George Armstrong Custer entered the American story on December 5, 1839, in the quiet crosswinds of New Rumley, Ohio, a place that offered very little hint of the larger storms he would run toward for the rest of his life. His name would one day be welded to both glory and catastrophe, and it remains suspended between the two like a coin that someone kept flipping long after the game ended. Custer has that paradoxical quality that certain nineteenth century figures hold, a flair for stepping directly into the nation’s own growing pains and then becoming a symbol for them. The man died young, yet somehow he occupies more historical real estate than many who lived twice as long. He did not ask for that. Or maybe he did, just not in so many words. Men of his ambition usually send up a signal or two. Still, even he could not have imagined that his final moments on a Montana hillside would bloom into a mythology that would outlive every one of his critics and defenders.

He was raised partly in Monroe, Michigan, in the home of his half sister, where family influence and a certain restless energy shaped him long before he put on a uniform. Young George displayed the kind of buoyant confidence that teachers often mutter about in the hallways. When he entered the United States Military Academy in 1857, personal discipline and academic rigor did not immediately capture his interest. He graduated dead last in the class of 1861, a fact that has been repeated so often it has become the historical equivalent of a knock knock joke. Yet even here the story resists simple interpretation. Cadets often said Custer had more charm than caution, more sparkle than order, and he seemed to understand early that people remember the flourish long after they forget the regulation. One classmate recalled him as “a fellow of dash and deviltry,” and while that sounds like the sort of line a novelist would punch up, it stands as a clue to the man he already was.

Then came the Civil War, and the country discovered that Custer was made for precisely the kind of chaos it dreaded. He rose with a speed that left some officers blinking in disbelief, gaining attention first for his daring reconnaissance work and then for leading charges that looked suicidal until he made them work. At Gettysburg in July 1863 he led a cavalry assault so violent the horses themselves seemed bewildered. He shouted “Come on, you Wolverines” as if the entire Army of the Potomac needed only a good cheer to make the Confederacy tremble. The Confederate officer Wade Hampton reportedly asked after the battle who the “young man with the yellow hair” was who kept riding straight at him. Custer wrote afterward that “the enemy seemed to hesitate under the boldness of the onset,” which is one way to describe an attack that came within a breath of turning the tide on that part of the field.

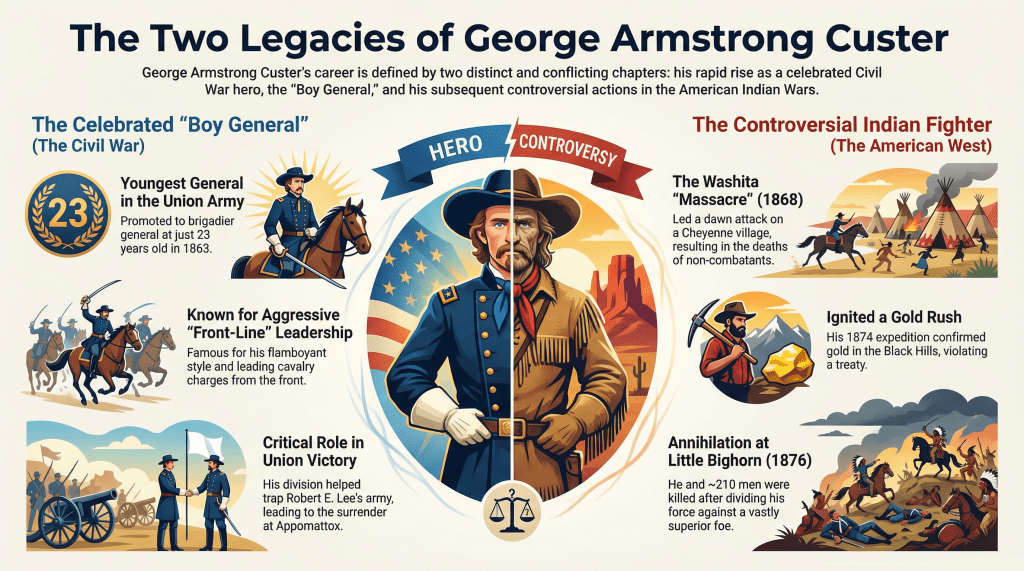

He received his brevet rank of brigadier general at twenty three, and newspapers began calling him the Boy General. The name stuck, and it flattered him, although he tried to hide the smile. His imprint on the Appomattox Campaign was carved clearly enough that General Sheridan singled him out, writing that Custer “was always where the danger was greatest.” When Robert E. Lee’s forces attempted their final breakout in April 1865, Custer helped block their escape. It was Custer who received the white flag from the Confederate envoy seeking the terms of surrender. Libbie Custer later wrote that her husband told her he felt a strange stillness at that moment, almost a disbelief that history would give a young man such a responsibility. It might have made him reflective for a time, though if so the feeling did not linger. Reflection was never his strongest field of study.

