The wind howls over the cliffs of the Judaean Desert as though echoing ancient cries. The sun rises slow and pitiless over the Dead Sea, throwing light across the broken ruins of a fortress carved into an impossible mesa. Here, they say, nearly a thousand Jewish men, women, and children made their final stand. Here, the defenders chose death over Roman chains. Here, Masada became legend.

Listen to the Article (appx 8:11)

The year was 73 CE. The Jewish world was already in tatters. Jerusalem had fallen three years earlier. The Second Temple—center of faith and national identity—was reduced to rubble. Survivors of the Roman fury had scattered, hunted, hounded, and cornered. Among the most determined were the Sicarii, a radical splinter of the Zealot movement, infamous for their daggers and their defiance. They had seized Masada back in 66 CE, taking it by surprise from a Roman garrison. Now, they watched the desert and waited for what would surely come.

I had wanted to (and was approved to) make the path climb, but it was closed that day for maintenance.

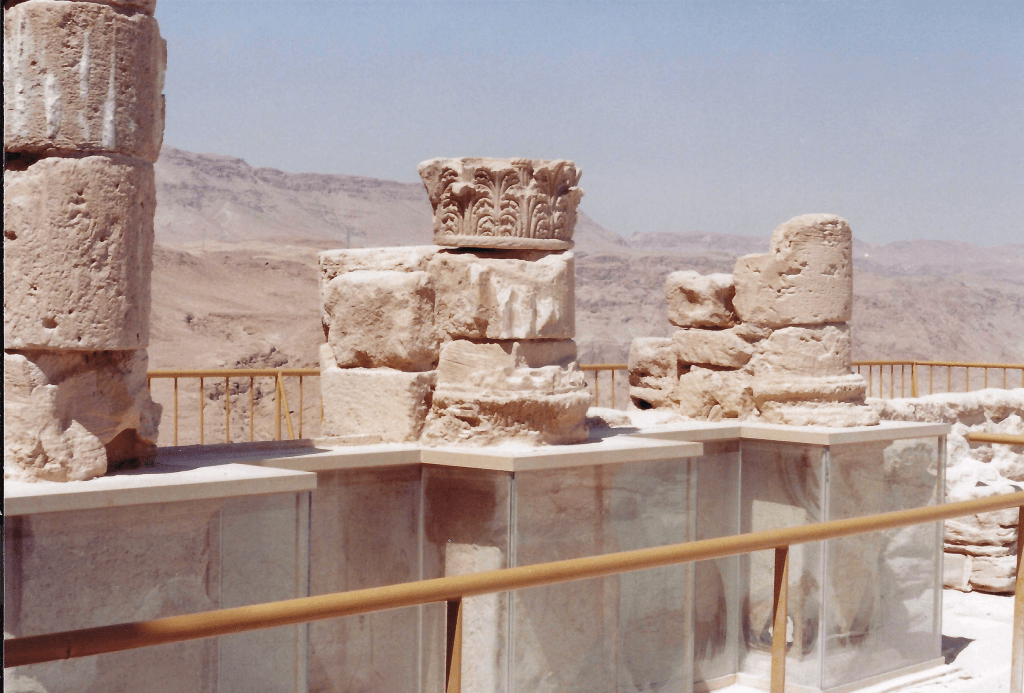

Masada itself was no ordinary mountain. Rising more than 1,300 feet above the desert floor, its flat top covered over 18 acres. It was a palace, a fortress, and a sanctuary all at once. Herod the Great had fortified it decades earlier, building massive walls, water cisterns, and two royal palaces designed both for luxury and survival. This was not a place meant to be taken. It was a fortress to be endured in, to outlast sieges and ride out rebellions. That is exactly what made it so appealing to the Sicarii and their leader, Eleazar ben Ya’ir.

Eleazar was no warlord drunk on violence. If anything, he was a zealot animated by religious purity, national desperation, and a profound belief that Rome had not only conquered Israel but desecrated it. He and his followers held fast to the idea that to live under Roman rule was to betray both God and history. Masada was not just a redoubt. It was a declaration.

Their opponent was Lucius Flavius Silva, governor of Judaea and commander of Legio X Fretensis. Rome did not tolerate embers. It extinguished them. Silva led some 8,000 soldiers, plus thousands more auxiliaries, Jewish prisoners, and engineers. He faced fewer than 1,000 defenders, including women and children. But Masada, by any standard, was a nightmare for siege warfare. The Snake Path that snaked up its northeastern slope was narrow and exposed. The rest was sheer cliff. To breach Masada, Silva had to do what Rome did best—build.

