There are stories from the Second World War that seem to have been written by a nervous committee of novelists who could not quite decide whether to craft an adventure, a tragedy, or a comedy of bureaucratic errors. Operation Frankton tends to sit in that uneasy place, a tale of quiet courage and outrageous improvisation that begins with a group of Royal Marines paddling collapsible canoes into the heart of German controlled France and ends with the bitter realization that heroism does not always compensate for human folly in high places. It is also a story that generations of schoolboys once whispered with a kind of reverence, mostly because no one could believe that grown men had willingly set off to fight the Third Reich armed with nothing more than paddles, limpet mines, and a determination that bordered on the poetic. The nickname did not hurt either. The Cockleshell Heroes. A name that sounded whimsical enough to disarm the truth, which was far harsher and more impressive than any screenplay Hollywood ever attempted to bolt together.

The raid took place in December of 1942, at a moment when the tide of war had not yet turned and when Britain found itself hurling pebbles at what appeared to be a granite wall. German shipping was sailing into and out of the port of Bordeaux with the smug confidence of a school bully who had just discovered that the teacher was on permanent leave. Rubber, oils, and a catalog of raw materials essential to the German war engine drifted into France unmolested because conventional attacks were too costly and diplomatic consequences too risky. The Merchant Navy had been mauled across the Atlantic. The Luftwaffe maintained a stranglehold. Britain, with its energy stretched thin across every continent, settled for daring little raids that could, at the very least, signal to Berlin that the British spirit had not yet been logged and stacked like firewood.

Into this world stepped Major Herbert Blondie Hasler, a Royal Marine officer with the peculiar blend of imagination, persistence, and restlessness that often serves as the fuel for unorthodox operations. Hasler was a peacetime sailor, which meant he understood the moods of winds and tides far better than most of the officers debating strategy in Whitehall. He believed that a canoe could slip into a port more effectively than any warship. He also believed, against all common sense, that two men in a collapsible boat could creep beneath Germany’s nose and send its ships to the bottom with a few well placed mines. The idea was so improbable that Combined Operations rejected it outright when he first proposed it. Fortunately for Hasler, the Italians had recently struck British ships using small human guided torpedoes, which proved that small teams with unusual tools could do significant damage. Suddenly Hasler’s canoe vision did not seem quite as mad.

The Royal Marines Boom Patrol Detachment was born from that shift, a unit so small that the average parade ground sergeant would have dismissed it as insufficient even for a cricket team. They trained in Scotland and the Thames, paddling under rain, wind, and the weary glances of passing fishermen who likely wondered whether a war had truly broken out or whether these marines had lost a bet. Their craft, the Mark II Cockle, resembled something a thoughtful Boy Scout might have assembled from spare canvas and stubbornness. It folded in half, fit through a submarine hatch, and carried two men, eight limpet mines, and enough rations to survive the long paddle up the Gironde estuary. The canoe was as fragile as a promise and as vital as a heartbeat.

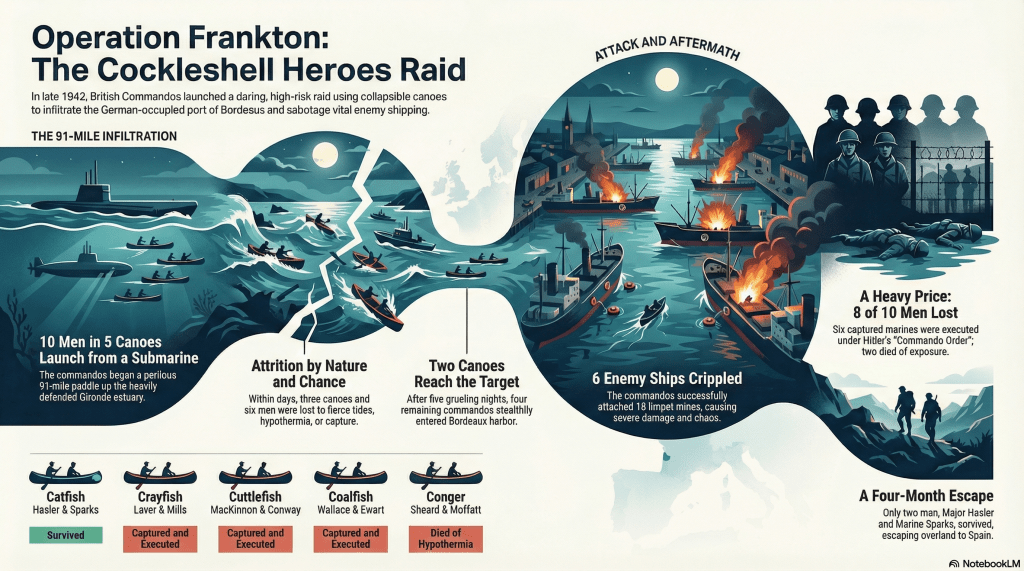

By late November 1942 the men and their canoes were aboard HMS Tuna, a T class submarine whose crew must have wondered what precisely was in store for them. Submarines tend to carry torpedoes, not kayaks. Yet the plans were firm. On December 7 the canoes would be passed out through the hatch, unfolded, loaded, and set loose to begin a seventy mile paddle toward Bordeaux. From there the marines would slip among the anchored ships, plant limpet mines, and escape overland into Spain, a journey of several hundred miles that was an adventure all its own. It was bold in the way that only war can encourage, the kind of boldness that later makes historians murmur that someone should have known better.

