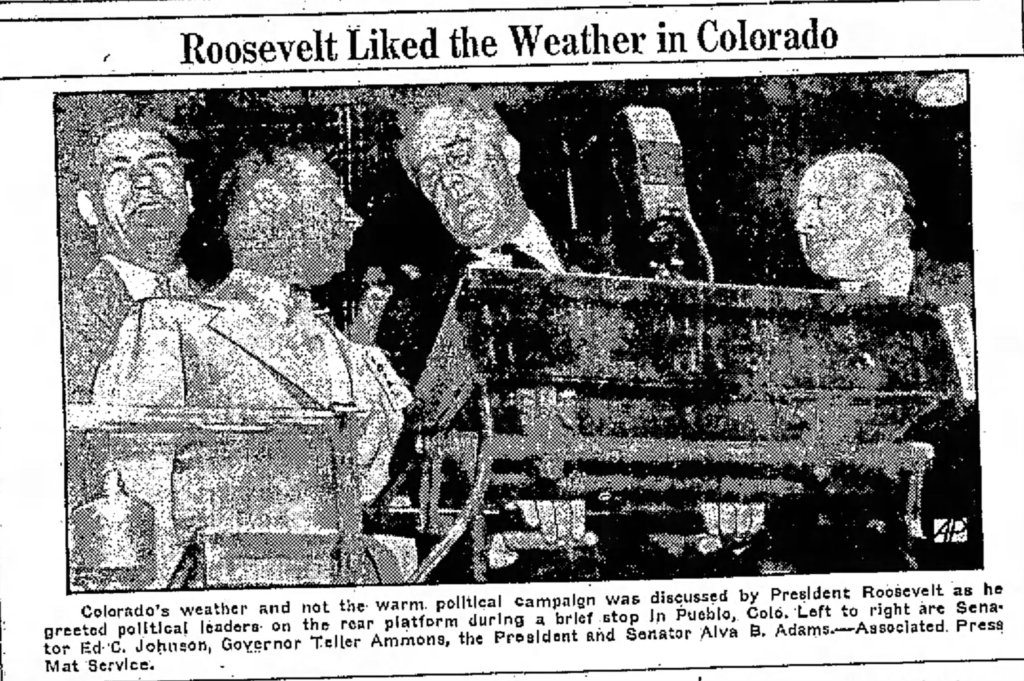

It was July 12, 1938, and the President of the United States was in Pueblo, Colorado. But he wasn’t in a grand hall or behind a White House lectern. He was on the back of a train, standing on the rear platform, framed by the open air, iron railings, and a cluster of microphones. Franklin Delano Roosevelt had rolled into town with a message, and he delivered it the way he liked best, straight to the people, eye to eye and heart to heart. The whistle-stop tour was pure Roosevelt. He smiled, he waved, he cracked wise about the weather. But tucked into his short remarks that day was a line that still echoes: “We want to make democracy work.” It was a bold phrase for a President in motion, delivered not from a throne of marble, but from a train car. And the meaning behind those words deserves more than just a passing glance.

To understand what Roosevelt meant, you have to understand what was happening in America at the time. The country was still climbing out of the Great Depression, and the ground beneath its feet wasn’t stable. Unemployment had dipped, then crept back up. Business leaders were nervous. Labor strikes were flaring. The nation’s economy had hiccuped again in what came to be known as the Roosevelt Recession. Overseas, fascism was on the march. Hitler had already swallowed Austria. Mussolini was barking from Rome. Stalin was purging anything that looked like dissent. In many places, democracy had failed or was failing. It looked inefficient, slow, uncertain. Totalitarian regimes promised order and results. Roosevelt wanted to prove that democracy could deliver too.

But when Roosevelt said, “We want to make democracy work,” what was he really saying? For him, it wasn’t just about voting booths or parliamentary procedures. It was about action. It was about getting things done. He pointed to dams, roads, electrification, and massive public works funded and managed by the federal government. He talked about how the government had touched lives in ways it never had before. To him, democracy wasn’t simply the right to vote or speak your mind. It was a system that should provide jobs, food, housing, and dignity. In his view, if democracy didn’t do those things, it risked falling behind more aggressive systems that promised they could.

This raises a harder question. Was democracy not working in 1938? If you asked a small business owner in Iowa, or a farmer in Oklahoma, you might hear that it was working just fine before the federal government got involved in every corner of life. But to Roosevelt, the slow pace of traditional democracy was unacceptable in a time of crisis. He wanted to push, to build, to make government a muscular engine of change. His frustration with limits had already shown itself in his court-packing scheme the year before. He was trying to bend the machinery of the republic to meet his vision. The people of Pueblo may have heard a cheerleader that day. But under the surface, Roosevelt was laying out a challenge to the way America had always done things.

And that is where the more traditional view radar starts flashing red. Because this was not the vision of democracy that the Founding Fathers had in mind. The Constitution was built to restrain power, not to concentrate it. Liberty, in the classical American sense, is not something government gives you. It’s what you already have by right, and what government exists to protect. Roosevelt flipped that script. He saw the government not as a referee but as a player on the field, shaping outcomes and leveling the score. His version of democracy was hands-on, top-down, and deeply involved in every American’s daily life.

That vision carries consequences. Once you define democracy as something that should actively provide for people, you open the door to endless promises. Every election becomes a bidding war. Every crisis becomes a reason to expand federal reach. And soon, the people stop seeing themselves as citizens and start seeing themselves as clients. Roosevelt didn’t say this out loud in Pueblo, but it’s embedded in the idea that democracy must be made to work, as if it were a machine that needed fixing by experts in Washington.

He didn’t invent this mindset, but he mainstreamed it. He dressed it up in patriotic language and made it feel like common sense. But when politicians start talking about making democracy work, it’s fair to ask what exactly they mean. Do they mean protecting the right of the individual to pursue happiness without interference? Or do they mean using the weight of the state to engineer outcomes they believe are fair or efficient? That is not a semantic difference. That is the difference between freedom and control.

And so we return to that train car in Pueblo. Roosevelt smiled and talked about the weather, but he was also selling a philosophy. The scenery rolled by behind him, mountains and farmland and the raw backbone of America. He told the crowd that democracy could deliver. But what kind of democracy was he offering? Not the slow, deliberative republic of Washington and Madison. This was something newer, faster, and much more involved in daily life.

Looking back, we can see the fork in the tracks. One path leads toward a government that protects freedom and leaves people alone to build their own lives. The other leads toward a government that promises more, delivers selectively, and never stops growing. Roosevelt believed he was saving democracy. Many today believe he was rebranding it.

Either way, the Arkansas River still flows through Pueblo, shaped by the land, not by decree. It moves according to its nature, not by force. So does liberty, if we let it. It doesn’t need to be engineered. It needs to be respected. And that is the kind of democracy that truly works.

Leave a comment