Segment 1 – The Bookseller Who Saw What Others Missed

There is a habit we fall into when we talk about the American Revolution. We compress it. We reduce it. We flatten it into a handful of marble statues and powdered wigs. Washington stands here. Jefferson stands there. Adams shouts in the corner. And somewhere in the background, a cannon goes off as if by magic.

But cannons do not move themselves.

If you rewind to November of 1775, what you find is not a polished army on the brink of triumph. What you find is a nervous, half-formed experiment. George Washington has only recently taken command of what we now call the Continental Army. In reality, it is a loose collection of militias with expiring enlistments and itchy feet. Men are going home. Regiments are thinning. Connecticut units, in particular, are peeling away as winter approaches. Washington knows he needs twenty thousand soldiers. He has perhaps eight thousand. Of those, maybe five thousand are ready for real combat.

And yet, somehow, he has the British bottled up inside Boston.

After Bunker Hill, the British occupy the city. The Continental forces surround it. It is a stalemate carved in cold wind and suspicion. The British are secure behind water and fortifications, but they are increasingly short on supplies. The Americans hold the countryside and the high ground, but they lack what matters most in siege warfare: heavy artillery.

They have muskets. They have courage. They have anger. What they do not have are the guns to force a fleet out of harbor.

What The Frock – The Musical

So Washington considers what desperate men consider. He calls a war council and floats a bold idea: a direct assault. Cross the Mystic. March through Charlestown. Smash into Boston and end it in one violent stroke.

His generals stare at him as though he has proposed charging a stone wall with spoons. They tell him, respectfully but firmly, that it is a terrible plan. They do not have the manpower. They do not have the artillery. They would be slaughtered.

And that is when the quiet solution begins to form.

The guns exist. They are just not in Boston.

Months earlier, Fort Ticonderoga had fallen into American hands in a dramatic but almost absurd fashion. Ethan Allen and Benedict Arnold took it from a groggy British garrison in upstate New York. The fort contained what Washington desperately needed: cannon, mortars, powder, iron, brass. The tools of siege warfare.

The problem was distance. Nearly three hundred miles of it. Mountains. Rivers. Forest. And winter.

Enter Henry Knox.

He is not one of the marble statues. He is not yet thirty. In fact, he is twenty-five. He has no formal military education. He did not attend a European academy. He did not inherit rank.

He left school at nine years old.

His father, a shipbuilder, ran into financial trouble and vanished to the West Indies, leaving young Henry behind. The boy went to work as a clerk in a bookstore. And there, in the quiet among the bindings and dust, something extraordinary happened.

He read. He read everything.

He taught himself Greek and Latin. He devoured Plutarch’s Lives and Caesar’s Commentaries. He studied Tacitus. He absorbed the architecture of Roman campaigns and the logic of siege warfare. He learned French. He discussed military theory with British officers who frequented Boston’s shops. In 1771, he opened his own store, the London Book Store, which became something of an intellectual crossroads.

He did not merely sell books. He used them.

He joined the Ancient and Honorable Artillery Company of Massachusetts, a militia organization devoted to the science of artillery. There, under British instruction, he learned the mechanics of guns: elevation, recoil, trajectory, powder measurement, fortification geometry. It was, in effect, an informal academy. He was barely in his mid-teens.

By the time unrest in Boston hardened into rebellion, Knox stood in the middle of events. He witnessed the Boston Massacre. He testified afterward. He married Lucy Flucker, daughter of a Loyalist official, and together they chose the revolutionary cause over family comfort. When the siege of Boston began after Lexington and Concord, they fled the city. His sword was reportedly sewn into Lucy’s coat to keep British soldiers from confiscating it.

Knox was not a casual patriot. He was all in.

Washington noticed him.

When Washington arrived in Cambridge in July 1775 to assume command, he found fortifications under construction and a large, energetic young man overseeing much of the engineering effort. Knox was impossible to miss physically. He stood six feet three inches tall and weighed close to three hundred pounds. He was affable, intelligent, quick with humor, and deeply serious about his work. He impressed Washington not merely with enthusiasm, but with competence.

So when the question arose, how do we get artillery?, Knox offered an answer that must have sounded almost reckless.

“I can bring the guns from Ticonderoga.”

Washington looked at the calendar. It was November.

Winter in New England is not a suggestion. It is a verdict.

But Knox had already thought this through. As an engineer, he understood something critical: if you were ever going to move sixty tons of iron across rivers and mountains with primitive infrastructure, winter might actually be your only chance. Frozen ground is firm. Snow can support sleds. Ice can become a bridge if handled correctly.

