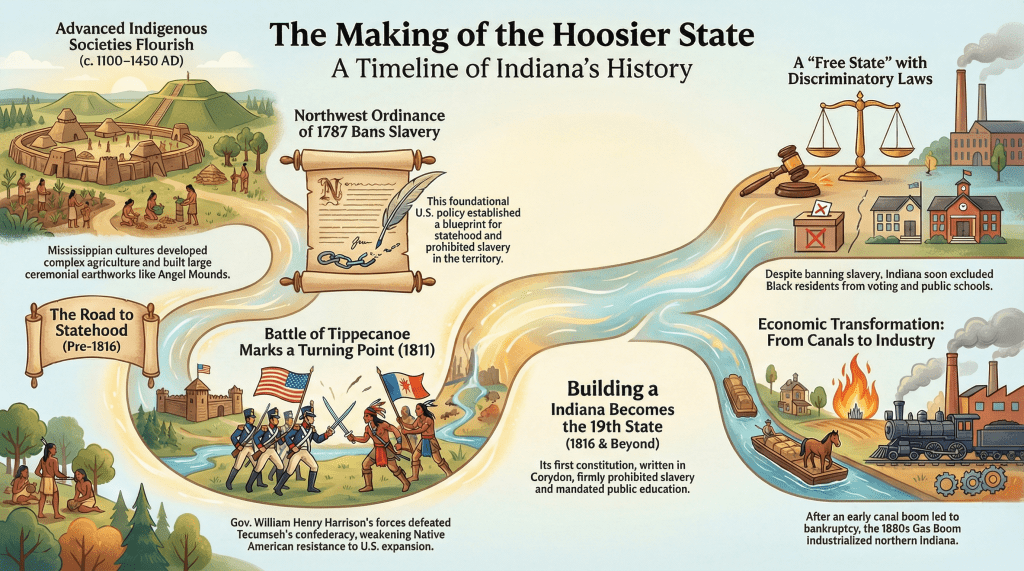

Indiana’s story begins long before it had a name, which is usually how these things go. The land that would one day become the nineteenth state sat quietly for thousands of years, shaped by ice, wind, and rivers that wandered like indecisive travelers. Human beings eventually arrived and did what human beings always do. They adapted, built lives, invented tools, and left behind traces that modern people study while admitting privately that the ancients probably understood more than we give them credit for. Indiana’s earliest inhabitants were Paleo Indians followed by the Archaic peoples who hunted, fished, and gathered across a landscape that did not care what anyone called it. Later cultures like the Adena and the Hopewell built mounds that still rise from the earth with a kind of patient confidence. The Mississippian world grew maize in broad fields and built ceremonial centers that whispered of order and cosmic meaning. Angel Mounds, near what is now Evansville, remains as stubborn proof that these societies were not drifting in darkness. They understood their world as clearly as we understand ours, which is to say imperfectly.

Before European flags came marching across maps, the region was home to the Miami, the Shawnee, the Potawatomi, and others who managed alliances, rivalries, and trade networks with an ease modern diplomats might admire if they were not so busy misunderstanding each other on cable news. The Beaver Wars raged for control of the lucrative fur trade. The Iroquois pushed hard. The Algonquian tribes pushed back. The result was depopulation, a grim pause in the human rhythm of the place, a silence that set the stage for the next wave of newcomers who believed that unexplored land simply meant no one important had noticed it yet.

The French were the first Europeans to lay claim, and they did it with the kind of bold confidence that comes from believing the world exists primarily for the purpose of being claimed. René Robert Cavelier, Sieur de La Salle arrived in 1679, looked around, and said in effect, this belongs to Louis XIV now. French traders moved in along the rivers, built small posts, and treated Indiana as an extension of their commercial empire. Fort Vincennes, established in the 1730s, was the only settlement to truly endure. The French presence was rarely overwhelming, more of a long conversation between peoples who understood furs, river routes, and the unspoken rules of frontier diplomacy. But empires have a way of knocking into each other like ships on a crowded lake. By the time the Seven Years War ended, the British had taken Indiana without ever really knowing what to do with it.

When the American Revolution began, Indiana was a distant idea in the minds of the people fighting on the eastern seaboard. Yet the war reached deep into the interior. George Rogers Clark marched into the Illinois country and captured Vincennes in 1779, taking British Lieutenant Governor Henry Hamilton prisoner in a move that felt improbable even then. Clark later remarked that his men had “behaved like men,” which is the sort of understated compliment one gives when the truth sounds too dramatic to be believed. The Treaty of Paris in 1783 ceded the region to the United States, and the new nation inherited a vast territory that it did not entirely understand.

