The morning of June 18, 1815, broke damp and heavy with the scent of churned mud and spent gunpowder. South of the quiet village of Waterloo, Belgium, two great ridges faced one another across a narrow valley, each bristling with men and iron. The ground, soaked by a night of rain, sucked at boots and wheels alike. The air hung with tension. The clouds were lifting, but thunder of a different kind would soon follow. On one side stood Napoleon Bonaparte, the Emperor returned from exile, mounted on a gray stallion and wrapped in the weight of old glory. On the other, the Duke of Wellington’s lines stood silent behind the rise, hidden from sight, dug into the earth like an English bulldog waiting for the right moment to bite. Cannons sat in mud, cavalry readied their sabers, and infantry braced to hold or die. The Battle of Waterloo was about to begin.

By the end of the day, Europe would change forever.

Waterloo was no ordinary battle. It was the climactic confrontation of more than two decades of bloodshed that had begun with the French Revolution and spiraled into the globe-spanning Napoleonic Wars. Napoleon’s defeat at Waterloo wasn’t just the end of a campaign. It was the end of a myth. For nearly twenty years, the little Corsican had defied monarchs, rewritten laws, shattered armies, and crowned himself Emperor. His name struck fear in the hearts of old regimes and fired the imaginations of men who saw in him the future of merit and revolution. But on that Sunday in June, the weight of the world closed in on him. One last time, he rode to war to stake everything. His reputation. His empire. His very legacy. And he lost it all in a single, brutal day.

They say history turns on a dime. At Waterloo, it turned on the soaked timbers of Hougoumont, on the stubborn square formations of British infantry, on the slow but steady arrival of the Prussian army. It turned on foggy communication, on the hesitation of Ney, on the blindness of Grouchy, and on Napoleon’s unwillingness, perhaps inability, to see that the age of the eagle was over. His enemies had learned from him. They’d adapted, they’d organized, and they were no longer afraid. He was no longer facing monarchs clinging to old order. He was facing Wellington and Blücher, men who understood the art of modern war. Men who knew how to absorb a blow and return one in kind.

But was it inevitable? Could the old master have pulled off one more miracle, as he had so many times before? Or was this battle the unavoidable result of pride, exhaustion, and a crumbling empire held together by memory more than might? Some say Napoleon was already defeated before a single shot was fired, undone by the mathematics of coalition, by the weariness of his nation, by his own failing health. Others argue that Waterloo was lost in inches, in the sodden ground that delayed his artillery, in the walls of La Haye Sainte, in the mistake of underestimating the enemy once too often.

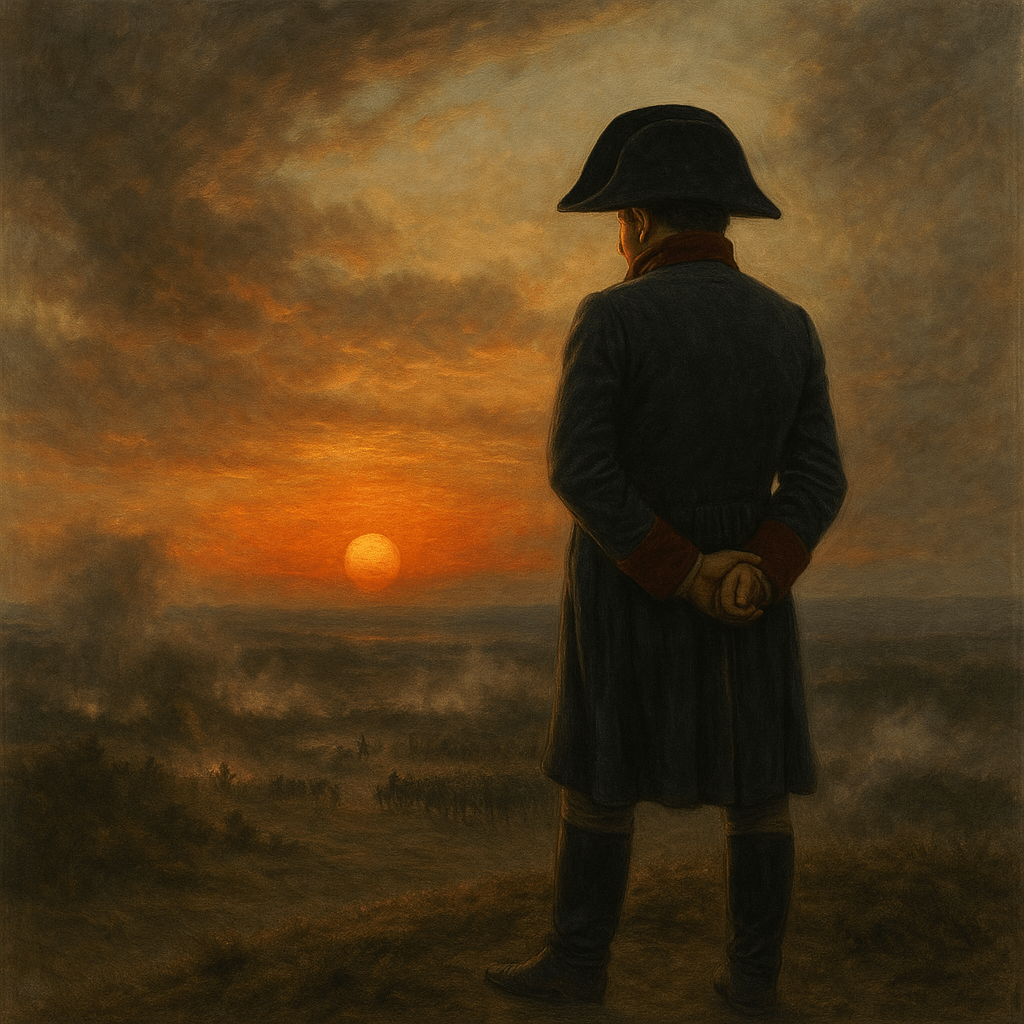

What is certain is this: by nightfall, the French army was in ruins. Napoleon’s star had fallen. And the world had seen the shadow of the eagle vanish into the smoke.