In other words, what most men would call an obstacle, Knox called an opportunity.

Washington authorized the mission. No trouble or expense was to be spared.

Knox set out on horseback for Fort Ticonderoga and arrived on December 5, 1775.

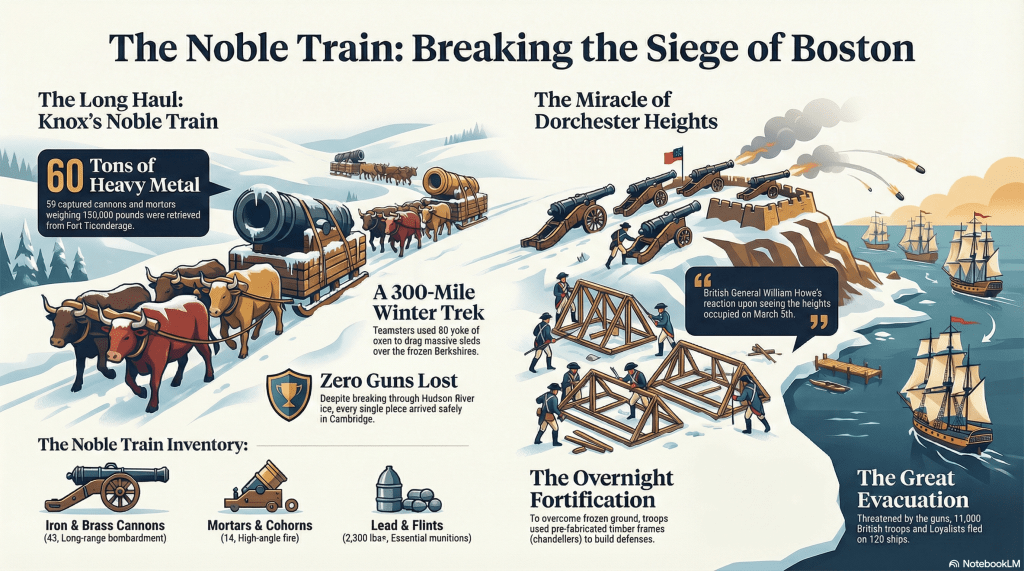

The fort sat quiet and cold in upstate New York. The captured guns had been largely untouched since their seizure. Knox immediately began inventorying what he would take. He selected fifty-nine pieces of artillery. Cannons ranging from four-pounders to massive twenty-four-pounders. Eight mortars. Six cohorns, portable mortars used for lobbing explosive shells. Two howitzers. In total, roughly 120,000 pounds of metal. Sixty tons.

Alongside the guns came thousands of pounds of lead and tens of thousands of gunflints.

In a letter to Washington, Knox referred to what he was assembling as a “noble train of artillery.” The phrase was optimistic. It was also accurate. This was not a handful of field pieces. It was a siege arsenal.

Now came the real question: how to move it.

The first leg would be by water. The guns were dismantled and loaded onto flat-bottomed boats, gondolas, scows, bateaux, and sent down Lake George before the ice could claim it. One heavily loaded boat sank in shallow water. It was bailed out, refloated, and reloaded. Nothing was left behind.

At the southern end of the lake, the expedition shifted to sleds. Knox hired local teamsters. Forty-two sleds were procured. Dozens of teams of oxen and horses were assembled, sometimes through persuasion, sometimes through negotiation, sometimes through sheer insistence. General Philip Schuyler assisted in securing animals when negotiations stalled.

Then the long pull began.

The Berkshire Mountains do not care about your political ideals. They are steep, cold, and indifferent. Snowstorms lashed the convoy. Ropes snapped. Runners cracked. Men cursed. Knox, massive and energetic, moved constantly among them, adjusting loads, calculating angles, encouraging persistence.

From high ridges he wrote of views so expansive one might “almost see all the kingdoms of the Earth.” It was poetic, but also revealing. Knox understood the scale of what they were doing. This was not a mere supply run. This was the hinge of a campaign.

The Hudson River posed the greatest challenge. It was frozen, but not reliably so. Beneath the ice, water continued to move. A miscalculation could swallow a cannon whole.

Here the bookseller-engineer revealed his quiet brilliance. He ordered holes cut into the ice. Because water beneath ice is pressurized, it rose through the openings and flooded the surface. In the freezing air, that water solidified, thickening the ice sheet. The river became stronger, layer by layer.

