November has always behaved like a month with an old soul, the sort of calendar neighbor who sits on the porch as the leaves finish falling and tells you quietly what you already know. There is more year behind us than ahead. The light is thinning. The animals have figured this out without any fuss, but people are slower on the uptake. We insist on taking stock, on telling ourselves we are ready for what comes next, even when we are not. November has always been the place where reckoning and resolve meet. The Romans sensed it. Medieval farmers sensed it. The twentieth century all but shouted it. You live long enough and you begin to see that November is not simply a matter of thirty days. It is a way of thinking.

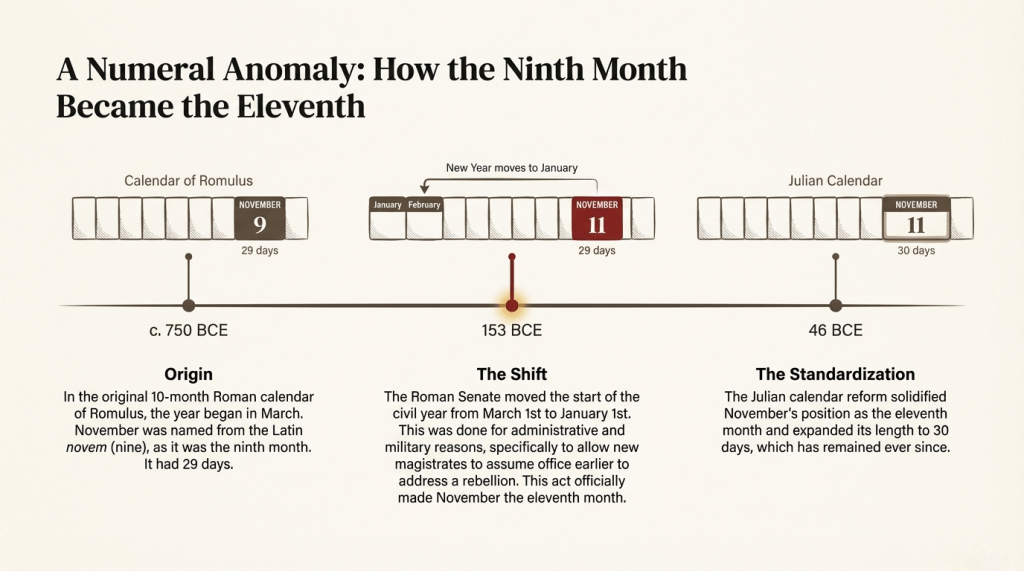

Of course, November began with a numerical mistake. The Romans named it for the word novem, which means nine. It made perfect sense in the earliest Roman calendar, the one that started in March and treated winter as a vague period outside of time. November was the ninth month of that strange ten month experiment. The Romans built early calendars with the enthusiasm of engineers who knew their system was not entirely sound but hoped the thing would not fall apart before they had a chance to fix it. The result was predictable. By the third century before Christ the whole arrangement slipped so badly out of alignment that even Roman officials threw up their hands. Something had to give. What gave was the beginning of the year. Instead of waiting for March, they moved the new year to January, which pushed November into the eleventh position where it sits to this day, still carrying a name that points to a number it no longer represents.

The calendar drifted again. Julius Caesar, who loved precision when it suited his needs, imposed the Julian reform and stretched November into the shape we recognize now. Thirty days, no more and no less. Pope Gregory XIII finished the work many centuries later. He corrected the accumulating astronomical wobble, tuned the year more closely to the sun, and delivered our modern system. Through all that tinkering no one bothered to rename November. The word had sunk too deeply into the cultural ground. Names have a way of outlasting the reasons behind them. Rome could rise or fall and November would still be November.

For all its administrative reshuffling, November had a personality in Rome. It was the month of the Plebeian Games, a long public festival of theater, sport, and spectacle that ran from the fourth to the seventeenth. It belonged symbolically to Diana, the guardian of the hunt who watched over the closing of the agricultural season. Artists sometimes associated November with Isis, whose festival ended on the third and whose reach extended throughout the Mediterranean world as Rome expanded. Roman writers advised farmers to get their wheat and barley sowed, check their orchards, and make sure the trenches around the trees were cleared before the deeper cold arrived. Every instruction had the same underlying message. Winter is coming. Prepare.

