Berlin in the summer of 1948 was a city still bleeding from the wounds of the war. The bombs had fallen for years without mercy, leaving whole neighborhoods flattened into heaps of stone and dust. Children played in the ruins of buildings that no longer had roofs or walls, and families made homes in the shells of apartments that stood like skeletons against the sky. Food was scarce, coal scarcer still, and the people who had survived the fighting were now fighting something quieter and in some ways crueler: hunger, cold, and despair. The war had ended, but peace had not truly come.

The Soviet Union made certain of that. From their position surrounding the city, they cut off every road, canal, and rail line into West Berlin. They even turned out the lights, cutting electricity from plants under their control. Over two million civilians, many of them children, were left with only a few weeks’ worth of food and fuel. The message from Moscow was clear. Give up. Abandon the city. Let Berlin fall into the communist orbit.

The Western Allies faced a choice. They could back down, retreat, and concede the heart of Germany to the Soviets. Or they could resist, not with tanks and guns but with something stranger, something no one had ever attempted on such a scale before. They would keep a city alive from the sky. That plan would come to be called the Berlin Airlift, a feat of endurance, engineering, and sheer stubbornness. It would become one of the defining moments of the Cold War.

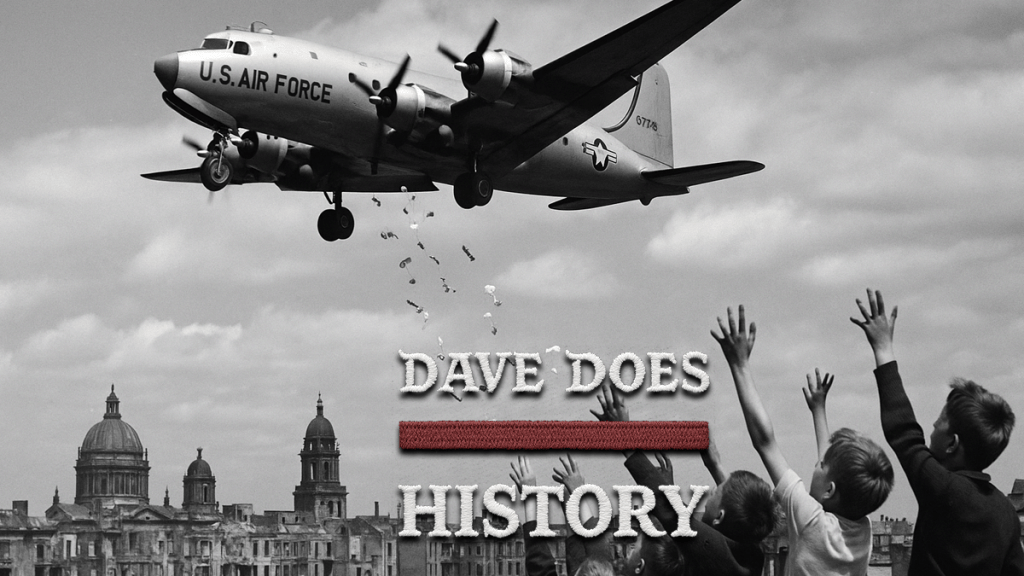

But within that grand story of coal tonnage and flight schedules, there was another tale, almost too small to notice at first. It began with a single pilot, a couple of sticks of chewing gum, and a promise made to a group of children behind a fence at Tempelhof Airport. That pilot was Gail Halvorsen, and before the airlift was over he would be known around the world as the Candy Bomber. His story reminds us that sometimes history turns not on the decisions of generals or politicians but on the smallest acts of human decency, and that kindness itself can be a weapon more powerful than guns.

The end of the Second World War did not bring clarity to Germany, only a new kind of occupation. The victors carved the country into four zones of control, with the United States, Britain, France, and the Soviet Union each taking their share. Berlin, the former capital of the Reich, was also divided the same way, even though it sat like an island a hundred miles deep inside the Soviet zone. At first the arrangement was meant to be temporary, a stopgap until a peace treaty could determine Germany’s future. But that treaty never came. What arrived instead was suspicion, resentment, and a steady tightening of lines that turned allies of necessity into bitter rivals.

