There are moments in history when the noise of the present suddenly stops and the quiet truth of the future steps forward. Sometimes that truth arrives with a whisper and sometimes it arrives with the falling shadow of aircraft whose pilots have spent years training for the exact task at hand. On December 10, 1941, off the coast of Malaya, a British admiral who believed in the old order of things found out that the age of the battleship had died two generations earlier than he wished to admit. The obituary was written in the oil slick that spread across the South China Sea as HMS Prince of Wales and HMS Repulse slipped beneath the waves. It was an ending so stark and so final that even the most stubborn romantics of naval warfare had to accept that the world had changed. The sea was still the same. Human courage was still the same. The machines were not.

Force Z was supposed to be a symbol of British resolve. The Admiralty intended it to stand like a granite monument off Singapore, reminding any hostile observer that although the sun was setting on the British Empire, it still cast long shadows. Prince of Wales was modern, powerful, and fresh from the Atlantic triumph over Bismarck. Repulse was older, but fast, and commanded by a captain whose name would become forever tied to the impossible steering maneuvers that briefly kept her alive. They sailed with four destroyers, small dogs escorting two lions that had wandered into a hunting ground where every predator flew.

The world had already changed by the time these ships reached Singapore. Within seventy two hours of their sinking, the Pacific had transformed from a quiet strategic chessboard to a field of blows and counterblows. The attack on Pearl Harbor had shattered old assumptions. The Japanese invasion of Malaya was advancing with a speed that even seasoned British officers found difficult to comprehend. In that moment, Force Z should have been a warning that battleships unshielded by aircraft were relics, too slow to hide and too large to miss. Instead, they were sent out as if the clock could be wound backward.

Ever since the guns fell silent in 1918, British planners had built an entire strategic worldview around one idea. If the Empire ever faced a major threat in Asia, the main fleet would steam from Britain to Singapore, gather its strength, and keep the peace through the sort of credible menace that only steel hulls and heavy guns could provide. This Singapore Strategy looked tidy on paper. It echoed earlier eras when an empire could dispatch armored squadrons from the Home Fleet and expect the world to take note. It never accounted for the possibility that Britain might one day be fighting for its life in Europe while also trying to defend Asian colonies whose airfields and harbors were already under threat.

By late 1941, the Admiralty could not spare a full battle fleet. What it could spare was something smaller, leaner, and far less suited to deterring a modern opponent. Prince of Wales and Repulse were powerful in the traditional sense, but they were thrust into a climate whose humidity and heat did their machinery no favors. They carried anti aircraft ammunition that had deteriorated in storage. Prince of Wales carried a High Angle Control System radar that malfunctioned in the tropical environment. Several officers warned that the ships were not ready. Admiral Sir John Tovey went further, arguing that Prince of Wales was fundamentally unsuited to the region. Warnings spread outward like ripples that never quite reached decision makers who were still guided by the old faith in battleships.

Even the composition of the force carried symbolic weight. Prince of Wales represented the promise of modern naval architecture. Repulse represented an older era when agility and speed compensated for light armor. Together they were intended to signal seriousness. Instead, their pairing signaled desperation. This was the fleet Britain could assemble, not the fleet it wanted.