“History is a set of lies agreed upon.”

Napoleon

In the spring of 1814, it seemed the nightmare was finally over. After years of war that had redrawn the map of Europe in blood, Emperor Napoleon Bonaparte abdicated the throne of France. Hounded by defeat, cornered by the Allied powers, and deserted by much of his government and military, Napoleon surrendered his empire and accepted exile on the Mediterranean island of Elba. The once-invincible general, who had marched across the continent like a force of nature, was reduced to ruler of a rocky outpost not much bigger than a French department. Europe exhaled for the first time in decades. Monarchs restored their crowns, diplomats shook hands in Vienna, and the world dared to imagine peace.

But Napoleon was not finished. Not yet.

On March 1, 1815, a ship landed near Cannes. A small figure in a gray coat stepped onto French soil once more. With him came just over a thousand loyal troops, hardly an army. But what followed was nothing short of a political earthquake. As Napoleon marched north toward Paris, regiment after regiment sent to stop him instead joined him. Soldiers cheered. Officers saluted. The Bourbon king, Louis XVIII, fled without firing a shot. By the time Napoleon reached the capital on March 20, the people were chanting his name in the streets. The Hundred Days had begun.

His return was a bombshell. The ink was barely dry on the peace treaties of the previous year. The crowned heads of Europe had just finished congratulating themselves at the Congress of Vienna. Now, the man they had all tried to bury was back on the throne of France. The reaction was swift. Within days, Britain, Prussia, Austria, and Russia declared him an outlaw and formed what would be known as the Seventh Coalition. Their goal was clear: crush Napoleon before he could solidify his power.

Napoleon understood the odds. He knew the numbers didn’t favor him. The combined Coalition could field nearly 800,000 troops, while France, exhausted by years of war, could barely muster a fraction of that. But Napoleon had never been a man to wait and defend. His only chance was to strike first, with speed and precision. He hoped to split the Allied armies in Belgium before they could join forces. If he could defeat the British and the Prussians separately, he might force the rest of the Coalition to the table. It was the old playbook: divide and conquer. But this time, he had less room for error and far fewer loyal marshals at his side.

He chose the Army of the North for this final gamble, a force of roughly 125,000 men, made up of veterans, new recruits, and officers returning from foreign captivity. It wasn’t the Grande Armée of old, but it still packed a punch. On June 15, he crossed the frontier into Belgium and launched what would become the Waterloo campaign.

Across the field stood the men charged with stopping him.

The first was Arthur Wellesley, the Duke of Wellington. A creature of discipline and habit, Wellington was everything Napoleon was not: cautious, unflappable, and suspicious of flair. He had earned his reputation in the Peninsular War, where he had ground French forces down in a war of attrition across Spain. Wellington wasn’t one for dramatic flourishes, but he knew how to make a stand, how to hold ground under fire, and, most importantly, how to keep a coalition army together when national interests threatened to pull it apart.