Even so, disaster nearly struck. An eighteen-pounder broke through and sank. Local citizens, summoned with ropes and manpower, hauled it back from the riverbed. It was not abandoned. Nothing was.

Knox had initially estimated the journey might take sixteen or seventeen days. It took closer to forty.

By late January 1776, the noble train reached Cambridge.

Every gun arrived. Not one lost.

Washington now possessed the artillery he needed. The question that remained was where and how to use it.

And that is where the story turns from endurance to strategy.

When the guns finally rolled into Cambridge in late January of 1776, they did not arrive with trumpets or banners. They arrived caked in frost, rope-burned, scarred from ice and stone, hauled by men who looked as though winter itself had tried to claim them and failed.

Henry Knox had done the impossible thing quietly. Forty days. Nearly three hundred miles. Fifty-nine pieces of artillery. Sixty tons of iron and brass dragged across mountains and rivers in the worst season New England could offer.

But here is the truth history rarely admits: logistics is only the first half of victory. Placement is the second.

Washington now had guns. What he did not have was a way to use them.

Boston in early 1776 is not the Boston of modern maps. Much of what we know today as filled land did not exist. The harbor was narrower, more defined, its approaches more obvious. To the south of the town rose a position known as Dorchester Heights. Whoever controlled that ground controlled the harbor. Whoever controlled the harbor controlled the fleet. And whoever controlled the fleet controlled Boston.

It was obvious in hindsight. It was not simple in practice.

The problem was frozen earth.

You cannot dig into January in Massachusetts. The ground becomes stone. Traditional siege practice requires entrenchments, redoubts, gun pits. Knox and Washington had artillery, but they could not simply carve out emplacements the way European armies might in warmer seasons.

So they would not dig down.

They would build up.

Washington and his engineers, including Rufus Putnam, devised a plan that required audacity, silence, and coordination at a scale the Continental Army had not yet demonstrated. On the night of March 4, 1776, they would move the guns to Dorchester Heights under cover of darkness and construct fortifications above ground before the British realized what had happened.

It was a gamble of engineering and nerve.

The guns first had to be moved from Cambridge into position. That meant teams of men and animals hauling iron through snow and darkness without clatter or chaos. To mask the sound, American batteries elsewhere began intermittent bombardment of British positions. Nothing heavy enough to provoke a full response. Just enough noise to cover movement.

Meanwhile, nearly three thousand men ascended the Heights in disciplined silence.

They carried not just cannon, but prefabricated materials. Barrels. Timber. Fascines—bundles of sticks bound tightly together. Hay bales. Tools. Everything needed to build a defensive position on top of frozen ground.

All night they worked.

Instead of digging into the earth, they constructed breastworks above it. Barrels were filled with earth and stacked. Timber frames were erected and reinforced. Hay and brush absorbed impact. Gun platforms were assembled and leveled.

Knox supervised placement carefully. Artillery is not decoration. Each piece has a range, an arc, a purpose. The twenty-four-pounders commanded the harbor approaches. Mortars were positioned to lob shells into the town and toward British concentrations. Elevation and sight lines were measured by eye and experience.

They were not improvising blindly. They were applying the mathematics Knox had absorbed as a boy reading Roman campaigns in a Boston bookstore.

By dawn, the impossible had happened again.

General William Howe awoke to find the skyline altered.

Where the night before there had been bare ground, now stood fortifications bristling with guns aimed directly at the British fleet and the town below. Knox’s noble train had become a loaded threat.

Howe reportedly stared through his glass and exclaimed that the rebels had accomplished more in a single night than his own army could in three months.

That was not merely admiration. It was recognition of peril.

The British fleet in Boston Harbor was now vulnerable. Ships at anchor are formidable, but not invincible. From Dorchester Heights, American artillery could rake decks, shatter masts, ignite chaos. The British army inside the town was effectively pinned between fortified heights and open water.

Howe was not without options. The obvious one was to storm the Heights.

He had tried something similar at Bunker Hill the previous June. It had succeeded, in June, at least technically. The British took the ground. But they paid for it in blood. Charging fortified positions uphill against determined defenders is an expensive habit.

Still, he began preparing for an assault.

And then New England intervened.

On the very day the British were to move, a violent nor’easter roared through Boston. Snow and wind lashed the harbor. Ships strained at anchor. Visibility collapsed. Any coordinated attack became impossible.

The storm did not decide the campaign alone, but it removed Howe’s final practical chance at reclaiming the Heights before the American fortifications hardened.