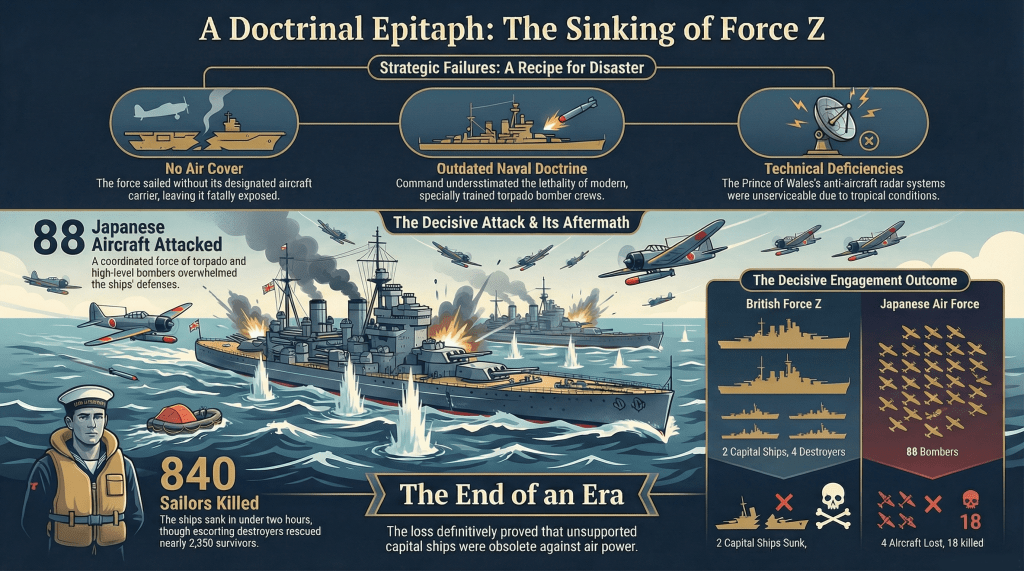

There was another missing piece. It was the one that would matter more than any other. Force Z had no air cover. There had been talk of assigning the carrier HMS Indomitable, but she was unavailable due to grounding damage and training needs. That single absence doomed the enterprise. RAAF and RNZAF planners had proposed a daylight cover plan called Get Mobile that would coordinate Allied fighters with the fleet, but this plan was dismissed by higher authority. In these moments before disaster, one sees how institutions fail. They do not collapse at once. They quietly push aside ideas that seem too new or too alien to established doctrine.

Into this setting stepped Vice Admiral Sir Tom Phillips. He commanded Force Z and went down with his flagship. Phillips had climbed the ranks through years when naval power meant something very specific. He distrusted the idea that aircraft could sink well handled battleships operating at sea. Perhaps that instinct came from an earlier era, one in which the worst adversary a battleship expected to face was another battleship. Phillips believed in secrecy and surprise. He therefore maintained strict radio silence even when it deprived him of timely air support. When history judges a commander, it often focuses on the moment their decision became fatal. Yet Phillips was operating within a system that had failed long before he set foot on Prince of Wales. Some historians call him a scapegoat. Others suggest he was simply the last believer in a religion that had already lost its gods.

While the British prepared for a show of traditional naval force, the Japanese had been training for something else entirely. On December 8, 1941, their invasion of Malaya began in concert with the attack on Pearl Harbor. They possessed airfields in Indochina that placed British shipping within comfortable reach of torpedo bombers and high level attack groups. Their air crews had practiced low level torpedo runs specifically designed to break open the hulls of capital ships. They deployed Mitsubishi G3M and G4M bombers in numbers sufficient to saturate any defense. Their commanders understood that speed and surprise favored them, and they moved accordingly.

When Force Z sailed from Singapore on December 8, the crew believed they could intercept Japanese landing forces and disrupt the invasion. At first, they moved northwest in search of the landing fleet. They kept the radios silent, which Phillips believed reduced the chance of detection. In reality, the force had already been spotted on December 9 by the submarine I 65, which tracked and reported their movement. Later that same day, three Japanese reconnaissance seaplanes confirmed the sighting. The Japanese 2nd Fleet prepared to intercept. Yet the real threat would not come from ships. It was circling above, waiting for the right bearing and altitude.

Later that evening, Phillips reversed course. He turned Force Z back toward Singapore once it became clear that surprise had been lost. More information arrived in the form of a reported Japanese landing at Kuantan, and Phillips diverted again. The maneuvering of Force Z during the night is sometimes described as a quiet dance along a coastline that had already fallen under enemy control. Fog of war stories often begin this way, with small unverified reports that alter decisions in ways that cannot be corrected later.

Just after 10 in the morning on December 10, a single Japanese aircraft flown by Second Lieutenant Hoashi Masane spotted the British force. Hoashi was not out looking for them. Chance favored him. He saw wakes on the water and identified the ships. His report triggered a convergence of bombers that had been awaiting such a sighting since the previous day. At this point Phillips still maintained radio silence, and no Allied aircraft were in the sky above his ships.

