On February 20, 1792, President George Washington signed a law that most Americans today have never read and rarely discuss. It did not declare war. It did not annex territory. It did not expand suffrage. It did not even lower taxes.

It built roads.

More precisely, it built a system of roads and offices designed to carry letters and newspapers across a fragile, experimental republic. Yet beneath that practical exterior lay something far more ambitious. The Postal Act of 1792 was not simply about delivery. It was about survival. It was about whether a sprawling republic could remain united without dissolving into regional suspicion and political isolation.

The generation that drafted and ratified the Constitution had lived through fragmentation. Under the Articles of Confederation, the states drifted. Communication was slow, uneven, and unreliable. Rumor traveled faster than verified information. Local loyalties overshadowed national coherence. The Founders understood that distance breeds distrust. If citizens in Massachusetts could not regularly know what was happening in Georgia, or if farmers in Kentucky had no reliable channel to the political debates unfolding in Philadelphia, the idea of one nation would become theoretical at best.

The Constitution anticipated this problem. Article I, Section 8, Clause 7 grants Congress the authority “To establish Post Offices and post Roads.” It is a short line, almost easy to overlook, but it sits among the enumerated powers of taxation, defense, and commerce. That placement is telling. The circulation of information was considered as fundamental as the raising of armies or the regulation of trade.

This authority was not a casual administrative convenience. It was a structural necessity.

To grasp why the 1792 Act mattered so much, one must look backward to the colonial experience. Under British administration, the postal system functioned within an imperial framework. It generated revenue. It facilitated commerce. But it was also widely believed to be vulnerable to inspection and manipulation. Colonists harbored suspicions that correspondence could be monitored, that information might flow upward to London in ways that served imperial control rather than colonial autonomy. Whether every suspicion was justified matters less than the perception. Trust in communication is the oxygen of political liberty. Without it, civic life suffocates.

In 1774, amid escalating tensions, William Goddard proposed the creation of an independent postal system for the colonies. With support from figures including Benjamin Franklin, this “Constitutional Post” emerged as a patriotic alternative to the Royal Mail. It was designed to ensure secure and reliable communication among the colonies as they moved toward resistance and ultimately revolution. The effort demonstrated something profound: a network of communication is not neutral. It either reinforces authority or distributes it.

Franklin’s earlier tenure as colonial postmaster had already introduced logistical improvements. He standardized routes, calculated distances carefully, and emphasized speed and efficiency. His experiments with overnight mail were not mere technical feats. They proved that a vast geography could be navigated systematically. Franklin understood that information delayed is influence denied.

By the time independence was secured, the young nation had operated under temporary postal arrangements born of wartime necessity. But temporary measures are not foundations. The question facing Congress in the early 1790s was whether to treat the postal system as a revenue mechanism or as an instrument of republican cohesion.

The answer they chose reveals their priorities.

The Act of 1792 established a permanent Post Office Department. It did not simply continue prior practice; it formalized and expanded it. This was the transition from improvisation to institution. The republic was no longer fighting for existence. It was now designing its infrastructure for endurance.

Central to that design was control.

