Boston in June of 1775 was already a city choking on powder smoke, rumor, and fear. Since the redcoats had marched out to Concord two months earlier and came running back under fire, everything had changed. The countryside had risen. Thousands of armed men now surrounded the city. The roads were blocked. Tempers were short. British soldiers camped uncomfortably close to colonists who hated their presence. Governor General Thomas Gage, once seen as a somewhat moderate military administrator, now found himself barricaded in Boston, his authority mocked by the very people he had come to govern. And on June 12, 1775, he played his last card.

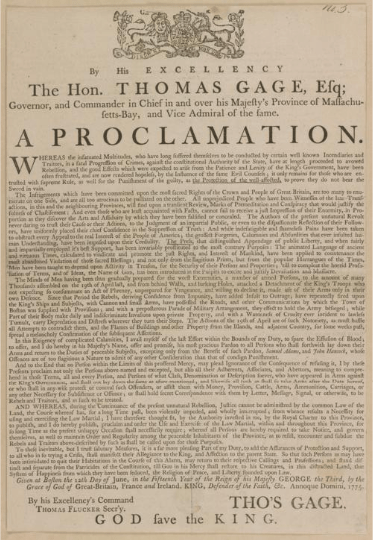

That morning, Gage issued a proclamation from the seat of royal power, declaring that the colony of Massachusetts was in a state of open rebellion. He went further. He imposed martial law. This was not merely a crackdown. It was a formal declaration that military rule would replace civilian governance. From that moment, the rule of law would be delivered from the end of a musket.

The proclamation wasn’t just a bureaucratic statement. It was dramatic. Gage offered pardons to those willing to lay down arms and return to loyalty, but with two thunderclap exceptions. Samuel Adams and John Hancock, two of the most prominent leaders of the resistance, were declared unworthy of forgiveness. The gloves were off. The British Crown was no longer pretending this was anything but war.

To understand why Gage would take such a drastic step, you have to rewind the clock a bit. The previous year had seen the passage of the so-called Intolerable Acts in Parliament, punishing Boston for the Tea Party and tightening royal control across Massachusetts. Gage, who wore both a military uniform and the robes of the governor, was sent to enforce this new order. He dissolved the Massachusetts assembly. He shut down town meetings. He sent British troops to seize colonial gunpowder and arms. But each time he acted, the opposition grew more defiant.

The last straw came on April 19, when Gage dispatched troops to seize colonial supplies in Concord. The famous midnight ride of Paul Revere wasn’t just for show. The colonists knew the British were coming. The confrontations at Lexington and Concord saw blood spilled, and when the redcoats retreated, they were harried and hunted all the way back to Boston by an angry militia. That wasn’t just a skirmish. That was the start of a siege.

So by the time Gage issued his martial law decree, he was a man cornered. His hope was that the proclamation would shock the rebels into submission. He believed that if he offered clemency, the rank-and-file colonists might separate themselves from the so-called rabble-rousers and come back into the fold. Maybe if he named names and held up Adams and Hancock as the real villains, the rest would abandon the cause.

But that hope was badly misjudged. The people of Massachusetts were not trembling in fear. They were simmering with resolve. To many colonists, the declaration of martial law was proof that the Crown had no intention of respecting their rights as Englishmen. The message was clear: your government is now your enemy.

The tone of the proclamation was meant to sound firm but fair. In reality, it came off as hollow and threatening. It talked about restoring peace, but peace at gunpoint is not peace. Gage expected to scare the rebels into obedience. Instead, he hardened their resolve.

The Sons of Liberty were not about to sit quietly while Gage declared war on their movement. They had been organizing, publishing, whispering, and planning for over a decade. Samuel Adams was the master strategist of rebellion. He knew how to inflame public opinion without lighting the match himself. Hancock, wealthy and well-connected, put his purse and name behind the cause. Others like Revere rode out with news and warnings, building the colonial information network that kept everyone a step ahead of British moves.

Gage’s declaration didn’t break that network. It supercharged it. Within days, patriot printers were circulating the full text of the proclamation along with scathing rebuttals. Pamphlets appeared denouncing Gage as a tyrant and accusing him of turning Boston into a military prison. Town meetings and committees across the colony reaffirmed their loyalty to their cause, not the Crown. And the names Adams and Hancock, far from being shamed, became even more revered.

The Liberty Tree, that gnarled old elm in Boston that had stood as a silent witness to years of protest and planning, became a symbol once again. Gage’s words hadn’t killed the resistance. They had fertilized it.

Just four days later, the colonists responded not with surrender, but with gunpowder. On the night of June 16, colonial militia under orders from Colonel William Prescott occupied Breed’s Hill overlooking Boston Harbor. Gage responded by launching a full assault the next day. What followed was the bloody Battle of Bunker Hill. The British won the hill but lost over a thousand men in the process. Gage had won a patch of dirt, but he lost the moral high ground and, eventually, his command. He would soon be recalled to England, his authority in tatters.

The proclamation of June 12, 1775, was supposed to restore British control. It did the opposite. It confirmed what many already suspected, that reconciliation was no longer an option. The Crown had moved from politics to punishment. From negotiation to military force.

But the colonists had already chosen their path. The offer of pardon was too little, too late. The punishment of Adams and Hancock only made them heroes. The martial law decree intended to crush rebellion instead gave it a rallying cry.

Looking back, it’s clear that General Gage misunderstood the soul of the people he was sent to govern. He believed order could be restored by force, that a public gesture of forgiveness would divide the resistance, and that martial law would cow a restless population into silence. He was wrong on every count.

The people of Massachusetts were not merely subjects of the Crown. They were citizens of a cause. And that cause could not be undone by proclamations nailed to posts or redcoats marching through muddy streets. In trying to impose order, Gage helped light the fire that would burn through the empire.

June 12, 1775, wasn’t the day Boston broke. It was the day Boston stood tall and told the Crown: We are not afraid of your laws, your proclamations, or your king.

Leave a comment