When we think about the art of political commentary, we often imagine witty editorial cartoons that can distill complex issues into a single image, packed with symbolism, satire, and poignancy. Much of the credit for transforming political cartoons into a powerful vehicle for social and political discourse belongs to Thomas Nast, a German-born American artist whose work in the 19th century not only influenced elections but also shaped the very symbols of American politics. His iconic caricatures of Boss Tweed, his depiction of Santa Claus, and his popularization of the Democratic donkey and Republican elephant have left an indelible mark on the cultural and political landscape of the United States.

Before Nast, the American political cartoon was a modest medium, offering occasional commentary on current events. It existed in the shadow of Europe, where artists like James Gillray and Honoré Daumier had pioneered satirical depictions of political figures. However, in the United States, political cartoons truly found their voice during the Civil War and Reconstruction eras. These were periods of intense social and political upheaval when complex issues demanded new ways to engage the public. With rising literacy rates and widespread access to newspapers, editorial cartoons became an essential tool for shaping public opinion.

Thomas Nast’s entry into this world coincided with these transformative times. Born in 1840 in Landau, Bavaria, Nast emigrated to New York with his family as a young boy. His early passion for art was evident, though his academic studies were less impressive. At the tender age of 15, he joined Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper as a draftsman, and later, Harper’s Weekly, where he found the ideal platform for his burgeoning talent.

Nast’s career blossomed during the Civil War. His vivid illustrations rallied support for the Union and condemned slavery, earning him praise from none other than Abraham Lincoln, who called him “our best recruiting sergeant.” However, Nast’s most enduring contributions came after the war, during the Gilded Age, when he turned his pen against corruption and political malfeasance.

In the 1860s and 1870s, New York City politics were dominated by Tammany Hall and its infamous leader, Boss William M. Tweed. Tweed’s political machine had entrenched itself through a combination of patronage, vote-buying, and outright theft from public coffers. Nast’s cartoons in Harper’s Weekly exposed Tweed’s corruption to a broad audience. One particularly biting cartoon, “The Tammany Tiger Loose,” depicted Tweed’s organization as a ravenous beast devouring New York City. Tweed reportedly said, “My constituents don’t know how to read, but they can’t help seeing them damn pictures.”

Nast’s relentless campaign contributed significantly to Tweed’s downfall. By 1871, Tweed was removed from power, and later, when he escaped to Spain, authorities identified him using one of Nast’s caricatures. The triumph solidified Nast’s reputation as a champion of reform.

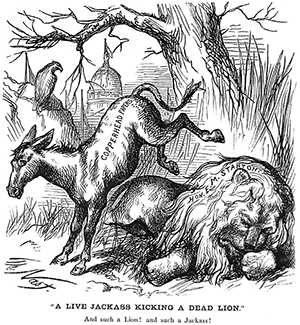

Among Nast’s most notable innovations was his use of animals as symbols for political parties. On January 15, 1870, Nast published a cartoon in Harper’s Weekly titled “A Live Jackass Kicking a Dead Lion.” The donkey, representing the Democratic Party’s Copperhead faction, was shown mocking the late Secretary of War Edwin Stanton, symbolized by the lion. The image resonated deeply with readers and helped cement the donkey as a symbol of the Democratic Party, though it had been sporadically associated with the Democrats since the days of Andrew Jackson.

Four years later, Nast introduced the Republican elephant in a cartoon titled “The Third-Term Panic.” Here, the elephant represented the Republican vote, depicted as a lumbering yet powerful force that could be frightened by rumors of Ulysses S. Grant seeking a third presidential term. Together, these symbols became enduring icons of American political identity, still instantly recognizable today.

Nast’s cartoons were characterized by bold, intricate cross-hatching and meticulous attention to detail. He combined allegory, humor, and sharp criticism, ensuring that his images could be understood by both the educated elite and the common reader. His work often included dramatic contrasts between light and shadow, adding depth to his satirical commentary.

While Nast’s legacy includes many positive contributions, his work was not without controversy. Some of his cartoons contained anti-Catholic and anti-Irish sentiments, reflecting prevalent biases of his time. His portrayals of Irish immigrants as violent and drunken were harsh and, by today’s standards, deeply problematic. These aspects of his work complicate his legacy, serving as a reminder that even the most influential figures are products of their era.

Thomas Nast died in 1902, serving as U.S. Consul General in Guayaquil, Ecuador. By the end of his life, his influence had waned; new artists and changing tastes had relegated his style to the past. Yet, his impact on American culture remains profound.

Today, political cartoons continue to serve as a vital form of expression, holding the powerful accountable and fostering public debate. Nast’s ability to distill complex issues into iconic images set the standard for generations of cartoonists. His work reminds us that art can be more than entertainment; it can be a catalyst for change.

For Conservative Talk Radio listeners, Nast’s story resonates in its defense of integrity and accountability. His unwavering commitment to exposing corruption and promoting justice underscores the enduring power of individual conviction. As we reflect on his legacy, we are reminded of the enduring importance of holding leaders accountable—and the remarkable ability of a simple drawing to shape the course of history.

Leave a comment