It was just past 11 p.m. on a steamy June 25, 1906 when Harry Kendall Thaw, millionaire playboy and professional lunatic, stood up from his table at the rooftop theatre of Madison Square Garden. The show, a light musical romp called Mam’zelle Champagne, was wrapping up. The crowd was cheerful, a little drunk, and completely unprepared for what was about to happen. Across the room, at his usual table, sat the man Thaw hated more than anyone on earth. Stanford White, the famous architect, the designer of the very building they were in, was taking in the show without a care in the world. That’s when Thaw pulled out his pistol, walked up to him, and shot him three times in the face.

For a moment, the audience thought it was part of the act. High society had a twisted sense of humor in those days. But this wasn’t theater. Stanford White was dead before he hit the ground. His head was a mess of blood, powder burns, and shattered bone. Thaw, ever the gentleman, waved the gun in the air and shouted, “I did it because he ruined my wife!” Or maybe it was “my life.” Reports differ. Either way, Evelyn Nesbit was at the center of it all.

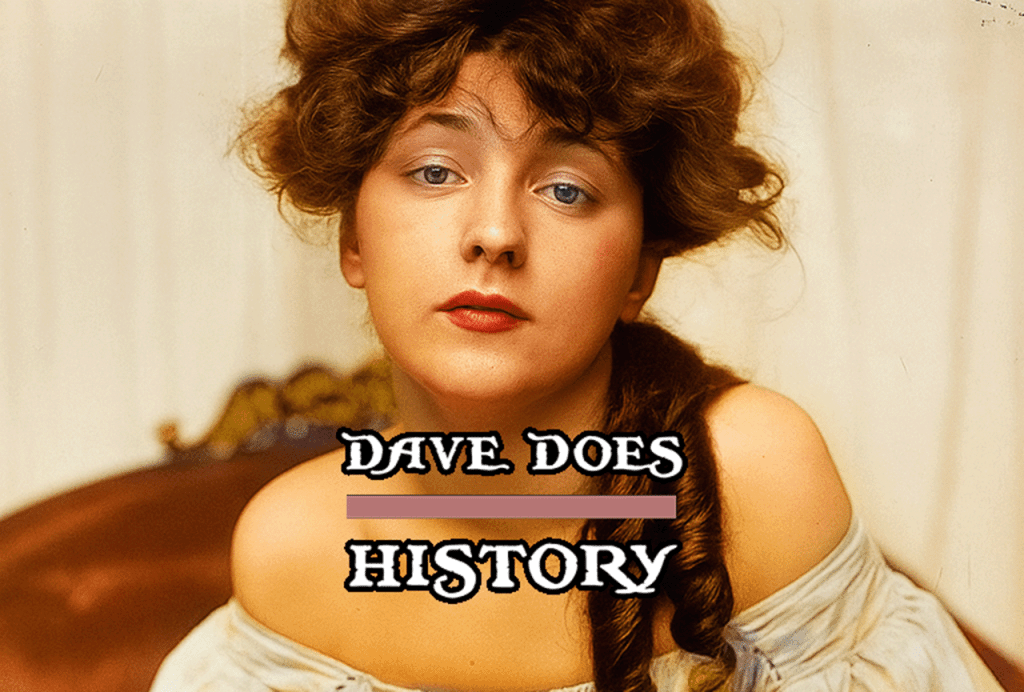

Evelyn was the very picture of the Gilded Age beauty. She was a teenage model with a face that sold everything from Coca-Cola to Prudential Insurance. She’d started out poor, clawed her way into the spotlight as a chorus girl, and ended up the obsession of powerful men. First came Stanford White, nearly 30 years her senior, who groomed her under the guise of mentorship. He moved her family into a fancy hotel, paid for her brother’s schooling, and, according to Evelyn, raped her while she was unconscious after a night of champagne and flattery. What followed was a strange and deeply troubling relationship that blurred the line between victim and companion. Then came Harry Thaw.

Thaw was rich, unstable, and obsessed. Born into a Pennsylvania railroad fortune, he’d spent his early life getting thrown out of schools, terrorizing servants, and lighting cigars with hundred-dollar bills. By the time he met Evelyn, he was addicted to morphine and cocaine, carried a whip, and fancied himself a moral crusader. He believed he had a divine mission to avenge women wronged by the corrupt elites of New York City. And he believed that Stanford White was the worst of them.

He met Evelyn backstage, calling himself “Mr. Munroe” and pretending to be a modest admirer. Once he revealed his true identity as the Thaw heir, he poured money and gifts on her like a flood. But what he wanted wasn’t love. He wanted purity. Chastity. He wanted her to be untouched, something she couldn’t be. When Evelyn finally told him the full story of her time with White, Thaw became unhinged. On a trip to Europe, he locked her in a castle, beat her, and then begged her to marry him. She eventually did. Maybe it was for financial security. Maybe it was trauma. Maybe she believed there were no better options.

Whatever the reason, the marriage didn’t calm Harry down. He wrote letters to anti-vice crusaders. He convinced himself that White had hired gangsters to kill him. He started carrying a gun everywhere. And then, on June 25, 1906, he put his fantasy into action.

The fallout was explosive. White’s death was just the opening act. What followed was a media frenzy that made O.J. look like a school board hearing. The newspapers called it the “Trial of the Century.” Reporters camped outside the courthouse. Sob Sisters poured out sentimental drivel about Evelyn’s lost innocence. The prosecution wanted a quiet deal. The defense pushed for insanity. The whole thing became a circus.

At the first trial, the jury couldn’t agree. Seven voted guilty, five not guilty. Thaw had a meltdown in his cell and accused everyone of conspiring to declare him mad. The second trial went smoother. His new lawyer painted him as a man temporarily driven insane by the trauma of his wife’s defilement. It was labeled “Dementia Americana” by the press—a uniquely American insanity brought on by outrage over female purity. The jury bought it. Not guilty by reason of insanity. Thaw was sent to Matteawan, a hospital for the criminally insane. Not prison. Not death row. A place where his family’s fortune ensured he could drink champagne, sleep in a brass bed, and have a doctor on call.

Evelyn testified at both trials. There were whispers that she was paid handsomely for her cooperation. But she didn’t exactly end up rich. Thaw’s family never fully delivered on their promises. Her career fizzled. She tried writing. She made a few films. But she was never able to escape the shadow of the murder that made her famous.

Stanford White, the man whose buildings helped define an era, was buried with quiet dignity. But his legacy took a hit. Stories of his private life came pouring out. The tower room with the swing. The teenage girls. The black book. He wasn’t tried in court, but the court of public opinion rendered its verdict. In some eyes, Thaw had done the world a favor. In others, he was just a madman with a gun.

In the end, everyone lost. White lost his life. Evelyn lost her future. Thaw lost whatever was left of his mind. But the story stuck. A murder on a rooftop. A beauty in distress. A madman with a gun. It was America’s first great tabloid scandal, and it set the tone for everything that came after.

In a time when opulence masked rot and morality bowed to power, the rooftop at Madison Square Garden became a stage for a very American kind of tragedy. Not just because of who died, but because of why, and how many people watched it happen and thought it was just part of the show.

Leave a comment