The story begins in a world that was still rubbing its eyes after the shock of 1945, a world that had seen one kind of bomb in Hiroshima and Nagasaki and now discovered that the scientists who built it had only just begun to imagine what the atom could do. Eisenhower stepped into the presidency in 1953 with the calm demeanor of a man who had carried the weight of millions of lives on his shoulders during the war. That calm was not serenity. It was a thin shield grown out of habit, the way seasoned officers carry themselves when they know the danger is real and the room is full of people who believe otherwise. The United States had detonated a hydrogen device in the Pacific in late 1952 that exceeded any previous notion of destructive power. The Soviet Union followed suit only months later. The planet suddenly felt smaller. The oceans felt narrower. The horizon felt closer. The ancient idea that America could stand behind its two wide moats and choose its conflicts began to dissolve like morning mist. For the first time since the republic’s birth, another nation held a weapon that could reach across oceans and strike at its heart.

Eisenhower understood that vulnerability quickly. He had commanded armies that measured destruction in divisions and corps and miles of front line. Now he was handed a scale of destruction so large that the military vocabulary of the past sounded like a child’s arithmetic. In one of the more sobering lines in his December address to the United Nations, he noted that the American stockpile already exceeded the explosive power used by every combatant in the entire Second World War. He said it calmly, the way people recite plain facts, yet that line carried the chill of a man who had looked across too many battlefields and who knew the price already paid by millions. He was not a man given to melodrama. He was a man who had watched history swing on the hinge of human folly, so when he said the numbers were awful he meant it literally.

This new arithmetic created a strategic puzzle with no satisfying solution. The United States had pursued a policy often summarized, sometimes too casually, as Massive Retaliation. The idea was that overwhelming force would deter any first strike. It sounded simple and strong. It also carried a hidden trap. If both sides possessed weapons that could wipe out cities in an afternoon, any miscalculation could become a catastrophe. Superior numbers no longer offered real security. Eisenhower knew that as clearly as he knew his own name. He had lived long enough to distrust the seductive logic of bigger arsenals and more powerful bombs. They solved a problem while creating another, then lulled nations into believing that the danger was under control.

That was the bleak canvas behind the speech he brought to the United Nations on December 8, 1953. The public saw only the podium and the flags and the carefully prepared text. Behind the scenes there had been months of work under the curious title Operation Candor. The name sounded cheerful, almost like a wholesome public service campaign from a country that liked tidy lawns and polite neighbors. In reality it was an attempt to speak honestly about the nuclear age without frightening the world into paralysis. The planners wanted people to understand the danger without succumbing to despair. They hoped to soften Soviet propaganda without setting off panic in Western capitals. They wanted to manage emotions, not conceal facts, and they understood that secrecy had created as many rumors as it had solved problems. A State Department report had urged the administration to speak openly about nuclear realities, and Eisenhower agreed. He had learned during the war that silence can breed disasters of its own.

Yet there was another layer to the plan. Operation Candor was also a strategic maneuver meant to shape the conversation about atomic power before the Soviets did. In that sense it resembled the kind of chess game where one tries to force the opponent into a line of play that appears harmless but soon becomes decisive. Eisenhower did not relish the need to use what he called the language of atomic warfare. He said he would have preferred never to speak that language at all. Nevertheless he stepped into that chamber with the steady posture of a general who had long ago accepted that history is not made by those who wait for ideal circumstances.

The heart of the speech was a proposal that sounded simple even though it was anything but. He told the world that the nations holding nuclear technology should contribute portions of their stockpiles to a new international agency created under the United Nations. That agency would store and safeguard the material. It would also supply nuclear fuel and expertise for peaceful uses. It would be a bank of fissionable material, guarded not by one nation but by many, locked away in such a manner that surprise seizure would be nearly impossible. The idea had two purposes. One was practical and technical. The other was diplomatic and moral. On the technical side, an international repository would make diversion or theft far more difficult. On the diplomatic side, the gesture itself would signal that the United States was willing to sacrifice some of its strategic advantage for the good of human progress.

Eisenhower described the peaceful uses of the atom in terms that blended practicality with a kind of restrained hope. He mentioned agriculture, medicine, and the promise of plentiful electrical energy for regions that had never known sustained prosperity. He spoke of the possibility that the atom, once harnessed for destruction, might now be redirected to improve the daily lives of people who would never attend a UN meeting or read a diplomatic transcript. This was the part of the speech that lent itself to lyrical interpretation. It recalled the ancient human longing that scientific knowledge might lift burdens rather than create new ones. It also carried the faint echo of a question that has haunted every age of invention. Would mankind finally use its ingenuity to save itself, or would it repeat the old pattern of turning every tool into a weapon. When Eisenhower promised to devote atomic energy to life rather than death, the statement had the quiet weight of a prayer spoken by a man who knew how fragile such promises could be.

