It was July 20, 1976, and I was twelve years old, glued to the television, breath held, waiting for Mars to say something back. I wasn’t thinking about baseball or summer vacation. I was a space nerd. The kind who had Skylab patches on his notebook and could list every Apollo mission by heart. I lived and breathed NASA. And that day, NASA landed a robot on another planet.

Viking 1 touched down in a place called Chryse Planitia. The first image came in slowly, pixel by pixel. A black-and-white shot of a footpad resting on red soil scattered with rocks. It looked simple. But it wasn’t. That photo was the product of a decade of planning, political will, budget battles, design innovation, and a question older than any space program. Was Mars dead, or was something alive up there?

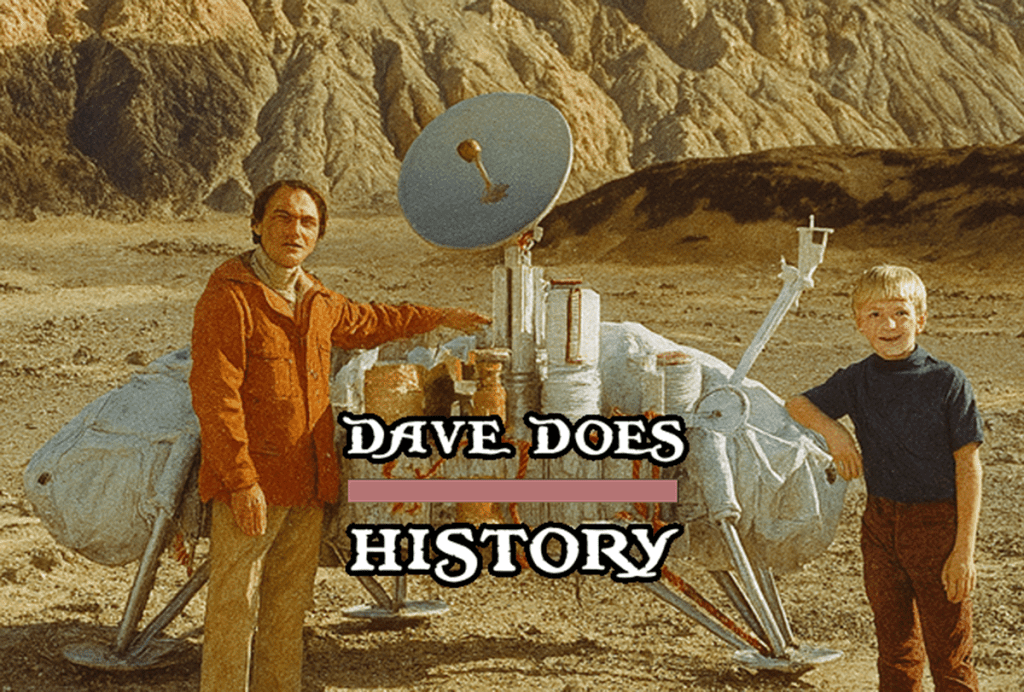

Viking 1 was more than a probe. It was the first time we brought a laboratory to another planet. It was a two-part spacecraft—an orbiter to map and photograph the planet from above, and a lander to set down and dig in. The whole program had evolved from the scrapped Voyager Mars plans, pushed forward by NASA Langley and brought to life by Jet Propulsion Lab and Martin Marietta. It launched on August 20, 1975, riding atop a Titan IIIE-Centaur rocket, and spent eleven months cruising through the void.

Originally, Viking was supposed to land on July 4. The Bicentennial. A perfect PR moment. But the site they picked turned out to be rough terrain, so they waited. They chose a safer area and landed on July 20 instead—seven years to the day after Armstrong stepped onto the Moon. A different world, a different challenge, and no humans onboard. But it still sent shivers down the spine.

The descent was a balancing act between speed and precision. Mars has an atmosphere, but it’s thin. Too thin to use a parachute alone. Viking came in fast, protected by a heat shield. At the right moment, it dropped a parachute, then jettisoned it and fired three descent engines. Not just any engines, either. NASA designed them with 18 small nozzles, meant to spread the exhaust evenly and avoid scorching the surface. They didn’t want to cook the soil they were trying to test. Everything about this landing had to work, or the entire mission would be lost. And it worked. Perfectly.

Once on the surface, Viking 1 became a pioneer. It carried a robotic arm to scoop up Martian soil. It had instruments to test for organics and chemical reactions that might suggest life. The star of the show was the Labeled Release experiment, which mixed nutrients with Martian soil to see if anything would metabolize them. One of the tests lit up. Something in the soil reacted. But the gas chromatograph, which was designed to sniff out organic molecules, found nothing. Other experiments didn’t confirm life, either. The science community was divided. Some, like Gilbert Levin, insisted it was life. Others said it was just chemistry. Carl Sagan, who had helped guide the mission and advocate for those life detection experiments, warned against jumping to conclusions. He reminded everyone that Mars wasn’t Earth, and its rules might be different.

Viking 2 followed Viking 1, launching just a few weeks later. It landed in Utopia Planitia on September 3. It ran the same experiments and found the same confusion. Both landers operated long past their expected lifespans. Viking 1 kept working until 1982. The orbiters mapped almost all of Mars in incredible detail, showing canyons, volcanoes, and signs that water had once carved deep channels into the Martian surface.

The cost was enormous—over a billion dollars at the time, more than seven billion today. But Viking gave us something that money alone couldn’t buy. It gave us our first real taste of another planet. It asked Mars a question and waited for an answer.

The answers were murky, but the legacy was not. Viking was the first to last years on another planet. It taught us how to land with care, how to test without contaminating the sample, how to listen patiently. Every Mars mission that came after—Pathfinder, Spirit, Curiosity, Perseverance—walked in its shadow.

Carl Sagan believed space exploration was how the universe came to know itself. Viking was our first serious effort to do just that. It didn’t tell us if Mars was alive, but it proved that we were. And for a twelve-year-old kid watching that ghostly image appear on a grainy screen, it meant everything.

Leave a comment