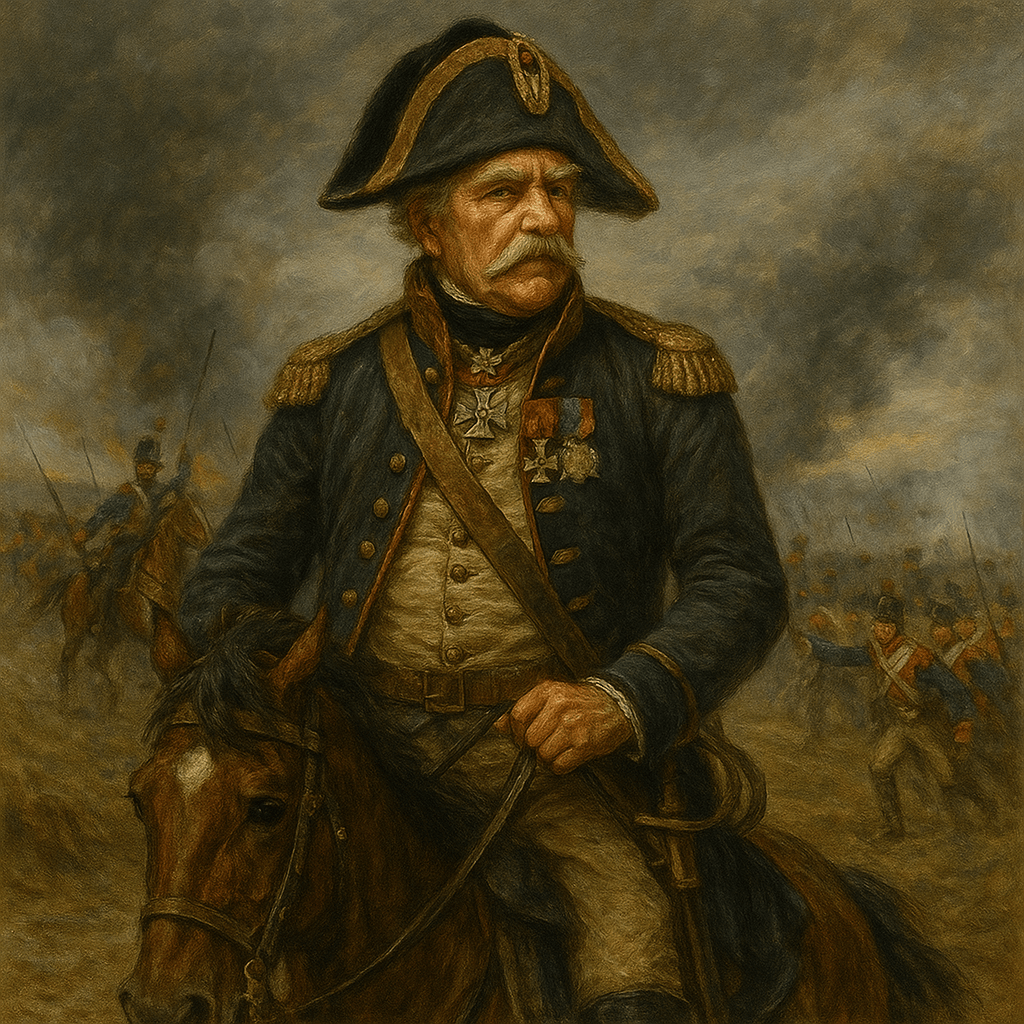

Then there was Gebhard Leberecht von Blücher, the 72-year-old Prussian commander who had once said he wanted to hang Napoleon “like a dog.” Blücher was tough as nails, loved by his men, and often reckless to a fault. But he had something most generals lack: sheer, unshakable tenacity. Even when wounded or outnumbered, Blücher kept fighting. At Ligny, he would take a horse shot out from under him. At Waterloo, he would ride through the night to keep a promise to Wellington. Blücher had been broken before, but never defeated.

The stage was set for one of the most dramatic confrontations in military history. Napoleon had the advantage of movement, of surprise, of tactical genius. But his enemies had learned his tricks. More importantly, they had something to prove too. Wellington had never faced Napoleon in the field. Blücher had lost to him more than once and wanted revenge. The Allies were not just defending their thrones. They were trying to bury the ghost of revolution that Napoleon represented. They wanted Europe put back in its box.

Napoleon’s plan, in the abstract, was sound. He would strike north into Belgium, wedge himself between the British and Prussian armies, defeat them in detail, and force the Coalition to negotiate before the Austrians and Russians could even arrive. He moved with speed and precision, catching both Wellington and Blücher off guard. On June 16, he beat the Prussians at Ligny. At the same time, Marshal Ney clashed with Wellington’s advance guard at Quatre Bras. The result was a draw, but Wellington was forced to retreat north.

The French emperor was close to victory. But even a genius cannot win without cohesion. Grouchy failed to pursue the Prussians effectively. Ney squandered opportunities at Quatre Bras. Napoleon himself seemed slower, more cautious, less decisive than in his prime. Whether due to illness, fatigue, or age, he no longer struck with the same confidence. On the morning of June 18, he delayed his attack until the ground dried. That delay would prove fatal.

As the sun rose over the muddy fields of Waterloo, three commanders prepared for battle. Napoleon, the legend on the brink. Wellington, the rock of steadiness. Blücher, the fury of vengeance. Each carried with him the hopes of nations. Each knew that what happened on that day would echo through history. Europe was on edge. The eagle was circling. And the world held its breath.

Waterloo is a battle of the first rank

Victor Hugo

won by a captain of the second

The field of Waterloo was deceptively ordinary. Just a stretch of Belgian farmland, gently rolling and crisscrossed with cart tracks, shallow ridges, and small farms with names that would soon be etched in military legend: Hougoumont, La Haye Sainte, Papelotte. But on the morning of June 18, 1815, it became the hinge of history. Here, in these soaked and stubborn acres, the fate of an empire would be decided.

Waterloo lay just south of Brussels, a key logistical hub for the Allied powers. Whoever controlled that crossroads controlled access to the heart of Belgium and, beyond that, the road to Paris. Napoleon chose his ground carefully. If he could smash Wellington’s army before the Prussians regrouped, he could force Britain to the negotiating table. If he could roll up the Allied lines, there was a chance, just a chance, that he might reclaim more than his crown. He might reclaim France’s pride. Victory could shatter the fragile Seventh Coalition, expose cracks between Britain and Prussia, and give Napoleon the diplomatic breathing room he so desperately needed.

But the terrain offered no favors.

The battlefield stretched barely two and a half miles across, hemmed in by woods, hedgerows, and muddy paths that funneled troops into choke points. Wellington’s men occupied the northern ridge of Mont-Saint-Jean. It wasn’t high, but it was enough. Behind that ridge, he kept most of his forces hidden, shielded from direct artillery fire. Out front, he placed outposts at key farmhouses. Hougoumont on the right was a brick fortress of sorts, walled and sturdy. La Haye Sainte held the center like a keystone, and Papelotte to the left anchored the line, guarding the route the Prussians were expected to use.