When the skies cleared, the British faced a simple calculation. Stay, and risk destruction of the fleet. Attack, and risk another Bunker Hill with uncertain outcome. Leave, and preserve the army for future operations.

On March 17, 1776, they chose departure.

Thousands of British troops, along with Loyalist civilians who feared remaining under Patriot control, boarded ships and sailed for Halifax, Nova Scotia. Boston was evacuated. The siege ended not with a climactic assault, but with a strategic repositioning forced by artillery and geometry.

The Continental Army had won its first major strategic victory.

Consider what did not happen.

There was no catastrophic charge across open ground. No suicidal rush through Boston’s streets. No desperate gamble that might have broken the fragile army Washington was trying to build. Instead, there was planning. Engineering. Movement. Placement.

There was Henry Knox.

It is tempting to say that Washington won Boston. He commanded the army, after all. But leadership depends on tools. Without heavy artillery, Dorchester Heights would have been symbolic at best. With artillery, it became decisive.

The guns did not fire in massed fury. They did not have to. Their presence altered the equation.

War is often described as the clash of armies. Just as often, it is the manipulation of leverage.

Knox provided leverage.

The significance of Boston’s evacuation rippled outward. For the first time, American forces had compelled the British to abandon a major city. Morale soared. Confidence hardened. The Continental Army, which only months earlier had been a loose assembly of militias with expiring enlistments, now possessed proof that disciplined action could produce results.

Washington himself gained something priceless: credibility.

And Knox’s stature rose with it.

He was promoted and formally appointed chief of artillery. He would not remain a logistical footnote. At Trenton later that year, he would play a crucial role in ferrying guns across the ice-choked Delaware River. The famous crossing that lives in paintings did not succeed by romance alone. It succeeded because artillery moved with the infantry, because Knox calculated weight, ice strength, current, and landing points.

At Monmouth, he directed guns under brutal heat. At Yorktown, his artillery would help seal Cornwallis’s fate.

But in March of 1776, none of that was guaranteed.

What was guaranteed was this: without artillery, the siege of Boston might have collapsed into a disastrous assault or a slow, demoralizing stalemate. With artillery, placed correctly, the British position became untenable.

Boston never again fell under British occupation during the war.

There is a deeper lesson here, one less romantic but more enduring. Revolutions are not sustained by speeches alone. They are sustained by supply chains, by carpenters, by engineers, by men who understand that an idea must sometimes be hauled uphill in the dark and set in iron.

Henry Knox was twenty-five years old when Washington entrusted him with sixty tons of metal and the future of a campaign.

He did not see winter as an excuse. He saw it as an advantage.

He did not see rivers as barriers. He saw them as problems to be solved.

And when dawn came on March 5 and British officers squinted at guns that had not existed the night before, they were not looking at luck. They were looking at applied intellect.

The noble train had arrived. The mathematics had been calculated. The angle of war had shifted.

And Boston was no longer safe for the Crown.

Evacuation Day in Boston, March 17, 1776, was not the end of anything. It was the beginning of proof.

Proof that the Continental Army could execute a complex operation. Proof that Washington could think beyond impulse. Proof that logistics, handled by the right hands, could bend an empire.

The British departure from Boston was not a battlefield spectacle. There were no dramatic cavalry charges, no bayonet duels in narrow streets. The redcoats boarded ships. Loyalists followed, many never to return. The fleet turned north toward Halifax. The harbor emptied.

Boston never again fell under British occupation during the war.

And standing somewhere in the background of that victory was Henry Knox, a bookseller who had taught himself war.

He did not linger in Boston to bask in applause. There was no time for that. The war was widening. The British would regroup. New York loomed as the next target. The struggle was not ending, it was escalating.

Washington now faced a different kind of campaign. Boston had been a siege, a standoff. What was coming would be fluid, dangerous, unpredictable. He needed artillery that could move with him, not sit on a single height overlooking a harbor.

He needed Knox.

Knox was formally appointed chief of artillery for the Continental Army. It was not a ceremonial title. The American artillery arm was a patchwork at best. Guns of different calibers. Ammunition inconsistencies. Powder shortages. Crews with uneven training. Knox set about standardizing, organizing, professionalizing.

He had never attended a military academy, yet he built the foundations of one in spirit. He drilled crews. He refined placement doctrine. He calculated ranges. He integrated artillery into battlefield maneuver rather than treating it as ornamental thunder.

Later that same year, as Washington faced disaster in New York and retreated across New Jersey, Knox again became essential.