The first attack wave arrived at 11:13. High altitude bombers came in first. Repulse managed to evade several bombs through skillful handling by Captain William Tennant. One bomb struck her but did not cause serious damage. The sea at this moment resembled a chaotic geometry exercise, with a battlecruiser carving rapid S turns while white plumes rose where bombs fell into the water. Tennant seemed to have an instinctive understanding of his ship. Crewmen reportedly felt the deck shift beneath them with a sort of animal quickness.

Prince of Wales was not so fortunate. At 11:44 a torpedo struck her port side near the outer shaft. That single impact produced catastrophic flooding. Water rushed into the shaft alley and machinery spaces. Bulkheads that were designed to withstand damage gave way as the distorted shaft tore through seals and framing. Within minutes, the ship developed a heavy list. Power flickered out in multiple compartments. Anti aircraft guns that required electrical systems fell silent. Steering failed. A modern battleship that had taken on Bismarck months earlier was now limping, losing the battle not through gunnery but through engineering collapse. The crew fought to counter flood, but the sea had already chosen its path.

Japanese torpedo planes returned to exploit the weakness. Three more torpedoes struck the starboard side, sealing the ship’s fate. Prince of Wales slowed to a near standstill. Smoke rose from the deck as men carried wounded sailors to makeshift treatment stations. At 12:44 a high level bomber dropped a weapon that pierced deep into the interior and exploded within the casualty station known as the Cinema Flat. A survivor later described a sudden blast of heat and a sound like the sky breaking apart.

Repulse continued to maneuver, still managing to dodge several incoming torpedoes. Her crew cheered each near miss, as if effort alone might preserve the ship. The cheers ended at 12:19 when several torpedoes struck in rapid sequence along her side. She rolled quickly, losing stability. Captain Tennant ordered abandon ship. Repulse sank at 12:32. The sea closed over a battlecruiser that had once steamed proudly with Admiral Beatty’s force. Her final minutes demonstrated the limits of courage against mathematics. Torpedo defense systems built in the First World War could not withstand concentrated modern attacks. The lessons fell into place one after another, and none were new. They were simply ignored until the moment ignoring them became impossible.

Prince of Wales lasted a short while longer. At around 13:10 the order to abandon ship was given. Reports say the ship heeled to port while men climbed down ropes or jumped into the water. Some described oil slicks that looked like dark clouds drifting on the sea surface. Others remembered explosions echoing as compartments gave way. At 13:18 the battleship rolled onto her side and slipped beneath the surface stern first. Admiral Phillips and Captain John Leach remained aboard. Both went down with the ship.

The Japanese lost only a handful of aircraft in the attack. Their success confirmed what they had trained for. Large ships moving without air support presented easy targets. Their torpedo pilots had refined techniques for attacking from multiple angles, overwhelming even the best maneuvering. The battle demonstrated a cost ratio that modern doctrine would later cite as proof that aircraft carriers, not battleships, controlled the seas.

The death toll from the loss of Force Z reached 840 men. The number is stark enough, but it sits in the mind more sharply when placed beside the accounts of the survivors. The destroyers Electra, Vampire, and Express turned rescue operations into something close to a choreographed act. Electra rescued more than five hundred men from Repulse. Vampire collected over two hundred. These destroyers maneuvered among oil slicks and debris, pulling exhausted sailors up by the arms. Nearly 2,350 survivors were lifted from the sea. Many would later describe the strange silence that fell as they watched the last bubbles rise from where the capital ships had gone down.

The strategic impact arrived instantly. Without heavy surface vessels in the region, Britain and the United States had no credible naval force in the Western Pacific. Japan possessed uncontested control of the sea approaches to Malaya and Singapore. The fall of the two British capital ships meant that the advance down the Malay Peninsula could proceed without meaningful interference. Morale among Allied troops dipped sharply. On February 15, 1942, Singapore surrendered in what Winston Churchill called the greatest disaster in British military history. The fall of Singapore cannot be attributed solely to the loss of Force Z, but the ships had represented the last major symbol of British power in the region. When they disappeared, so did any illusion of control.