The French set up on the opposing ridge to the south, centered near a farmhouse called La Belle Alliance. From there, Napoleon could survey the battlefield and direct his forces. He had 246 guns and nearly 72,000 men, an army hardened by war and loyal to the man who had brought them back from disgrace. But not all was well. The night before the battle, a violent storm had lashed the countryside. Roads turned to mire. Artillery sank up to its axles. Gunpowder got wet. Men and horses alike stood shivering under canvas, soaked to the bone.

The rain did more than dampen morale. It delayed the fight. Napoleon, relying on fast-moving artillery and cavalry, had to wait for the ground to dry enough for the guns to be mobile. That delay, several hours, was a gift to Wellington. Every minute gave Blücher’s Prussians more time to regroup and march west. And every minute that passed made Napoleon’s window of opportunity smaller.

Napoleon had planned for a short, decisive engagement. Break Wellington early, before Blücher could arrive. But the terrain conspired against him. His men had to march uphill, across mud, into fire. The British lines, camouflaged behind the crest of the ridge, could not be accurately targeted until it was too late. His cavalry found themselves charging blind into prepared squares, bristling with bayonets. The farmhouse strongpoints bled French momentum. Hougoumont in particular became a sinkhole of French strength, swallowing thousands of men in a fruitless, day-long siege.

But for all its difficulties, Napoleon knew the rewards of success were enormous. If he shattered Wellington’s army and forced a British retreat, he could then turn his full might against Blücher and destroy the Prussians before the Austrians and Russians even crossed the Rhine. Paris would be safe. The French people, tired of Bourbon incompetence and drawn once again to the myth of the Emperor, might rally behind a second Napoleonic Empire. His enemies might splinter. He had pulled off miracles before. Why not one more?

This wasn’t just a battle over dirt. It was a battle over destiny. Napoleon saw the field of Waterloo as his redemption, the final page of a story he refused to let anyone else write. And yet, as he looked out over the foggy ridges and muddy fields that morning, perhaps even he felt it, how unforgiving this ground would be, how narrow the margins, how little room remained for error.

Waterloo was a gamble. The stakes were empire. The terrain was no ally. The weather had chosen sides. And time, as it turned out, was not on Napoleon’s.

When Napoleon surveyed his army on the morning of June 18, 1815, he must have felt a flicker of old confidence. Before him stood the Army of the North, roughly 73,000 men, many of them veterans, fiercely loyal to their Emperor. For all its imperfections, it was the best army he had commanded since the disasters of Russia in 1812. While time had weathered the man, the core of his military machine still packed the kind of punch that had once leveled kingdoms.

His men were seasoned and spirited, a blend of grizzled old hands and fresh recruits eager to prove themselves. The heart of his force lay in its morale. These were soldiers who had followed Napoleon into fire and frost, men who believed that one more victory could restore the empire. But there was tension too. Many veterans mistrusted those who had served under the Bourbons and now returned to Napoleon’s side. It was an army both formidable and fragile, capable of brilliance but vulnerable to fracture if the tide turned against them.

Napoleon’s artillery corps was massive, 246 guns in total. French gunnery had always been a strength, and Napoleon had long relied on the mobility and shock power of his “grand battery.” The guns could devastate tightly packed infantry and tear holes in the enemy line. But the heavy rain the night before had slowed their movement. The muddy ground turned batteries into stationary targets. Where once speed had been his ally, now the mud dragged him down.

His cavalry was divided into heavy and light divisions, including the famous cuirassiers, armored horsemen who thundered into battle like knights of old, and swift hussars and chasseurs à cheval who darted along flanks and scouted the field. The cavalry would play a central role during the battle, particularly under Marshal Ney. But their effectiveness would be compromised by hasty deployment and a critical absence of support.

And then there was the crown jewel: the Imperial Guard. This elite corps, divided into Old, Middle, and Young Guards, was Napoleon’s personal sledgehammer. The Old Guard, grizzled and unshakable, had never broken in battle. Their very presence on a field often turned the tide. Napoleon kept them in reserve until the decisive moment. When the Guard moved, the army followed. At Waterloo, they would march again. But for the first time in history, they would not return victorious.

Facing them on the opposite ridge was a very different force. The Duke of Wellington commanded approximately 68,000 men drawn from across Europe. Only 24,000 were British regulars. Another 6,000 came from the King’s German Legion, experienced and well-disciplined troops. The rest were Dutch, Belgians, Hanoverians, Brunswickers, and Nassauers. Some had never fired a shot in anger. Others had fought for Napoleon just a year earlier. Holding this diverse force together required more than strategy. It required iron will, and Wellington had plenty of that.

Wellington’s men were positioned behind the ridge at Mont-Saint-Jean, where hedgerows and undulations shielded them from direct artillery fire. His artillery corps numbered 156 guns, not as many as Napoleon’s, but used with deadly efficiency. Wellington didn’t waste powder. He waited until the enemy was close, then unleashed hell.

British infantry were drilled to fight in line, two ranks deep, maximizing their firepower. They could deliver disciplined volleys with brutal speed and precision. Wellington had long understood that firepower, not flash, wins battles. His cavalry included heavy dragoons and light hussars. The famed Union Brigade, made up of the Royal Dragoons, Inniskillings, and Scots Greys, would smash into the French center in one of the most iconic charges of the Napoleonic Wars, though their enthusiasm would carry them too far and cost them dearly.

The real test for Wellington wasn’t numbers or guns. It was cohesion. With five languages spoken among his troops and uneven levels of experience, coordination was a nightmare. But Wellington made it work. He placed the most reliable units where the line was weakest, and he trusted the ground to do the rest. He didn’t need to destroy Napoleon’s army. He just needed to hold the ridge until Blücher arrived.

