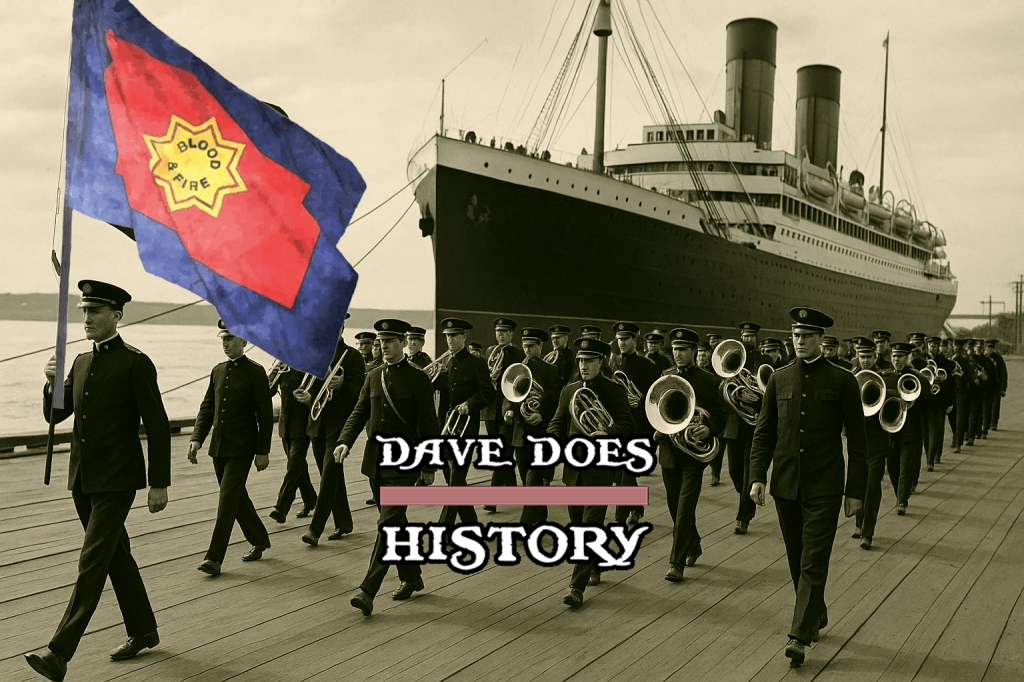

They marched through the heart of Toronto with music in their step and joy in their hearts. It was May of 1914, and for the members of The Salvation Army’s Canadian delegation, the year had been proclaimed a banner one. They were heading to the third International Congress of The Salvation Army in London, England. There was purpose in their journey, pride in their uniforms, and a kind of innocent excitement that only comes when faith and fellowship cross an ocean together.

A brass band played triumphantly as the delegation paraded down Yonge Street, flags unfurled and hopes high. Spectators lined the street, waving handkerchiefs, tipping hats, and calling out encouragement. For many in the crowd, these men and women represented the best of Canada’s young spiritual movement. Among them were leaders, musicians, secretaries, and even entire families. The Canadian Staff Band led the way, a force of musical excellence and spiritual discipline. Their destination was Quebec City, where they would board the RMS Empress of Ireland, a stately liner that had earned a reputation as reliable, fast, and thoroughly modern.

The ship herself had carried more than a hundred thousand immigrants across the Atlantic. She was no Titanic, at least not in terms of glamour or myth, but she was beloved. Built by the Canadian Pacific Railway to link its steamship and rail operations, the Empress of Ireland had completed ninety-five successful crossings by the spring of 1914. She boasted lifeboats for more than 2,000 people, a number that provided comfort to passengers still haunted by the iceberg tragedy of two years earlier. Captain Henry Kendall, in command of his first voyage aboard the Empress, assured passengers of the vessel’s safety. Lifeboat drills were conducted. Confidence was high.

It had been a long train ride from Toronto to Quebec, but spirits remained buoyant. For the Salvationists, this was more than a voyage. It was a pilgrimage. Commissioner David Rees, the Canadian territorial commander, was on board. So was Colonel Maidment, the chief secretary. Adjutant Edward Hanagan, bandmaster of the Canadian Staff Band, was traveling with his musicians, many of whom were young men full of promise. There was Brigadier Henry Walker, editor of The War Cry, the Army’s publication, along with his wife and other members of the headquarters staff. One hundred sixty-one members of the Salvation Army family were among the passengers. They represented not only the soul of the movement in Canada but also its future.

The ship pulled away from Quebec City on the afternoon of May 28. The St. Lawrence River lay calm under a dusky sky. There was a final mail stop at Rimouski and then at Pointe-au-Père, where the river pilot disembarked. After that, it was full steam ahead for Liverpool. By all accounts, the first evening aboard was uneventful. Passengers enjoyed dinner, strolled the decks, and retired for the night. For the Salvationists, it was a quiet night of rest after days of travel and preparation.