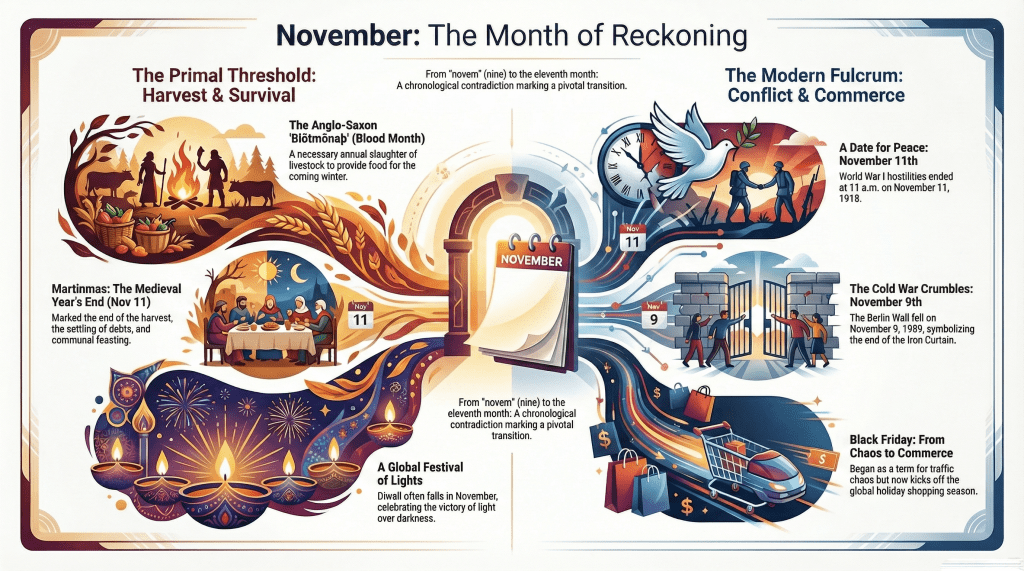

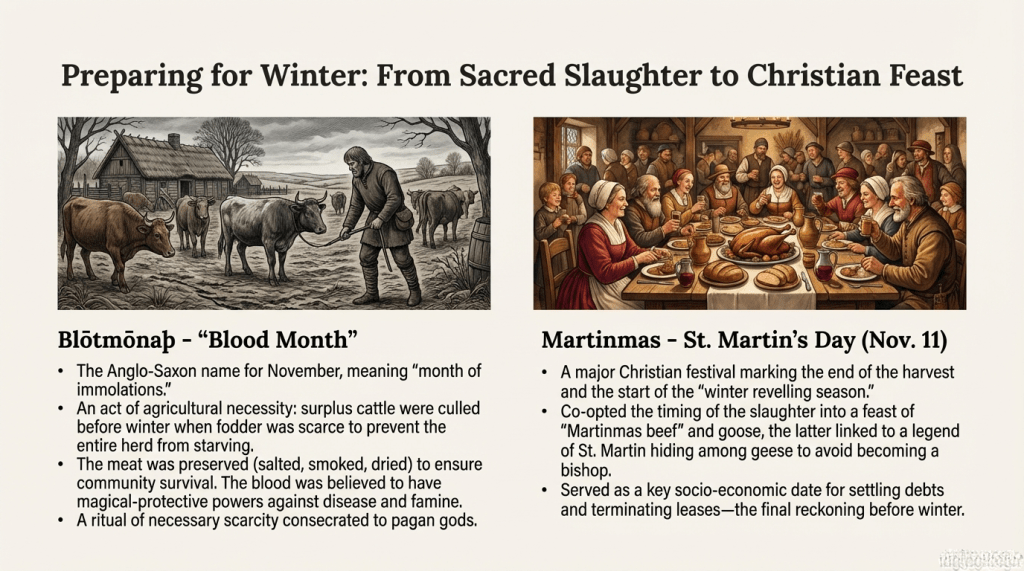

This theme carried well beyond Rome and into the more northern reaches of Europe where seasons narrowed into harsh binaries. Winter and summer were the main divisions in many ancient calendars, and November marked the point where the balance tipped decisively toward the dark. In Old English it was called Blotmonath, the month of blood, a name that strikes modern ears with a blunt honesty our own age sometimes avoids. To the Anglo Saxons this period involved the necessary slaughter of cattle. You kept the animals that could survive the winter. The others became food, tallow, leather, and ritual offerings. Bede wrote that these slaughters were consecrated to the gods, which should remind us that survival once carried the weight of ceremony. People did not draw sharp lines between the practical and the spiritual. If anything, they understood better than we do that the sacred and the ordinary lived very close together.

The beginning of winter brought Martinmas, the feast of Martin of Tours, on the eleventh. In many parts of Europe it served as the last great pulse of warmth before the cold took hold. It was the day when geese were roasted, lanterns carried, and communities acknowledged the shift into the season of reckoning. Martin himself was a soldier who cut his cloak in half to share it with a beggar, a gesture so old it borders on myth, but the day that took his name had roots reaching into pre Christian winter festivals. In Scotland Martinmas marked a legal turning point when rents came due and leases turned over. It was a hinge day in a culture that recognized the practical realities behind any feast. Celebration does not erase the ledger, it simply reminds you that the ledger exists.

