It was supposed to be another move. That’s what they told them. Just pack up, bring the children, and come downstairs. There’d be a photograph, they said, to reassure the world that the Tsar and his family were alive and well. But no rescue was coming. There was no train, no caravan, no asylum waiting beyond the Ural Mountains. What was waiting was a room in a basement, a dozen men with pistols, and the end of the Romanov line.

On July 17, 1918, Tsar Nicholas II, his wife Alexandra, their five children, and four loyal attendants were murdered in cold blood by Bolshevik agents in the city of Yekaterinburg. It was not a battle. It was not justice. It was not a trial. It was extermination. The execution was ordered in secret by men who feared the symbolic power of a wounded monarchy more than they feared eternal damnation. It was the kind of act that doesn’t just kill people. It buries history.

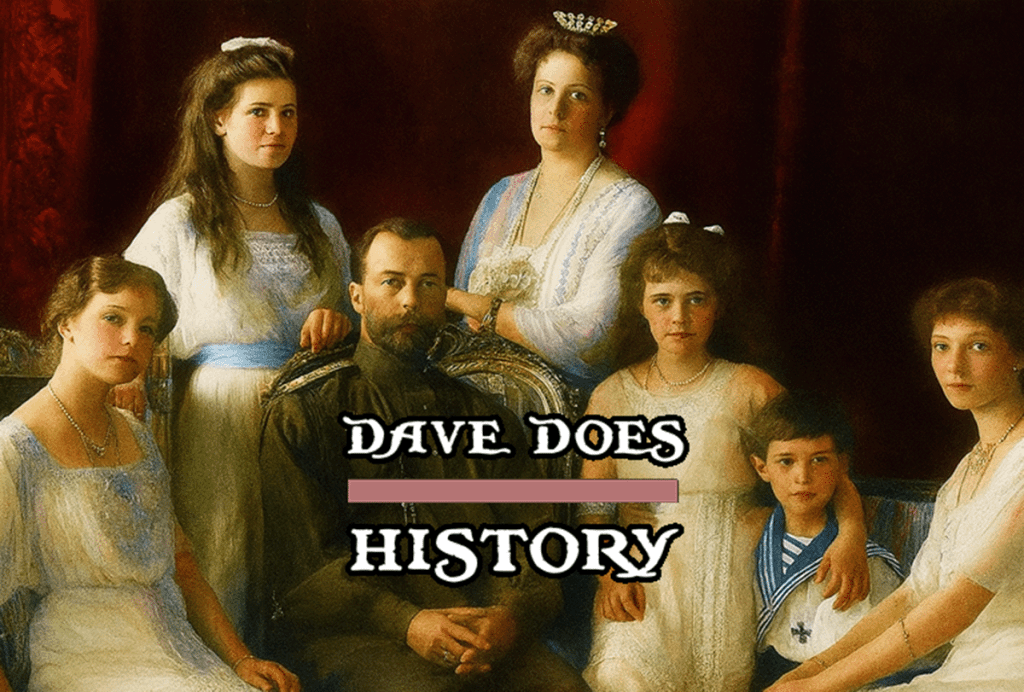

Nicholas Romanov had never been comfortable wearing the crown. Even as a young man, he admitted to those close to him that he never wanted to rule. He wasn’t trained for the job and didn’t have the temperament for it. But he believed the Tsar’s authority came directly from God, and he saw it as his sacred duty to carry it out, however imperfectly. He was a devoted father and husband. He wasn’t a visionary, or even particularly effective, but he wasn’t a monster. That label belonged to others.

His reign was marked by missteps and missed chances. The failed war against Japan. The 1905 Revolution. Bloody Sunday. His stubborn resistance to constitutional reforms. And yes, his disastrous decision to drag Russia into the First World War, a war the country was completely unprepared to fight. By 1917, Russia was falling apart. Food was vanishing from cities. Soldiers were deserting. The people had lost faith, and Nicholas was forced to abdicate.

He and his family were shuffled from one guarded house to another, eventually landing in the Ipatiev House, grimly renamed “The House of Special Purpose.” That’s where the Bolsheviks kept them under lock and key, stripping away their dignity piece by piece. Windows were sealed shut. Guards played revolutionary songs on the family’s own phonograph. Looting, graffiti, humiliation. The Romanovs were mocked, starved, and isolated. The imperial daughters were told not to look out the window. When Anastasia once tried, a guard fired a shot at her head.

The new regime, led by Lenin and his hardliners, wasn’t interested in fair play. They saw Nicholas and his family not as human beings, but as threats to the revolution. Symbols. And symbols had to be erased. The Bolsheviks feared that the advancing White Army, made up of anti-communist forces, might liberate the family and use them as a rallying point. That fear, more than anything, sealed the Romanovs’ fate. Local Soviet leaders wanted them dead. And whether Lenin gave the direct order or merely looked the other way, the murder was carried out with cold determination.

They were told to dress. They were led to the basement. They stood, arranged as if waiting for a family portrait. And then it began. The guards opened fire. Smoke filled the room. Screams echoed against the concrete. The bullets didn’t kill everyone. The children, wearing jewels sewn into their corsets, were hard to kill. The bayonets were brought out. Then the butts of rifles. And finally silence.

The bodies were stripped and mutilated, burned with acid, and buried in secret graves in a forest. For decades, the Soviet government denied what had happened. Lied about it. Covered it up. The truth trickled out in whispers and exile memoirs, in buried documents and DNA analysis. When the remains were finally found and identified in the 1990s, they were given a proper funeral and reburied in St. Petersburg. But that solemn gesture could never undo the crime.

Some people today try to justify it. They say it was wartime. They say the revolution was necessary. They say the Tsar was weak, and the people had suffered. All of that may be true. But none of it justifies the murder of children. None of it justifies lining up a sick boy and his sisters in a basement and turning them into corpses to feed an ideology.

The death of the Romanovs wasn’t just a political execution. It was a signal. A declaration. The old world was dead, and a new, blood-soaked one was being born in its place. One where power came from the barrel of a gun, not the weight of history. The Russian people didn’t just lose a monarch that night. They lost a connection to the past, a sense of identity, a spiritual anchor.

What happened in that basement in Yekaterinburg is more than a historical tragedy. It’s a warning. When revolutions stop seeing people as human and start seeing them only as obstacles, it never ends with ideas. It ends with bodies.

And the ghosts never leave.

Leave a comment