After the war he married Libbie Bacon, a woman of intelligence, presence, and admirable patience. Her father disapproved of the match until Custer’s rising reputation softened the old man’s objections. Libbie believed in him with a devotion that seems unusual even by nineteenth century standards. She understood that Custer’s confidence ran hot enough to scorch him, and she tried to steady him without quenching the flame. They built a marriage that looked from the outside like the partnership of a hero and his chronicler, though it was more complicated than that. Libbie provided the ballast. She also provided the narrative shape of his legend after his death, something that history would discover mattered nearly as much as anything he did while living.

In 1866 Custer accepted a lieutenant colonelcy in the new Seventh United States Cavalry and headed west. He discovered on those plains that the war he had fought against Confederates was entirely different from the war the government now intended to wage against Native nations. His Civil War habits followed him into a world that resisted neat transfer. He believed that boldness and speed unsettled an adversary. He believed that shock mattered more than arithmetic. He believed that victory rewarded initiative. These ideas served him well when the enemy wore gray. They carried a different cost on the Great Plains.

The winter campaign of 1868 brought him to the Washita River, where his attack on Black Kettle’s Cheyenne village remains one of the most debated episodes of his career. Custer called it a battle. Many later called it a massacre. Black Kettle could not have been more explicit about his desire for peace, yet he and his people were swept into the government’s larger strategy of breaking tribal strength through winter destruction. Custer wrote in his memoir that his men faced “a strong force of warriors,” but eyewitness accounts and later research make it plain that women and children died under the Seventh Cavalry’s fire. A Cheyenne survivor recalled that the soldiers “did not spare anyone,” a simple sentence that carries the weight of grief and memory. Custer believed the attack was a success because the village was destroyed and surviving hostages were taken. The calculation exposed a widening gulf between the way he measured victory and the way others would evaluate his actions later.

Custer’s star, however, did not dim in official circles. In 1874 he led a military expedition into the Black Hills. The region was legally guaranteed to the Lakota under the 1868 Fort Laramie Treaty, a fact that everyone involved either knew or pretended not to know. When Custer announced that his men found gold “among the roots of the grass,” the phrase sounded poetic enough to disguise the reality that the discovery would break the treaty as surely as if it had been set on fire in the middle of the parade ground. Newspapers in the East printed the gold reports with a cheerful enthusiasm that ignored the fact that they described an invasion. The flood of miners became a tide that no law would restrain. The government responded with policies that insisted the Lakota must return to reservations or be treated as hostile. Custer’s expedition was not the cause of the Great Sioux War of 1876, but it acted like a match held over dry tinder.

The campaign of 1876 sent several military columns into the northern plains. Custer rode with the Seventh Cavalry under the overall command of General Alfred Terry. There were decisions made during that march that continue to invite debate. Custer refused the offer of Gatling guns because he believed they would slow his column. He turned down additional infantry. He took the advice of scouts when it suited him and ignored it when it did not. Frederick Whittaker, who would become one of his earliest hagiographers, claimed that Custer “desired above all things to strike a heavy blow” before anyone else could reach the field. It is difficult to know whether Custer thought this blow would restore the political shine he felt slipping from him or whether he simply trusted the instincts that had served him so improbably during the Civil War. Either way, he rode toward the Little Bighorn River in late June believing he faced a manageable problem. Reality was already assembling something much larger.

The Native encampment near the Little Bighorn held thousands of Lakota, Northern Cheyenne, and Arapaho. It was one of the largest gatherings of these nations in living memory, forged partly by spiritual vision and partly by the growing urgency to resist reservation confinement. Sitting Bull’s vision, which he experienced during a Sun Dance, promised that soldiers would fall into the Lakota camp like “grasshoppers.” Crazy Horse, always difficult to pin down in any direct quotation, carried a resolve that others described as quiet and immovable. They were not expecting Custer personally. They were expecting a fight.

Custer divided his regiment into battalions, sending Major Reno to strike the upper end of the village and Captain Benteen off to scout a distant valley. Reno’s attack unraveled almost immediately under fierce resistance. He described the experience later, saying he felt the village “swarming with warriors.” When his line broke and he retreated to the bluffs, the situation turned into a desperate defense that would occupy him and Benteen for the next day. Benteen maintained a bluntness in his later testimony, remarking that Custer’s plan “was not one that would commend itself to any military man,” though he delivered the line with a casual dryness that leaves room for interpretation.

