You can dress a ship in brass and bunting and call her safe, but the sea is an unforgiving bookkeeper. It tallies every shortcut and comes calling when the ledger runs red. The SS Vestris sailed out of Hoboken on the afternoon of November 10, 1928, as if routine could ward off reality. Within forty-eight hours, that confidence had been rolled flat by gray Atlantic seas, bad decisions, and a culture more concerned with appearances than seamanship. The wreck never became a tourist myth or a Hollywood hymn. It became something harsher. A cautionary story about how ordinary negligence kills ordinary people in extraordinary ways, and about how reform is almost always written in the handwriting of loss.

She was a product of the last gilded years before the guns of August broke the world. Workman, Clark & Co. of Belfast laid her down as yard number 303, one of Lamport and Holt’s “V-class” liners, mid-sized steamers named with a whimsical nod to artists and engineers whose names began with that letter. At 511 feet overall and roughly 10,500 gross tons, Vestris was built for steadiness rather than speed, making about fifteen knots on a pair of 4-cylinder, quadruple-expansion engines that drove twin screws. Her pamphlets sold a civil passage to and from the River Plate, with 280 berths in first class, 130 in second, and another 200 in third, tended by a crew of around 250. She launched May 16, 1912, and made her maiden voyage that September from Liverpool to the River Plate, quickly shifting to the New York–South America run, via the Caribbean, where Lamport and Holt liked to say they offered the largest and most comfortable ships on the route.

For the Children Who Sleep – Words and Music by Dave Bowman © 2025 by Slippery Fish Entertainment

Like many liners of her generation, Vestris wore a uniform that included war service. She was chartered as a troopship during the First World War, and in 1919 endured a nasty coal bunker fire that had to be fought for days, with a Royal Navy escort nursing her to Saint Lucia for final extinguishing. The incident did not scrap her. She was repaired and sent back to work. The postwar years found her rotating between New York, Liverpool, and South American ports on a triangular circuit that kept the company’s flag in the papers and cargo in the holds.

By November 1928 she was not new. She was also not, by all accounts, properly prepared. The load line rules were not matters of taste. They were born of bitter experience. Before she sailed on November 10, several things were not done that should have been. Her ballast tanks were not pumped out. The hatches of her coal bunkers were not properly battened and secured. She rode deep. Investigators would conclude her saltwater draft stood at 26 feet 11 and a half inches, deeper than the lawful marks that kept a margin between prudence and hubris. Some witnesses said she showed a slight list even as she worked down the river, a complaint brushed aside as the nervous talk of landsmen. Complacency is a quiet killer.

The ship cleared the coast and put her bows toward the River Plate. A November gale in the North Atlantic is not a rare beast. You do not need drama to do damage. By the morning of Sunday the 11th, a hard northeast blow was rolling heavy water over Vestris’s decks. Somewhere low on her starboard side, a coal port sat partially open. Four feet above the waterline is far too close when the sea is climbing stairs to knock. Water found the gap. Coal shifted. Cargo shifted. The ship began to lean, the way a proud man leans when the first drink goes down wrong. Passengers noticed. In the dining saloon they held their plates like nervous acrobats. Fred W. Puppe, traveling with his wife and infant to a new job in Buenos Aires, would later tell a federal inquiry about the ship’s steady tilt, the invisible steward assigned to his cabin who was too drunk to work, and the absurd, chilling reassurances that all of this would be straightened out in an hour. It was not straightened out. It was not even handled. The sea will treat you like an adult whether you want it to or not.

Waves smashed over the boat deck and carried away two lifeboats. The ship took on water faster than her pumps could clear it. The stokehold’s floorplates grew slick under a rising wet breath. Through the night the list increased, and with it the anxiety of people who could read a level horizon with their inner ear. Puppe would later recall stumbling through sloshing galleys, begging for food for his wife and baby, being told to fetch it himself as the kitchen pitched and the water slapped his shoes. The hierarchy of polite service collapses quickly when the deck turns against you.

Captain William J. Carey had the radio. He also had a company’s reputation in his pocket and a flawed sense of timing. The distress call that should have gone out while the ship still had strength in her bones was delayed until 9:56 a.m. Monday. When it finally went, the position it gave was wrong by thirty-seven miles. The sea is a big place. A miss like that can be a life. The SOS was repeated at 11:04. By then Vestris was badly heeled to starboard, almost on her beam ends, the kind of posture that turns every corridor into a wall. The order to abandon ship followed between 11 and noon, an order that would have meant order if it had been prepared for. It had not been. The ship’s architecture and her angle dictated that only port boats could be launched. They hung fifty to sixty feet up, in dirty weather, tended by men who looked as though they had never lowered a boat in earnest in their lives.