He did not claim that his proposal would solve every problem. Instead he argued that it could be implemented without the endless suspicion that had doomed earlier attempts at international control. The Baruch Plan of 1946 had faltered because nations could not agree on inspection regimes. Eisenhower therefore suggested something less comprehensive but more feasible. Small contributions could begin immediately. The work of scientists could expand gradually. The symbolic value of cooperation could build trust over time. He listed several outcomes he hoped to see. One was the reduction of destructive stockpiles. Another was the global pursuit of peaceful uses. A third was the reassurance that the great powers placed human aspirations above geopolitical competition. A fourth was the opening of new paths for diplomacy. He did not present these outcomes as a neat set. They came across as overlapping aims, the way most real goals do when statesmen try to balance hope with reality.

The Soviets responded in the way seasoned observers expected. They offered polite interest, then criticized the plan for doing something other than what they insisted ought to be done. They argued that the first task should be the unconditional prohibition of atomic and hydrogen weapons. They suggested confidential negotiations rather than public commitments. They claimed that without a guaranteed halt to weapon production the proposal was incomplete. In other words they fought the battle over who would define peace. This was familiar ground in Cold War diplomacy. The Soviet Union framed peace as the elimination of weapons. The United States framed peace as the creation of mechanisms that would guide nations toward responsible stewardship. To many observers it looked like two musicians who refused to accept the same tuning fork.

Other nations listened with a mixture of eagerness and suspicion. Many in Asia, Africa, and Latin America were newly independent or in the middle of political transformations. They saw nuclear technology as a possible route to modernization. They also recognized that the United States hoped to shape global nuclear markets and maintain prestige. Some welcomed American help. Others resented the implied hierarchy. Delegates at the Bandung Conference in 1955 praised the promise of peaceful nuclear applications while simultaneously demanding a halt to weapons tests. They talked about nuclear power as a symbol of national pride and a doorway to development. At the same time they condemned the growing nuclear tensions that threatened to turn their homelands into future battlegrounds.

American officials tried to encourage regional cooperation by proposing a large research center for Asia, something that would resemble the European Euratom model. They offered significant funding, and they imagined a kind of shared laboratory where local scientists would work together. The plan failed for a simple reason. The participating nations were more interested in developing their own national programs than in joining a regional collective supervised by Americans. They had fought long and hard to become independent. They were not eager to place their scientific futures back under external influence.

A similar story unfolded in Latin America. Brazil, determined to achieve real energy independence, used the moment to demand more expansive assistance than the original Atoms for Peace framework offered. When American officials hesitated, Brazil pushed back. It suspended thorium and uranium exports to the United States in 1956. A potential American-built power plant later collapsed under financial strain, leading to a prestige setback. It was one thing to give a speech that made the world applaud. It was another thing to satisfy the hopes and demands that followed.

Inside the American government a few officials voiced quiet warnings. They noted that peaceful nuclear cooperation, however well intentioned, could spread knowledge that might one day be used for weapons. They observed that wherever nuclear power reactors traveled, the technique of plutonium separation traveled with them. These warnings surfaced as early as 1955, only two years after the famous speech. At the time they sounded like the kind of gloomy predictions that bureaucrats sometimes mutter during coffee breaks. History later elevated them to the status of foresight.