The Soviets had suffered more than any other power during the war, and they were determined not to let a resurgent Germany rise again to threaten them. In their zone, they forced political parties to merge under communist control, created a centralized government, and drained resources eastward. They wanted Germany remade in their image, shackled to the Soviet system. The Western powers saw things differently. For them, Germany was the key to rebuilding Europe. The Marshall Plan was pouring aid into Western Europe, and West Germany was to be tied into that recovery, rebuilt into a stable, democratic state. That clash of visions was the heart of the Cold War, and nowhere was it sharper than in Berlin.

The spark came with money. The German Reichsmark, battered and nearly worthless, kept the economy on its knees. The Western Allies decided that stabilization required a new currency. On June 21, 1948, they introduced the Deutsche Mark in their zones and in West Berlin. Overnight, the fragile balance between East and West collapsed. To Moscow, this was not just a monetary change, it was a direct threat to their influence. If West Berlin adopted the new currency, it would anchor the city to the Western economy, pulling the rest of Germany with it. The Soviets were not about to allow that.

Three days later, on June 24, they made their move. Every road and rail line into West Berlin was shut down. Barges were stopped. Even the electricity supplied from the Soviet zone was switched off. The city went dark and the warehouses emptied. At best, the people had a little more than a month of food and coal left. Soviet propaganda taunted the West, predicting that the Americans and British would cut their losses and abandon the city. To the Soviet mind, it was a perfect gamble. The Allies had no treaty guaranteeing land access to Berlin, and no army on the continent strong enough to fight their way in. If the city starved, the West would be forced to yield, and Berlin would fall into the Soviet orbit without a single shot being fired.

The blockade was as much a test of will as it was a stranglehold on supplies. The Soviets believed that the West would never risk war over Berlin. They were sure the Americans would not spend treasure and lives to feed two million former enemies. In truth, even Washington was divided, unsure if the city could be held. The people of Berlin, already weary and thin, watched and waited to see if they were to be abandoned.

Good. Now we shift into the airlift itself, the story of Operation Vittles, about 550 words. This section needs to capture the scale, the ingenuity, the near disasters, and the way the Allies pulled off the impossible. Here’s the draft in continuous narrative, no headers.

The Western commanders knew that abandoning Berlin would be a humiliation from which they might never recover. General Lucius D. Clay, the American military governor, cabled Washington with blunt words: staying in Berlin was essential, not just for Germany but for the credibility of the United States across Europe. If they pulled out, the Soviets would not stop at Berlin. They would use the retreat to prove that America lacked the will to protect Western Europe. Yet the practical problem was staggering. How do you feed and heat two million people in a landlocked city without trains, barges, or trucks? The answer was air.

The Allies retained legal access to three narrow air corridors into Berlin. On June 26, 1948, just two days after the blockade began, the first flights left for Tempelhof. They called it Operation Vittles, and in Britain the effort went by the name Operation Plainfare. At first it looked like a desperate improvisation. The little C-47 Skytrains could carry just three and a half tons of flour or powdered milk. To keep Berlin alive, the city needed more than 4,500 tons of food and coal every single day. The first days barely scratched the surface. Pilots flew back and forth constantly, their planes so overloaded that flour dust clung to the cabin walls. The long days quickly blurred into nights as the convoys of aircraft roared through the sky, often landing only to turn around and do it all again.

It was not enough. Unless the operation could be scaled up, the city would starve. In July, the man who had once rescued the Hump operation over the Himalayas was brought in. Maj. Gen. William Tunner looked at the chaos and decided that discipline and efficiency would win the day. He banned the old practice of circling aircraft over the city waiting to land. From now on, every pilot had one chance to land. Miss it, and you flew back to base. He ordered instrument flying at all times, whether the skies were clear or fogged in. He cut out wasted minutes by forbidding aircrews to leave their planes in Berlin. Jeep-mounted snack bars met them at the runway with sandwiches and coffee. Turnaround time dropped to half an hour.

