The war was supposed to be over. August 1946 was meant to be a summer of recovery, not another season of graves. But peace is rarely clean, and the world that emerged after World War II was fragile, fractured, and full of sharp edges. In one of those forgotten yet telling moments, five American airmen were killed when their unarmed transport plane was shot down over Yugoslavia. Their deaths signaled that even as the guns of Hitler’s war fell silent, new conflicts were already beginning.

Europe in 1946 was a continent still in ruins. Cities like Berlin, Warsaw, and Vienna were rubble piles, their people living among the ghosts of bombed-out blocks. American GIs had returned home, hailed as victors and ready to get on with their lives. But not everyone had left. Thousands of American military personnel remained in Europe to administer occupied Germany and Austria, to oversee food shipments, and to keep order in places where order had been shattered.

Flights between Allied-controlled Vienna and Udine, Italy, were routine supply runs. C-47 transports, the workhorses of the war, carried everything from mail to spare parts. It was dull, monotonous duty, the kind that rarely makes it into the history books. Yet in the summer of 1946, even a simple supply run carried risk. The lines between Allied zones were confusing, the maps often outdated, and air corridors ill-defined. The wrong turn could take an unarmed transport into hostile skies.

And “hostile” was no exaggeration. Marshal Josip Broz Tito, the Communist partisan who had fought the Nazis with remarkable effectiveness, now ruled Yugoslavia with iron resolve. He had broken with the exiled royal government and was busy consolidating his power. To Tito, American planes skirting Yugoslav territory were intrusions to be challenged, not inconveniences to be tolerated. His pilots had orders to enforce sovereignty in a way that left no doubt who controlled the skies.

On August 9, 1946, an American C-47, flying from Vienna to Udine, drifted off course. Yugoslav fighters intercepted it. Accounts differ as to how the chase unfolded, but what is clear is that the American crew suddenly found themselves under fire. With no guns to defend themselves, they fought only for survival. The transport managed to crash-land. Miraculously, the men survived and were quickly taken prisoner by Yugoslav authorities.

Diplomatic cables flew between Belgrade and Washington. The U.S. lodged sharp protests. Yugoslavia insisted the plane had violated its airspace. The Americans were eventually released. No one died, and the State Department treated it as an ugly but manageable incident. It was filed away as one more example of the tension that seemed to be brewing in every corner of postwar Europe.

But that was only the beginning.

Just ten days later, another C-47 took the same route from Vienna to Udine. The plane’s crew had every reason to think the first incident was behind them. They were not carrying weapons. They were flying what should have been a peaceful supply mission.

Yugoslav Yak fighters appeared again. This time there was no mercy. The fighters opened fire, riddling the transport with bullets. Flames engulfed the aircraft as it plunged into the forests near the Austrian-Yugoslav border. There were no survivors. All five Americans on board were killed.

Their names were Harold Schreiber, Glen Freestone, Richard Claeys, Matthew Comko, and Chester L. Lower. They were not combatants, just airmen performing a dull but necessary task. Yet they became, unwillingly, the first American servicemen killed by hostile action in Europe after World War II.

The crash was horrific. Time magazine later described the wreckage in blunt terms, noting “blobs of flesh” on the surrounding trees. That unflinching description reflected the reality of air combat’s aftermath. There was nothing noble in the twisted metal and burned remains, only the brutality of sudden death.

For Washington, the incident could not be brushed aside. This was no accident. This was a deliberate act of aggression. Within days, the United States had issued an ultimatum demanding answers.

On August 22, 1946, the U.S. government delivered a formal protest to Yugoslavia. The note was stern. Washington demanded an immediate explanation, guarantees that American planes would not be fired upon again, and compensation for the lives lost. For a nation just months removed from fighting the Nazis, it was remarkable that the first postwar ultimatum came not against Germany but against a supposed ally from the resistance.

