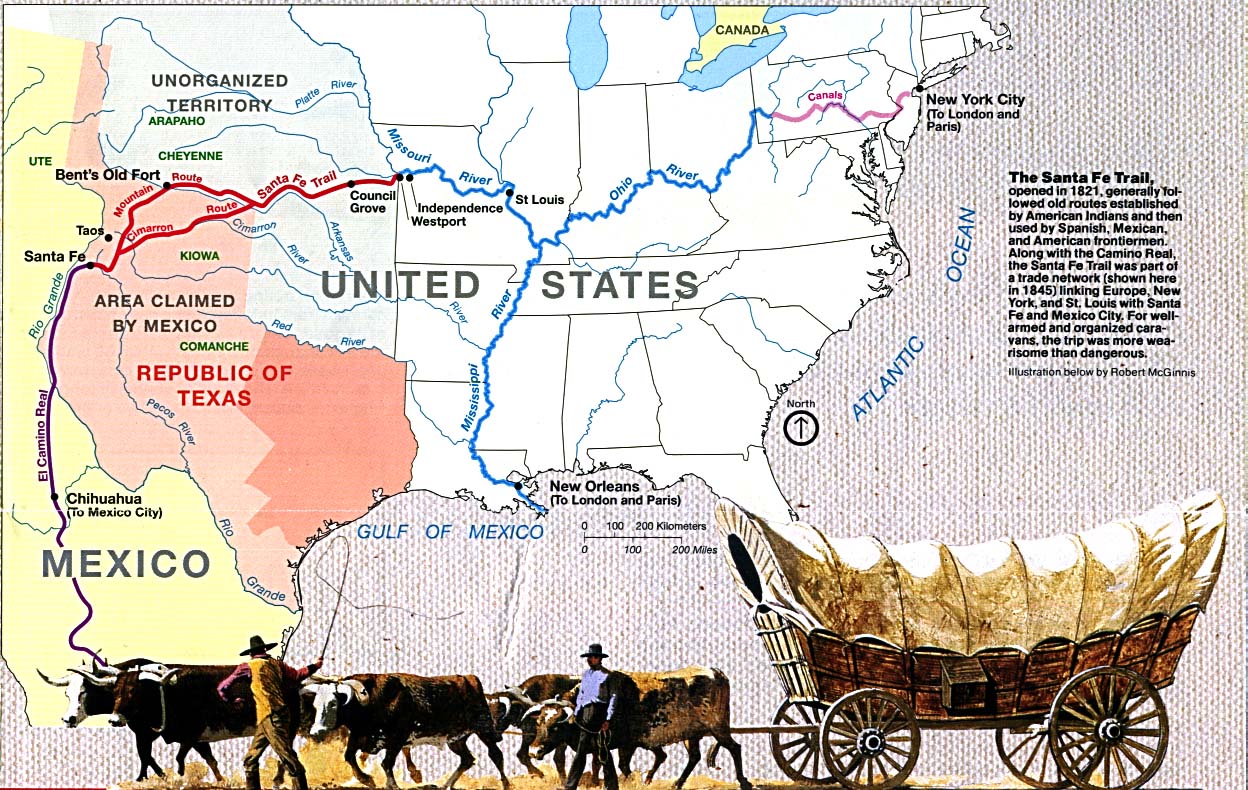

The Santa Fe Trail was not a trail of settlers or homesteaders but of traders and opportunists. It ran not toward farmland but fortune, across a wide prairie that seemed endless and indifferent. Long before wagon wheels carved its ruts, the region between Missouri and Santa Fe had been a closed frontier. Under Spanish colonial law, foreign trade was forbidden. Goods reaching New Mexico traveled a grueling sixteen hundred miles from Veracruz along El Camino Real de Tierra Adentro, arriving so burdened by expense that ordinary items like calico and cotton cloth sold for up to three dollars a vara, a Spanish yard, prices that left the population desperate for cheaper merchandise. When Mexico gained independence in September 1821, that barrier vanished overnight and the gates to commerce opened wide.