And that brings us to the Prussians. Nearly 50,000 strong under Field Marshal Gebhard Leberecht von Blücher, they were battered but unbroken from their loss at Ligny two days earlier. Blücher himself had been injured, pinned beneath a dead horse. But nothing short of death was going to keep him from this fight. His subordinate, General Gneisenau, skillfully reorganized the army and directed its march toward Wellington.

Blücher’s Prussians were the hammer that would strike Napoleon’s right flank. Though they would arrive late in the day, they would arrive in force. Their numbers included infantry, cavalry, and a solid artillery train. While not as disciplined as Wellington’s British, they brought raw determination and sheer numbers. Blücher had made a promise: he would be there, no matter what. And as the French tide began to crest, the black-clad soldiers of Prussia emerged from the woods to fulfill that vow.

Three armies. Three different structures. Three different philosophies. Napoleon, relying on speed and precision, counting on his veterans and the fear he once inspired. Wellington, calm and calculating, putting faith in discipline, positioning, and stubborn defense. Blücher, all heart and grit, gambling everything on his men’s willingness to push through fatigue and arrive in time.

At Waterloo, it was never just about numbers. It was about nerve. It was about experience, trust, and the will to stand when the line begins to bend. Napoleon had the power. Wellington had the position. Blücher had the promise. And when those three forces finally collided in the mud and smoke of that June day, the world would change.

The Battle of Waterloo began not with a roar, but with a long, muddy wait. The morning of June 18, 1815, was damp and sullen, the aftermath of a thunderous downpour that had turned the rolling farmland south of Brussels into a sodden quagmire. Napoleon Bonaparte, perched on the ridge near La Belle Alliance, surveyed the field with a calculating eye and made the first fateful decision of the day: he would wait. The ground was too wet. His heavy artillery, the pride of the French army, couldn’t be moved into effective firing positions without bogging down. The battle would not start at dawn, but later. That delay, measured in hours, would haunt him by nightfall.

The battle of Waterloo was won on the playing fields of Eton.

Duke of Wellington

When the French guns finally did open up, around 11:30 in the morning, the battlefield erupted. The first major thrust was directed at the château of Hougoumont on the Allied right. What had begun as a diversionary assault turned into a brutal, day-long struggle. Prince Jérôme Bonaparte, Napoleon’s younger brother, led wave after wave of French troops against the walled farmhouse, hoping to draw in Wellington’s reserves. But the British Guards stationed there, Coldstream and Scots, refused to budge. The gates were barred, loopholes cut in the walls, and every inch of ground turned into a killing zone. The French fought with grim determination, breaching the orchard, setting fire to buildings, even forcing their way into the courtyard. At one point, the main gates were smashed open and French infantry surged in. But a heroic counterattack by a handful of defenders slammed them shut again, trapping the enemy inside. Few escaped.

Though technically a sideshow, Hougoumont became a vortex that consumed thousands of French troops. Napoleon had not intended to win the battle there, but the tenacity of both attackers and defenders made it one of the most critical and symbolic fights of the day.

By early afternoon, attention shifted to the Allied center and left. Marshal Ney, commanding the French left wing, ordered General d’Erlon’s corps, some 18,000 men, into a massive column attack against Wellington’s line near La Haye Sainte, a sturdy farmhouse that anchored the British center. The French marched across the valley in formation, expecting to roll over the defenders. But Wellington had hidden his troops just behind the ridge. When the French reached the crest, the British rose as one and fired a devastating volley at close range. The front ranks fell like wheat. British cavalry charged down from the ridge, Scots Greys, Royal Dragoons, and Inniskilling Dragoons, crashing into the stunned French and capturing several guns.

But success turned to disaster. The British cavalry, in their zeal, charged too far, lost cohesion, and were counterattacked by French lancers and cuirassiers. The Union Brigade was effectively destroyed as a fighting force. Still, the center held, and La Haye Sainte remained in Allied hands, for the moment.

Then came one of the strangest and most infamous decisions of the day. Around 3 p.m., Ney, misreading signs of British redeployment as a retreat, launched an all-out cavalry assault against the ridge. Without infantry or artillery support, he sent wave after wave of French horsemen, thousands in total, up the slope toward the British lines. Wellington’s infantry, drilled to perfection, responded with textbook precision. Forming defensive squares, they stood like iron boxes, bristling with bayonets and pouring musket fire into the swirling cavalry. Again and again, Ney attacked. And again and again, he was thrown back. French losses were staggering. Horses collapsed in heaps. Riders fell, only to be trampled by the next wave. Still, the squares held. The assault, brave to the point of madness, had failed to break the line and had squandered much of Napoleon’s cavalry.

As the French tried to regroup, thunder rose from the east. The Prussians had arrived.

Around 4:30 p.m., the leading elements of Field Marshal Blücher’s army, General Bülow’s corps, began attacking the French right flank near the village of Plancenoit. Napoleon had hoped Grouchy would pin the Prussians at Wavre, but Grouchy was still miles away. Instead, Napoleon had to divert precious reserves, including the Young Guard, to hold the town. What followed was bitter street fighting. Plancenoit changed hands multiple times, burned, and bled, but the Prussians kept coming.