Yugoslavia’s response was cagey. Tito’s government expressed regret, offered condolences, and eventually agreed to pay compensation to the families of the dead. Each family would receive thirty thousand dollars, routed through the State Department. But Yugoslavia never admitted wrongdoing. Instead, it portrayed the incident as the consequence of repeated airspace violations. In their view, the Americans had brought it upon themselves.

This diplomatic dodge was characteristic of the emerging Cold War. Blame was shifted, responsibility deflected, and gestures of regret were carefully calculated to avoid any suggestion of weakness.

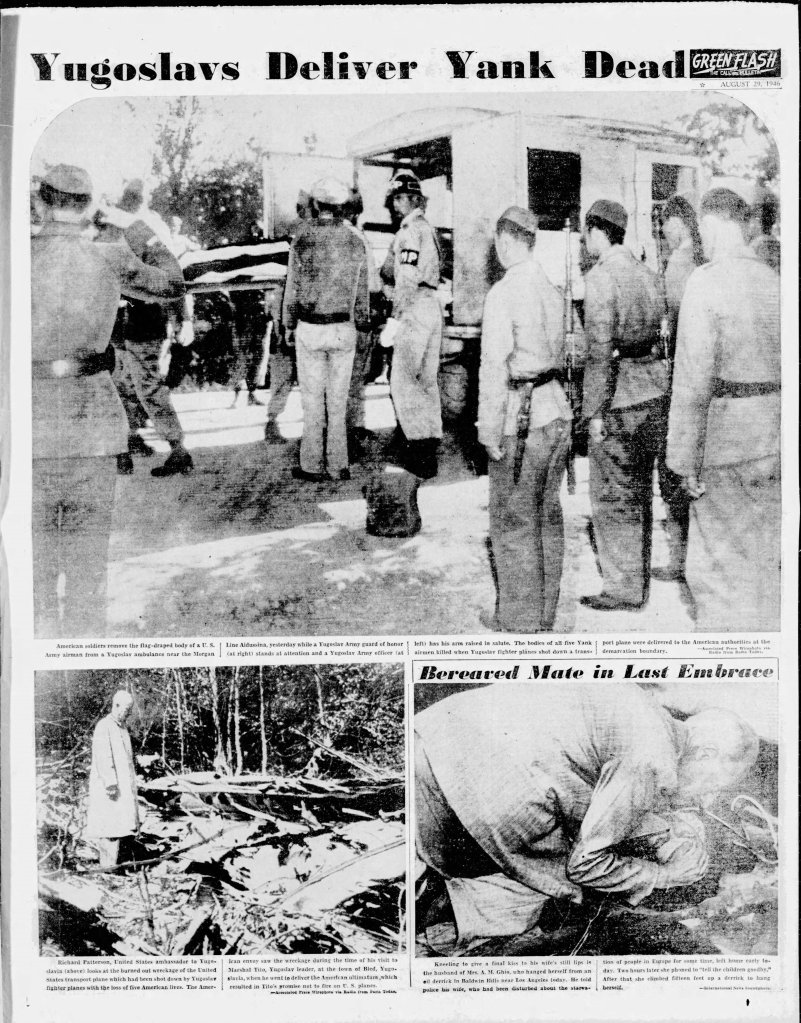

For the families of the five Americans, none of the diplomatic back-and-forth mattered. What mattered was bringing their loved ones home. On August 28, 1946, the bodies were finally returned to U.S. custody.

The San Francisco Call-Bulletin recorded the moment with solemn brevity. The coffins were handed over, the grief plain on the faces of officials and comrades who received them. It was a scene repeated too many times during the war, and now, unsettlingly, it was happening again in peacetime. The paper noted the names of the dead and the fact that they were returned under the shadow of diplomacy, not battlefield triumph.

That detail matters. These were not men who died storming a beach or liberating a city. They were killed in what should have been a routine transport flight, victims of a conflict that officially did not exist.