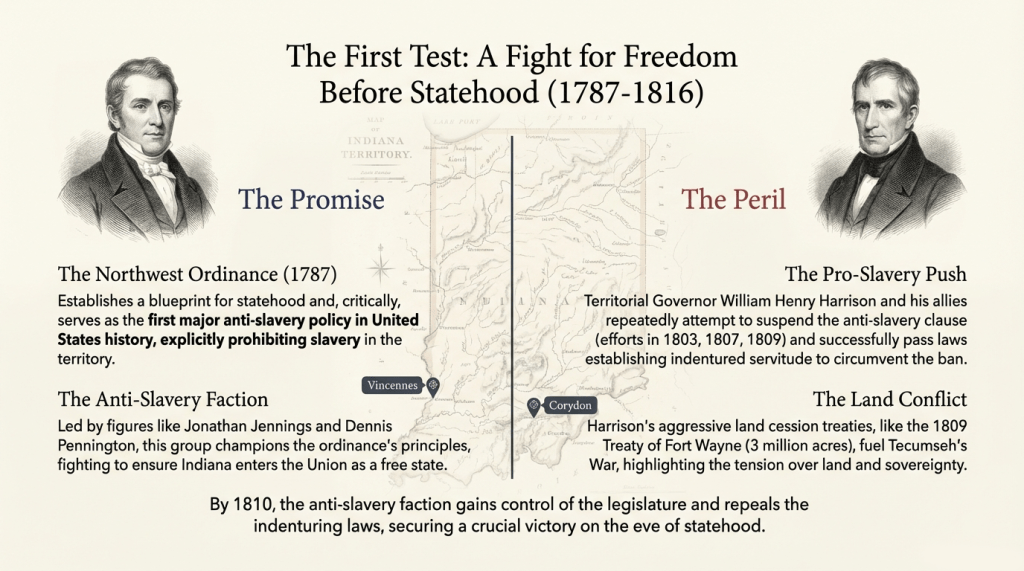

The Northwest Ordinance of 1787 created a political framework for this enormous land. It said that the United States would expand not by colonizing subjects but by raising new states equal to the original ones. It said something else too. It outlawed slavery in the Northwest Territory. It was an early attempt at drawing a line in a country that still staggered under the weight of its own contradictions. Indiana Territory was carved out in 1800 with its capital at Vincennes. William Henry Harrison, a young man with aristocratic leanings and considerable ambition, became the first territorial governor. He approached Indiana as a place that might someday reflect his own vision of political and economic order.

Not everyone agreed with what that order should look like. The first major struggle in territorial politics revolved around slavery. Harrison and his allies believed that suspending the Northwest Ordinance’s antislavery clause would attract settlers from the South who would build farms and communities more quickly. They petitioned Congress again and again for permission. They wrote laws that disguised slavery behind the polite term indenture. Their opponents, led by men like Jonathan Jennings and Dennis Pennington, said that a free territory ought to mean exactly what it said on the parchment. They fought Harrison in the legislature and eventually gained enough power to repeal the pro slavery measures. They were not perfect men and their motives were not entirely pure, but they held the line when it mattered. By 1810, the effort to make Indiana a slave territory was all but dead.

Conflict with Native nations escalated sharply during this same period. Harrison negotiated land treaties like a man fulfilling a cosmic checklist. The Treaty of Fort Wayne in 1809 handed over more than three million acres. Tecumseh, the Shawnee leader, stood up and said plainly that no single tribe could sign away land that belonged to all. His brother Tenskwatawa inspired a broader movement toward Native unity. The Americans saw this as defiance that needed to be crushed. The resulting conflict, Tecumseh’s War, ended without Tecumseh present. Harrison marched to Prophetstown and the Battle of Tippecanoe left the settlement in ruins. American newspapers celebrated the victory. The Wabash Valley filled with smoke and ash. Tecumseh rebuilt his coalition and joined the British in the War of 1812, a desperate gamble that ended with his death in 1813.