The mission faltered almost instantly. One canoe, Cachalot, was damaged during the transfer from the submarine. It never entered the water. That reduced the raiding force from six canoes to five before the first paddle stroke. When the remaining ten men set off they immediately discovered that the tides of the Gironde were not polite co participants in the affair. They were wild, unpredictable, and entirely uninterested in the finer points of clandestine operations. Sergeant Wallace and Marine Ewart, in the canoe codenamed Coalfish, vanished in the chaos of the churning water. They were swept ashore and captured by German forces. Three days later they were executed under Hitler’s Commando Order, a decree that had the decency to pretend the Geneva Conventions had never existed.

Not long after that, the canoe Conger capsized. Corporal Sheard and Marine Moffatt attempted to swim for land in the freezing water. They did not make it. Hypothermia does not negotiate and it does not offer second chances. The mission, scarcely one night old, had already lost four men. A third canoe became separated. Lieutenant Mackinnon and Marine Conway spent hours dodging German patrols before their craft struck an underwater obstacle and sank. They tried to escape overland, only to be captured and later executed in the same grim machinery of the Commando Order. Of the original twelve marines and six canoes, only four men and two boats remained.

This would have been the point in most military operations when the commander quietly declared the mission compromised and ordered an extraction. Hasler did not have that option. There was no extraction. There was no plan B. If he and his remaining partner, Marine Bill Sparks, turned back, they would have to make the return paddle under the same unforgiving tides. If they pushed forward, they had a faint chance of reaching Bordeaux. If they stayed put, they would die. Those are stark calculations that leave little room for rhetoric. Hasler and Sparks pressed on. With them went Corporal Albert Laver and Marine William Mills, paddling in the remaining canoe. The two teams began the long crawl toward the port, slipping past German gunboats and the sweeping beams of searchlights that clawed across the water like impatient fingers.

The progress was uneven. Twenty miles on the first night. Twenty two on the second. Fifteen on the third. Nine on the fourth, which brought the entire plan into jeopardy. The tides were running too strong, the water fighting them like a living thing. Hasler postponed the attack night to preserve the one advantage they still possessed, the ability to appear in Bordeaux when the Germans least expected a sneak attack by canoe. They had traveled roughly ninety one miles before they reached the harbour, and by then they were exhausted, light starved, and existing mostly on the dull determination that keeps people moving long after the phrase give up has crossed their mind.

On the night of December 11 the attack began. Hasler and Sparks took the western side of the harbour and planted their mines on four vessels, including a patrol boat. A German sentry caught them in his torchlight for a few heartbeats that must have felt like a lifetime. He saw nothing. They slipped away, paddles whispering against the dark water. Laver and Mills found the quays on their side empty, so they continued on to Bassens where they placed mines on two additional ships. All four men then retreated, scuttled their canoes, and began the long foot journey toward the Pyrenees.

The mines detonated early in the morning. Ships buckled, burned, or sank. The blockade runner Tannenfels listed heavily before being used as a blockship. The freighter Dresden suffered severe damage and later sank after its propeller shaft was destroyed. Other vessels, including Alabama and Portland, required months of repairs. German commanders were bewildered and enraged. They had not imagined that Britain would send commandos into their fortified harbours, much less commandos who arrived in collapsible canoes. Mountbatten later declared the raid the most courageous and imaginative of the war. Churchill believed it shortened the conflict by six months. Hitler, for his part, was furious. Admirals who lose ships tend to have difficult conversations with dictators.

The triumph ended quickly for Laver and Mills. French gendarmes captured them within two days of the attack. They were handed over to the Germans who executed them in March 1943. Mackinnon and Conway, captured weeks earlier, were executed at the same time. The story of their final days remains one of the darker notes in a mission that already had enough gloom to fill a minor epic. The Commando Order was a reminder that the war, for all its grand speeches and righteous slogans, was still a struggle in which men could be murdered simply for being brave in the wrong place at the wrong time.