Now Napoleon was fighting on two fronts, Wellington to the north, Blücher to the east, and the strain was showing. His central infantry attacks had stalled. Ney’s cavalry was shattered. Artillery ammunition was dwindling. La Haye Sainte finally fell around 6 p.m., giving the French a brief foothold in the center. But Wellington, sensing the danger, poured in reinforcements. The line bent, but did not break.

Napoleon had one last hope. The Imperial Guard.

As dusk approached, the Emperor played his final card. He formed a column of the Middle and Old Guard, his most elite troops, veterans of Austerlitz, Eylau, and Wagram, and sent them up the slope toward the Allied center. Drums beat. Bearskin shakos swayed. The Guard marched in silence, a wall of steel and discipline.

For a moment, time froze. On the ridge, British Guardsmen lay hidden behind the crest. As the French Guard reached the top, the British stood and fired a crashing volley. Then another. Then a charge. The Guard faltered. Then, shockingly, it retreated.

A cry swept through the French lines: “La Garde recule!” The Guard is retreating.

That moment shattered the illusion of invincibility. Panic rippled through the French ranks. Units broke and ran. Some tried to rally around Napoleon, but it was too late. Wellington, seeing the collapse, rose from his command post and waved his hat, his signal for a general advance. The Allied line surged forward. On the French right, the Prussians broke through. It became a rout.

The French army disintegrated into chaos. Soldiers threw down muskets and ran. Officers tried to rally them, only to be swept away in the flood. Napoleon, stunned, tried to form a rear guard but realized the battle was lost. He fled the field, his last hope crushed under the weight of mud, steel, and relentless Allied resolve.

By nightfall, it was over. The battlefield was a charnel house. Over 40,000 men lay dead or wounded. But the era of Napoleon, the man who had once ruled from Lisbon to Moscow, was finally, irrevocably, finished.

Waterloo was not just a military defeat. It was a spiritual one. The Guard had retreated. The myth had shattered. Europe exhaled again, but this time, for good. Napoleon’s star had fallen, not in fire, but in mud, blood, and silence.

“Next to a battle lost, the saddest thing is a battle won.”

Arthur Wellesley, Duke of Wellington

The battlefield at Waterloo was silent by nightfall, but the silence did not bring peace. It brought the stink of death, the groans of the wounded, the crackle of smoldering barns, and the slow, heavy knowledge that everything had changed. Napoleon Bonaparte, once the scourge of kings, the master of Europe, the man who had redrawn maps with cannonballs, was now a fugitive.

He did not linger. As the wreckage of his army scattered southward in chaos, Napoleon rode hard for Paris. He knew what had happened. He knew what it meant. The Guard had broken. The Allies had held. The game was up.

On June 21, just three days after the disaster, Napoleon arrived in the capital and tried to rally support. But the spell was broken. The Chamber of Deputies refused to back him. His old allies were silent or already fleeing. The press, once censored under his iron hand, now whispered the words he had long feared: defeat, abdication, surrender. On June 22, Napoleon abdicated the throne for the second time. This time, he would not return.

He briefly toyed with escape to the United States. He even made his way to the port of Rochefort, hoping to board a ship before the British blockade tightened. But it was too late. On July 15, he surrendered to the captain of HMS Bellerophon and was taken into British custody. No theatrics. No grand farewell. No Austerlitz speeches. Just the end of the road.

The British knew better than to exile him somewhere as close and escapable as Elba. This time, they chose St. Helena, a lonely volcanic rock in the South Atlantic, a thousand miles from anything resembling civilization. It was a prison without bars, guarded by sea and distance. Napoleon would never set foot on European soil again. He died there in 1821, a shadow of himself, surrounded by a handful of loyalists and the ghosts of his own ambition.

Waterloo was a bloodbath. Roughly 25,000 French were killed, wounded, or missing. The Allies and Prussians suffered nearly 22,000 casualties. The fields south of Brussels ran red, the ditches choked with bodies, the air thick with the stench of powder and decay. Eyewitnesses would speak of horses piled atop one another, men buried where they fell, and entire units that simply vanished into the mud. It was one of the most brutal single-day slaughters in European history up to that point.

But the political shockwave went even further.

The Bourbon monarchy was restored once again. Louis XVIII returned to Paris behind Allied bayonets, pale and sweating, as the streets gave a half-hearted cheer. The French people were exhausted. They didn’t care much who wore the crown, so long as the wars stopped. And they did. For a time.

The Congress of Vienna, which had convened in 1814 to redraw the map of Europe, was vindicated. Its critics had called it reactionary, naive, a bundle of outdated monarchs clinging to the past. But Waterloo proved that unity among the great powers could contain even the most aggressive challenger. The balance of power held.

British prestige soared. Wellington, already admired, became a legend overnight. Britain emerged from the Napoleonic Wars as the preeminent global power, naval, financial, and now military. The Royal Army, long seen as second-rate compared to France’s continental juggernaut, had stood its ground and helped bring the Empire down.

For Prussia, too, Waterloo was a moment of arrival. Blücher’s role in the victory, his tenacity, his dogged march to the battlefield, his army’s decisive intervention, cemented Prussia’s reputation as a rising military power. It would take another fifty years and another war against France, but the seeds of German unification were watered in the blood of that day.

And France? France would never again dominate the European continent as it had under Napoleon. Its armies, once the gold standard of military excellence, now bore the mark of defeat. For the rest of the 19th century, France would play catch-up, rebuilding prestige, reinventing itself politically over and over again. The sun had set on its imperial century.