There are times when a ship becomes a classroom. The lesson that day was chaos. Passengers saw crew running from boat to boat, shifting gear and provisions not to the boats where women and children sat, but to the boats where their friends waited. They watched lifeboats slam, stove, fall, or flood. One davit broke loose and crushed the boat below. Another boat was hauled down with the ship because no one cleared the falls in time. The old social code that promised “women and children first” was honored, and then negated, by incompetence. When Vestris slid under at two in the afternoon, she took with her every child aboard. Of the thirty-plus women, only a handful survived. The phrase that passed from newsroom to inquiry was acid and accurate. Women and children first, to drown.

The captain went down with his ship. Witnesses saw him walking along the port side without a lifebelt, speaking to the air. “My God. My God. I am not to blame for this.” If those were his words, they are the saddest epitaph imaginable. Responsibility is not a feeling. It is a set of actions taken when they are hard to take. At about 2 p.m., roughly two hundred miles off the Virginia Capes, over water more than a mile deep, Vestris rolled and sank. Rescue ships reached the scene hours later. The American Shipper, the Myriam, the Berlin, and the battleship USS Wyoming picked survivors out of the sea and brought bodies aboard, the slow arithmetic of an afternoon that should never have happened.

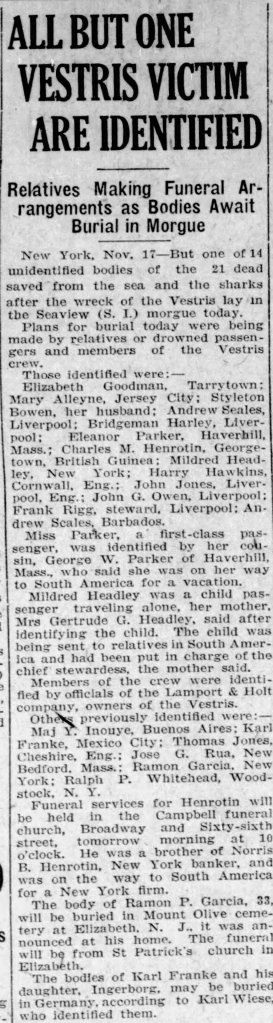

When the counting finally stopped, the press agreed on numbers that still make the jaw clench. Of 128 passengers and 198 crew, 111 people were dead or missing. Sixty-eight of the dead were passengers. Forty-three were crew. None of the thirteen children lived. Ten women at most survived. Twenty-two bodies were recovered. Names in the columns included two Indianapolis 500 drivers, Norman Batten and Earl Devore, and the father of major league pitcher Sam Nahem, proof yet again that fame has no bargaining power with the sea.

The public mood hardened. Even by the standards of the Roaring Twenties, with their fast talk and faster denials, the excuses sounded cheap. In New York and London the inquiries opened, and under oath the varnish came off. Frank William Johnson, the senior surviving officer, told the Board of Trade that the ship was overloaded and that Captain Carey had told him to be careful what he put in the log about the draft, a careful phrase Johnson understood to mean a false entry. There had been an effort, he said, to bury the overloading in silence. “We did not want the American people to get hold of this overloading business.” That sentence alone could have powered the outrage for a year. He had said none of this in the earlier U.S. hearing, where he blamed weather and admitted ignorance of duties he ought to have known. Under the second set of lights the story changed. The truth tends to leak the way water does, slow at first, then in a rush.

The Puppe testimony, and accounts like it, gave the disaster a human frame the public could not ignore. A steward too drunk to work. A galley sloshing like a sink. A father wading through a tilted corridor with bananas for a sick infant while the men in charge argued with gravity. It was a portrait of a ship with a crew that had been treated like longshoremen one minute and magicians the next. You cannot conjure seamanship. It is learned, drilled, and demanded. Vestris did not have enough of it when it counted.

Amid the collapse of professionalism, one name survived because his work saved lives the way a lifeline does, by holding. Lionel Licorish, a twenty-three-year-old quartermaster from Barbados, unlashed an extra boat and kept it afloat through fourteen hours of pounding water. Survivors credited him with rescuing between sixteen and twenty people. “The only member of the crew who exerted himself on our behalf,” one said. Charles Tuttle, the federal attorney, called him “a hero of the sea.” New York’s mayor honored him. He toured briefly as a symbol of courage. Then the tide of attention went out. In a country where Black sailors were generally locked into the lowest billets and kept away from advancement, Licorish’s moment was presented as an exception to a racist rule rather than a rebuke of it. He returned to the Caribbean, ran afoul of a smuggling charge, and was later killed in the Merchant Navy during the Second World War. The sea gives and the sea takes, but society decides who gets written into the syllabus. Licorish belongs there. His competence and nerve are the counter-argument to the lazy scapegoating that tried to pin the Vestris on nameless Black crewmen rather than on the decisions of officers and owners.

