The night was hot and damp, the kind of Ironbottom Sound night where radar screens glow like fireflies and men squint into darkness until their eyes ache. On the chart, Cape Esperance sat like a knuckle on the northwest corner of Guadalcanal. To the east lay Savo Island with its recent ghosts. The last time Allied cruisers were caught here the water filled with oil and bodies and that awful feeling settled into the fleet, the sense that the Japanese owned the night. On October 11, 1942, an American task force returned to that same patch of ocean to argue with the darkness. Out there, in the broken weather and scattered squalls, Norman Scott set his ships in line and went looking for trouble.

The battle that followed would be remembered by two names, the Battle of Cape Esperance, and the Second Battle of Savo Island. It unfolded between the late hours of October 11 and the early minutes of October 12. It ended with American guns hammering Japanese cruisers at close range, a heavy cruiser and a destroyer gone to the bottom, and the U.S. Navy claiming a clean victory. It was a victory, and it mattered. It was also messier than the headlines. The night gave, and it took, and as always around Guadalcanal, the island and the Slot swallowed neat conclusions.

By October 1942, the United States had been at war for nearly a year and was still fighting with its back to a door that refused to close. The Marines who had seized the unfinished airfield on Guadalcanal in August were hanging on by grit and prayer. Henderson Field gave daylight its teeth. After dark, the Japanese turned the Slot into a conveyor belt. They called those high speed runs the Tokyo Express. Light cruisers and destroyers whipped down from the Shortlands, dumped men and supplies, and vanished before the sun could punish them. Heavy cargo moved by slow transport died in daylight. So the Japanese sent flesh and rifle rounds by night and bet that would be enough to push the Marines into the sea.

Japan’s 17th Army was preparing another try at the island. The next big shove aimed for late October, with fresh infantry and heavy guns to smash Henderson Field from the land side. The Americans knew they needed more men on the island and they needed them fast. Major General Millard Harmon leaned on Vice Admiral Robert Ghormley to get reinforcements moving. The U.S. Army’s 164th Infantry Regiment, 2,837 men, sailed from New Caledonia on October 8 with an arrival target of October 13. The convoy could not be left to the mercy of the night. To guard it, and to claw back some control after the Savo debacle, Rear Admiral Norman Scott took Task Force 64 to sea with plain orders. Screen the transports. Patrol the approaches. Search for and destroy the enemy.

Scott was not a theorist. He was a sober destroyer man who had read the Savo Island report like Scripture, pen in hand. He drove his crews through dusk to dawn general quarters and night gunnery until nerves frayed. He believed in discipline. He believed that a tight formation was safety and that control would win a knife fight. He did not, however, put his flag in the most advanced piece of electronics he owned. The light cruisers Boise and Helena carried the new SG radar. San Francisco, Scott’s chosen flagship, did not. He preferred to sit in a ship he knew and trust optics and voice commands over an instrument he still thought finicky. It was an old sailor’s choice. It would color everything that followed.

Task Force 64 was a small battering ram. Heavy cruisers San Francisco and Salt Lake City carried eight inch rifles and scars from earlier fights. Light cruisers Boise and Helena came bristling with fifteen six inch guns each. Five destroyers flanked them. Farenholt, Duncan, Laffey, Buchanan, and McCalla, slim and fast, with torpedoes that could end arguments if given a clean shot. The destroyer squadron commander, Captain R. G. Tobin, rode Farenholt. They were not a perfect team yet, but they were mean enough and practiced enough to try the night again.

(PUBLIC DOMAIN)