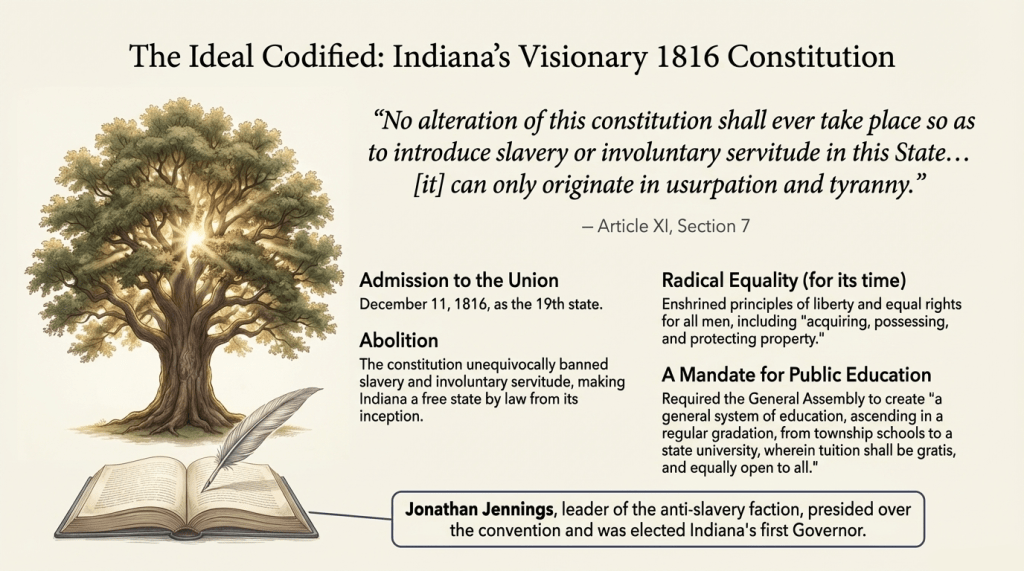

By 1816 the population of Indiana Territory had passed sixty thousand. Congress approved statehood under an Enabling Act. Delegates gathered in Corydon in June to write a constitution. The room grew hot, so they moved outside to the shade of a giant elm, which history now remembers as the Constitution Elm. The tree has long since died, but the stump remains preserved under a sandstone dome, a reminder that great documents are often drafted in less than majestic circumstances. Jonathan Jennings presided over the convention. He was a sharp, persistent politician whose private struggles sometimes troubled his public image. Yet he believed that Indiana should enter the Union as a free state that offered educational opportunity and placed real limits on executive power. Dennis Pennington, the stonemason who helped build the Corydon capitol, pushed for transparency and fairness. These men and others wrote a constitution that promised trial by jury, religious liberty, and, in language that felt deliberately firm, declared that slavery could not exist in Indiana. They instructed future lawmakers to create a system of free public education open to all, a promise that would take generations to fulfill.

On December 11, 1816, President James Madison signed the act admitting Indiana as the nineteenth state. For a moment the story could have ended in celebration and triumphal certainty. But this is history, not theater. The new state faced financial troubles, unresolved conflicts, and the complicated reality that ideals and behavior rarely travel together.

Indiana’s early years were marked by legal battles over the remnants of slavery. In cases like Polly v. Lasselle and Mary Clark v. Johnston, the Indiana Supreme Court stated plainly that every person in Indiana must be free. These rulings closed the loopholes that pro slavery forces had used. Yet even as the law established freedom, the state passed discriminatory measures against Black residents. They could not vote or testify against white citizens. A cruel 1831 statute required any Black person entering the state to post a five hundred dollar bond, which in practical terms meant that most could not come at all. Even ideals that look noble on paper can warp quickly when fear or prejudice finds the right political audience.

There were Hoosiers who resisted the injustice. Communities across the state became part of the Underground Railroad, helping enslaved people escape north. Levi Coffin, an Indiana Quaker, was so effective in this work that admirers called him the President of the Underground Railroad. This was not a title he sought. It was simply what happens when a man spends years helping strangers reach a freedom he believes they deserve.

The state also pursued a grand dream of internal improvements. Roads, canals, and turnpikes were meant to knit the frontier into a thriving economy. The National Road crossed into Indiana in 1829. The Wabash and Erie Canal began construction soon after. The state legislature borrowed heavily to fund these projects. They believed that progress required bold risk. By 1841 that risk looked less bold and more disastrous. The state teetered on bankruptcy and surrendered many of the unfinished projects to creditors. Ambition had run faster than prudence, which is a condition that Americans tend to rediscover every few generations. Out of this mess came political momentum for a new constitution adopted in 1851. It limited state debt and, in a gesture that reflected the prejudice of the time, barred new Black settlers entirely.