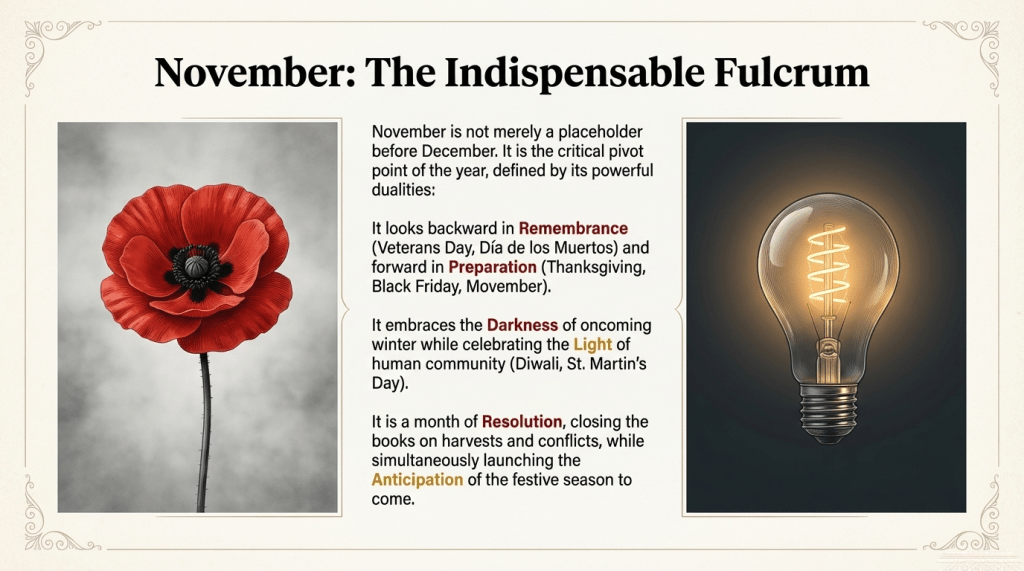

The older Celtic world held its own understanding of this threshold. Samhain, falling at the turn from October to November, marked the end of the harvest and the start of winter. The living and the dead were believed to reside near one another. Fires were lit to honor the shifting of seasons and to ease fears about the unknown. When Christianity spread across those lands it adapted the calendar, turning the first and second of November into All Saints and All Souls. The echoes of the older beliefs never fully disappeared. They settled into the rhythm of the month, part of that uneasy blend of memory and obligation that has always made November feel heavier than the months around it.

Other cultures shaped November in their own ways. In Mexico the first days of the month became the Día de los Muertos, a time when families honor the dead with altars, offerings, and gatherings that are anything but morbid. It is a holiday that treats death with a kind of direct honesty, neither trivializing grief nor fearing it. Scholars have long debated the extent to which these celebrations stem from pre Columbian observances, but the outcome needs no debate. November became a space where the living acknowledge the ones they miss.

In Asia the Hindu festival of Diwali sometimes lands in November, spilling light into the dark season. Jains and Sikhs observe it as well. Sikh communities also remember the martyrdom of Guru Tegh Bahadur in late November and celebrate the birth of Guru Nanak earlier in the month. Many Christian communities begin their Advent preparations as November draws to a close. Different traditions, different geographies, different histories, yet all drawn toward the same seasonal truth. Darkness is deepening. Something must be kindled against it.

It would be a mistake, though, to think of November as merely a container for spiritual observance. It has also been the stage for turning points that shaped the last century. At the eleventh hour of the eleventh day of the eleventh month in 1918 the guns of the First World War finally fell quiet. That phrase has become so familiar that people forget how carefully it was arranged. The ceasefire had been signed hours earlier, but both sides agreed to halt fire at a moment that sounded poetic. It created an anniversary that governments could uphold and grieving families could mark. President Wilson called the first Armistice Day one year later, hoping the world had learned something from the carnage. Many hoped he was right. The next decades proved otherwise.

After the Second World War the United States struggled with how to observe the date. Armistice Day honored one generation of soldiers, but another had just returned from battlefields in Europe and the Pacific. President Eisenhower signed the law that transformed Armistice Day into Veterans Day in 1954. The observance expanded to include all who served, not only those who fought in the Great War. Congress tried to shift the holiday into October during the long experiment with Monday holidays in the late 1960s. It did not take. President Ford signed the act that returned it permanently to November 11. Some dates are too deeply carved into memory to be moved without consequence.

In 1989 another November moment reshaped the modern world. Crowds gathered at the Berlin Wall on November 9, spurred by political confusion, mass protest, and sheer determination. When the first East Germans crossed almost unhindered, the symbolism swept through the city like a clean wind. The Wall had defined an era. Its breach marked the beginning of the end for a divided Europe. It is tempting to view the fall as inevitable, but inevitability is a luxury only available in hindsight. To those who lived behind the concrete and wire it was a moment when history finally exhaled.

