The latest episode of Dave Does History on Bill Mick Live is a reminder that sometimes the shortest words carry the deepest weight. On November 19, 1863, President Abraham Lincoln rose at Gettysburg and spoke for barely two minutes. His remarks were meant to follow a two-hour oration by Edward Everett, the celebrated speaker of the day. Everett’s address has been lost to history, but Lincoln’s 272 words have outlived the smoke of battle, the granite monuments, and even the passage of generations.

Dave lays out why those few lines still matter. Lincoln chose his opening deliberately: “Four score and seven years ago.” By reaching back to 1776 rather than 1787, Lincoln grounded the meaning of the Civil War not in the technicalities of the Constitution, but in the promises of the Declaration of Independence. America’s true birth, Bowman argues, was in the declaration of ideals, not the hammering out of legal structures. Jefferson’s words, not Madison’s, gave definition to the nation’s purpose.

Lincoln knew that the war was not only about preserving the Union. It was about testing a proposition: that all men are created equal. By calling equality a proposition, Lincoln admitted that it had not been fully realized in 1776, nor in 1863. It was a standard to aspire to, one that demanded sacrifice and vigilance. As Bowman tells listeners, Lincoln was not asking Americans to fight and die for clauses and articles. He was asking them to fight for the permanence of an idea that liberty and equality are the birthright of all.

Bowman also draws on Jefferson’s radical phrasing of life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness. These were not ornamental words, but a moral compass. Unlike Locke’s emphasis on property, Jefferson’s phrase pointed to something broader, more American, and more action-oriented. By the time of the Civil War, this philosophy became a rebuke to slavery itself, exposing it as a denial of every right the nation was founded to protect.

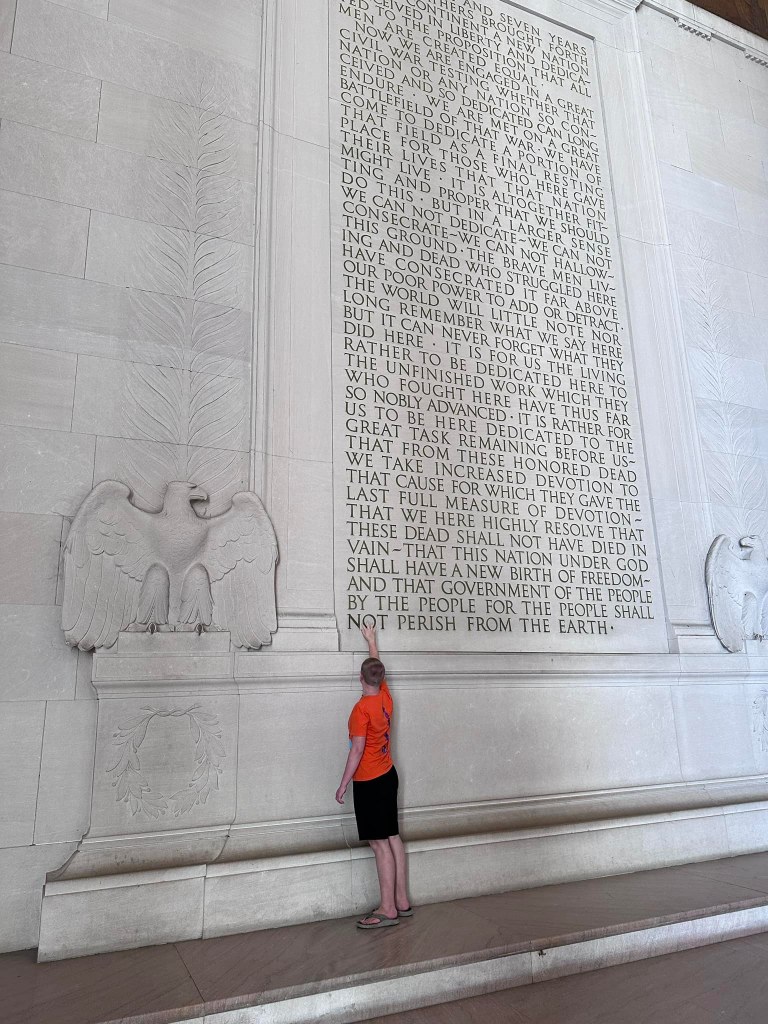

What makes this episode powerful is not only the historical clarity but the personal touch. Bowman recalls taking his son to Gettysburg and to the Lincoln Memorial, where the boy placed his hands on the carved words of the Gettysburg Address. That moment underscored the point of the hour: each generation must rededicate itself to the proposition of equality and to the belief that government of, by, and for the people exists only to secure liberty.

This is not nostalgia, but a call to action. Jefferson’s preamble and Lincoln’s address are not museum pieces. They are a mirror. They ask whether our government today secures rights or tramples them, whether it lives by the consent of the governed or by inertia and coercion. That is the real test.

Leave a comment