The call for war by President Woodrow Wilson on April 2, 1917, did not erupt from a moment of impulse or bluster. It came at the tail end of a long, grinding moral tug-of-war that had left the United States straddling a fault line between its founding ideals and the brutal realities of the modern world. For nearly three years, Wilson had danced delicately on the tightrope of neutrality, dodging pressure from Wall Street bankers, hawkish Anglophiles, impassioned pacifists, and an immigrant-rich populace with loyalties split across the Atlantic. But Germany, with its stubborn faith in the power of submarines and a telegram that read like the plot of a dime-store spy novel, finally kicked the legs out from under that tightrope.

Listen to the Article (appx 5:14)

Germany’s unrestricted submarine warfare had already claimed American lives before, most notably with the sinking of the Lusitania in 1915. In response, Germany issued the Sussex Pledge, promising to limit attacks on passenger and merchant ships. But by January 1917, the German military leadership, believing they could cripple Britain before the United States could effectively intervene, persuaded Kaiser Wilhelm II to abandon that promise. Germany resumed unrestricted submarine warfare, declaring that any ship, regardless of flag, would be fair game in certain war zones.

Then came the Zimmermann Telegram—Germany’s clandestine offer to help Mexico regain Texas, New Mexico, and Arizona in exchange for joining the Central Powers. Intercepted and decoded by British intelligence and forwarded to the United States, the message shocked the American public when made public by Wilson in March 1917. The idea that Germany was actively courting America’s neighbor for an attack added fuel to growing outrage, especially after American ships continued to be sunk in the Atlantic.

But this was not a nation marching in lockstep toward war. The United States in 1917 was divided. On one side stood Wilson, freshly reelected on the slogan “He kept us out of war,” backed by internationalists, large financial institutions with loans to the Allies, and moralists who viewed the war as a crusade. On the other stood a formidable anti-war coalition: former Secretary of State William Jennings Bryan, Senators Robert La Follette and George Norris, industrialist Henry Ford, peace advocate Jane Addams, and Socialist leader Eugene V. Debs. Many saw the war as an imperialist fight between corrupt old-world powers. Immigrant communities, especially German and Irish Americans, were wary of entangling themselves in a European struggle that did not feel like their own.

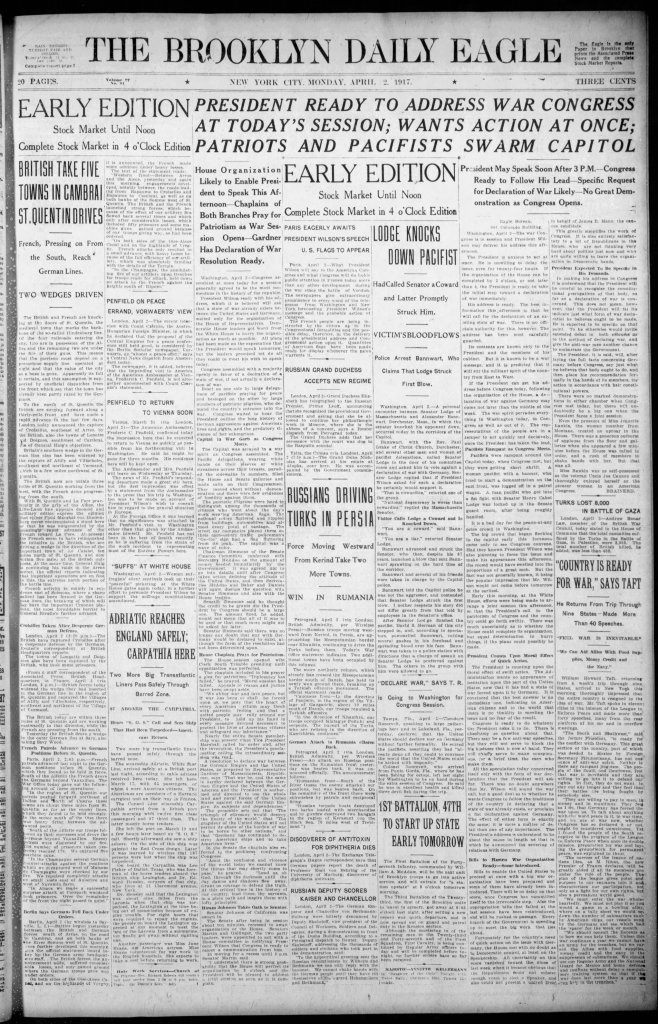

When Wilson addressed Congress on April 2, 1917, he stood not just as a president, but as a professor of principle. With the precision of a scholar and the cadence of a preacher, he laid out a clear indictment: Germany’s submarine warfare was not just a threat to commerce—it was a war against mankind. He made no calls for revenge, no demands for territory. Instead, he summoned Congress to act in defense of democracy, for “the rights and liberties of small nations,” and to “make the world safe for democracy.”

The response was swift and electrifying. The galleries erupted in applause. Newspapers across the country hailed the moral clarity of the speech. But in the halls of Congress, debate raged. In the Senate, six members stood against the resolution. In the House, fifty resisted the call to arms. Yet on April 4, the Senate voted 82 to 6 in favor of war. The House followed on April 6, voting 373 to 50. That same day, Wilson signed the declaration. The United States was at war.

The legacy of Wilson’s speech remains complex. It marked the moment the United States fully committed to shaping the world beyond its shores. But it also exposed deep rifts in American society. The war brought with it conscription, the Espionage and Sedition Acts, and the imprisonment of dissenters like Debs. It also brought 116,000 American deaths, a transformed economy, and a postwar climate filled with both triumph and trauma.

In April of 1917, Woodrow Wilson climbed the steps of the Capitol and asked Congress not for conquest, but for courage. He gave the nation a reason to fight—not for land or gold, but for a principle. And in doing so, he launched the United States into the storm of the twentieth century. The world would be made safe for democracy, perhaps—but not without cost. Not without consequence. And certainly, not without controversy.

Leave a comment