The planes changed too. The smaller C-47s gave way to the bigger C-54 Skymasters. Each carried nearly ten tons of cargo and took no longer to unload than the smaller aircraft. Runways were improved, and in a remarkable feat, German civilians built an entirely new airport at Tegel in less than three months, hauling away the wreckage of Nazi flak towers by hand and cart. Berlin itself was rebuilding even as it was being supplied.

Still, the dangers were constant. Fog closed the runways for days at a time, leaving the city’s coal piles dwindling to almost nothing. Soviet fighters buzzed Allied planes, parachutists dropped near the corridors to startle crews, and searchlights blinded pilots at night. There were crashes and fires, and a total of 101 lives lost, most from accidents that came with flying so relentlessly. Yet the stream of aircraft never stopped. By April 1949, they were delivering more by air than Berlin had ever received by rail before the blockade. In a single twenty-four hour stretch that month, they delivered 12,941 tons of coal in what became known as the Easter Parade. At the height of the operation, one plane touched down every thirty seconds. By the time it ended, the Allies had flown more than 278,000 missions and delivered 2.3 million tons of supplies.

It was a feat no one had believed possible, and it stunned the Soviets. The city was surviving. Berliners did not starve, they endured. The blockade was no longer a chokehold, it was an embarrassment to those who had tried to enforce it. Yet amid the grind of tonnage charts and flight schedules, another story began to unfold, one that revealed a different side of the airlift.

For most pilots, the Berlin Airlift was a relentless cycle of monotony. Load the sacks of flour or coal, take off, fly through the corridor, land in Berlin, unload, and do it again. The work was necessary, the mission clear, but the hours were long and the exhaustion heavy. Few of them gave much thought to the people on the ground beyond the fact that their cargo kept them alive. Gail Halvorsen, a young lieutenant from Utah, began much the same way. He was grateful for the chance to fly, committed to the mission, but he did not expect to be moved by the very people he was helping.

That changed one afternoon in July 1948. Halvorsen had been filming aircraft movements at Tempelhof Airport, his small camera capturing the endless stream of planes, when he noticed a cluster of children standing behind a barbed-wire fence. There were about thirty of them, ragged, thin, yet disciplined in the way they stood. He walked over, curious, and struck up a conversation. His German was poor, their English halting, but they managed. What surprised him was that they did not beg. These were children who had lived through the destruction of their city, who knew hunger intimately, yet they thanked him for the food flights, for the hope of freedom. One of them said simply, “If we lose our freedom, we may never get it back.” The words struck him harder than he expected. He reached into his pocket and found only two sticks of chewing gum. It was not much, but it was all he had. He passed them through the fence. The children tore them into the smallest pieces imaginable, sharing without complaint. Those who got nothing took the empty wrappers, closed their eyes, and breathed in the faint sweetness.

Halvorsen walked away shaken. That night he decided he had to do more. He told the children he would return, and they would know his plane because he would wiggle the wings as he came in to land. Then, using his candy rations and those of his crew, he tied chocolate bars and chewing gum to little parachutes fashioned from handkerchiefs. The next day he flew his run, waggled the wings, and released the packages. The sight of candy floating down on tiny parachutes transformed the grim airfield into a place of wonder. The children scrambled to collect them, laughing for the first time in a long while.

Word spread quickly. Letters arrived at the base addressed to “Uncle Wiggly Wings” and “The Chocolate Flier.” Some in the chain of command bristled. At first Halvorsen was threatened with discipline for conducting an unauthorized stunt. But when General Tunner learned of it, he recognized its power. In a battle that was as much about morale as supplies, this was a gift beyond measurement. What began as a single pilot’s impulse was transformed into Operation Little Vittles.