Yet even in defeat, Napoleon’s legacy endured. He had shattered the old world and remade it in his image. The Napoleonic Code, his administrative reforms, his concept of meritocracy, all survived. His military innovations became doctrine in every European army. And while kings ruled again, they did so with the uneasy awareness that the people had once followed a Corsican soldier to the gates of Moscow.

Waterloo was the end of an era. The end of imperial dreams. The end of a man who had once dared to crown himself. The battlefield was quiet now. But the world would never be the same.

The guns had barely cooled at Waterloo when the contest for its memory began. If the battle was about power on the field, its legacy became a struggle for narrative. Who won Waterloo? That depends on whom you ask, and when.

In Britain, the answer came quickly and loudly. The Duke of Wellington, already a national figure after years of hard campaigning in the Peninsular War, was elevated to near-mythic status. He was hailed as the savior of Europe, the man who stopped Napoleon with little more than grit, guile, and a good pair of boots. His statue would soon loom over cities. Streets would bear his name. British schoolboys would memorize the line he uttered to describe the battle: “The nearest run thing you ever saw in your life.” It was a masterstroke of understatement. A brush with catastrophe, turned into triumph.

Wellington was, indeed, a brilliant commander, but the British press, and the public, eagerly reshaped the story. The narrative cast Waterloo as a glorious solo act. The multinational composition of his army, the Dutch, Belgians, Nassauers, Brunswickers, and Germans, was often brushed aside or minimized. So too was the critical role of the Prussians. In the telling of the Times and the tea houses, it was Wellington’s day.

The Prussians saw it differently.

To them, Waterloo was a joint effort, and a near disaster averted by sheer Prussian resolve. After being beaten at Ligny just two days earlier, Blücher and his men could have retreated east and left Wellington to face Napoleon alone. But they didn’t. Wounded and nearly crushed, Blücher kept his word. He marched his battered army through the night, navigating muddy roads and chaotic terrain, to strike Napoleon’s right flank late in the afternoon. It was this move, at a moment when Wellington’s line was stretched to its limits, that tipped the balance.

Blücher’s name is less well-known in the Anglophone world, but in Prussian memory, he was the old warhorse who delivered the final blow. His army’s arrival was no sideshow. It was the hammer to Wellington’s anvil. Without it, Napoleon might very well have won. In German military tradition, Waterloo was not a British victory with Prussian help, it was a coalition triumph led by two equals.

And the French? For them, Waterloo was not just a defeat. It was a wound that festered.

To many in France, the loss was not Napoleon’s fault. It was bad luck. Treachery. Divine punishment. A storm that softened the ground, a general who failed to act, a cavalry charge launched too soon. Grouchy’s failure to intercept the Prussians became a national obsession. Ney’s impulsiveness was blamed. Even fate was blamed.

In some circles, Napoleon was martyred. A hero betrayed by lesser men and crushed by the weight of jealous monarchs. The Revolution’s brightest flame snuffed out not by superior tactics, but by conspiracy and chance. This idea would become a rallying cry for future Bonapartists, and a deep undercurrent in French politics throughout the 19th century. Waterloo was never just about what happened, it was about what might have been.

The legend only grew with time.

Victor Hugo would write about Waterloo with almost religious reverence in Les Misérables, calling it a “gory masterpiece.” In his telling, it was an act of God, a moment where human destiny was rewritten in fire and mud. Thackeray, in Vanity Fair, placed his characters at the margins of the battle, cementing its place in the English literary imagination as a moment of chaos, fate, and character revealed. The field itself became a place of pilgrimage. Tourists came, wept, and pointed at the Lion’s Mound.

Even pop culture joined the fray. Over a century and a half later, the Swedish band ABBA resurrected the name with their 1974 Eurovision hit Waterloo, likening romantic surrender to the emperor’s downfall. That one word, Waterloo, had become shorthand for defeat, for inevitability, for the moment when resistance collapses and history marches on.

In military academies, Waterloo became a case study. In classrooms, a turning point. For conservatives, it was the restoration of order. For liberals, a tragic end to a daring dream. For monarchists, vindication. For republicans, a cautionary tale. Each nation, each ideology, found its own meaning in that muddy Belgian field.

And what of the men who fought there?

Many of them died without knowing who had truly “won.” For them, there were no grand narratives. Just the blast of a musket, the clang of a saber, the sudden jolt of a bullet or a shell. They lay in ditches and farmhouses, in hedgerows and courtyards, young and old, French and British, German and Belgian. They weren’t chasing myth. They were trying to survive.

The myth of Waterloo would be shaped by historians, poets, generals, and politicians. The truth of Waterloo, confused, contested, and covered in blood, was buried with the dead.

So, who won?

Wellington would say it was the closest thing to a loss he ever saw. Blücher would say he came just in time to save Europe. Napoleon, from his prison on St. Helena, would brood over what went wrong and how history would judge him.

In the end, perhaps the answer lies not in flags or monuments, but in the sobering silence that follows every great clash of ambition and fate. Waterloo was a victory, yes, but it was also an ending. Of an empire. Of a dream. Of an age.

The rest is memory. And memory, like the battle itself, belongs to whoever tells it loudest.

War is made by emperors, but remembered by soldiers. And at Waterloo, behind the numbers and maps and myths, were the lives, beating, bleeding, and breaking, of the men and boys who fought in that muddy Belgian crucible on June 18, 1815.

“A soldier will fight long and hard for a bit of colored ribbon.”

