There are people in history who thrive because the world applauds their talent, people who rise because their gifts demand attention, and people who manage to find their place because they are simply too good to ignore. Then there is Julia Ann Moore, who became famous for reasons so improbable that even the Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy would throw up its electronic hands, mutter something about improbability drives, and refer the reader to a separate entry labeled “Bad Poetry, American.” Moore became an unexpected cultural landmark not because she failed once or twice, but because she did so with such unshakable sincerity that failure transformed into an odd kind of triumph. She is a reminder that sometimes the universe celebrates the earnest creature who steps directly into the spotlight without realizing that the stage is a trap door.

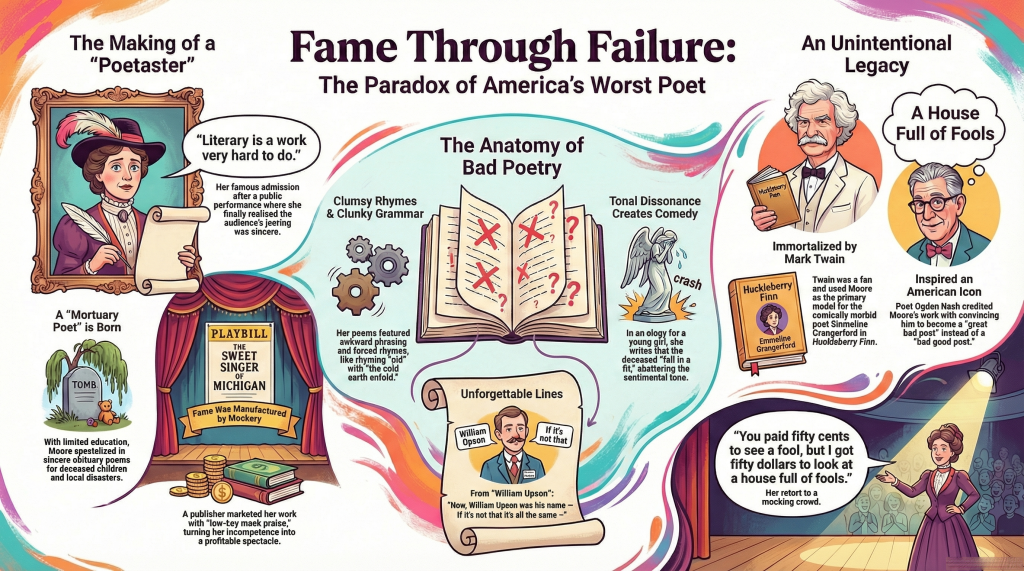

Julia Ann Moore was born in Plainfield Township, Michigan, in December of 1847. The world she came into was not one that spent much energy preserving the subtleties of poetic craft. Her family lived modestly, and like many rural Midwestern children of the mid nineteenth century, Julia’s education was brief. Her mother became ill when Julia was young, and the responsibilities of a strained household meant that her schooling effectively ended around the age of ten. That detail matters. It is the origin point of everything that followed, the reason her literary work carried the unmistakable fingerprints of a bright mind trying to write in a language she had never fully been taught. Her grammar wandered, her syntax bent itself into curious shapes, and her rhymes collided with sense in ways that left readers torn between bewilderment and laughter. The poetic term for such work was poetaster, which is a polite way of saying that the writer has attempted poetry with the tools of a carpenter and the instincts of a townsman who has never visited a library but has plenty of enthusiasm. Moore embraced the task with the kind of enthusiasm that no critic could extinguish.

She married young, at seventeen, to a farmer named Frederick Franklin Moore. Life from that point forward was a list of chores that never ended. She managed a farm, helped run a tool store, raised ten children, and kept house in the rugged cadence of rural Michigan. Six of the children survived to adulthood, which was unfortunately a better rate than many families enjoyed at the time. Her writing life developed in the quiet moments that remained after the brass tacks of daily survival were hammered flat. She worked quickly, favored ballad meter, and rarely rewrote anything. Poetry was not precious to her because her energy was spent elsewhere, yet she continued to return to it, pulled by a small persistent need to turn grief and local tragedies into verses that helped her process a world she believed to be harsh but worth understanding.