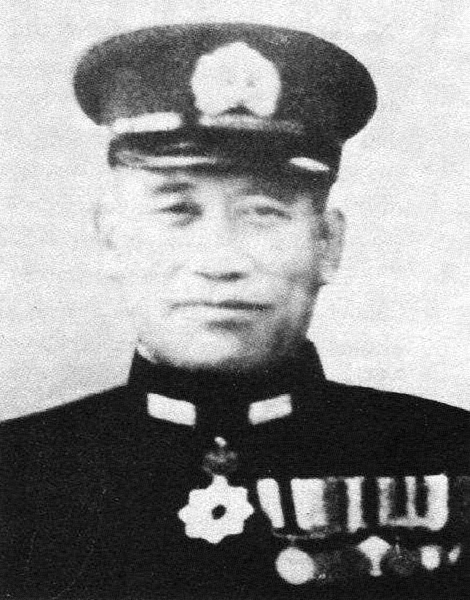

The Japanese came in two pieces. Rear Admiral Aritomo Gotō’s Bombardment Group brought Aoba, Furutaka, and Kinugasa, all veterans of Savo, plus the destroyers Fubuki and Hatsuyuki. Their magazines were packed for a shore job, high explosive for Henderson Field rather than armor piercing for ship duels. Behind them, Rear Admiral Takatsugu Jōjima shepherded the reinforcement echelon. Seaplane tenders Nisshin and Chitose hauled men and heavy equipment, including large howitzers the Japanese believed would settle Henderson Field once and for all. Six destroyers screened the transports, among them Asagumo, Natsugumo, Yamagumo, Shirayuki, Murakumo, and the new Akizuki. They intended to land, bombard, and slip away as they had done so many times.

The day gave the Americans a gift. At mid afternoon on October 11, U.S. aircraft sighted the reinforcement convoy. Scott turned to intercept and by late evening his line had passed Cape Esperance and settled into column. Destroyers led, then Helena and Boise, then the two heavy cruisers, with more destroyers in trail. The sea breathed in the dark. U.S. floatplanes clawed into the night to patrol. Rain squalls slipped in and out like curtains. At 22:20, Jōjima radioed that the approach was clear. Gotō believed him and pressed on. At 23:30, Helena’s SG swept ghosts into shape. Contacts. A column. Closing. The Japanese had no radar. They were coming blind into a trap.

Then the human factor took a bite. At 23:33 Scott ordered a column turn to 230 degrees. He intended the classic follow the leader swing. San Francisco instead turned immediately, as if the order were a simultaneous change. Boise followed her flagship. The three leading destroyers suddenly found themselves out of position to the north, sliding into harm’s way without friends behind them. It was a stumble at the start of a sprint, and it left Scott believing that some of the blips on his screens might be those wandering destroyers. He held fire. Helena asked permission to open. She used the proper preface, Interrogatory Roger. Scott responded with a plain Roger. On Helena’s bridge that read like a green light. At 23:46 Helena’s forward turrets spoke first. Boise, Salt Lake City, and San Francisco joined, their shots climbing in arcs that felt almost cheerful after a summer of humiliation.

The surprise was absolute. Gotō’s column had just emerged from rain when red and white sparked the horizon. Aoba took the first blows. Shells chewed up her forward turrets, wrecked communications, and cut down Gotō on his bridge. He would die of his wounds while his ships tried to live. Aoba threw smoke and turned out. Americans mistook the black wall for a funeral shroud and thought they had finished her. They had not. They had hurt her badly, and that counted.

Up front, the orphaned destroyer Duncan decided there was no time to sort doctrine. She charged. Her captain believed the attack was starting. He slid in on the Japanese line, firing as he went, loosed torpedoes, and kept going until gunfire from friend and foe riddled the ship. Later analysis gave Duncan credit for savaging a cruiser as she lunged. Either way, the attack was the kind of hot blood move sailors remember with a catch in the throat. It did not save Duncan. It did help break the enemy’s shape.

Fire shifted to Furutaka. Gun flashes stabbed the rain. In the melee, Buchanan’s torpedo found the heavy cruiser forward, ripping into machinery and starting big fires. The destroyer Fubuki wandered into a storm of American shells at almost knife range and rolled under within minutes. Somewhere in the cross talk Scott ordered a ceasefire to sort targets. Not everyone heard. Farenholt, trying to regain station, took hits from both sides. Duncan burned, lost power, and began to die slowly. The night, victorious or not, was already writing casualty lists.