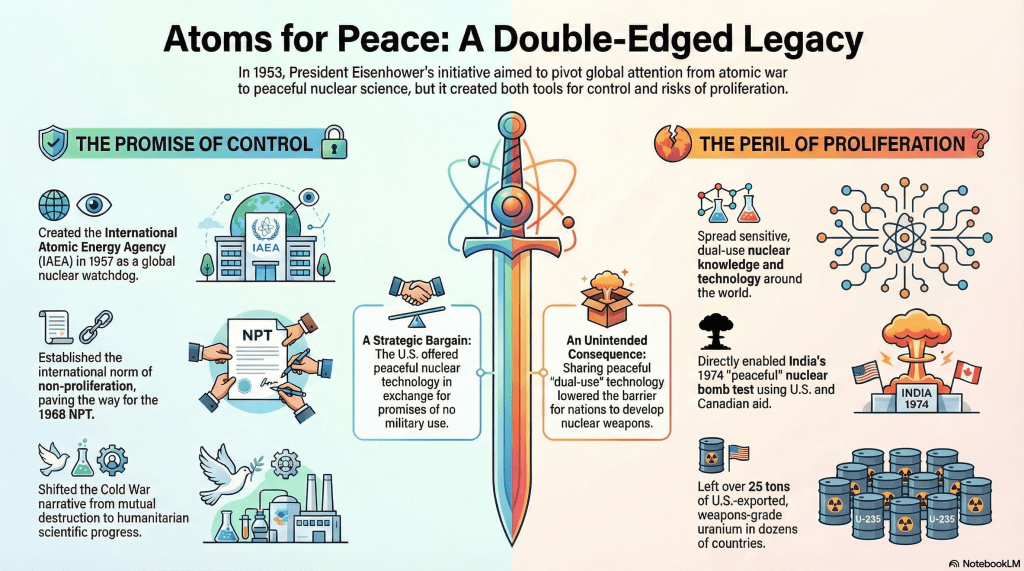

Despite these complications the proposal did bear institutional fruit. After years of negotiation the world created the International Atomic Energy Agency in 1957. That agency stands today as one of the most enduring structures of global governance. It monitors peaceful uses, distributes expertise, and operates a safeguards system that tries to ensure that nuclear material is not misused. It is the cautious referee in a sport that rewards skill but punishes foul play with consequences too great to imagine. Its creation took patient diplomacy at a moment when the Cold War was beginning to harden into familiar patterns of rivalry.

For the United States the initial enthusiasm for exporting nuclear know how eventually cooled. By the end of the 1950s the Atomic Energy Commission folded international reactor support into more general foreign aid programs. The early years of exuberant sharing were replaced by more cautious arrangements. The government recognized that the atom carried a dual personality. It could light cities or destroy them. It could power hospitals or produce plutonium. Every grant of technology contained a seed of risk.

That risk became painfully clear in 1974 when India conducted its first nuclear test. The device used plutonium produced in a reactor provided for peaceful research, with heavy water supplied by the United States and Canada. The explosion was called Smiling Buddha, though the name did not bring much comfort to the diplomats who realized what had happened. The test demonstrated that a determined nation could use the peaceful path to reach a military goal. It also triggered the creation of the Nuclear Suppliers Group and eventually led to the American Nuclear Non-Proliferation Act of 1978. Nations rewrote agreements. Export rules tightened. Verification systems expanded. The test had proved that the road to proliferation could run straight through the peaceful garden that Eisenhower had tried to cultivate.

Iran began its nuclear program through Atoms for Peace in 1957. It received technology, training, and American support. Over the decades that followed, the Iranian program became one of the central diplomatic concerns of the modern world. Yet the same system that enabled peaceful beginnings also helped detect and deter efforts by other countries to pursue weapons. Argentina and Brazil stepped back from military paths. South Korea and Taiwan abandoned early pursuits under pressure and persuasion. The mixed legacy of Atoms for Peace therefore revealed itself in real time. It empowered some states to advance toward capability. It also built the institutions that helped limit the spread.

There is a certain irony here, the kind that Douglas Adams would have appreciated. Mankind sought to build a world where the atom would serve the plow and the hospital bed, yet in doing so it created a global network of inspectors who now spend their careers making sure the atom does not stray back into the shadows. It is the kind of cosmic humor that appears in both science fiction and history, the kind that reminds us that intentions are only the beginning of a story, never the end.

The speech also helped lay the philosophical foundation for the Treaty on the Non Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons, signed in 1968. The treaty built on the idea of a grand bargain. Nations without nuclear weapons agreed not to pursue them. Nations with nuclear weapons agreed to work toward disarmament and to provide peaceful applications of nuclear energy to those who renounced weapons. The International Atomic Energy Agency became the mechanism that verified compliance. In this sense Eisenhower’s proposal became the seed of an entire system that governs nuclear behavior to this day. It did not prevent every danger. It did, however, prevent the world from sliding into the nightmare scenario predicted in the early 1960s, when some analysts believed that twenty or thirty countries would soon possess their own bombs.

Judging the legacy of Atoms for Peace is like examining an artifact with two faces. One side shows a diplomatic success. Eisenhower seized the moral initiative at a time when the world desperately needed reassurance that the great powers were not sleepwalking into disaster. He redirected the global conversation. He made nuclear energy sound like a tool of hope rather than a harbinger of annihilation. He gave scientists a vision of peaceful cooperation. He offered newly independent nations a chance to join the modern world with dignity.

