There are some lives that feel as if they were written by a cosmic prankster who enjoys a good twist more than any reader ever could. Eiji Sawamura’s story is one of those lives. A teenager with a right arm that made legends blink. A young man who helped invent professional baseball in Japan. A soldier drafted into three tours of war until his gifts were wrung out of him like a rag hung over a bucket. A national icon whose death came at the hands of a nation whose greatest ballplayers he had once humiliated. There are tales in history that feel too sharp to touch barehanded, and this is one of them.

His life is remembered in the Sawamura Award, a Japanese mirror to the Cy Young Award, handed out each year to the best pitcher in Nippon Professional Baseball. That trophy sits in the background of modern baseball in Japan like a ghostly reminder. It is the universe whispering that brilliance does not always get a happy ending. It does not even always get a full story. Sometimes brilliance is a spark in a cold wind, and the fact that it ever glowed at all is what we remember.

The arc of Sawamura’s life falls neatly across Japan’s own fractured path through the twentieth century. He was born during the First World War, found greatness during the fragile peace before the next one, and was swallowed by the machinery of the Second World War before reaching his thirtieth birthday. If Douglas Adams had created a baseball player to wander across the interstellar hazards of the 1930s and 1940s, the punch line would have landed much the same way. Genius arrives. Bureaucracy interferes. War consumes everything in its reach. The universe shrugs.

Sawamura was born on February 1, 1917, in Ujiyamada, a seaside community near the revered shrines of Ise. His father introduced him to baseball, a gift that produced a skill no one could quite explain. The boy had a clean, whip like motion, and a fastball that seemed to break laws usually reserved for physics dissertations and Vogon construction manuals. He was good enough to play at the Koshien summer tournament, which is something like sending a high schooler into a cathedral where the saints are loud and the congregation is unforgiving. Even so, he spent those years largely unnoticed, except by a handful of scouts who saw something odd in his delivery. They told each other that he had a right arm worth watching.

By 1934 he was the best young pitcher in Japan, even though his team had made an early exit from Koshien. Baseball is like that. You can lose in the bracket and still bend the future around your talent. When the Yomiuri Shimbun newspaper decided to sponsor a goodwill tour of American baseball stars, they looked for arms that could withstand the spectacle. They brought in a teenage Sawamura as part of an All Nippon team assembled to face an American lineup that read like a stack of Cooperstown plaques. This was not subtle. It was baseball diplomacy, an attempt to smooth out political tensions between the United States and Japan with line drives and polite handshakes. It was a plan destined to age as well as Vogon poetry.

Sawamura’s inclusion came at a cost. Joining the tour meant being labeled a professional, and that meant he was expelled from high school and lost the chance to attend Keio University. The edict was ironclad. Amateurs could not mix with pros. This was baseball as purity contest, and the rule is the sort of thing only bureaucrats who have never thrown a pitch in their lives could enforce with a straight face. Still, Sawamura accepted the deal. He earned a modest salary of 120 yen a month, which helped his family. He stepped away from the conventional path and toward something entirely new.

The American tour arrived that November, dragging the full reputation of Major League Baseball behind it. The lineup included Babe Ruth, Lou Gehrig, Charlie Gehringer, and Jimmie Foxx. It was the sort of gathering that should come with a warning label and maybe a barrier to keep people from standing too close. When Sawamura took the mound at Kusanagi Stadium on November 20, 1934, he was a seventeen year old boy facing giants. What happened next became the legend that defined the rest of his life.

He struck out Gehringer. Then he struck out Ruth. Then he struck out Gehrig. Then he struck out Foxx. Four Hall of Fame hitters, back to back, swinging through pitches they could not quite see and certainly could not square up. Ruth was so impressed that he told reporters the kid belonged in the Major Leagues. Connie Mack, the American manager, attempted to sign him. Sawamura refused, telling friends that he disliked the United States and could not imagine living there. There are times when history offers a fork in the road, and the man at the center takes the path that looks hardest. The universe nods and says, all right then.

Lou Gehrig eventually caught him for a solo home run in the seventh inning, but the damage was minimal. The Americans won one to zero. The box score went into the record books, but the story that lived in the public imagination was that of a teenage pitcher who had looked the greatest lineup in baseball in the eye and refused to blink. Japan embraced him. His life suddenly belonged to something larger than himself.

When professional baseball began in Japan in 1936, Sawamura joined the Yomiuri Giants, the club owned by the same media empire that had recruited him. He arrived in a league still in the process of inventing itself. Teams were experimental, the schedule was chaotic, and the idea of drawing paying crowds was still a hope rather than a guarantee. Sawamura brought credibility to the league before it had any of its own.