In the early hours of May 29, the fog rolled in, thick and sudden. It was not just any fog. It was the kind of spring fog peculiar to the St. Lawrence, born from the clash of warm air and cold river water. Visibility dropped to nothing. Somewhere in the murk, another ship, the SS Storstad, a Norwegian collier loaded with coal, was steaming upriver. Both vessels saw each other before the fog enveloped them. Signals were exchanged. Engines were reversed. Then, silence.

At 1:55 in the morning, the Storstad emerged from the fog and struck the Empress of Ireland broadside. The blow was not violent in sound. Survivors described it as a bump more than a crash. But the impact tore a gaping hole into the starboard side of the Empress. Water poured in with unimaginable force. Crew scrambled to close watertight doors, but there was no time. Within minutes, the liner began to list. Lifeboats could not be lowered on the port side. Panic set in. Only five or six boats made it into the water safely. Most passengers never made it out of their cabins.

In just fourteen minutes, the Empress of Ireland rolled onto her side and disappeared beneath the surface. The lights had gone out within minutes. The ship’s power failed early. Screams filled the darkness. Cold water choked the decks. People clawed their way through corridors, some still in nightclothes, others barely awake enough to comprehend what had happened. The lucky ones reached the deck or found something to cling to. Most did not.

Of the 1,477 people on board, only 465 survived. Among the dead were 133 members of The Salvation Army. Of the Canadian Staff Band’s forty-one members, only twelve lived. The rest, including Adjutant Hanagan, perished. Commissioner Rees and Colonel Maidment were lost, along with their wives. Brigadier Walker died. Entire family units vanished beneath the waves. One survivor, seven-year-old Grace Hanagan, would live into the 1990s as the last known survivor of the disaster. She lost both her parents that night. Her story became emblematic of the many Salvationist children who went to sea full of hope and were orphaned before dawn.

The loss hit hard across Canada. Early reports claimed all had been saved. Cheers rang out as Salvation Army headquarters in Toronto posted the first telegrams. But as the hours passed and details emerged, hope gave way to despair. Bodies began arriving at Rimouski and were transferred to Quebec City for identification. Pier 27 was turned into a makeshift mortuary. The Canadian Pacific Railway worked quickly to support grieving families, but no compensation could restore what had been lost.

At The Salvation Army’s territorial headquarters, officers stood in stunned silence as casualty lists grew. Names were read aloud. Notices were posted on the windows. It was not just a tragedy. It was a devastation. The loss of leadership, musicianship, editorial talent, and spiritual vision all at once dealt a blow from which the Army in Canada would take years to recover.

And yet, the movement did not falter. It regrouped. It mourned. It remembered. The survivors carried the banner forward, telling stories of sacrifice and courage. In their memory, the Army grew stronger. The Canadian Staff Band was reconstituted. New officers rose. New voices filled pulpits and platforms where old ones had been silenced.

Today, the story of the Empress of Ireland is still often overshadowed by the more famous tales of the Titanic and the Lusitania. But for The Salvation Army, this tragedy remains deeply personal. It is woven into the soul of the organization. Memorials exist not only at Pointe-au-Père and Rimouski, but also in small towns, churches, and Salvation Army halls across Canada.

From time to time, the story resurfaces in band concerts, remembrance services, and museum exhibits. At the Old Mill Heritage Centre on Manitoulin Island, an annual history day recalls the loss. Salvationists gather to play the old hymns, to speak the names, to honor the martyrs. The message is simple: they have not been forgotten.

In the end, those 133 Salvationists did not die as tourists. They died as missionaries, bound for a great convocation, committed to a gospel that asks for everything. They died not only with honor, but in the very act of service. Their voyage, though cut short, was a continuation of their ministry. And in that, their story lives on.

No monument or brass plaque can fully capture the sorrow and courage of that night. But every time a Salvation Army band plays, every time a War Cry is printed, and every time a young Salvationist marches in faith, the legacy of the Empress of Ireland sails again, unbroken by time, unshaken by the cold waters of history.

Full Disclosure: I grew up in The Salvation Army. My father (of blessed memory) was a musician and it was from him that I first heard the story of the Canadian Staff Band and the Empress of Ireland. I learned to play musical instruments, and on occasion we would honor the memory of the Canadian Staff Band with particular selections of music.

Later, I would get to interview author Clive Cussler, and we had an amazing off-air conversation about his book “Night Probe,” which deals with the Empress sinking and the connection to The Salvation Army.

Leave a comment