The deaths of children and neighbors reached her first through personal loss, then through the pages of newspapers. She wrote because she felt the need to mark the passage of life, and when a child died, whether hers or someone else’s, she mourned through verse. This made her part of a widespread nineteenth century phenomenon. Amateur obituary poetry filled newspapers across the country. People read these poems with solemn gratitude, and Moore was no different from hundreds of small town writers who believed their words were a service to grieving families. She became known as a mortuary poet. It sounds ghoulish, but in context it was an act of community. She was not mocking the dead. She was trying to console the living. Her poetry simply lacked the structural scaffolding that might have made it graceful.

This is where the anatomy of her poetic failure begins to solidify. Good poetry invites admiration. Bad poetry invites analysis. Moore’s work eventually became a playground for critics who delighted in the many ways verse can go wrong. Her rhythm collapsed without warning. Her lines stretched like taffy on a humid day. Her metaphors tangled into knots. Her rhymes felt as if they had been found under a bed, dusted off, and forced to participate. Yet she charged ahead, unaware that the public’s laughter was not the admiration she hoped for. Her tonal sense was fragile. What she intended as solemn would often turn suddenly comic because her diction could not carry the emotional weight she imagined.

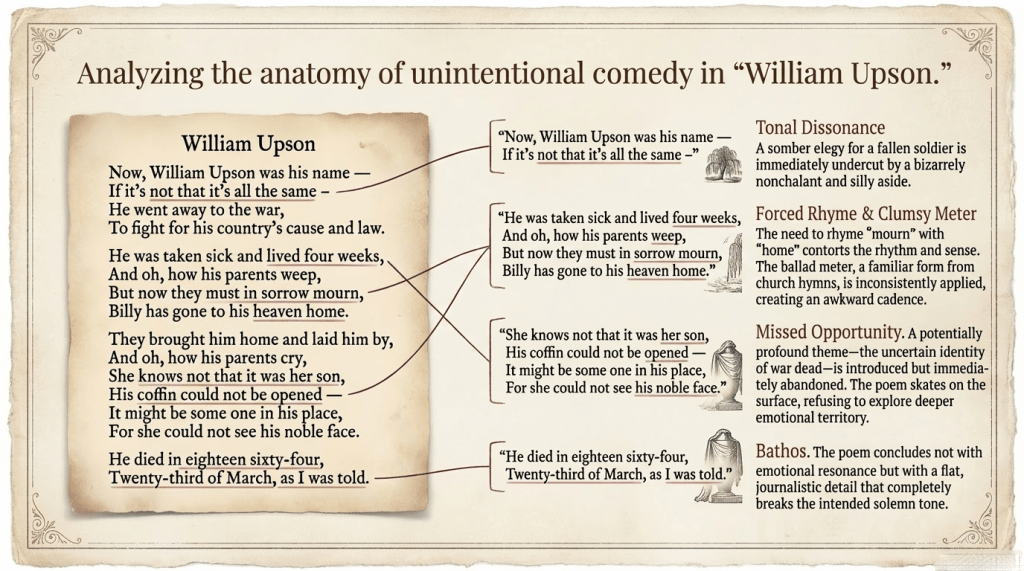

She loved ballad meter, which is familiar to anyone who has sat through a church service or memorized the theme from a certain famous mid twentieth century sitcom involving desert islands. Ballad meter provided a comforting structure. It allowed her to write quickly, which she needed, but she struggled to maintain it. A poem might begin with lines that matched the expected beats, then dissolve into irregular lengths. Five syllables here, nineteen there, then eleven for good measure. One line fell with a gentle iambic foot, the next marched with a heavy, mismatched stride. Readers stumbled across these lines as if walking across a farmhouse porch whose boards had never been measured before they were nailed down.

Her enjambment, the way she broke lines, was often arbitrary. She did not use line breaks to create tension, surprise, or flow. Instead, she broke lines because the line felt long enough, or because the rhyme demanded it, or because the poetic spirit simply told her to stop. This created a choppy rhythm that could turn a straightforward sentence into something unintentionally whimsical. In an effort to rhyme, she often twisted syntax until it no longer resembled conversational English. Common phrases became inverted or contorted, which created comedic effects she never intended.