The legal reckoning was ugly, then quiet. Lamport and Holt faced a blizzard of lawsuits, hundreds of claimants totaling millions of dollars. The company settled for a lump sum of about one hundred thousand pounds, a figure that moved the suits off the docket and, conveniently, kept some testimony out of open court. The real penalty was commercial. Bookings cratered. The company pulled out of the New York trade and shut its South American passenger service by the end of 1929. The market is moral only by accident, but sometimes the accident is enough.

Reform came, as it so often does, from the corpses. Rescuers found bodies face down in cork lifejackets that were supposed to be salvation. Those vests could keep you afloat, but not necessarily keep your mouth and nose out of the water if you were unconscious. A U.S. Navy officer pressed for kapok lifejackets that would cradle the face higher. The outcry helped push the first widely accepted International Convention for the Safety of Life at Sea in 1929, the SOLAS code whose lineage runs through every passenger ship afloat today. The lessons were not all about foam and cork. Radio discipline, distress procedures, lifeboat drill standards, and better gear for launching boats from listing ships in rough water all got attention in the years that followed. If you are the sort who thinks regulations are simply a bureaucrat’s way of spoiling a good time, read the casualty counts and then decide. The paperwork was written to stop scenes like Vestris’s port boat falling onto the heads of the people who needed it most.

Step back and the pattern sharpens. The weather was real. The gale existed. But storms are tests, not causes. What sank Vestris was a chain of human choices and organizational habits. Leave a coal port a little ajar because it is usually fine. Ignore the list because it is probably cargo. Delay the SOS because the company would prefer you did. Fail to train crews thoroughly because drill takes time and time is money. Then act surprised when gravity and water do what gravity and water always do. Modern analysts of survival at sea point out that a great many deaths in cold water occur not from dramatic hypothermia but in the first minutes through cold shock and swimming failure. Equipment has to be designed for people under stress with limited cognitive bandwidth. Culture has to assume that in real emergencies, humans will be at their least perfect and so systems must help them succeed anyway. Replace the word “equipment” with “lifeboat tackle” and the word “systems” with “company practice” and you have the Vestris in a nutshell.

You can measure her legacy by subtraction. Since 1929, better vests have kept more heads out of the water. Better drills have put more people into boats without killing them on the way down. Better radios have drawn rescue ships to the right patch of sea, not to the coordinates of a wish. None of that is a triumph to celebrate. It is the bare minimum that decency requires. But it matters. It means that some child who would have been a statistic in 1928 is a grandmother telling a story today.

There is also a smaller, sharper legacy. Vestris became a cultural shorthand in the late 1920s. A sneer. A byline. Lorena Hickok, who covered the disaster for the Associated Press, saw her story run in The New York Times under a woman’s byline, a first for that paper. That footnote has a human face. Reporters hammered the company, the crew, and the Board of Trade with equal vigor. Public confidence in the ocean liners, never rock solid after the Titanic and Empress of Ireland, tilted again. This time the villain was not ice or another ship. It was the ordinary sin of pretending everything is fine. In that sense, Vestris reads like a parable for more than ships.

For the historian, the hardest part is the small hour. Imagine the Monday morning on a steeply canted deck. The clock somewhere near ten. The stewardess who has done everything for other people for twenty years now sitting in a boat that will never touch the sea. The father who believes, with the simplicity of a decent man, that of course someone sent the SOS last night. The captain walking with an old world idea of honor that had been emptied of its content by the delay that killed his passengers. The quartermaster who keeps his hands moving because skill and courage are the only noble currencies that still spend in weather like this. The smell of hot metal and cold salt. The sound of crockery sliding in a dark pantry. The moment when the angle changes from bad to final, and everyone knows it, and no one can help. Write the rules later if you must, but write this down too. Respect for the sea is not enough. You must have respect for the people who trust you to meet it.

If you are tempted to shrug off the load line numbers and the battened hatches as trivia, consider how often institutions fail in exactly this way. Not by flamboyant scandal, but by a hundred little surrenders to convenience. The coal port that is close to shut. The ballast you will pump tomorrow. The drill you will hold next week. Then the gale makes a simple request. Prove you have done your work. Vestris could not do so, and the price landed on mothers and children first.

There is a right way to close a story like this. Not with a sermon, but with a simple accounting. Vestris left New York too deep and ill prepared. She met a common storm and did not behave as a ship should. Her captain delayed the call for help and then could not manage an orderly abandonment. Her crew included brave professionals and untrained opportunists. Her owners paid out and pulled back from the trade rather than stand in the dock of public opinion any longer. Her dead taught the living to fix their gear and their habits. Her hero’s name was Lionel Licorish. Remember him. He is proof that, on the day, the person who saves you may not be the one with the title. He is proof that competence under pressure is the only rank that matters.