He was twenty years old. He pitched like a man who expected the world to answer his calls. During that first season he led the fall campaign with thirteen wins and posted an eerie 1.05 earned run average. On September 25 he threw the first no hitter in the history of Japanese professional baseball. The Giants rode his arm as if it were a locomotive and the rest of the league was late for the station. He was not fully formed yet, but the shape of his dominance was already visible.

The next year confirmed it. In the spring of 1937 he went twenty four and four with a microscopic 0.81 ERA. He threw his second no hitter on May 1. The entire season tilted in his direction. He won thirty three games, recorded a 1.38 ERA, and struck out one hundred and ninety six hitters in two hundred and forty four innings. He was named the Most Valuable Player for the spring season. He was twenty years old and had already become the standard for what a Japanese ace could look like. If baseball had been the only force moving in his life, his story might have ended differently. The game would have been enough.

But history has a habit of barging through the door without knocking. In January 1938, at the height of his power, Sawamura received his draft notice. His arm was now state property. The war in China demanded bodies, and the government did not pause to consider the value of a man’s pitching shoulder. He was assigned to the Thirty Third Infantry Regiment of the Sixteenth Division, and sent to Shanghai.

The war did not treat him gently. He became known for his grenade throwing during combat, which is an activity that produces the kind of damage a pitching coach might call career ending. The repeated overhead motion tore at the muscles and tendons in his right shoulder. It did not matter. The battlefield does not offer an injured list. In September 1938 he took a bullet in the left hand. By the time he was discharged in October 1939 he was not the same pitcher who had dazzled the world in 1937.

Even so, he came back. He returned to the Giants for the 1940 season and altered his motion to a lower sidearm delivery to compensate for the damage in his shoulder. Somehow he still managed to throw a third no hitter that July. But the physical price of his first tour continued to reveal itself. His ERA rose. His command diminished. He pitched with a body that did not respond the way it once had. He married his girlfriend, Ryoko, near the end of the 1941 season. It should have been a moment of stability.

Three days later the military summoned him again.

This time he was sent to the Philippines. He fought on Mindanao, where his experiences hardened him in ways that show up in the written fragments he left behind. He expressed contempt for American soldiers, criticizing what he called dishonorable surrenders. He was no longer simply a baseball player who had become a soldier. He was a man shaped by a brutal conflict that left little room for nuance.

In November 1943 he published a piece in a baseball magazine, a sort of memoir that served both as personal reflection and propaganda. He described a world divided along moral lines, praising the Japanese spirit while portraying the enemy as cruel and primitive. It is tempting to read his words as pure ideology, but people in war often write what they need to believe in order to keep going. A man who once struck out Ruth and Gehrig had now been pulled into a conflict that demanded different kinds of strength. His words reflected the world he had been forced to inhabit.

He returned to Japan in early 1943 and attempted to pitch again, but the effort was painful to watch. His control was gone. His velocity had vanished. He threw only eleven innings that season. His earned run average climbed to 10.64, a number that reads like a distress signal. The Giants did not renew his contract in 1944. If he had wanted to continue his career with another club, he might have had the option, but he chose to retire. His identity was tied to the team that had raised him. Leaving would have felt like surrender.

The third draft notice came in October 1944. By then the war had turned decisively against Japan. Men were being called into service with a desperation that reflected the state of the empire. Sawamura joined the reactivated Thirty Third Regiment once more. The plan was for the unit to be transported toward the Philippines, where the tide of American forces continued to advance.

He boarded the transport ship Hawaii Maru on November 27, 1944. The ship sailed through dangerous waters, and anyone familiar with submarine warfare in that period can guess the end of this sentence. On December 2 the American submarine Sea Devil found the Hawaii Maru and sent torpedoes into its hull. The ship went down off Yakushima, south of Kyushu. Sawamura was lost at sea. He was twenty seven years old.

There is an irony in his death so sharp it borders on literary symbolism. The same nation whose sluggers he had once silenced with a teenager’s fastball now sent the vessel carrying him into the deep. The sport that had linked the two countries in uneasy friendship became part of the shadow that closed around him. History is rarely tidy. It prefers edges that cut.