It is tempting to see the Yugoslav shootdown as an isolated tragedy, a sad but ultimately minor episode. But in 1946, it mattered a great deal. For one, it demonstrated just how quickly wartime alliances could sour. The United States and Yugoslavia had been partners against Hitler, but now they were staring each other down across contested airspace.

It also revealed the limits of American power. Despite the outrage, Washington did not retaliate militarily. There was no bombing of Yugoslav airfields, no punitive strike. Instead, there was diplomacy, notes exchanged, and money paid. The choice reflected both restraint and pragmatism. The United States had no appetite for another war in Europe, particularly over a small Communist country that was more annoyance than existential threat.

But the message was clear: the Cold War was already here, even if no one had yet named it.

Why would Tito risk such a confrontation? The answer lies in his precarious position in 1946. Yugoslavia had suffered terribly during the war. Tito’s partisans had fought heroically, but now he faced the task of uniting a fractured, multi-ethnic nation under Communist rule. Demonstrating strength against outsiders was one way to rally support. Shooting down American planes was a dangerous gamble, but it sent a message: Yugoslavia would not be bullied, not even by the United States.

Tito was also signaling to Moscow. In 1946, he was still aligned with Stalin. Defying the Americans demonstrated loyalty to the Soviet bloc, though Tito would later famously break with Stalin and carve his own path. At the time, however, firing on U.S. planes fit neatly into the narrative of Communist defiance.

In the grand sweep of Cold War history, the Yugoslav shootdown quickly faded into the background. Within a few years, the Berlin Airlift, the Marshall Plan, NATO, and the Korean War would dominate headlines. The deaths of five Americans in a remote corner of Europe became just one more footnote in the long catalog of postwar tensions.

Yet for the families, the memory never faded. Schreiber, Freestone, Claeys, Comko, and Lower were mourned in homes across America. They had survived the Second World War only to die in a skirmish that was not called a war at all. Their return on August 28 was a reminder that even in peacetime, service carried risks.

The Yugoslav incident stands as a marker between two eras. On one side was World War II, a conflict of clear enemies and hard-fought victories. On the other side was the Cold War, a struggle fought in shadows, proxies, and incidents that never quite amounted to war but were deadly all the same.

The five Americans killed in Yugoslavia were among the first casualties of that new era. They died not in the glory of liberation but in the gray zone of geopolitics. Their deaths carried no medals, only the uneasy recognition that the world was not at peace, no matter what the headlines said.

If you flip through the Time archives or the pages of the San Francisco Call-Bulletin, the names of the dead appear briefly before vanishing again. That is the historian’s task: to recover them, to say them out loud, to remind us that these were real men with families and lives. Harold Schreiber. Glen Freestone. Richard Claeys. Matthew Comko. Chester L. Lower. They were not symbols, but people.

And their story is part of ours. They remind us that the Cold War did not begin with speeches or treaties, but with bullets and fire in the sky. They remind us that peace is fragile, that alliances shift, and that the line between war and peace is often thinner than we like to admit.

On August 28, 1946, their bodies came home. It was a quiet moment, overshadowed by other headlines, but for the families and for the nation, it was a solemn reminder that the cost of service did not end with victory in 1945.

The Yugoslav shootdown is not remembered the way Normandy or Iwo Jima is remembered. It is not taught in classrooms or carved into monuments. But it deserves to be recalled. It tells us something about the world we inherited after World War II. It tells us that the Cold War did not arrive with a declaration but crept in through incidents like this one. And it tells us that five men paid with their lives for the messy reality of geopolitics.

In the end, history is not only about the great battles or the famous speeches. It is also about the quieter tragedies, the ones that slip between the cracks. The deaths of Schreiber, Freestone, Claeys, Comko, and Lower on that August day in 1946 are one of those tragedies. They were brought home on August 28, their coffins draped in flags, their sacrifice mostly forgotten. But they were the first to fall in a new kind of conflict, and remembering them keeps alive the truth that the past is never as simple as we wish it to be.

Leave a comment