William Becknell, a war veteran and struggling merchant from Franklin, Missouri, was among the first to sense the opportunity. Drowning in debt, he gathered a small party and set out in September 1821 with about three hundred dollars’ worth of goods, intending to barter for horses and mules or whatever might sell in the new republic. He and four companions crossed the plains and reached Santa Fe on November 16, 1821, the first American traders to arrive under the new Mexican flag. Their welcome was friendly and the profits astonishing. Becknell’s modest stock of cotton cloth and calico sold for about three dollars a yard, and his three-hundred-dollar investment returned roughly six thousand in silver. He had not just cleared his debts; he had discovered a road to prosperity. His return to Missouri electrified the frontier. Newspapers marveled at the sudden wealth, and within months he was preparing to go back, this time not as a debtor but as a pioneer of commerce.

In the spring of 1822 Becknell planned his second journey. If the first expedition proved that trade was profitable, the second would test whether it could be sustained on a larger scale. The key was transport. Pack animals had limited capacity and were slow. To move significant freight, Becknell chose wagons. It was a bold gamble. No one had yet driven wheeled vehicles across the Great Plains to New Mexico. Roads were little more than faint traces, rivers unbridged, and the prairie itself an ocean of grass with few landmarks. Yet Becknell saw wagons as the future. In May 1822 he departed Franklin with about thirty men and roughly three thousand dollars’ worth of goods loaded into three mule-drawn wagons, the first wagon train to attempt the Santa Fe run.

The wagons themselves were sturdy, broad-tired vehicles built for freight rather than speed. They creaked westward across the plains, their iron rims biting into tallgrass that reached the hubs. It was a scene no one on the frontier had witnessed, wagons heading not north or east but into the unknown southwest. Becknell’s small caravan was the first to cross the plains with such vehicles, setting the pattern that later traders and explorers would follow, men like Jedediah Smith and William Sublette, whose journeys would widen America’s knowledge of the West. But Becknell’s wagons proved the concept first, long before there was a map or a proper name for the route.

From the Missouri frontier they followed the familiar line of the Arkansas River, heading toward the mountains. Then Becknell made a fateful decision. To shorten the journey, he left the river and struck southwest across a vast, dry plain toward the Cimarron River. The route promised a quicker path to Santa Fe but offered no guarantee of water. Later generations would call it the Cimarron Cutoff. At the time, it was simply a gamble, one that nearly cost every man his life.

For two days the wagons rolled across a landscape travelers called the “water scrape.” The sun blazed down from an empty sky. The air shimmered. Canteens ran dry, and the prairie wind offered no relief. The third day brought panic. Men staggered, horses collapsed, and even the mules could barely lift their heads. Desperation turned savage. They slit the throats of their dogs and even cut the ears of their mules, hoping the warm blood might moisten their mouths. It only inflamed their thirst. In the confusion, men wandered from the party, some collapsing in the dust. At that moment of near ruin, providence intervened. A lone buffalo appeared, trudging up from a shallow draw, its sides heavy and wet. The men shot it and found its stomach full of muddy water drawn from the Cimarron. They drank it greedily, “as nectar from paradise,” then followed its trail to the river itself. There they filled their canteens and returned to rescue the comrades they had left sprawled on the plain. The Cimarron Cutoff had nearly destroyed them, but they had proved it could be crossed.

Once the immediate crisis passed, the expedition recovered quickly. They followed the Cimarron downstream, reached more forgiving country, and pushed on to Taos, roughly seventy miles north of Santa Fe. From there they descended the valley of the Rio Grande and arrived in late 1822 after about forty-eight days on the trail. This was the first successful wagon crossing of the plains to New Mexico. Although the precise date of arrival is uncertain, it marked a turning point in western commerce. The people of Santa Fe marveled at the wagons themselves, iron-shod behemoths that had somehow crossed the desert. The goods they carried sold readily, and even the wagons fetched astonishing prices. One that cost about one hundred fifty dollars in Missouri sold for seven hundred in Santa Fe. Becknell’s entire cargo of about three thousand dollars reportedly brought in around ninety-one thousand, a profit margin so large it entered frontier legend. Even if the number is approximate, there is no doubt the returns were spectacular. The wagons had made the trade not only possible but immensely profitable.