Her rhymes themselves were enthusiastic but clumsy. She matched words that did not rhyme at all, or forced lines into unnatural shapes to make them rhyme. She would invert sentences, stretch meanings, and insert unnecessary words simply to land on a rhyme that was still questionable. “Little Charlie Hades” is remembered partly because she rhymed “old” with “the cold earth enfold,” producing an awkward phrase that sounded as if it had escaped from a schoolbook printed with crooked type. She also favored what reviewers called just miss rhymes, where the words were nearly right, but not quite. It was as if she had been handed a rhyming dictionary assembled by someone who had never heard human speech.

Then there was the narrative dissonance. She intended pathos, yet achieved bathos. Hattie House, a sentimental elegy for a young girl, includes the line that the poor child “fell in a fit.” The moment was meant to be reverent, yet came across as a police report. She wanted to comfort the bereaved, yet her choice of words often introduced a chilling literalness. In The Ashtabula Disaster, a poem about a real train accident, she described the horror by saying that “despair was right and left.” The phrase reads less like poetry and more like someone describing the scene to a clerk at a general store while buying lamp oil. The mismatch between her sincerity and her word choices made these lines unintentionally comic, yet the humor was rooted in the jarring contrast between intention and execution.

“Sketch of Lord Byron’s Life” demonstrates the full array of her difficulties. She attempted to summarize the career of one of England’s greatest poets, a task that would intimidate even a seasoned writer. She began by admitting uncertainty about whether Byron was truly a poet, then pressed forward with phrases that fought each other from line to line. The meter wandered, the syntax buckled, and the rhyme insisted on marching in directions the rest of the sentence refused to follow. The poem has been described as a minor catastrophe, which is not entirely fair. It is more like a sincere attempt to build a carriage using only the drawings of someone who once glanced at a carriage from across a field. One cannot fault her enthusiasm, only her sense of proportion.

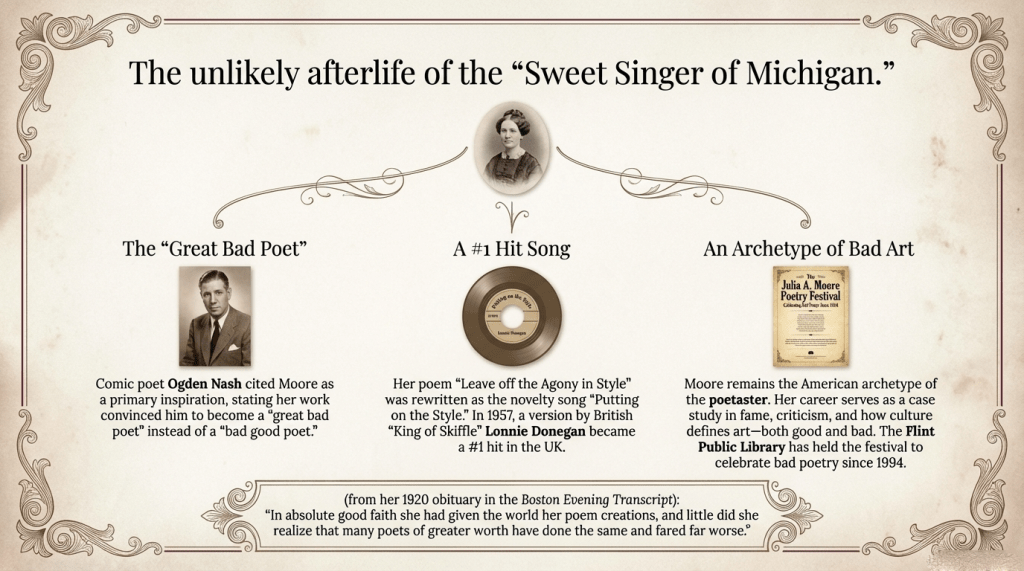

Her first published book, The Sentimental Song Book, appeared in 1876. Local readers purchased it eagerly because the poems spoke to familiar events. Cleveland publisher James F. Ryder saw an opportunity and bought the rights. Ryder recognized that bad verse could be profitable if packaged correctly. He prepared a national edition titled The Sweet Singer of Michigan Salutes the Public, and he sent out review copies with cover letters filled with arch humor. His praise was low key, but the tone suggested to reviewers that they were being invited to witness something entertainingly dreadful. The reviewers obliged. They responded with affectionate ridicule, joking that Shakespeare would be relieved to have died before reading it.