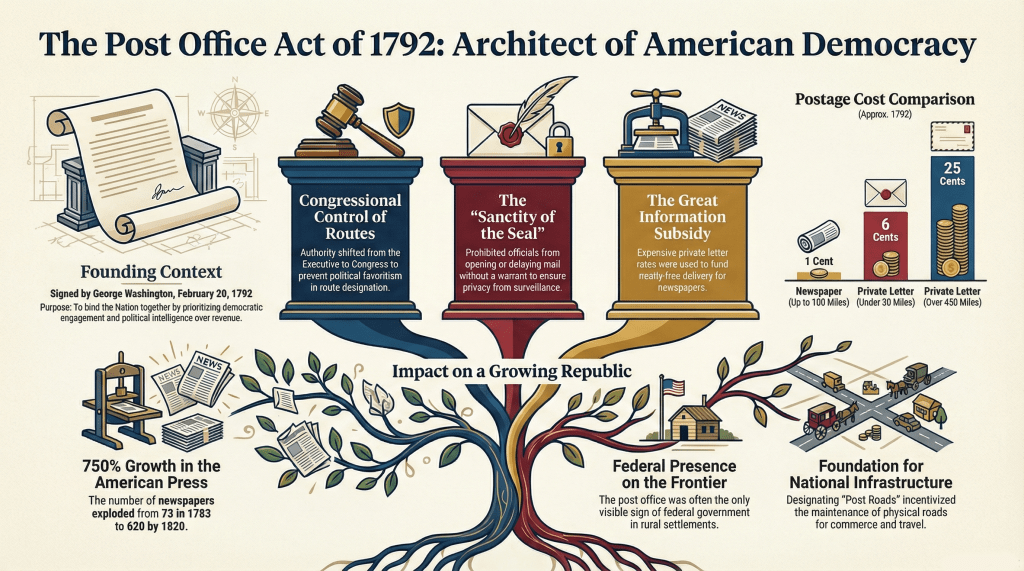

One of the Act’s most consequential provisions transferred the authority to designate postal routes from the executive branch to Congress. This may appear procedural, but it was anything but trivial. In monarchies and centralized systems, control of communication routes often resides with the executive. That arrangement invites favoritism and manipulation. A president could reward political allies with enhanced connectivity or isolate opponents by neglecting their regions.

The framers of the Act rejected that possibility. By placing route designation firmly in legislative hands and explicitly listing many routes in statute, they constrained executive discretion. Communication would not be a tool of patronage. It would be a shared national utility.

Imagine the alternative. If a chief executive could quietly redirect or withhold postal service, dissenting communities might find themselves cut off from national dialogue. News would slow. Political organizing would falter. A republic dependent on informed citizens would weaken from within.

The 1792 framework anticipated that danger and blocked it at the outset.

But the architects of this system were not content merely to prevent abuse. They sought to cultivate engagement. The Act embedded a philosophy of nation-building within its rates and regulations. It recognized that a republic thrives when citizens can access political information consistently and affordably.

The postal system would therefore not operate solely according to market logic.

In a purely commercial model, postage rates would align strictly with cost and profitability. Newspapers, bulky and often low-margin, might be expensive to circulate. Rural distribution could be neglected. Private correspondence from merchants and professionals might dominate the network.

Congress chose a different path. It recognized that newspapers served a civic function beyond private gain. They transmitted debates, reported legislative proceedings, and enabled citizens to monitor their representatives. In short, they were instruments of accountability.

To protect that function, the Act established preferential rates for newspapers. They could travel at remarkably low cost compared to private letters. This was not an oversight or a subsidy born of accident. It was intentional. Expensive personal correspondence would help finance inexpensive public information.

The logic was simple and bold. Commerce would underwrite citizenship.

At the same time, the Act reinforced the integrity of private mail. It made clear that postal officials could not arbitrarily detain or open correspondence. Severe penalties attached to tampering. In an era still haunted by fears of surveillance, these provisions mattered deeply. A republic that reads the mail of its citizens without restraint ceases to be a republic in spirit, whatever its formal structure.

Thus, the Postal Act of 1792 fused three elements into one coherent system: legislative control to prevent executive overreach, preferential treatment for civic information, and legal protections to preserve trust.

What emerged was not merely a delivery network. It was an institutional answer to a profound political question: How does a geographically expansive republic remain intellectually unified without resorting to coercion?

The Founders’ answer was to build channels rather than chains.

Roads instead of restrictions.

Circulation instead of command.

By the time Washington affixed his signature, the framework was set. Routes would stretch from the Atlantic seaboard into the interior. Newspapers would traverse distances once thought prohibitive. Letters would move under legal protection. And a vast territory would begin to feel, slowly but unmistakably, like a single political organism.

The nervous system of the republic had been laid down.

Segment Two

A Flood of Ink and the Making of a National Mind

If the first achievement of the Postal Act of 1792 was structural, the second was cultural. Once the legal framework and routes were established, something began to move across those roads that was far more powerful than parcels or private letters.

Ideas began to circulate at scale.