After the war, Japan needed heroes who could be remembered without political debate, and Sawamura filled that void. He became a symbol of lost talent, lost potential, and the cost of a conflict that devoured a generation. When the Japanese Baseball Hall of Fame was created in 1959, he was one of the first nine inductees. His number, fourteen, was retired by the Yomiuri Giants. Statues went up at Kusanagi Stadium and outside his high school in Kyoto. The ballparks of Japan carry his shadow in the way American parks carry the long echo of Gehrig’s voice.

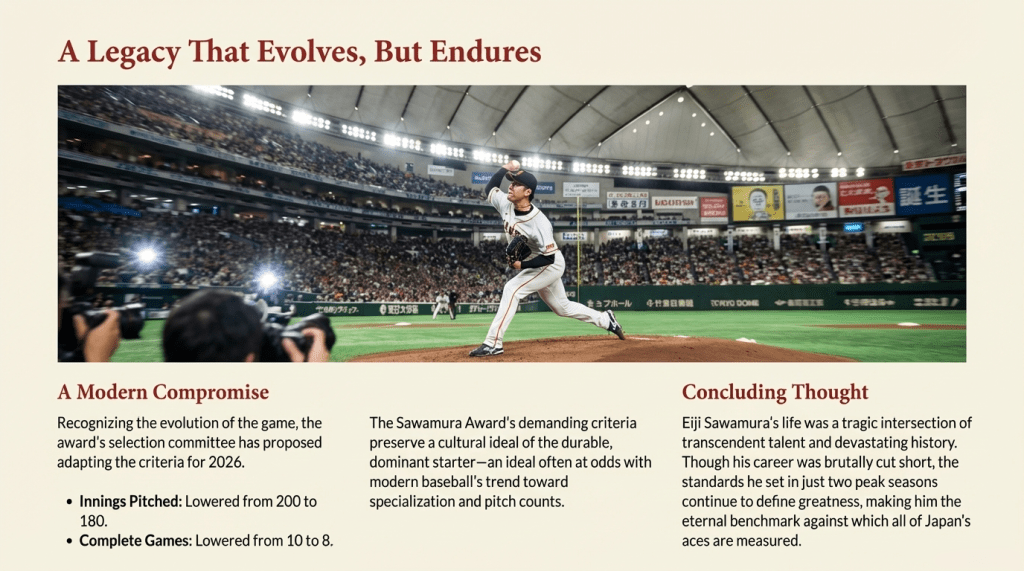

In 1947 a magazine created the Sawamura Award to honor the best starting pitcher in the league. Over time the criteria settled into a demanding set of expectations. A Sawamura worthy pitcher is meant to be a workhorse, someone capable of throwing two hundred innings, winning fifteen or more games, and carrying an ERA low enough to cause opponents to grimace. The award is not purely statistical. A committee of former pitchers votes each year, using the numbers as guidelines rather than absolutes. The spirit of the award reflects the sense that greatness is not something that happens by accident. It is something forged through durability and grit and repeated crisis. It is a nod to what Sawamura once was, and what he might have been.

His baseball career ended with sixty three wins, a 1.74 ERA, and five hundred and fifty four strikeouts. The numbers look incomplete, and that is because they are. He never got to test himself against the long arc of a twenty year career. He never faced the aging curve that bends even the greatest pitchers toward decline. Instead he was bent toward something else entirely.

The question of why Sawamura matters today has an answer that grows quietly in the margins of his story. He represents the tension between individual talent and national demand. He represents the ways in which sports can teach us about possibility, only to remind us that possibility can be curtailed by forces far outside any ballpark. His story is not a moral lesson. It is not a sermon. It is a reminder that sometimes the universe hands a young man a remarkable gift and then takes it away before anyone can figure out what it all meant.

If there is a human lesson, it is found in the fragility of the lives we elevate. Sawamura was a boy who could make Babe Ruth miss a pitch by a foot. He was a man who served three tours in a war that cost him everything. He lies somewhere beneath the waters south of Kyushu, a pitcher whose story ends without punctuation.

In a universe that rarely provides satisfying conclusions, his life is a reminder that brilliance does not guarantee longevity. It guarantees only memory. The Sawamura Award is handed out each season to remind people that once there was a pitcher who seemed capable of anything. It is a way of honoring a talent that flickered briefly, then vanished into the long night of a world at war.

If you ever watch a Japanese starter grind through a late inning in September, you might notice a familiar kind of defiance. Shoulders rolled forward. Breath measured. Eyes narrowing just enough. That is Sawamura’s ghost. He is still there in the posture of every pitcher who believes a good arm can hold the future back for one more inning. History does not allow rewrites. It only allows echoes. And some echoes never fade.

Leave a comment