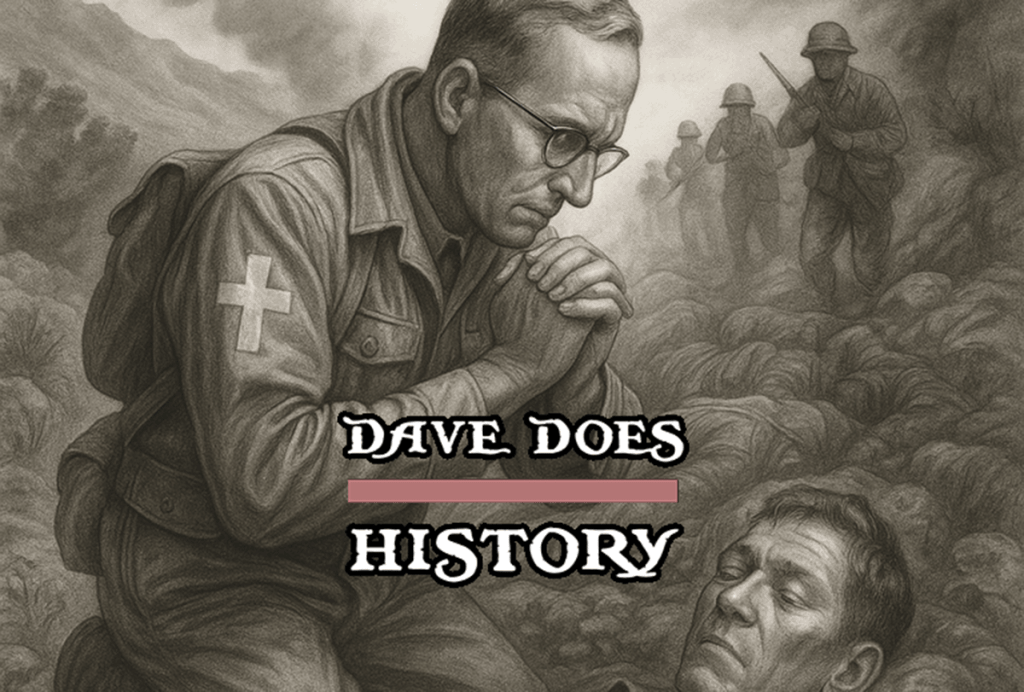

They found him kneeling.

It was July 16, 1950. On a Korean hillside, just above the village of Tuman, the war had already turned savage. American troops were in full retreat. The 24th Infantry Division had been thrown into the fight barely two weeks after the North Korean invasion, tasked with slowing down the Communist advance long enough for reinforcements to arrive. It was a desperate mission. Most of the men had no combat experience. Their equipment was leftover from the last war. And now, after being overrun at the Kum River, they were running for their lives.

But not all of them could run. Around thirty American soldiers from the 19th Infantry were too badly wounded to be moved. The terrain was rugged and steep. Their comrades tried to carry them through the mountains, but exhaustion set in. Eventually, the order came to leave the worst of the wounded behind. Someone else would have to come back for them, if that were even possible.

Two men volunteered to stay. Neither of them carried a weapon. Captain Linton Buttrey, a medic, wore a Red Cross on his arm. And Father Herman Felhoelter, a Franciscan priest and Army chaplain, wore a white Latin cross, marking him as a man of faith, not war. Both were protected under the Geneva Convention. Both knew that staying behind could mean death.

As twilight gave way to night, they waited with the dying. When a patrol from the North Korean People’s Army came up the trail, Felhoelter told Buttrey to run. The medic tried. He was shot in the ankle but managed to crawl into the woods. The priest stayed. He knelt down beside one of the wounded men and began to pray.

Through binoculars, American soldiers hidden in the hills nearby watched what happened next. The North Korean troops, mostly young and jittery, armed with Soviet rifles and burp guns, opened fire. They shot Father Felhoelter first, in the back and head as he prayed over a soldier. Then they turned their weapons on the helpless wounded, killing all thirty.

There was no firefight. No resistance. Just murder.

This moment, later named the Chaplain–Medic Massacre, became one of the earliest and most brutal atrocities of the Korean War. It was shocking not just for its cruelty, but because it targeted men who posed no threat. These were not combatants. These were broken bodies on stretchers. And a chaplain, kneeling with them, praying.

The aftermath was chaotic. American forces never fully regained control of that area. Of the thirty-one victims, only three bodies were ever recovered, including Father Felhoelter’s. For his sacrifice, he was awarded the Distinguished Service Cross posthumously. Buttrey survived and testified before Congress three years later, describing the massacre in detail.

What kind of man stays behind to die with the wounded? Herman Felhoelter was born in Louisville, Kentucky, in 1913. He was a parishioner at St. Martin of Tours. He became a Franciscan priest in 1939, served as an Army chaplain in World War II, and returned to civilian life afterward. But when the storm clouds gathered again in the late 1940s, he put the uniform back on. He was assigned to the 19th Infantry Regiment in Korea.

Just four days before his death, he wrote to his mother, “Don’t worry, Mother. God’s will be done. I feel so good to know the power of your prayers… I am happy in the thought that I can help some souls who need help.” That letter would be the last she received.

Back home, the military initially listed him as “missing in action.” But the truth was already known. Witnesses had seen him gunned down in prayer. A photo of him kneeling was never taken, but the image lives on in every soldier who ever needed a chaplain in their darkest hour. His body now lies in St. Michael Cemetery in Louisville.

The massacre did more than take lives. It galvanized the U.S. Army to form a commission to investigate war crimes in Korea. It was one of the cases reviewed by Senator Joseph McCarthy’s committee in 1953. It raised awareness about the need for clear policies on the treatment of prisoners and wounded. And it raised questions North Korea never answered.

No one was ever held accountable.

Father Felhoelter was the first chaplain to die in Korea. He would not be the last. His death prompted Cardinal Spellman to call for more Catholic chaplains to serve during the war. His name was later inscribed on Chaplains Hill in Arlington National Cemetery, alongside others who gave their lives in spiritual service during wartime.

There’s a reason this story matters. We talk often about heroes who charge into battle, who pull comrades from burning tanks or storm enemy bunkers. But there are other kinds of heroes. The quiet kind. The ones who stay behind. The ones who don’t carry weapons but carry hope.

Herman Felhoelter did not raise a rifle. He raised a prayer.

And in that moment, when the world descended into violence all around him, he held his ground. Not with bullets. Not with orders. But with faith.

That kind of courage does not vanish. It lingers in stories like this. It echoes in every field hospital, in every whispered prayer on a battlefield, and in every chaplain who walks into danger armed with nothing but conviction.

The Korean War left many wounds, many questions, and many ghosts.

But it also gave us men like Father Felhoelter.

May we never forget what he gave. Or how he gave it.

Leave a comment