Becknell’s success contrasted sharply with earlier failures. A decade before, in 1812, a party led by Robert McKnight, James Beard, and others had tried to reach Santa Fe but were seized by Spanish royalists and imprisoned in Chihuahua for nearly nine years. Under Mexico’s new independence, those dangers vanished. Becknell’s experience proved that trade could flourish openly and legally, and that wagons could carry far more goods at far lower cost. What began as an experiment now became an enterprise.

Although wagons were absent from the trail in 1823, their feasibility had been proved. In 1824, a large caravan of twenty-five wheeled vehicles, two heavy road wagons, twenty Dearborn carriages, and two carts rolled from Missouri with cargo worth twenty-five to thirty thousand dollars. Two years later, by 1826, Josiah Gregg recorded that about sixty wagons made the run to New Mexico and that from that time forward, pack animals were abandoned in favor of wheels. Within a few seasons the Santa Fe Trail had transformed from a narrow traders’ path into a broad, deeply rutted road of commerce.

The trade’s scale soon drew the attention of Congress. In 1825 lawmakers authorized a federal survey to mark and secure the route between Missouri and the Mexican border. Becknell himself assisted the commissioners, lending his knowledge of the prairie and its scarce water sources. That same summer, U.S. representatives concluded treaties guaranteeing safe passage: on August 10 1825 with the Great and Little Osage at Council Grove, and on August 16 1825 with the Kansa at Dry Turkey Creek. Both agreements granted citizens of the United States and of Mexico the right to travel unmolested along the road. These measures gave the Santa Fe Trail an official status as a recognized highway of international commerce, protected, at least on paper, by law and treaty.

For his role in proving and mapping the route, William Becknell came to be known as the Father of the Santa Fe Trail. It was a title earned, not bestowed. His wagons had demonstrated that the great plains could sustain regular freight transport, that merchants could rely on a fixed road, and that the economies of two nations could meet halfway across a wilderness once thought impassable. The trail became the backbone of trade between Missouri and New Mexico for nearly sixty years. Along it rose towns, stage stations, and military posts. Caravans learned to travel in large armed groups to guard against Comanche raids. Forts Leavenworth, Larned, and Union sprang up to protect the traffic. The trail was not just a road of goods but of influence, carrying language, religion, and custom between two cultures that had once been strangers.

By the 1850s the Santa Fe Trail had grown into a grand artery of civilization. Its caravans were enormous, hundreds of ox-drawn wagons loaded with hardware, textiles, and machinery bound for markets beyond the Rio Grande. By 1860, more than three thousand wagons, nine thousand men, and twenty-eight thousand oxen were hauling about five million dollars in merchandise across the plains each year. The wagons, called “prairie schooners” for their canvas tops, moved like a slow-rolling fleet through seas of grass, linking the Mississippi Valley to the mountains and deserts of the Southwest.

The trail endured until the coming of the railroad. In 1880 the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe reached the old capital, and the era of wagon freighting ended. But the memory of the trail lingered, etched into the land and the nation’s imagination. Alongside the Oregon and California Trails, it became one of the three great paths across the trans-Mississippi West, each representing a facet of the American spirit. The Oregon Trail spoke of settlement, the California Trail of ambition, and the Santa Fe Trail of commerce.

William Becknell’s legacy lies not only in the ruts that still scar the prairie but in the idea that built them. He showed that the wilderness could be conquered by trade rather than by arms, that endurance and ingenuity could transform isolation into exchange. His 1822 expedition, nearly lost to thirst, saved by the providence of a buffalo, and crowned with improbable success, proved that civilization could move not just on foot or horseback but on wheels. The trail he opened connected nations, created wealth, and helped shape the character of the American frontier. What began as one man’s desperate attempt to escape debt became the genesis of a commercial highway that carried the nation’s enterprise across the plains and into history.

Leave a comment