Support poured in. American schoolchildren sent candy by the boxful. A group of students in Chicopee, Massachusetts, set up an assembly line to tie candy bars to parachutes. Confectionery companies joined too. Hershey, Wrigley, and others shipped tons of chocolate and gum. Soon other pilots were dropping candy, and the skies over Berlin became the stage for something no one could have predicted.

The German children gave the planes a name: Rosinenbomber, the raisin bombers. They raced through the streets when they heard the engines overhead, eyes skyward, waiting for the flutter of handkerchief parachutes. For the Americans, it was a propaganda victory of the best kind, one rooted not in slogans or speeches but in generosity. For the children, it was joy and hope, proof that even in the ruins of their city, they were not forgotten.

By the end of the airlift, more than 23 tons of candy had been dropped on a quarter of a million parachutes. Gail Halvorsen, the boy from Utah who had once felt little sympathy for his former enemies, became a beloved figure across Germany. He was the Candy Bomber, the man whose wiggling wings meant that a gift was on the way. His act of kindness did not shorten the blockade or alter the tonnage delivered, but it reshaped hearts. In a city starved of everything, he gave them something rarer than food. He gave them delight.

By the spring of 1949 it was clear that the Soviet gamble had failed. The airlift was not only keeping Berlin alive, it was outpacing the pre-blockade deliveries by rail. The streets still bore the scars of war and the winter fog had nearly frozen the city, but the lights were on and the bread was baked each morning. The Soviets had harassed and taunted, but they had not broken the will of Berlin or the resolve of the Allies. On May 12, just after midnight, the blockade was lifted. Roads and rail lines reopened, barges moved again, and the city exhaled a weary sigh of relief. The flights did not stop immediately. Supplies continued into September to build a cushion of reserves, but the point had been made. The West had held Berlin without firing a shot.

The political consequences rippled far beyond the city. The airlift was a propaganda triumph that hardened the division of Europe. It made clear that the United States and Britain would not yield to Soviet pressure. West Berlin became a symbol of freedom in the heart of communist territory. Within months NATO was formed, and in 1955 West Germany joined the alliance. The lines of the Cold War were drawn more firmly than ever.

For the people of Berlin, though, what they remembered most were not the treaties or speeches but the steady thrum of engines overhead, the sight of parachutes drifting down, the promise that they would not be abandoned. And in that memory stood Gail Halvorsen, the Candy Bomber, who gave them more than calories or sugar. He gave them proof of compassion.

Halvorsen’s life carried that legacy forward. He rose to the rank of colonel before retiring in 1974, but his service never truly ended. He organized candy drops in Bosnia, Kosovo, even Iraq, always returning to the simple idea that small acts of kindness could change lives. He was honored in both the United States and Germany, receiving the Congressional Gold Medal and the Grand Cross of the Order of Merit. In 2024 an air traffic control tower in Wiesbaden was named for him, a fitting tribute to the man whose wings once wiggled over Berlin.

The Berlin Airlift remains one of the great feats of the twentieth century, a moment when resolve and ingenuity kept a city alive against impossible odds. For fifteen months planes traced their paths through the air corridors, bringing bread, milk, coal, and medicine. The numbers still astonish, millions of tons carried on hundreds of thousands of flights, a logistical miracle that proved the West would not yield. Yet beyond the charts and statistics, the airlift endures because of something smaller. It endures because of a young pilot who met a group of children behind a fence and chose kindness.

Gail Halvorsen showed that sometimes history turns on simple acts. Two sticks of gum, torn into tiny pieces, passed through a fence to children who asked for nothing. A promise made to wiggle the wings of his plane. Little parachutes floating down over ruined streets. These are the images that carried as much weight as any ton of coal. The Candy Bomber reminded the world that humanity is not measured only in victories or treaties but in generosity, in compassion, in the recognition of dignity even in former enemies. His story remains a lesson that the smallest gestures can change the course of memory, and that hope, like candy drifting from the sky, can be shared.

Leave a comment