The other side shows a technical shortfall. The early years of generous sharing helped spread the knowledge that later enabled proliferation. The effort to reduce danger inadvertently created new dangers. Technology does not care about intention. It cares only about possibility. Once knowledge spreads it does what knowledge has always done. It invites use, cleverness, ambition, desperation, and occasionally mischief.

Eisenhower probably suspected this paradox. He was too experienced to believe that any policy would produce only the results one hoped for. He understood that the world was moving into an age when no nation could insulate itself from its own inventions. He believed that creating an international framework was the best available option. The framework might not achieve perfection, yet without it the world would certainly face chaos.

The verdict of history is therefore mixed and honest. Atoms for Peace did not halt proliferation, but it did create the institutions and norms that give the modern world tools to restrain it. It did not prevent the first diversions of peaceful technology toward weapons, yet it eventually built the rules that reduce the likelihood of future diversions. It did not eliminate fear, but it offered a story that could counter despair.

Most of all it revealed something about the era and the man who delivered the speech. Eisenhower had commanded the largest amphibious invasion in human history. He had watched ordinary men accomplish impossible feats. He had seen cities ruined by bombs and then rebuilt by hands that refused to surrender. When he stood before the United Nations he carried the memory of a world that had lost too much already. His appeal for peaceful uses of the atom was not sentimental. It was not idealistic. It was practical, born from a military mind that had learned the hard lesson that even victory leaves scars.

The speech matters today because the nuclear world he helped shape is still the one we inhabit. The IAEA still investigates suspicious facilities. Nations still argue about enrichment levels. Treaties still balance rights with responsibilities. Terrorists still search for fissile material. Scientists still build reactors that promise cleaner energy. Politicians still make speeches about responsibility. The entire complex system of modern nuclear governance, with all its strengths and flaws, still traces its ancestry back to that moment in 1953 when a five star general turned president decided that honesty might be the only weapon powerful enough to counter fear.

It is tempting to treat the speech as a relic from a simpler age, but that would be unfair to the reality of the time. The people of 1953 did not feel as though the world were simple. They felt the weight of dread every time a headline mentioned nuclear tests. They listened for sirens and checked the skies. They read articles filled with diagrams that looked like they had been drawn by students who had spent too much time reading the worst poetry in the universe. They knew they were living in a strange new age, one in which a single weapon could flatten a city while promising electricity too cheap to meter. It sounded like something from a Hitchhikers Guide footnote, the kind that explains how a technology can be both brilliant and catastrophic depending on who uses it.

The true legacy of Atoms for Peace is not a tidy moral lesson. It is the continuing recognition that nuclear technology will always carry hope and hazard side by side. Eisenhower tried to steer humanity toward hope. He did not fully succeed. No one could. Yet he created the stage on which future generations would struggle with the same questions. His speech reminds us that leadership sometimes means admitting that a problem cannot be solved completely. It means choosing the path that reduces risk rather than eliminating it. It means trusting institutions even when they seem slow and imperfect. It means accepting that human beings, for all their cleverness, must live with the consequences of their own inventions.

The speech endures because it tells the truth about a species that dreams of lighting the world while discovering that its brightest flames cast the darkest shadows. It endures because Eisenhower spoke as a man who had known both the cost of war and the stubborn resilience of people who rebuild after it. He believed that mankind could find a way to live with the atom rather than perish by it. He believed that even imperfect frameworks were better than unrestrained rivalry. He believed that knowledge, once born, could be guided even if it could not be undone.

Walking back through the speech today feels like wandering an old hallway where the plaster has cracked and the banister bears the fingerprints of generations. You can see where the paint has faded. You can also see where the structure still holds. That hallway leads from the fear of 1953 to the uneasy stability of the present. The world has fewer nuclear states than many once feared. It also has more nuclear knowledge than Eisenhower could have imagined. It is still balancing hope and hazard. It is still arguing about trust. It is still searching for ways to make the atom serve life rather than death.

Eisenhower did not offer a perfect solution. He offered something different. He offered a beginning. For a planet that had already glimpsed the edge of absolute destruction, a beginning was not a small thing. It was a turning of the wheel, a shift in the narrative, a reminder that even in the presence of terrible power, human choice still matters. That reminder, spoken with calm and gravity by a general who knew the consequences of war far too well, remains the enduring gift of Atoms for Peace.

Leave a comment