And the wreck. It lies about a mile down, somewhere beneath the latitude and longitude that the captain did not send. No one goes there. The sea holds its archives close. But every time a passenger ship runs lifeboat drill with seriousness, every time a purser checks a door twice, every time a captain calls distress early rather than late, a page turns in that cold library. It says we learned something. It says the arithmetic can change.

Specifications and service history place Vestris among the mid-sized liners of her day, the honest workhorses that kept migrants and merchants moving. She was never a record breaker. She was never meant to be. She was meant to leave and arrive. That is the whole point of a passenger ship. The December that followed her loss saw angry editorials, sorrow, and a clammy sense of familiarity. We had been here before. We would be here again. But the law took notice, and the industry adjusted, and the next generation went to sea with better odds. That does not console the Pupes or the dozens of families whose names never made headlines. It does honor them, a little, to say this clearly. The reason we have the rules we have is because of days like November 12, 1928.

If you want the clean doctrine, you can find it in the hearing reports. Overloading. Improper stowage. Failure to pump ballast. Coal bunker hatches unbattened. A partially open coal port near the waterline. Progressive flooding. A delayed and inaccurate distress call. A poor abandonment sequence under severe heel. Lifeboats lost at the falls. Fatalities concentrated among women and children. Heroism isolated and unofficial. Company settlements. Service withdrawn. SOLAS strengthened. Lifejackets improved. Drills standardized. Radios disciplined. You could print that on a checklist and pin it to a bulkhead. But you should also remember what the list cost to compile.

The skeptic in me will always ask whether we forget as fast as we learn. Regulations drift. Training dulls. Budgets squeeze. The sea waits. That is why stories like Vestris matter. They are not ghosts rattling teacups. They are alarms that never quite stop ringing. Keep the hatches dogged. Keep the ballast where it belongs. Drill until the hands move without thinking. Send the call early. Put the right people in charge. Treat courage as a job description, not a miracle. And for the love of all the families who bought a ticket believing in a safe arrival, never, ever, gamble that reputation can beat physics. It cannot. It never will.

Vestris is not a legend. She is a ledger. On one side, a handsome ship, a steady route, a company brochure that sold sunshine and reliability. On the other, a coal port left open, a captain who waited, lifeboats that killed the people they were meant to save, and a boy from Barbados who did not wait for orders to do the work that had to be done. Balance the books. Then vow to keep them balanced. The ocean will check your math.

The numbers and events are not quarrelsome. They are plain. Vestris left with 128 passengers and 198 crew. She met heavy weather about two hundred miles off the Virginia Capes. She sent her first SOS at 9:56 a.m. on November 12 with an error of roughly thirty-seven miles. She repeated the call at 11:04. She ordered abandonment between 11 and noon. She heeled and sank at about 2 p.m. Rescue ships arrived in the evening. Of those aboard, 111 died or were missing. Every child was lost. The captain died with his ship. Inquiries blamed overloading, poor stowage, delayed distress, and bungled boat handling. The company settled claims and withdrew service. SOLAS was strengthened. Lifejackets were improved. That is the spine of the story. The rest is flesh. The rest is us.

If you have read this far, you already understand the moral. The sea is not sentimental. It rewards preparation and punishes vanity. The SS Vestris did not fail because the Atlantic is cruel. She failed because men were careless and slow. Fixing that is the point of history. Not to scold the dead, but to guard the living. If a single reader tightens a procedure or sends a message sooner because of this ship, then the last chapter is not only tragedy. It is service.

Sources, figures, and quotations in this account are drawn from the technical and narrative records preserved in the contemporary inquiries and later syntheses. Vestris’s specifications, final voyage timeline, casualty figures, route, and inquiry findings appear in the compiled history and proceedings, including the London and New York records and a consolidated historical summary that details her tonnage, dimensions, engines, service history, and the sequence of events from the gale through the SOS messages, abandonment, and rescue operations. Eyewitness testimony about the drunk steward, the worsening list, the mishandled boats, the delay in distress, and the human cost appears in period reports and a curated narrative that reproduces hearing-room exchanges and survivor statements, including those of Fred W. Puppe. The Board of Trade and U.S. inquiry material includes Frank William Johnson’s admission about overloading and the captain’s direction regarding the draft log entry, which speaks to a deliberate effort to keep the truth out of American newspapers while lives still hung in the balance. The broader safety legacy, including lifejacket reform and the 1929 SOLAS convention, is traced in maritime retrospectives linking the face-down recoveries in cork vests to the push for kapok designs and stronger international standards, a line of cause and effect as cold as the water itself. And the memory of Lionel Licorish comes through not as an anecdote but as a matter of record, with named officials and honored ceremonies corroborating what survivors had already said on the deck of a heaving boat. He stood up when it mattered. That is the heart of it, then and now.

Leave a comment