Historians sometimes use the phrase doctrinal epitaph when describing this event. Battleships had dominated naval thought for decades. Their armor and guns represented strength in a way no aircraft could match visually. Yet the air delivered weapons of greater reach and precision. After December 10, 1941, no Allied capital ship would again sail into contested waters without air cover. The sinking of the Japanese battleship Yamato in 1945 confirmed what Force Z had already demonstrated. Battleships could no longer operate independently. They were targets waiting for the right angle of approach.

Time has not been gentle to the wrecks of Prince of Wales and Repulse. They rest in Malaysian waters as official war graves. The sea has grown quiet above them, but human scavengers have not. Illegal salvage crews have cut into the hulls with explosives and cranes. Low background steel, prized for scientific instruments, has been removed from the wrecks. Copper and other metals have been stripped away. A Chinese salvage barge spent nearly three months operating illegally at these sites, leaving behind long trails of oil and a wake of environmental harm. Even worse, human remains have been disturbed. The desecration of these graves reveals a gap in maritime law that nations have not yet bridged.

Britain has attempted to monitor the region using satellite technology and AI based tracking. Malaysia has detained some salvage vessels and raided scrap yards. But the problem persists. It reveals something that many prefer not to admit. Memory and reverence are strong emotions, yet they do not prevent determined people from cutting into the past if they believe it will yield profit. In this sense, Force Z continues to remind us of vulnerability. Not the vulnerability of steel to torpedoes, but the vulnerability of memory to indifference.

The loss of Force Z was not a simple mistake or a single bad decision. It was a culmination of assumptions that had guided policy for a generation. When sailors later recalled the day, they did not describe doctrine. They described sunlight glinting on water, the vibration of engines struggling to respond, the shockwave of torpedoes, and the feeling that the world had changed faster than anyone could comprehend. They described the human face of a moment when an old order finally yielded to a new one.

Today, when people visit Singapore or read about the Pacific War, they encounter the story in fragments. Some focus on the bravery of the crews. Others examine the strategic failure. Veterans who listened to the news in 1941 often recall the sinking of Prince of Wales and Repulse with a particular sadness. It confirmed something that many feared. The empire could no longer protect its vast holdings. The technology that shaped the First World War no longer held authority over the next.

There is a temptation to force a moral into stories like this. That temptation should be resisted. The loss of Force Z does not offer neat lessons. It offers reminders instead. Reminders that doctrine can lag behind reality. Reminders that institutions are slow to change. Reminders that courage cannot compensate for the simple physics of war. The ships were mighty. Their crews were skilled. Their admirals believed in them. None of that mattered once a single pilot looked down from a bomber and recognized the unmistakable profile of two capital ships outlined against the sea.

One might say the story ends there, with metal sinking and history moving on. But the sea does not forget easily. Oil still rises occasionally from the wreck sites. Fishermen sometimes report seeing shapes beneath the water that resemble hull sections. Relatives of the lost still leave flowers at memorials in Britain. These gestures remind us that history is not only a ledger of decisions. It is a record of lives, hopes, failures, and courage carried into situations no one fully understood at the time.

Force Z sailed believing in the old world. It died in the new one. That moment of transition holds a kind of melancholy beauty. A bit like the worst poetry in the universe, the words of the past were still echoing even as reality rewrote the verse. The Hitchhiker’s Guide might have inserted a wry comment here about the futility of ignoring air cover while traveling through hostile territory, but the sailors aboard Prince of Wales and Repulse did not live in a satirical novel. They lived in a world that changed faster than they could adapt.

As a historian wandering through this hallway of memory, one does not try to tidy the score. It is enough to point at a few of the fingerprints still visible on the banister and listen for the distant echo of a diesel engine fighting a list. The loss of Force Z is many things at once, and none of them fit neatly into a box. It is a naval tragedy. It is a pivot in strategic thought. It is an epitaph to a doctrine that had ruled the seas for forty years. It is also a story of courage and failure intertwined, as so many wartime stories are.

The sea that swallowed these ships is still out there, quiet and indifferent. The lesson it offered on that December morning was costly, and the world learned it quickly. Battleships would never again claim mastery of the oceans on their own. That claim now belonged to the sky.

And so the story lives on. A reminder, a warning, and a quiet elegy for the last breath of an era.

Leave a comment