The architects of the Act understood that a republic cannot rely on proximity. It cannot depend on citizens gathering in a single square to hear a single orator. The United States was already too large for that model, and it was expanding. What the nation required was not a town hall. It required a web.

The most important thread in that web was the newspaper.

Under the 1792 Act, newspapers enjoyed astonishingly low postage rates. A paper could be sent up to one hundred miles for a single cent, and only slightly more for greater distances. Compared to the six to twenty-five cents required for private letters, the disparity was striking. This was not an accident of accounting. It was policy in action.

The reasoning was unapologetically civic. Newspapers carried political debate, legislative reports, election results, and commentary. They connected farmers to Congress, merchants to treaties, and voters to the conduct of officials. In a monarchy, the crown fears the uncontrolled spread of printed criticism. In a republic, the spread of criticism is the bloodstream of legitimacy.

Cheap newspaper postage meant that editors could expand circulation without pricing out rural readers. It meant that even modest communities could sustain a paper that reached beyond its immediate locality. It meant that political ideas would not be confined to urban elites.

But the Act went further.

It permitted what became known as the Printer’s Exchange. Newspaper printers were allowed to exchange copies with one another free of charge. This seemingly technical provision created something revolutionary. An editor in Boston could receive a paper from Philadelphia, extract an article, and reprint it for local readers. A rural printer in Kentucky could reprint speeches from New York or congressional debates from the capital.

The result was not uniformity. It was cross-pollination.

Arguments moved. Perspectives collided. Regional concerns entered national conversations. The United States began to develop what might be called a shared political vocabulary.

By the early decades of the nineteenth century, the growth was unmistakable. In 1783, the nation had only a few dozen newspapers. Within a generation, that number multiplied many times over. The rise cannot be explained solely by population growth. The postal subsidy and exchange system created the conditions for expansion.

What emerged was a national market for information long before a comparable market for goods fully developed. Citizens in distant states read about controversies over the national bank, foreign policy disputes, and constitutional interpretation. They responded with letters, editorials, and organizing efforts of their own.

This was noisy. It was partisan. It was frequently intemperate. But it was vibrant.

The republic did not depend on unanimity. It depended on engagement.

The postal system enabled that engagement at scale. It allowed political factions to coordinate across state lines. It allowed reform movements to disseminate arguments beyond their local bases. It allowed voters to monitor officials who governed far from their daily lives.

There is a tendency today to romanticize early American politics as measured and decorous. The historical record tells a different story. The 1790s were combative. Newspapers often served as organs of political parties. Federalists and Democratic-Republicans launched blistering critiques of one another. Accusations flew. Reputations suffered.

Yet the very intensity of the debate demonstrates the success of the infrastructure. The public sphere was alive.

Without cheap newspaper circulation, the arguments over the Jay Treaty, the Alien and Sedition Acts, or the Louisiana Purchase would have remained confined to a narrow elite. Instead, they reached taverns, farms, workshops, and frontier settlements.

The Post Office did not dictate the content of that discourse. It enabled it.

Beyond politics, the postal network also carried economic intelligence. Commodity prices, shipping schedules, land sales, and commercial notices moved through newspapers and letters alike. Merchants relied on timely information to make decisions in a volatile economy. Farmers depended on news of markets and weather patterns in distant regions.

Although the Act prioritized political information, it did not neglect commerce. By designating post roads and guaranteeing regular service, Congress indirectly encouraged the maintenance and expansion of physical transportation routes. Roads that carried mail also carried goods. Stagecoaches that transported letters often transported passengers and small freight.

In this way, the postal system served as a catalyst for broader infrastructural development. It incentivized connectivity. Communities petitioned for inclusion along routes, recognizing that to be bypassed was to be marginalized.

Perhaps the most transformative impact occurred on the frontier.

For settlers pushing into western territories, isolation was a daily reality. Distance from established cities meant limited access to information and limited influence over national decisions. The arrival of mail altered that equation.

A post office, often modest in appearance, signaled more than convenience. It represented incorporation. It told settlers that they were part of the same political community as citizens on the eastern seaboard. Through newspapers and correspondence, they could follow congressional debates, read presidential messages, and participate in elections with knowledge rather than guesswork.

