In 1963, President John F. Kennedy found himself pressed up against the walls of history. The ground beneath the country was shifting. Birmingham was burning, Medgar Evers was dead, and the old political calculations no longer worked. For years, Kennedy had walked a careful line on civil rights. He made campaign promises but often stopped short of action that might cost him support in the South. He wasn’t alone in that. Presidents before him had done the same. But 1963 forced a reckoning.

That summer, Kennedy took a risk. He stepped in front of the cameras on the night of June 11 and told the American people something they hadn’t quite heard from a president before. He didn’t talk about votes, or lawsuits, or vague ideals. He called segregation what it was, a moral crisis. And in that speech, he asked the nation to finally live up to its founding promises. “We are confronted primarily with a moral issue,” he said. “It is as old as the scriptures and is as clear as the American Constitution.” Coming from a man who’d been so cautious on the issue, it struck many Americans like a thunderclap.

This wasn’t just a rhetorical shift. Just eight days after that speech, Kennedy submitted legislation to Congress that aimed to do what previous laws had failed to accomplish. It would ban segregation in public accommodations. It would strengthen the federal government’s ability to enforce school desegregation. It would protect civil rights workers and give the Justice Department more teeth. It wasn’t perfect. But it was sweeping. And it had almost no chance of passing in its original form.

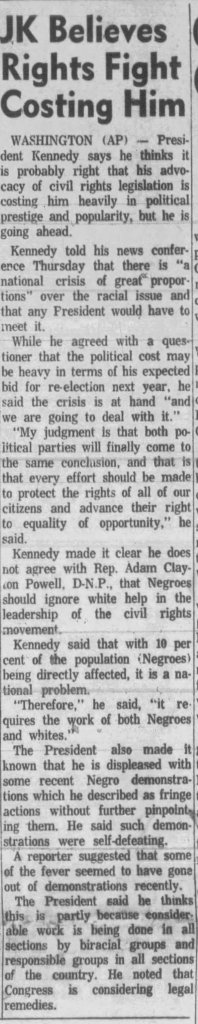

Kennedy knew that. He wasn’t naive. He was aware of the Senate’s southern bloc, the filibusters they could launch, the pressure they could apply. His own advisors warned him that pushing for civil rights might doom his re-election. There were vulnerable Democrats who would be swept away in the backlash. Republicans were already accusing him of pandering. In the South, his name was mud. But he pressed forward anyway. He had seen what had happened in Birmingham, where dogs and fire hoses were turned on children. He had seen the crowds jeering James Meredith when he enrolled at Ole Miss. He had seen Wallace stand in the schoolhouse door.

When Kennedy saw the images from those events, something shifted. It wasn’t sudden, but it was firm. His brother Robert, once viewed as even more cautious than Jack, began talking openly about the stain of racism on the national conscience. There was no longer any safe middle ground. Kennedy’s move toward moral clarity wasn’t universally welcomed, but it was noticed. Even the Fort Collins Coloradoan, hardly a national organ of liberalism, printed the president’s civil rights push prominently on its front page on August 1, 1963. They noted the White House’s desire to keep civil rights front and center in the news, to “keep up the steam,” in the words of one aide. That tells you something. There was no backing down.

By the time the March on Washington arrived in late August, Kennedy had gone from wary participant to partner. He met with organizers, helped ensure the march remained peaceful, and defended its purpose publicly. His administration didn’t sponsor the march, but it didn’t obstruct it either. That was a change. A few years earlier, a gathering like that would have been dismissed as dangerous or radical. In 1963, it became a national turning point.

Kennedy would not live to see the bill become law. It took Lyndon Johnson’s brute political strength and mastery of the Senate to get it passed in 1964. But the work Johnson did leaned on the foundation Kennedy laid. Johnson himself said as much. What Kennedy did that year wasn’t just symbolic. He moved the presidency onto the right side of the issue, and by doing so, he gave moral cover to others who’d been sitting on the fence.

It’s easy to look back now and forget how bitter the fight was. Or how uncertain the outcome. Or how lonely leadership can feel when you’re staring down your own party. Kennedy took a chance that year. He chose to do what he believed was right, even if it cost him votes. It may have. But what he gained, what the country gained, was a clearer vision of what America should be. For that, 1963 remains one of the most defining years of his presidency. And perhaps, the most courageous.

Leave a comment