Napoleon

Imagine standing in the center of a British infantry square. Around you are your mates, shoulder to shoulder, bayonets out like a hedgehog’s quills. There are drums in your ears, musket fire ahead, and the ground trembling beneath your boots as thousands of French cavalry charge directly at you. It’s a wall of hooves and steel and shouted orders, all aiming to break your will. But you don’t break. You hold. Because if the square cracks, you all die.

Private James Anton of the 42nd Highlanders remembered the scene vividly. His regiment stood on a rise, ordered into square as Marshal Ney hurled wave after wave of cuirassiers at them. “Their shining breastplates and helmets glittered in the sun,” he wrote. “They looked like demons.” The horses galloped straight at them, but the square held, unmoved and unbroken. The cavalry swirled around, unable to penetrate. It was discipline, drilled into the bones, that saved them.

Then there was the Imperial Guard, the elite of the elite, who stood their ground when most of the French army was already in flight. These were Napoleon’s chosen men, veterans of Austerlitz and Jena, men who had survived the snows of Russia and the blood of Spain. As the sun dipped toward the horizon and the Prussians poured in from the east, Napoleon ordered the Guard to advance up the ridge.

They marched without music, without shouting. Just the sound of boots in mud. Stoic. Stern. When they reached the crest, British Guards hidden behind the slope stood and fired. A volley. Then another. The Guard faltered. Some fell. Some held. But eventually, for the first time in their history, they broke.

It was not a rout. It was a retreat, dignified even in defeat. According to accounts, when a British officer called on a wounded French Guard to surrender, the reply came firm and final: “La Garde meurt, elle ne se rend pas.” The Guard dies, it does not surrender. Whether truly spoken or mythologized after the fact, it captured the moment. These men had given all they could. And still, it was not enough.

Among the wreckage of great armies were smaller stories, quieter, but no less human. Surgeon James Guthrie of the British Army was overwhelmed by the carnage. For hours after the guns fell silent, he worked by lamplight, amputating limbs, sewing wounds, listening to the final murmurs of men too far gone to save. One account tells of Guthrie performing nearly 200 amputations in 24 hours. He did not sleep. He barely spoke. He just cut and bandaged and prayed that some of them might live.

Civilians, too, were caught in the storm. Belgian peasants fled their farms, leaving livestock and tools behind. Others huddled in cellars as shells tore through their barns and homes. After the battle, many wandered back across fields of corpses to find their lives scattered among the ruins. Some became unwilling caretakers, burying soldiers where they fell, or helping wounded men crawl toward aid.

One Dutch soldier, a teenager named Hendrik Klooster, was shot through the leg and left on the field. He later recounted hearing voices in the dark, French and British, wounded and dying, calling out for water, for mothers, for God. He dragged himself toward a farm wall and passed out. He awoke days later in a field hospital, surrounded by groaning, limbless shapes, and the smell of decay.

War does not spare the soul. It doesn’t choose its victims for their valor or villainy. At Waterloo, bravery and agony marched hand in hand. Some lived to tell their stories. Many did not. Their letters are gone, their names forgotten. But they were there, in the smoke and mud and terror. Not just as pawns in a general’s plan, but as sons, fathers, and friends, each with a moment when they held the line or ran for cover, when they prayed or cursed or simply closed their eyes and hoped it would end.

The Battle of Waterloo decided the fate of empires. But for those who stood in the squares, charged with sabers, patched wounds with torn shirts, or wept in burning farmhouses, it was something else. It was survival. It was sacrifice. It was the human cost of history.

As the smoke lifted over Waterloo, the last roar of the Corsican Lion faded into history. Napoleon Bonaparte, once master of Europe, had been undone not by one single enemy, but by the weight of time, the weariness of nations, and the limitations of genius. He was brilliant, yes, a strategist of unmatched creativity, a reformer who reshaped institutions, a man whose rise from obscurity had electrified an age. But he was also blinded by the myth he helped craft, shackled by his own legend. His return from Elba had seemed like a miracle. But miracles, it turns out, have their limits.

At Waterloo, ambition met resistance. Not just the resistance of Wellington’s cold discipline or Blücher’s stubborn persistence, but the resistance of a continent grown tired of war. Tired of being redrawn, conscripted, taxed, and shattered to fuel the glory of one man’s will. Napoleon’s downfall wasn’t merely a military defeat. It was a reckoning. The world was no longer his to command.

The battle offers no easy morals. It was not good triumphing over evil. It was armies grinding into one another, allies barely trusting each other, commanders gambling with the lives of tens of thousands. And yet, through that carnage, a lesson persists: empires built on ambition alone cannot last. No matter how brilliant the leader, no matter how loyal the troops, the weight of the world eventually becomes too much for one man to bear.

Waterloo teaches the power of alliance. Wellington’s line alone could not have held forever. Blücher’s Prussians turned the tide. Two commanders, two very different men, united by necessity and resolve, succeeded where a single emperor failed. In a world of complex threats, it is often cooperation, not charisma, that wins the day.

And it teaches about overreach. Napoleon had once held the crown of nearly all Europe. But like so many before him, he pushed too far, too fast. In the end, it wasn’t just the ground beneath his feet that gave way. It was the ground beneath his ideas.

The map of Europe was never the same again. Lines were redrawn, kings restored, republics repressed or reimagined. But in that quiet after the thunder, with the smoke drifting over blood-soaked ridges and shattered limbs, something else lingered, a silence that comes when history exhales.

Napoleon’s roar had echoed across the continent. At Waterloo, it ended with a whisper.

Leave a comment