The frontier did not feel quite so remote when the latest news from the capital arrived on schedule.

This phenomenon has been described as the contraction of space. The miles between communities did not physically shrink, but their psychological and political distance narrowed. A letter could traverse hundreds of miles under legal protection. A newspaper could carry arguments across state lines in a matter of days.

That reliability mattered.

In fragile republics, neglect breeds resentment. If citizens believe they are forgotten, they may withdraw loyalty. By extending consistent service into remote regions, the federal government signaled commitment. It did not need to station troops in every settlement to demonstrate presence. A mail carrier often sufficed.

Yet this system was not utopian.

The very openness that allowed ideas to circulate also exposed tensions. As the nation confronted divisive issues, the postal network became a battleground. In later decades, for example, the distribution of abolitionist literature provoked controversy. Some communities resisted the delivery of materials they deemed incendiary. Questions arose about whether the commitment to free circulation of information would withstand sectional pressures.

These conflicts reveal something essential. The Postal Act created infrastructure for debate, but it could not eliminate disagreement. It empowered citizens to argue, persuade, and mobilize. That empowerment sometimes intensified division before producing resolution.

Such is the paradox of liberty.

Still, the broader trajectory is unmistakable. The Act embedded within the federal system a commitment to accessible information. It treated communication not merely as a service but as a public good.

In doing so, it advanced literacy and civic awareness. When newspapers are affordable and widely distributed, reading becomes a habit tied to citizenship. Engagement becomes routine rather than exceptional.

The republic began to develop what might be called a national mind, not because everyone agreed, but because everyone participated in a shared informational ecosystem.

The roads carried more than ink and paper. They carried arguments, aspirations, anxieties, and ambitions. They carried the pulse of a country discovering itself in print.

And as that pulse strengthened, the question shifted from whether the republic could survive to how it would manage the tensions unleashed by its own vitality.

Those tensions would test the durability of the architecture laid down in 1792.

Segment Three

Liberty, Loopholes, and the Long Shadow of Universal Service

No institution designed by human beings remains untouched by human ambition. The postal system that helped cultivate a national conversation would, in time, become a mirror of the nation’s virtues and its vices. The very scale that made it indispensable also made it tempting.

The framers of the 1792 Act were not naïve. They knew power accumulates where networks converge. That is why they embedded protections for privacy so prominently within the law. Mail was not to be detained, delayed, or opened arbitrarily. Severe penalties awaited tampering. Robbing the mail could carry the harshest consequences available under federal law. The message was unmistakable. Trust is not optional. It must be guarded.

Yet as the system matured, complications emerged.

One of the earliest tensions arose from what became known as the Dead Letter Office. When mail could not be delivered because of incomplete addresses, unknown recipients, or other logistical failures, it required processing. In some cases, undeliverable letters were opened to identify senders or recover valuables. Administratively practical, yes. Philosophically simple, no.

Here lay a dilemma. The sanctity of sealed correspondence stood at the heart of republican trust. But operational reality demanded procedures for dealing with abandoned or misdirected mail. The tension between privacy and internal security did not begin in the twentieth century. It was embedded in the infrastructure from the start.

The existence of such a loophole did not negate the Act’s commitment to liberty, but it revealed something enduring about democratic governance. Principles must survive contact with administration. Every safeguard requires interpretation. Every interpretation risks erosion.

Beyond privacy concerns, political dynamics exerted pressure on the department in another direction.

The postal network expanded rapidly. New communities required post offices. Each office required a postmaster. These were federal appointments scattered across towns and counties throughout the nation. In an era before a large standing bureaucracy, these positions represented one of the most extensive points of federal presence in daily life.

Where appointments exist, politics follows.

By the early nineteenth century, the Post Office had become intertwined with what later generations would label the spoils system. Political parties rewarded loyal supporters with postmaster positions. Control of the presidency often meant influence over thousands of local offices. What had been designed as a civic network became, in part, a mechanism for patronage.

