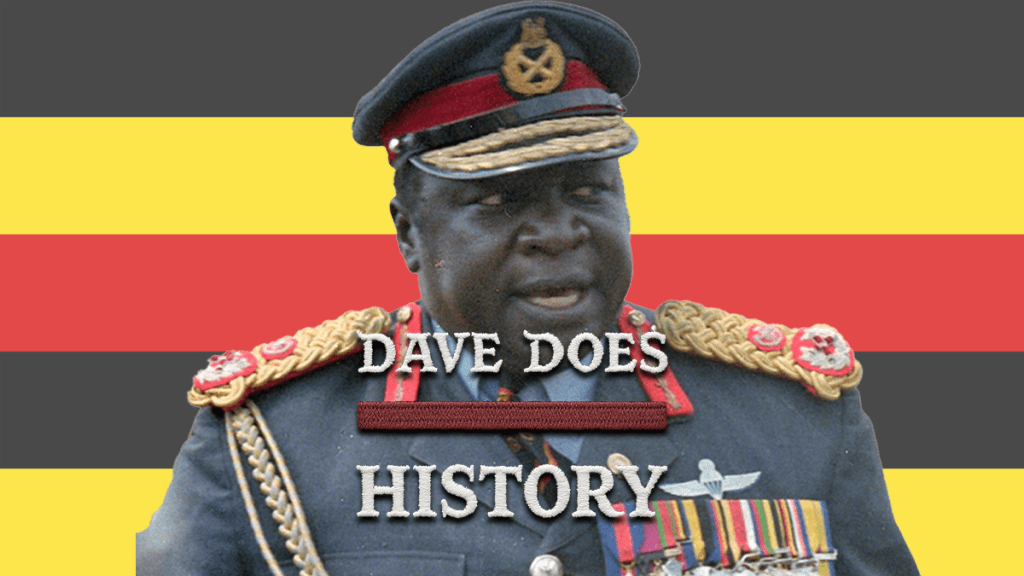

It began with a speech. Not a debate in Parliament, not a carefully considered policy rollout. Just a speech from a man in a military uniform who fancied himself the voice of God. On August 4, 1972, Uganda’s dictator, Idi Amin, announced that the country’s Asian population had 90 days to pack up and leave. Seventy thousand people, most of them born in Uganda, were suddenly strangers in their own homeland.

The order was swift and severe. First it applied to British passport holders of Indian descent. Then it was widened to include citizens of India, Pakistan, and Bangladesh. And then, absurdly, even Ugandan citizens of Asian ancestry were told to get out. That final edict was walked back, technically, after international outcry. But by that time, fear and violence had already done the work. Most of those targeted left, whether they had a Ugandan passport or not. Amin had made it clear that their color, not their papers, was the issue.

The Asians of Uganda weren’t newcomers. They had been brought there under British rule, many as laborers to build the East African railway. After the tracks were laid, some stayed, finding work in trade, finance, and medicine. Over decades, they built a prosperous network of small businesses, shops, farms, and banks. They became part of Uganda’s economic engine, contributing more than their numbers suggested. But their success didn’t sit well with everyone, especially those in power.

Amin used the resentment. He played to the crowd. He told stories of corruption and hoarding, painted Asians as bloodsuckers and parasites. He said they were milking the cow but not feeding it. Never mind that his own military was gutting the country like a butcher with a dull blade. The rhetoric of racial nationalism helped him shore up support where it counted. Among the soldiers. In the streets. Inside his own fragile circle of influence.

What followed the announcement wasn’t orderly deportation. It was chaos wrapped in camouflage. At roadblocks near Entebbe Airport, soldiers beat passengers, took gold and jewelry from frightened families, raped women, and shook down anyone with the audacity to try and leave with dignity. People who thought their citizenship would protect them found their papers torn up on sight. Possessions were seized. Shops, homes, even toothbrushes, gone.

Uganda’s middle class disappeared overnight. In their place, Amin’s cronies took over. Operation Mafuta Mingi, he called it, meaning “Operation Plenty of Grease.” Over five thousand businesses, farms, and estates were handed over to soldiers, bureaucrats, and anyone with the right connections. Some properties were reassigned to state agencies. Others just vanished into the hands of whoever got there first. It was theft, plain and unrepentant.

The economic consequences hit like a hammer. Uganda’s GDP dropped within months. Manufacturing collapsed. The value of salaries shrank into irrelevance. Amin claimed he was putting control into the hands of ordinary Ugandans, but in reality, the shops stood empty and the economy stalled. There were black faces behind the counters now, just as he said, but the goods were gone and so were the customers.

Beyond the numbers, the human toll was staggering. Families scattered across the globe. About 27,000 ended up in the UK, housed first in military camps, then resettled in towns like Leicester. Canada took thousands more. So did India, reluctantly. Some faced new waves of racism when they arrived. Told to go home from one place, and then unwelcome in the next.

And yet, many made it. There’s a stubborn kind of grit in people who lose everything and start again. Ugandan Asians went on to build new lives. Some returned to East Africa decades later, drawn by nostalgia or the promise of restoration under a new government. A few even got their properties back, a sort of reconciliation that couldn’t undo the trauma but at least acknowledged it happened.

Idi Amin ruled with violence, paranoia, and a flair for spectacle. His expulsion of the Asian population was more than just a political stunt. It was an act of racist opportunism, one that hollowed out the country he claimed to love. Uganda has moved on, but the echo of those 90 days lingers in memory. Not just for the people forced to flee, but for the country that never quite recovered from losing them.

Leave a comment