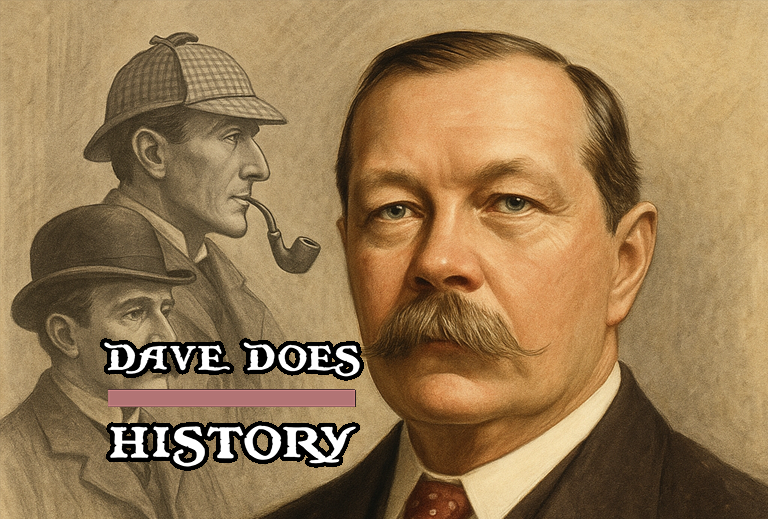

How can a man who created the hyper-rational Sherlock Holmes believe in fairies? That question has baffled readers and historians alike for nearly a century. Arthur Conan Doyle, the brilliant mind behind one of literature’s most iconic characters, was a man of deep contradiction. At once a scientist and a mystic, a crusader for justice and a champion of spiritualism, Doyle lived a life that stretched far beyond the shadow of Baker Street. To know him is to understand the tension between faith and fact, logic and longing, that defined the man and his age.

Arthur Ignatius Conan Doyle was born on May 22, 1859, in Edinburgh, Scotland, into a large Irish Catholic family. His father, Charles Altamont Doyle, suffered from alcoholism and mental illness, and the family was often beset by poverty and instability. With the support of wealthy uncles, Doyle was sent to Jesuit schools in England and later to Feldkirch, Austria. These early years exposed him to both rigid Catholic instruction and a broader European education. Though raised in the faith, he ultimately rejected Catholicism and became an agnostic, setting the stage for his lifelong search for spiritual meaning.

Doyle enrolled in the University of Edinburgh Medical School in 1876, where he came under the influence of Dr. Joseph Bell, a professor known for his uncanny powers of observation and deduction. Bell’s methods became the inspiration for Sherlock Holmes, whose fictional logic and clinical clarity were rooted in real-life diagnostic science. Doyle earned his Bachelor of Medicine and Master of Surgery degrees in 1881, and completed his M.D. in 1885 with a dissertation on tabes dorsalis, a degenerative neurological condition.

In 1882, Doyle opened a medical practice in Southsea, near Portsmouth. The practice was slow, and in the long hours between patients, he began to write in earnest. His first published story, “The Mystery of Sasassa Valley,” appeared in 1879. Eight years later, he introduced Sherlock Holmes and Dr. Watson in A Study in Scarlet, sold for just £25. Though the initial payment was modest, the story’s impact was immense. As stories appeared regularly in The Strand Magazine, Holmes quickly became a household name.

Doyle, however, viewed Holmes as both a blessing and a burden. He once wrote to his mother that he considered “slaying Holmes” to make room for what he deemed “better things.” In 1893, he did just that, sending Holmes and his nemesis Moriarty tumbling to their apparent deaths in The Final Problem. But the public outcry was so intense that Doyle eventually brought Holmes back—first in The Hound of the Baskervilles (set earlier in the character’s timeline) and then fully resurrected in 1903’s The Adventure of the Empty House. Over time, he would write four Holmes novels and 56 short stories.

Doyle considered his historical fiction—such as The White Company and Sir Nigel—his literary high mark. He also created other memorable characters, including the scientific adventurer Professor Challenger, featured in The Lost World (1912), and the Napoleonic-era hero Brigadier Gerard. He wrote plays, poetry, war histories, and even science fiction, reflecting the breadth of his literary ambition.

Outside of literature, Doyle engaged deeply with public life. During the Second Boer War, he served as a volunteer physician at a field hospital in Bloemfontein and later wrote The Great Boer War and The War in South Africa: Its Cause and Conduct, the latter defending Britain’s military actions and helping earn him a knighthood in 1902. He stood unsuccessfully for Parliament twice as a Liberal Unionist and remained involved in military and civic issues throughout his life.

His interest in justice extended to real-life criminal cases. In 1906, he championed the cause of George Edalji, a mixed-race solicitor wrongly imprisoned for animal mutilation and threatening letters. Doyle’s investigation exposed flaws in the case and led to Edalji’s release—helping prompt the creation of the Court of Criminal Appeal. He later took up the case of Oscar Slater, a German-Jewish gambler wrongly convicted of murder in Glasgow. After years of effort, Slater’s conviction was quashed in 1928, due in no small part to Doyle’s relentless advocacy.

Despite his scientific training and rational persona, Doyle was a lifelong believer in the supernatural. As early as the 1880s, he attended séances and joined psychical research societies. In 1916, amid the carnage of the First World War and influenced by the apparent psychic abilities of his children’s nanny, Doyle publicly embraced spiritualism. His son Kingsley died in 1918 from pneumonia after being wounded at the Somme—a personal loss that deepened his belief in communication with the dead.

Doyle became one of the most prominent spiritualist voices in the world. He wrote The New Revelation (1918), The Vital Message (1919), The History of Spiritualism (1926), and The Coming of the Fairies (1922), in which he endorsed photographs supposedly depicting actual fairies, taken by two girls in Cottingley, Yorkshire. The photos were later admitted to be hoaxes, but Doyle never renounced his belief in their authenticity.

His fervent spiritualism caused a rift with the magician Harry Houdini, who initially concealed his skepticism but eventually clashed with Doyle in public and private. After an infamous séance in which Lady Doyle claimed to contact Houdini’s mother—who, puzzlingly, wrote in perfect English and opened with a Christian blessing—Houdini became a vocal critic of mediums. Their friendship collapsed, with Doyle accusing Houdini of suppressing spiritual truth, and Houdini labeling Doyle as tragically gullible.

Doyle’s life was not all writing and public crusades. He was an accomplished sportsman—playing first-class cricket, skiing in Switzerland, boxing, golfing, and even designing a golf course in Canada. He founded the Undershaw Rifle Club to promote marksmanship among civilians and took a deep interest in architecture, designing parts of his own home and even modifying a hotel in Hampshire. He captained literary cricket teams and wrote of W.G. Grace, the only first-class wicket he ever took as a bowler.

He was married twice. His first wife, Louisa Hawkins, died of tuberculosis in 1906. A year later, he married Jean Leckie, whom he had loved for years but remained faithful to Louisa until her death. He had five children—two with Louisa and three with Jean. None of them had children of their own, leaving Conan Doyle with no living direct descendants.

Arthur Conan Doyle died on July 7, 1930, at his home in Crowborough, Sussex. At his funeral, spiritualists gathered to celebrate his passage “beyond the veil.” A week later, thousands assembled in London’s Royal Albert Hall for a séance in his honor, during which a medium claimed to make contact with his spirit.

To the world, Doyle will always be the man who gave us Sherlock Holmes. But he was more than the sum of his literary output. He was a seeker—a man of science who believed in spirit, a rationalist who saw beyond reason, a creator of logic who longed for mystery. That paradox is not a flaw but the essence of Arthur Conan Doyle’s genius.

Leave a comment