Even events in November that seem lighter on the surface have deep roots. Thanksgiving in the United States carries more complexity than its comforting imagery suggests. The fourth Thursday of the month, fixed by Congress in the early 1940s, is now a day of football, turkey, and family tables. Yet the national holiday owes its existence to Sarah Josepha Hale, a persistent nineteenth century editor who spent decades urging the nation toward a single day of gratitude. Her vision was domestic and unifying. It found its moment during the Civil War when Abraham Lincoln proclaimed a national day of thanks in 1863. The story Americans came to associate with that holiday, the Pilgrims and the Wampanoag, was woven into the national fabric much later. What happened in 1621 was not called Thanksgiving by the participants. It was a harvest feast. The meaning attached to it grew in fits and starts as the country searched for common stories.

President Roosevelt tried to nudge Thanksgiving earlier during the Great Depression, hoping retailers would benefit from an extended holiday shopping season. The idea met with mixed reactions. People are careful with traditions. They do not always appreciate rearrangements designed to boost commerce. Congress stepped in and set the date where it remains. Some Native Americans observe the holiday as a day of mourning due to the violence and dispossession that followed European settlement. November rarely lets anyone settle into easy myths. It has a way of reminding us that every national story carries shadows.

The day after Thanksgiving has grown into a cultural phenomenon of its own. Black Friday began as a rather sour phrase used by Philadelphia police who dreaded the traffic, crowds, and general disorder that accompanied the rush of shoppers arriving for the weekend of the Army Navy football game. Retailers eventually embraced the name and tried to attach a more cheerful explanation to it. They claimed it represented the day when stores moved from deficit to profit. The public liked that version better. Commerce often thrives by sanding down the rougher edges of its own origin stories. With the rise of online shopping the month added Cyber Monday, a term invented in 2005, and with it an extended ritual of sales, promotions, and inbox clutter.

November has also become a busy month for public health campaigns. Movember, which started as a small gesture among friends in Australia, grew into a worldwide effort to raise awareness about prostate cancer, testicular cancer, and mental health. The idea is simple. Grow a mustache. Start conversations. Raise money for research and care. Other causes mark the month as well, including pancreatic cancer, lung cancer, diabetes, and prematurity. Social observances run alongside them. The United States recognizes Native American Heritage Month. The twentieth marks the Transgender Day of Remembrance. The twenty fifth is the International Day for the Elimination of Violence Against Women. These dates sit within the larger landscape of modern advocacy, reminders that November is never content to pass quietly.

The symbolic language woven through the month reinforces its character. People born under Scorpio or Sagittarius claim one or the other as their zodiac territory, and jewelers remind us that topaz and citrine belong to November. The chrysanthemum is the birth flower, the sort of detail that seems trivial until one learns how often chrysanthemums appear in cultural rituals around the world. Nothing in November arrives without inheritances.

So what does all of this add up to. A month that began as the ninth and became the eleventh. A month that signaled slaughter, sacrifice, and survival. A month that watched saints honored, wars ended, and walls crumble. A month that holds gratitude, mourning, celebration, and exhaustion in the same pair of hands. November’s identity seems contradictory because human communities are contradictory. We need harvests and we need memorials. We need feasts and we need silence. We need to face what has happened in the year and brace ourselves for what comes next.

There is something deeply human about this. Ancient farmers knew the winter demanded preparation. Warriors who survived the trenches understood that dates matter long after the bodies are buried. Berliners who chipped at the wall with hammers in 1989 knew what it meant to reclaim a future. Families who gather at Thanksgiving tables know the history of their own households, with all their frayed edges, joys, and disappointments. Advocates who mark awareness days know the effort to repair the world never quite ends. November carries these truths without ornament.

You do not have to romanticize the past to appreciate how earlier generations read this month. They saw the thinning sunlight, the frost rising on the edges of the fields, the sky settling into its winter posture. They felt the pull toward memory. They understood that the end of the year is rarely a simple matter of days ticking by. It is a reckoning. Sometimes gentle, sometimes not. Always honest.

Every calendar year needs an endcap, something that pulls the strands together and reminds you that existence does not run endlessly forward without pause. November has filled that role across cultures and eras. It sits between harvest and winter, between conflict and resolution, between loss and renewal. People have tried to shape it with festivals, laws, commemorations, euphemisms, bargains, and superstitions. None of these quite tame it.

The older I get, the more I respect this month. It does not flatter. It does not rush. It does not pretend that the world is simpler than it is. November stands in the doorway of the year and tells you quietly that endings matter. Not because they close things. Because they prepare the ground for whatever comes next.

Leave a comment