The book became a curious best seller, which is a polite way of saying that many people purchased it simply to laugh at it. The laughter did not bother Moore at first, partly because she did not recognize it. Her mind did not interpret mockery as insult. She assumed the public treated her work with the same earnestness she gave to it. For a time, that misunderstanding softened the blow.

The Powers Opera House in Grand Rapids hosted one of her most famous public readings in 1877. She stepped onstage expecting a respectful audience. The crowd responded with jeers, laughter, and general amusement at her expense. She believed they were mocking the orchestra rather than her, which says something about the protective bubble she carried with her. That evening became part of her legend. She finished the reading without realizing that she was the subject of the audience’s merriment.

Her next public reading, in December of 1878, was different. She felt the tone change. The crowd mocked her openly, and she finally understood they were laughing at her rather than her poems. Something shifted in her that night. The hurt turned to defiance for a brief moment. She snapped back at them, saying that they had paid fifty cents to see a fool, while she had been paid fifty dollars to look at a house full of fools. It was not the line of a shrinking poetaster. It was the line of a woman who had lived hard years and put up with more than her share of nonsense.

Her second book, A Few Choice Words to the Public, included a defensive essay in which she pushed back against her critics and accused them of slander. The book did not sell well. Her husband Fred insisted she give up publishing entirely after the humiliation of the 1878 performance. From that point forward, her public career diminished. She withdrew from the stage and the literary world, and in 1882 the family moved north to Manton, Michigan, where anonymity offered a kind of shelter. The townspeople respected her and protected her privacy, even when reporters tried to track her down. She reinvented herself as a businesswoman, running a store while Fred operated a sawmill and orchard. Her poetry survived in private notebooks rather than public pages.

She continued writing privately, and after Fred’s death in 1914 she republished a prose work titled Sunshine and Shadow in pamphlet format. She died quietly in 1920. The Boston Evening Transcript noted that she had created her poems in absolute good faith. That phrase captures the entire essence of her life. She did not aim for greatness. She aimed for sincerity. The world read her failure as comedy, yet she never intended a joke.