Hasler and Sparks became the only survivors. They escaped with the aid of the French Resistance, hiding for six weeks before climbing across the Pyrenees into Spain. Their success carried the peculiar mixture of triumph and grief common to the survivors of such missions. They had accomplished what they set out to do. They had proven the worth of their little boats. They had disrupted German supply lines. Yet every other man who had launched from HMS Tuna was now dead. Hasler later said that success felt hollow, a sentiment anyone who has endured loss can understand. Awards followed in the form of the Distinguished Service Order for Hasler and the Distinguished Service Medal for Sparks. Posthumous mentions in dispatches recognized the others. Medals have their place, but they do not answer the questions that linger in the quiet hours, nor do they explain the failures of institutions that sometimes let their bravest men down.

What made Operation Frankton especially tragic was not the sacrifice itself, which the men had accepted, but the revelation that another British operation had been planned for the same target at the same time. The Special Operations Executive, which guarded its secrets with a zeal that would embarrass a dragon, was preparing sabotage teams under the leadership of Claude de Baissac. They planned to strike the same ships that Hasler and his men targeted. Yet because Combined Operations and SOE refused to share their plans, neither organization knew of the other. De Baissac was preparing his explosives when the Cockleshell mines detonated. A coordinated strike could have inflicted even greater damage. Instead, the right hand and the left hand behaved like rivals in a poorly written comedy, each refusing to acknowledge the existence of the other. The aftermath forced Whitehall to create a coordinating officer to oversee such missions. It was a lesson carved from the lives of men who did not live long enough to see bureaucrats admit their mistakes.

Over time the raid took on a mythic quality. The number of damaged ships grew in the telling. The courage of the marines became a symbol of defiance. The Royal Marines Boom Patrol Detachment eventually evolved into the Special Boat Service, a lineage that modern SBS operators acknowledge with a mixture of pride and humility. Films attempted to tell the story. The Cockleshell Heroes, released in 1955, dressed the events in cinematic clothing that made Hasler bristle. He disliked the title, believing that it trivialized his men, and he walked away from the production. Perhaps he feared that audiences would remember the nickname and forget the real people who had endured cold, exhaustion, and death. Historians later attempted to correct the record. Paddy Ashdown, himself a former SBS officer, wrote A Brilliant Little Operation, an account that navigates the raid with precision and reflects on its human cost. His documentary for the BBC brought the story to a new generation, though even he admitted that no retelling could quite capture the intimate terror of paddling in pitch darkness toward a fortified enemy harbour.

There is a temptation to treat Operation Frankton as a historical curiosity, a footnote in the long record of the war. That temptation should be resisted. The raid demonstrated that ingenuity can sometimes subvert overwhelming power. It showed that ordinary men, given a strange assignment and flimsy equipment, could alter the shape of a conflict if they were willing to risk everything. It also revealed the failures beneath the surface, the rivalries and silences that cost lives as surely as enemy bullets. These contradictions are part of its strength. Stories that survive tend to be the ones that refuse to settle into a single meaning.

Hasler once wrote that war is a series of uncomfortable compromises between what must be done and what can be done. The Cockleshell Heroes lived that truth. They paddled into a maze of tides and patrols knowing full well that rescue was unlikely. They pressed forward in the belief that a handful of men could damage the German war machine enough to matter. Their courage did not erase their fear. Their resolve did not diminish their weariness. They were not superheroes. They were men who decided to act, knowing they would probably not return.

It is easy to admire such courage from a safe distance. It is something else to imagine the raw, cold water of the Gironde licking at a canvas hull or the sudden flare of a German searchlight sweeping across the river. The mission was not glamorous. It was grueling and lonely and marked by moments of doubt that could crush a weaker spirit. Yet something in the human heart responds to tales of difficult journeys undertaken for reasons larger than the self. It is why the story endures. It is why people still walk the Frankton Trail in France, tracing the escape route of Hasler and Sparks. It is why the names of the dead are carved into memorials at Plymouth and Portsmouth.

Operation Frankton remains a story without neat lines or final answers. It contains courage and tragedy, ingenuity and institutional failure, triumph and loss. It is the kind of story that history tends to generate when the stakes are highest and the world is at its most unpredictable. It deserves to be remembered for all that it was, not just the parts that fit easily into patriotic posters or cinematic recreations. The Cockleshell Heroes were real men, not symbols. Their ordeal was real. Their bravery was real. Their fate was shaped by forces both human and political. Their legacy lives on in the quiet acknowledgment that the most improbable missions can sometimes succeed, and that sometimes success demands a price paid by those who never get to see it.

In the end, the raid stands as a testament to what can happen when ingenuity meets determination, and as a warning of what happens when institutions fail to speak to one another. It is a reminder that the past is not composed of tidy lessons. It is a collection of human moments, each shaped by decisions made in cramped submarine compartments, on cold riverbanks, and in the shadowed offices of Whitehall. The Cockleshell Heroes moved through those moments with a steadiness that deserves respect. Their story, strange and compelling, still whispers through the long corridors of history like the sound of a paddle dipping into dark water.

Leave a comment