To understand this development, one must appreciate the magnitude of the system. The postal department grew into one of the largest civilian employers in the federal government. Its reach extended further than most other agencies. In many towns, the postmaster was the face of federal authority.

Partisan loyalty thus became a qualification, sometimes overshadowing administrative competence. Critics argued that the department’s neutrality suffered. Supporters countered that local appointments fostered political participation and accountability.

Again, the architecture held, but the pressures intensified.

The postal system also faced ideological tests as the republic matured. In the 1830s, the circulation of abolitionist literature through the mail ignited controversy in southern states. Some local officials refused to deliver materials they deemed incendiary or dangerous to public order. The question was stark. Would the commitment to the free flow of information withstand sectional hostility?

The original framework of the 1792 Act favored circulation rather than suppression. Newspapers and printed materials enjoyed preferential rates precisely to encourage dissemination. Yet political realities strained that commitment. The postal network became an arena in which broader conflicts over speech, slavery, and federal authority played out.

It is easy, from a modern vantage point, to judge these episodes in isolation. It is more instructive to see them as stress tests of a foundational principle. The United States had chosen to make communication a public good. That choice required tolerating uncomfortable ideas. It required resisting the impulse to restrict channels when messages offended prevailing norms.

The durability of the system lay not in its perfection but in its adaptability. Reforms occurred. Procedures evolved. Rates changed.

In 1845 and again in 1851, Congress reduced letter postage rates significantly. Advances in transportation and increased volume made lower prices feasible. What had once been a costly form of communication became increasingly accessible to ordinary citizens. The trend reinforced the notion that postal service was not a luxury but a right embedded within citizenship.

The idea of universal service took shape gradually. The federal government assumed responsibility for delivering mail to all communities, regardless of profitability. Urban centers might generate surplus revenue, while rural routes incurred higher costs. Yet the commitment persisted. Geography would not determine inclusion.

This principle stands as one of the most enduring legacies of the 1792 framework. It affirmed that national cohesion demands shared infrastructure. A farmer in a remote valley deserved the same access to communication as a merchant in a coastal city. Profit margins would not dictate belonging.

Over time, technological revolutions altered the mechanisms but not the underlying philosophy. Railroads accelerated delivery. Telegraph lines introduced instantaneous communication. Eventually, the postal department transformed into the modern United States Postal Service in 1970, operating under a revised organizational structure. Yet the central idea endured.

Communication binds.

The republic’s founders did not imagine email or digital networks. They imagined roads and riders. But the principle they enshrined remains relevant. A self-governing people cannot deliberate collectively without reliable channels. They cannot hold officials accountable if information is scarce or prohibitively expensive. They cannot cultivate shared identity if regional isolation prevails.

The Postal Act of 1792 did not eliminate division. It did not prevent patronage. It did not resolve every tension between liberty and administration. What it did was establish a durable architecture capable of carrying a nation’s debates across mountains, rivers, and generations.

In retrospect, the law’s genius lies in its humility. It did not attempt to control content. It did not prescribe orthodoxy. It built routes and protected seals. It trusted that citizens, given access to information, would argue, reason, and decide.

There is something almost old-fashioned about that confidence. It assumes that liberty requires circulation rather than censorship, that disagreement is evidence of vitality rather than decay, and that unity grows from connection rather than coercion.

The post roads designated in 1792 stretched from Maine to Georgia and into the western territories. They stitched together a republic that might otherwise have frayed. They carried newspapers that fueled political parties, letters that maintained family bonds, and commercial notices that supported economic growth.

They also carried the burdens of partisanship and the weight of controversy.

Institutions rarely achieve purity. They achieve endurance.

The Postal Act endures in spirit because it grounded communication in constitutional authority, civic purpose, and legal protection. It recognized that a nation is not merely a collection of laws but a network of conversations.

When Washington signed the Act, he could not have foreseen every transformation it would undergo. But he and his contemporaries understood the stakes. Without dependable communication, the United States risked fragmentation. With it, the republic had a chance to mature.

The nervous system they constructed did more than transmit messages. It transmitted membership.

And that may be the most profound achievement of all.

Leave a comment