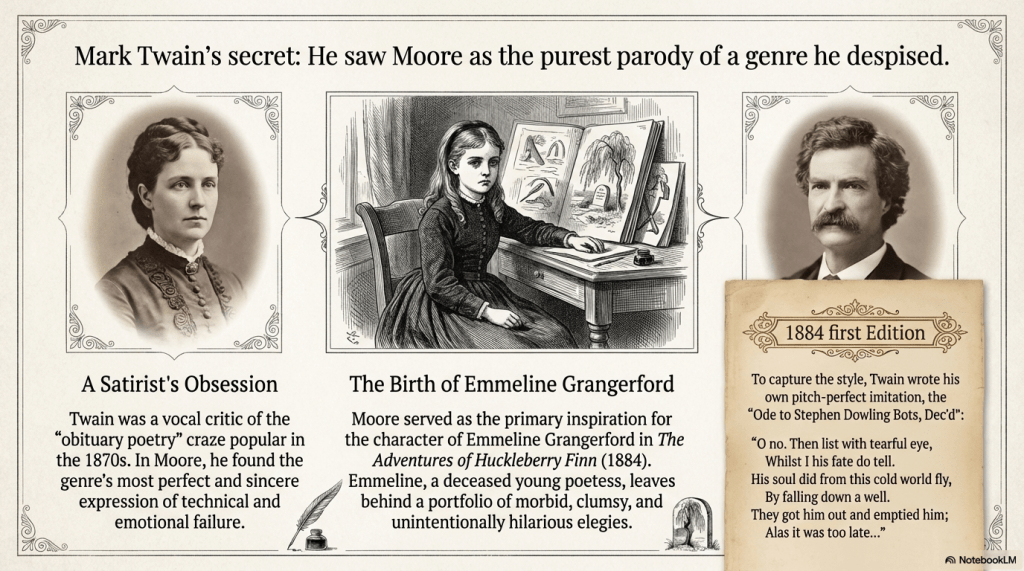

Her legacy is a curious one. Mark Twain admired her. It is tempting to believe that a sharp satirist like Twain enjoyed her work only for its faults, but there was more to it. Twain liked the way her sincere attempts at pathos became unintentionally funny. He used her as the model for Emmeline Grangerford in The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, the morbid poet who scribbles heartfelt yet dreadful verses about the recently deceased. Emmeline’s poems in the novel serve as a gentle indictment of sentimental obituary verse. Twain recognized that Moore represented an entire genre, one that tried to offer comfort through poetry but often collapsed under its own sentiment.

He even wrote a poem in her style, “Ode to Stephen Dowling Bots, Dec’d,” which mimics the imprecise diction, mangled meter, and earnest sorrow she brought to her work. Twain understood that Julia Moore was something unique. She had created a body of work so entirely free from irony that it became the ideal tool for expressing satire. That kind of purity is difficult to manufacture. It has to happen naturally.

Moore is often compared to William McGonagall, the Scottish weaver turned poet who has been called the worst poet in the English language. The comparison is fair in some ways and unfair in others. Both had unshakable confidence in their ability, both lacked formal training, and both produced poetry that violated the basic expectations of rhythm and diction. Yet they differed in important ways. McGonagall’s flaw was rigidity. His meter marched with heavy boots that never changed pace. His verses had the humorless monotony of a grandfather clock that only chimes wrong notes. Moore’s flaw, by contrast, was chaos. Her poems never stayed in one place long enough to become predictable. Her lines jumped unpredictably, her syntax bent itself into uncomfortable shapes, and her meter obeyed no rule for longer than a line or two.

She has been grouped with the Western Michigan School of Bad Versemakers, which includes J. B. Smiley and Fred H. Yapple. These poets created verse so unsteady that critics have treated them like geological curiosities. Their work speaks to the people who had no access to sophisticated literary education but felt compelled to write anyway. They represent a democratization of poetry. Anyone could write, whether or not they knew how.

Julia Moore remains a fascinating example of what happens when sincerity meets limited resources. Her failures were complete enough to become memorable, yet never cruel or contrived. They speak to something human. She wanted to comfort families and honor lives. She attempted poetry because she felt called to it, not because she expected fame. Her poems capture the voice of a rural community that grieved in rough, unpolished ways. In an era obsessed with polish and refinement, her lack of technique became unforgettable.

Her immortality rests not on talent but on earnestness. There is something refreshing about that. Plenty of technically competent sentimental poets have faded into obscurity. Their lines were passable but unremarkable. Moore endures because she offered something raw and unexpected. She demonstrated that the boundary between folk expression and professional literature is a fragile one. Poetry requires a steady hand, yet emotion will push through even the most unsteady lines.

Her life tells a story of a woman who believed in the power of words, even when they wandered off in directions she never intended. She reminds us that failure, when pursued with total sincerity, can become its own form of success. There is something almost cosmic about that truth. It fits nicely in a universe where improbability drives starships, where the worst poetry in the galaxy can clear a room faster than an airlock malfunction, and where a Michigan farm woman with only a few years of schooling can become a permanent fixture in American literary history because she tried, wholeheartedly, to say something kind.

That is the contradiction that makes Julia Ann Moore worth remembering. She stands as a testament to the human impulse to create, even when skill is in short supply. She believed her poetry served a purpose, and in the end she was right. It has outlived the critics, outlived the fashions of her day, and now sits in the long corridor of cultural memory, humming quietly to itself with the determination of a woman who believed that every life deserved a verse. She wrote in absolute good faith, and sometimes that is enough for history to take notice.

Leave a comment