Kinugasa fought as she fled. Around ten minutes past midnight two eight inch rounds from her guns slammed into Boise. One burst in the forward magazine complex, killing nearly one hundred men in an instant and blowing fire up through the forward turrets. Another struck low, possibly a waterline runner designed to dive under armor and erupt inside. For a few long minutes, Boise hung on the edge of catastrophe. Flooding that should have been a curse helped the crew. Powder fires choked, magazines stayed just wet enough, and the ship did not become a star in the black sky. Hull and heart damaged, Boise sheered out, still firing her after turrets as she fell away. By the end of it she had burned through more than eight hundred rounds and much of her luck.

With Aoba battered, Furutaka flaming, Fubuki gone, and Kinugasa playing matador to draw attention and live, the Japanese broke contact. Hatsuyuki slipped clear. Scott tried to reform in the smoke and squalls and chase, but visibility and scattered stations made a clean pursuit a gamble. By twenty past midnight the shooting had run down to nervous bursts and isolated flashes. Scott turned his ships south to reset and keep faith with the transports. Behind the American stern lights, Furutaka’s fight to survive ended in a slow settle. She lost power and went down after two in the morning northwest of Savo. It was the first time a Japanese heavy cruiser had been gunned under by enemy surface ships in this war. It felt like a weight coming off the chest.

Dawn found the butcher’s bill still climbing. Duncan’s crew abandoned their wreck around two in the morning. McCalla risked sharks and the predictable terrors of that water to pull 195 men from the sea. Duncan finally slipped under near noon on the twelfth, six miles north of Savo. Farenholt carried scars from both enemies and friends and counted three dead. Boise’s dead numbered 107, most of them trapped or cut down near the forward magazines. Yet the crew had done what crews dream of doing. They had kept their ship alive. By three in the morning she was back in formation. Her next stops would be Espiritu Santo and then the long run to Philadelphia for surgery, a grim parade of twisted steel and fire burned paint that America turned into a rally poster. The total American dead reached 163, with 125 wounded.

The Japanese losses were worse on paper and uglier in the details. Furutaka and Fubuki were gone. Aoba limped home with a murdered bridge and a broken face. Vice Admiral Gotō would not see the repairs. Casualty counts vary, as they always do after night and water, but more than three hundred died and more than one hundred were captured, many of them Fubuki survivors who at first pushed rescuers away rather than trade waves for a prison hold. The next day added insult. Jōjima’s reinforcement group had actually completed its unloading under the Americans’ noses. While Scott was feeling out the darkness, Nisshin and Chitose got their men and heavy equipment ashore and then headed north. When Japanese destroyers pulled back to pick up stragglers and shield the damaged bombardment force, aircraft from Henderson Field fell on them. Murakumo took a torpedo and lay dead in the water until Shirayuki scuttled her. Natsugumo took bombs and sank by late afternoon. It was a delayed payment rather than a refund for the previous night.

So who won?

Tactically, the Americans did. The gunnery was punishing once it began. A veteran heavy cruiser and a first class destroyer were gone. A third cruiser was out of action for months. The U.S. Navy proved to itself that it could strike first in the night and that its crews could keep fighting when the plan broke in their hands. That mattered to morale. It mattered to the way men walked up gangplanks the next week. The myth of untouchable Japanese night fighting cracked. Newspapers shouted. Boise came home to fanfare and the nickname that sets a historian’s teeth on edge, the one ship fleet. Scott told higher command he had sunk three cruisers and four destroyers. Boise’s bridge scoreboard sprouted little silhouettes like a hunter’s wall. On the other side, the Japanese reported two American cruisers and a destroyer sunk. Overclaiming was a disease that infected both navies in the Solomons. It fed parades. It also fed mistakes.

Strategically, the night was not decisive. The convoy landed what it needed to land. Japanese infantry and heavy guns were in the jungle, marching for the airfield and digging their way into the ridges and river lines that would soon fill with bodies. Two nights later, the battleships Kongō and Haruna came down the Slot and poured nearly a thousand fourteen inch shells into Henderson Field. The damage was savage. Runways cratered, revetments burned, crews lay flat and clenched their teeth while steel shrieked overhead. Daylight aviation survived, which says something about the stubborn life that grew on that airstrip, but the message was clear. One good night action did not tame the Slot by itself. What Scott’s cruisers did do was hold the door open long enough. The 164th Infantry arrived on schedule and within two weeks those soldiers would help stop the big October ground offensive that tried to bulldoze Henderson Field off the map. In that sense, Cape Esperance did exactly what it needed to do. It bought time and it bought confidence, and the island used both.