And build they did. The Romans constructed a circumvallation wall over two miles long, enclosing the mountain to prevent escape. Then they turned to the mountain’s western slope and began building a siege ramp—a monumental earthwork hundreds of feet high. Stones, dirt, timbers. Day after day, with the sun beating down and defenders firing from above, they moved the mountain, one basketful at a time. The ramp still exists. You can climb it today.

For centuries, the prevailing wisdom held that the siege lasted months, maybe years. But new archaeological research has challenged that view. Studies published in the Journal of Roman Archaeology suggest the entire siege ramp and surrounding fortifications may have been completed in just a matter of weeks. By using photogrammetry, aerial drone surveys, and manpower analysis, researchers estimate that with a few thousand men, the whole system could have been built in 11 to 16 days. The lack of extensive camp debris—normally expected from a long encampment—supports that theory. From Rome’s perspective, this was not a drawn-out war story. It was a brief, brutal statement of power.

Josephus, the first-century Jewish historian turned Roman citizen, gives us the only surviving narrative of what happened at Masada. Captured earlier in the war, Josephus had switched sides, and his account was likely drawn from Roman field commentaries, with some flourishes of drama. According to him, when the Romans breached the wall with a siege tower and battering ram on April 16, 73 CE, they found silence. The defenders had set fire to most of their buildings—except the storerooms, which remained miraculously intact—and had taken their own lives. Nine hundred sixty people were dead. Only two women and five children, hidden in a water conduit, survived to tell the story.

According to Josephus, the Sicarii had drawn lots to determine who would kill whom, in order to avoid suicide, which Jewish law forbade. The last man alive fell on his own sword. It is an agonizing tale, one that forces even the modern reader to wrestle with questions of faith, dignity, extremism, and despair.

But did it happen?

The archaeological evidence is not unanimous. Excavations led by Israeli archaeologist Yigael Yadin in the 1960s confirmed many of Josephus’s details—Herod’s palaces, the Roman camps, even the synagogue and bathhouse—but they did not confirm the mass suicide. Remains of fewer than thirty bodies were ever found. Many buildings showed fire damage, but not just one. Josephus described a single palace—two were found. The discrepancies do not mean Josephus lied, but they do cast a long shadow on his reliability.

Some scholars argue the Masada story was embellished, or even partially invented, to serve a narrative purpose. Others believe the suicides happened but on a smaller scale, or that some defenders escaped. Still others argue that Josephus was reporting the story he was told by the surviving women, themselves perhaps not eyewitnesses to the entire event. What is undeniable is that Masada has lived far beyond its archaeological footprint.

In the 20th century, Masada became a national symbol in Israel—a story of defiance and heroism against impossible odds. For a new state built from Holocaust ashes and surrounded by hostile powers, Masada was a rallying cry. Israeli military units took oaths of allegiance atop its heights. The phrase “Masada shall not fall again” became part of the national lexicon.

But with time came nuance. The Sicarii, after all, were not universally admired. Even in Josephus’s account, they are portrayed as extremists who murdered fellow Jews in the town of Ein Gedi. Their vision of resistance was not shared by all. Some Israeli historians and educators began questioning whether Masada should be a model of national identity or a solemn reminder of how zealotry can lead to ruin. Masada is both history and memory. It is both fact and faith.

There is no denying the psychological power of that moment—real or constructed—when a community of outcasts, cut off from the world, facing certain doom, chose autonomy over subjugation. Whether one sees that choice as courageous or tragic depends as much on the reader’s heart as on the scholar’s eye.

The tale of Masada is not simply about walls and weapons. It is about the eternal Jewish tension between survival and surrender, between assimilation and resistance. It is a story about how people remember, and why they remember, and what they choose to make sacred. In the end, the mountain still stands, the wind still howls, and somewhere beneath the sand and stone, the voices of the past still whisper their truths.

And that, perhaps, is the real legacy of Masada. Not a clean moral lesson, not a neat ending, but a fracture. A fracture in the line between history and myth. Between heroism and fanaticism. Between what happened, what we believe happened, and why we need to believe it.

The Romans took Masada. That much is sure. But what they could not take—and what the world still wrestles with—is the meaning left behind.

Leave a comment