Custer rode north with roughly two hundred men and collided with a force so large that no amount of bravado could match it. Native accounts describe a fight that moved rapidly across the ridges, with warriors pressing in from multiple directions. One Northern Cheyenne participant recalled that “soldiers were shooting in every direction” and that many dropped their weapons once their horses fell. Archeological studies support the idea that the companies broke into fragments as they attempted to maneuver under overwhelming pressure. The last stand, as the story came to be known, unfolded on a hill now marked by white stones. It happened quickly. It happened without reinforcement. It happened because Custer misread a gathering of nations whose patience was already threadbare from broken promises. General Grant later remarked that Custer brought on “a wholly unnecessary sacrifice” of men. Sheridan, who had defended Custer more often than not, struggled to explain this defeat in any terms that suited either the Army or the public.

The news reached the East around the Fourth of July, a holiday that celebrates independence and optimism. One can imagine the shock when papers reported that Custer and his command had been annihilated. Writers scrambled to frame the story. Whittaker painted Custer as a Christian knight fighting until his last breath. Others blamed Reno or Benteen or the Army or Sheridan or anyone who seemed handier than the dead. The country needed a narrative that would fit the Centennial mood. Myth can be assembled quicker than a cavalry column when people desire it strongly enough.

Libbie Custer devoted the rest of her long life to preserving her husband’s reputation. She wrote three books that turned their frontier years into a kind of American Camelot. She presented him as noble, pure, brave, and unfailingly dutiful. She said he possessed a “kindness that never failed,” and she insisted that he stood as a model to young men everywhere. Her efforts created a silence that lasted for decades, because few wished to speak harshly of a widow who showed such loyalty. Reno and Benteen spent years defending themselves under the weight of the legend she built. Historians found that criticism of Custer during her lifetime was nearly impossible without appearing ungenerous. The record became a chorus with one dominant voice.

Custer entered popular culture with astonishing speed. John Mulvany created a painting of the last stand that toured the country like a relic. The Anheuser Busch lithograph appeared in saloons and parlors, shaping public imagination with a single dramatic image that showed Custer untouched by fear or doubt. The image bore only a passing resemblance to reality, yet it lived on because it offered something the real battle did not provide, a sense of heroic symmetry in a world that often refuses it. Later films swung wildly in tone. Some turned him into a triumphant martyr. Others recast him as a vain blunderer. One generation’s hero became another generation’s lesson. Then he became a curiosity, and eventually he became a mirror for the country’s own unresolved arguments about conquest, responsibility, and identity.

Modern scholarship looks at Custer with a mixture of bewilderment and fascination. Custerology, as some call it, is not really a study of Custer alone. It is a study of the ways a nation constructs meaning from triumph and disaster. It is a study of the West as imagined by people who often knew it only through paintings and dime novels. It is a study of Native persistence in the face of overwhelming federal pressure. When the government renamed Custer Battlefield National Monument to Little Bighorn Battlefield National Monument in 1993, the decision signaled a recognition that the story was larger than one man’s last moments. Native voices became central to the interpretation of the site. Their accounts describe a victory, hard fought and fully earned, a moment when people defending their homelands prevailed against a military expedition that underestimated them.

Custer’s life reads like a lesson in the hazards of brilliance without restraint. He possessed courage that was almost theatrical in its boldness. He also possessed a streak of confidence that made him believe the universe favored his survival. Soldiers called his improbable escapes “Custer luck,” a phrase whispered with respect during the war. By 1876 it had stretched so thin that the wind could tear it. Yet even here, at the edge of the story, irony intrudes. Custer died in a battle that should have been remembered primarily for Native skill and determination. Instead the country attached his name to it, elevating him into a symbol that overshadowed those whose victory it truly was.

He matters today not because he represents an easy moral or a tidy cautionary tale, but because the questions his story raises remain unsettled. How should a country remember its expansion when that expansion brought profound suffering to others. How does a soldier balance boldness with judgment. How does a nation decide which tragedies become myths and which become warnings. These are not simple questions. They never have been. Custer’s story does not answer them, but it refuses to disappear because it contains enough contradiction to keep modern readers uneasy. It asks us to face the distance between what we wish the past had been and what it actually was.

George Armstrong Custer lived in a world where youth, courage, and spectacle could carry a man astonishingly far. He died in a world shaped by treaties broken as soon as they became inconvenient. He occupies a place in American memory that few others share, a place where admiration and criticism stand so close together they almost shake hands. His life was short, brilliant, troubled, and unfinished in a way that allows generation after generation to return to it, each finding new interpretations in the same scattered bones and spent cartridges. His last stand endures not because it was glorious, but because it was human. It was shaped by ambition and miscalculation, by resolve and misunderstanding, by the grinding collision of cultures that neither trusted nor comprehended each other.

The man who once charged through Gettysburg fields with his yellow hair streaming behind him became a national riddle. Perhaps that is fitting. The past rarely resolves itself neatly. Instead it leaves us with stories like Custer’s, where the edges fray and the meanings shift when held up to the light. The historian walks through that hallway of memory and points out the fingerprints on the banister, the cracks in the plaster, and the places where the truth refuses to sit comfortably. Custer lived along those fault lines. That is why he endures.

Leave a comment