In a world filled with flashy scientific breakthroughs and high-tech wonders, it is easy to overlook the small, humble tools that made it all possible. The Petri dish is one of those quiet heroes. It does not beep, buzz, or require a power source. It just sits there, a shallow glass or plastic dish with a clear lid, providing the perfect stage for one of nature’s most remarkable dramas: the growth and study of microscopic life.

The story of the Petri dish begins in nineteenth-century Germany, in a time when modern science was beginning to take shape. This was an era when men like Louis Pasteur and Joseph Lister were revealing the hidden world of germs and transforming medicine. Among them was Robert Koch, the father of modern bacteriology. Koch and his assistants were pioneering the use of solid culture media to grow and study bacteria, but their methods were awkward and prone to contamination. Glass slides were placed under large bell jars, and while bacteria could grow, the process was clumsy and unpredictable.

Enter Julius Richard Petri. Born May 31, 1852 in Barmen, Prussia, Petri was the son and grandson of respected academics. He studied medicine and served as a military physician before landing at the Imperial Health Office in Berlin, where he became Koch’s assistant. While working alongside Koch, Petri saw the problems firsthand. He recognized that growing bacteria on a solid surface was the right idea, but the setup needed refinement. It was Petri who proposed replacing the oversized bell jar with a simple, flat glass lid slightly larger than the dish itself. This new design allowed scientists to keep their cultures sealed but visible. The result was easier handling, less contamination, and a clearer view of bacterial colonies. The Petri dish was born.

It was not a revolutionary leap, but rather an elegant refinement. That is often how progress works in science. Someone spots a weak point and finds a better way. In 1887, Petri published a short paper describing his modification to Koch’s technique. The dish quickly became the standard, spreading through laboratories across Europe and beyond. Some have argued that other scientists, including Victor Babes and Victor Cornil, described similar dishes before Petri. But it was Petri’s version that caught on, because it worked. It was simple, efficient, and easy to reproduce.

Petri’s career continued after he left Koch’s lab. He directed a tuberculosis sanatorium and later the Museum of Hygiene in Berlin. He published nearly 150 papers, many of them on hygiene and bacteriology. He was known for his strict discipline, his academic rigor, and his deep commitment to public health. He passed away in 1921, but his name lives on every time a scientist picks up a Petri dish.

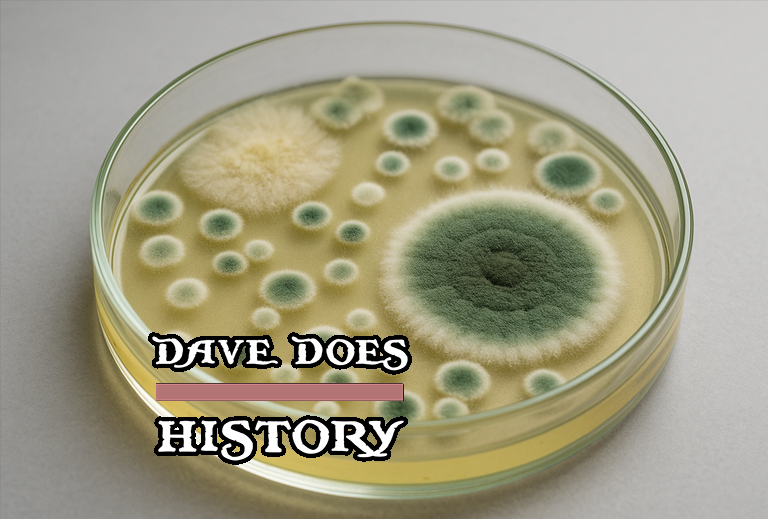

Over the past century, that unassuming dish has been at the center of some of science’s most important moments. In 1929, Alexander Fleming famously discovered penicillin when he noticed that a mold contaminating one of his Petri dishes had killed nearby bacteria. Petri dishes have helped scientists identify the bacteria behind tuberculosis, typhoid, diphtheria, and cholera. They have played a role in testing vaccines, developing antibiotics, and understanding the spread of disease.

But the Petri dish is not just a medical tool. It is a symbol. It stands for curiosity, for experimentation, and for the idea that even the smallest container can hold the key to a global breakthrough. In classrooms, it introduces students to the invisible world of microbiology. In labs, it helps researchers test new drugs. In popular culture, it represents the process of controlled experimentation. People speak of a city or an idea as a “Petri dish” when describing environments that breed new things, whether good or bad.

Even today, in an age of high-tech gene sequencers and robotic lab assistants, the Petri dish holds its ground. It has evolved in small ways. Modern dishes are often made of disposable plastic. Some come with grids or built-in sensors. Scientists are now using them to grow replacement organs or to analyze microbial behavior in ways Petri himself could never have imagined. Yet the core idea remains the same. A flat surface, a nutrient gel, and the chance for life to grow.

The beauty of the Petri dish is that it combines function with clarity. It does not need batteries or programming. It only needs patience, observation, and a little bit of skill. In that way, it is a reminder that not all progress needs to be loud or complicated. Sometimes the most powerful innovations are the simplest ones. Julius Richard Petri did not invent the wheel, but he made it roll a little smoother. And for that, the world owes him a quiet, lasting thank you.

Leave a comment