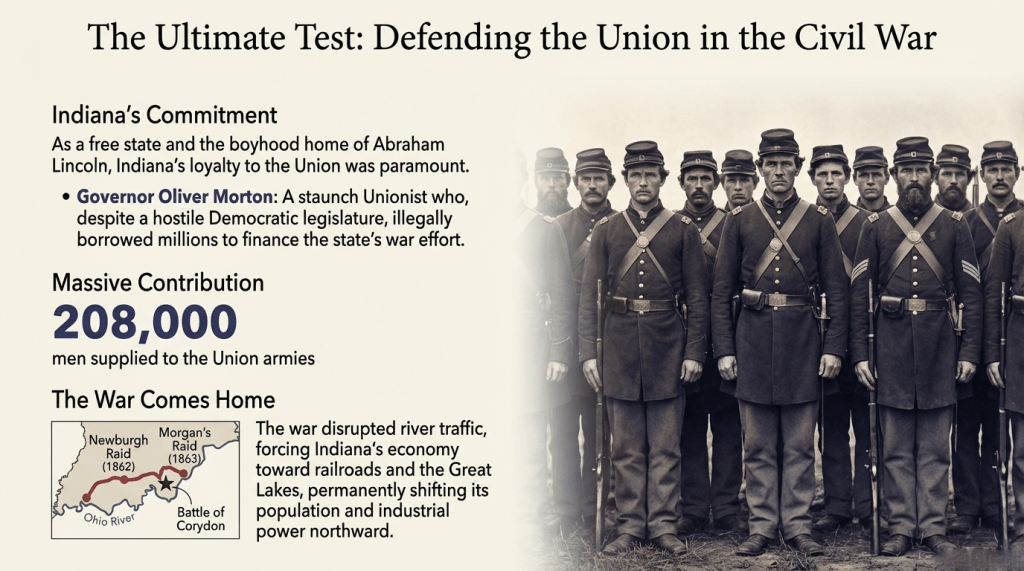

Indiana entered the Civil War with a divided political landscape. The governor, Oliver Morton, supported the Union with an intensity that bordered on obstinate. When the legislature refused to fund the war effort, Morton borrowed money privately to arm and supply Indiana regiments. He believed the survival of the Union mattered more than procedural niceties. Indiana sent more than two hundred thousand soldiers to the war*. Confederate raiders struck the state twice, once at Newburgh and once in Morgan’s Raid, which led to a skirmish at Corydon. After the war, economic and population centers shifted northward as railroads and Great Lakes commerce gained importance.

Industrialization arrived with its usual mix of promise and disruption. The Indiana Gas Boom in the 1880s fueled rapid growth. Factories produced glass, pharmaceuticals, and musical instruments. Elwood Haynes built an early automobile that looked like a cross between a carriage and an engineering experiment. Politically the state became a swing state, a place the national parties courted endlessly. Hoosier authors like Booth Tarkington and James Whitcomb Riley created what later generations would call a golden age in state literature. A warm sentimental fog sometimes surrounds this period, but it was a time of hard work, uneven progress, and no small amount of human struggle.

The Progressive Era brought reform and its opposite. The temperance movement gathered strength. The state adopted prohibition before the nation did. Women won the right to vote in 1920. Yet the same era saw the rapid rise of the Ku Klux Klan, which dug its claws deep into Indiana politics. The Klan boasted tens of thousands of members before collapsing after 1925 when its leader, D. C. Stephenson, was convicted of murder. His trial tore open the organization’s inner workings and left Indiana to confront the embarrassing fact that extremism is never as far from the surface as good people would like to believe.

The Great Depression hit Indiana with devastating force. Unemployment soared above twenty five percent. Governor Paul McNutt built a welfare system and introduced the state’s first income tax. Federal programs repaired roads, bridges, and public buildings. When World War II began, Indiana’s industries shifted into high gear. Evansville produced P 47 Thunderbolts. Almost four hundred thousand Hoosiers served in uniform. Some returned home to stable jobs and suburban dreams. Others watched factories decline in the decades that followed as global changes reshaped American manufacturing and placed Indiana squarely in what people began calling the Rust Belt.

The postwar period brought growth and loss in equal measure. Discriminatory housing practices like redlining carved deep wounds in Black neighborhoods, especially along Indiana Avenue in Indianapolis. The economy evolved slowly toward banking, healthcare, and technology. Agriculture remained a steady backbone. New factories produced electrical vehicles and batteries. Tornadoes and floods reminded Hoosiers that nature does not care about timelines or budgets. The state rebuilt each time because that is what communities do when they decide they still belong to one another.

Indiana’s history is not a straight line. It is a series of negotiations between ambition and restraint, hope and fear, exclusion and belonging. Its founding constitution insisted on liberty while its laws restricted Black settlement. Its early leaders fought hard for free education while leaving the task unfinished. Its people resisted slavery while enforcing discrimination. These contradictions are not unique to Indiana, but the state’s story reveals how ordinary people wrestle with ideals and consequences over long stretches of time. The land that began as a frontier outpost became a crossroads not because of clever branding but because so many currents of American life have passed through it.

The statehood process in 1816 marked the beginning of a long experiment in self government. It announced a belief in equality that the state has spent generations trying to honor more fully. When modern Hoosiers look back on that moment they might see not a triumphant arrival but an invitation to continue the work. The past, after all, is never finished. It waits quietly in the corners of statehouses, in the shadows of old elm trees, in the grain of courthouse steps worn down by people who had somewhere important to go. Indiana’s history lives in those details. It lives in the way the state has stumbled and recovered, forgotten and remembered, faltered and persisted. That is the story worth telling, the one that reminds us that a place becomes itself through the choices of many hands over many years. Indiana’s hands have shaped a state that is still finding its way and still determined to stand on its own feet in a world that rarely stands still.

*Among them, in the 40th Indiana, was one John George Bowman, my great-great-great grandfather

Leave a comment