There is a temptation, when telling a battle like this, to write it as an easy turning point. That is not honest. The Americans learned the wrong lessons along with the right ones. A victory that arrives despite confusion can breed the habit of shrugging off confusion. Scott’s formation was too congested for the destroyers to make coordinated torpedo runs. Recognition lights and challenge signals flickered far too freely, a fatal quirk that would haunt later nights. Fire discipline wavered, which is how Farenholt ended up with American shells in her plating and how Duncan’s last minutes turned into a cross fire. Communications between radar equipped cruisers and a radar blind flagship lagged. Those habits did not vanish with a good headline. A month later in a brutal November midnight fight off Guadalcanal, Norman Scott was killed in Atlanta when friendly eight inch shells from San Francisco tore through the light cruiser. The darkness never stopped billing.

Memories from the men who were there catch the real taste. One junior officer from Helena later called it a three sided battle where chance was the major winner. It is a sharp line, and it respects the truth. Scott’s drills and Helena’s radar and Boise’s gunners mattered. So did a rain squall. So did a misread turn. So did a flawed shell that dove and exploded inside a magazine where floodwater had gathered just enough to choke the fire. You can prepare to the limit and still need luck, and then you have to be good enough to spend the luck before it evaporates.

By the time the yards in Philadelphia had finished picking Boise apart and putting her back together, the campaign had rolled past this particular night and into a string of others that chewed up cruisers like driftwood. Kinugasa, the heavy cruiser that bloodied Boise, did not live to see Christmas. American dive bombers and the daytime phase of the November naval battle found her and sent her down. Aoba returned to service and fought again because ships in this war rarely retired cleanly. The names came back in dispatches and casualty telegrams until the Solomons campaign burned itself out and left a map covered in pencil lines and little crosses.

If you look out from Cape Esperance today and let your eyes soften, you can almost see the column, just a dotted lantern trail along the swell. You can hear the ripple of fifteen six inch guns cycling together and the thud of eight inch shells finding something they were not meant to find. You can hear a destroyer captain say to no one in particular that this is as good a time as any and then push the throttles forward. The battle did not end the reinforcement runs. It did not keep the battleships away two nights later. It did send a message across the fleet that the night did not belong to one side. That belief, crazy or not, kept men at their stations when the next wave came.

The tally was grim but telling. The United States lost two destroyers, Duncan and Farenholt, along with 163 sailors killed and 125 wounded. Boise took what looked like a mortal hit to her forward magazines but refused to die, her crew’s quick action saving both ship and survivors. Farenholt limped away, scarred by both friendly and enemy fire. Japan lost more in ships and men, with a heavy cruiser and a destroyer sunk during the night and two more destroyers destroyed by American aircraft the next day. Hundreds of Japanese sailors were killed or captured. Even so, Jōjima’s transport group landed its men and heavy equipment on Guadalcanal, while Scott’s convoy arrived on schedule to reinforce the Marines. The 164th Infantry dug in and later helped hold the line at Henderson Field. The fleet’s morale rose, the Tokyo Express kept running, and both sides claimed victory. In a way, they were both right.

That is Cape Esperance. A clean win wrapped around a crooked night. A blow that shook the myth of invincibility without ending the problem it struck. A moment when the U.S. Navy learned that it could fight the night and live, even if it still did not fully understand the weapons that were hunting it. The legacy belongs to the ships and to the people who fought them, and to a commander who drilled his crews hard, trusted his gut, and died in a later round of the same argument. It belongs to a light cruiser that sailed home scorched and stubborn and became, for a time, the ship the public needed. It belongs to a thousand small decisions made in rain and glare and smoke. It belongs, finally, to Guadalcanal, which consumed heroes and metal without sentiment and gave back only this lesson. If you want to hold a place like that, you hold it at night and in the rain and you do not quit when the plan comes apart.

Leave a comment