends tend to get repurposed by those who need them. The Forty Seven Ronin became a cultural mirror reflecting whatever value the age wanted to see. That flexibility helps explain their longevity.

Today, Sengaku ji remains a place of pilgrimage. Visitors come year round, but December 14 draws the largest crowds. People light incense. They walk slowly past the graves. They whisper prayers or simply stand in silence. No one has to explain the story to them. The stones do the talking. They remind us that loyalty, sacrifice, and justice are ideas that refuse to retire quietly into the archives. They continue to tug at the human imagination, even in an age of neon lights and digital noise.

Modern viewers who encounter the story through films or prints may feel an instinct to search for a moral. There is comfort in tidy lessons. Yet the Forty Seven Ronin resist that simplicity. Their actions were noble to some, reckless to others, and deeply unsettling to anyone who prefers the rule of law over vendetta. The story does not settle the debate. It simply presents the events and leaves the reader to wrestle with them. A seasoned historian can appreciate that. History rarely offers clarity. It offers instead a collection of moments where people made choices under pressure, armed with imperfect information and very human fears.

The tale of the Forty Seven Ronin matters today because it bridges the gap between duty and emotion. It asks whether loyalty can be both destructive and beautiful. It asks whether justice should be legal or moral when the two collide. It asks whether a society built on order can survive the weight of its own contradictions. For all the centuries that separate us from the Genroku era, these questions still wander through our modern lives like half remembered ghosts.

If you visit Sengaku ji on a winter morning, you will see curls of incense smoke drifting upward. They twist softly as if the air itself is remembering something. People bow before the graves. Some bring notes. Some bring offerings. Some simply stand there and breathe in the ancient quiet. The graves do not answer, yet the silence feels full. The ronin have been dead for more than three hundred years, but through ritual, storytelling, and the stubborn persistence of memory, they remain present. They remind us that honor can both inspire and trouble us, that loyalty is both a virtue and a weight, and that history is often less concerned with correctness than with consequence.

The Forty Seven Ronin live on because their story captures a devotion that was not commanded from above. It rose from within. It was messy, imperfect, and far from the crystalline virtues that legends pretend to preserve. It was human. That is why it endures. Long after the incense burns out, long after visitors return to their own hurried century, the smoke still rises in the mind, carrying with it the faint echo of footsteps crunching through snow toward a house where justice waited patiently in the dark.

Leave a comment