The Delaware River in December of 1776 was a living obstacle. Ice floes churned in black water. Wind cut through wool and bone. Washington’s army was battered and shrinking. Morale was fragile. Enlistments were again expiring.

The crossing that Americans now memorialize in paintings required more than courage. It required calculation. Boats had to bear weight. Ice had to be judged. Artillery had to be ferried across without capsizing or being lost to the current.

Knox oversaw the movement of the guns.

It is one thing to move men across a frozen river. It is another to move iron.

The attack on Trenton that followed depended in no small part on artillery positioned with precision in narrow streets. The guns sealed escape routes, shattered resistance, amplified shock. Victory at Trenton reignited a cause that had been sputtering.

Again, Knox did not claim the spotlight.

At Monmouth in 1778, under punishing summer heat, he directed artillery fire that stabilized American lines during a chaotic engagement. At Yorktown in 1781, when the war’s final act unfolded, artillery would once again decide matters. The systematic pounding of British defenses, the carefully constructed parallels and batteries, the relentless narrowing of Cornwallis’s options all bore the imprint of artillery science.

Knox had read Caesar. Now he was living him.

After Yorktown, the war did not end immediately, but its outcome had shifted decisively. The Treaty of Paris would follow. Independence would be recognized. The fragile experiment would move from rebellion to governance.

And here again, Knox would step into a role few remember.

When the new United States began constructing its federal government under the Constitution, the question arose, who would build the military establishment of the republic?

Washington, now President, turned to someone he trusted implicitly.

Henry Knox became the first Secretary of War of the United States.

Imagine the scale of that task. There was no standing army worthy of the name. There was no permanent administrative framework. There were frontier conflicts to manage, arsenals to establish, coastal defenses to consider, naval questions to answer.

Knox helped design the early structure of the American military. He oversaw policies related to fortifications and armaments. He laid groundwork for what would eventually become the Military Academy system. He supported naval construction, including early ships that would grow into the small but determined fleet of the young republic. The USS Constitution, launched in the 1790s, sailed in a navy Knox had helped shape.

He was also a founding member of the Society of the Cincinnati, an organization of Revolutionary officers that emphasized a striking principle. Like the Roman hero Cincinnatus, a citizen soldier should return to private life after serving the republic. Power was not to be hoarded.

That idea mattered. It mattered that Washington stepped down. It mattered that officers did not transform victory into dictatorship. Knox believed in that restraint.

Not every chapter of his postwar life glowed.

He invested heavily in land and industry in what would become Maine. Ambition outran profit. Financial troubles mounted. Ventures faltered. The hero of logistics struggled with peacetime economics. It is a reminder that competence in war does not automatically translate into commercial success.

And then, in 1806, an almost absurd end.

At fifty six years old, Henry Knox was eating dinner at his home in Thomaston when he accidentally swallowed a chicken bone. The injury led to infection. Infection, in an age before antibiotics, could be fatal.

The man who had survived ice rivers, mountain crossings, battlefield chaos, and the birth of a nation died from a simple domestic accident.

History has a dry sense of humor.

His name lingers in places. Knox counties. Knox trails across Massachusetts and the Berkshires marking the path of the noble train. There is Fort Knox in Kentucky, though historians still debate whether the name honors him directly. Roads wind through New England bearing his memory. The Ancient and Honorable Artillery Company still exists in Massachusetts, tracing a lineage that includes him.

But he does not dominate textbooks.

Why?

Perhaps because he does not fit the neat categories we prefer. He was not the principal political theorist. He did not draft the Declaration. He was not the towering commander in chief. He was something less glamorous and more essential.

He was the man who made ideas practical.

There is a tendency in popular history to compress revolutions into rhetoric. We quote Jefferson’s grievances. We celebrate Adams’s defiance. We admire Washington’s composure.

All of that deserves admiration.

But none of it functions without someone moving the guns.

When Jefferson later wrote that the king was waging war against the colonies, he was describing a conflict of arms as well as ideas. War requires organization. It requires supply. It requires understanding terrain, weight, distance, weather.

Without Knox, the siege of Boston might have collapsed into a disastrous frontal assault. Without Knox, Trenton might have lacked the artillery punch that made it decisive. Without Knox’s administrative work, the early republic might have stumbled in organizing its defense.

He was, in many respects, Washington’s right hand.

There was a moment during the radio discussion that sparked this episode when a caller suggested that only a handful of men truly did anything in the Revolution. It is a common view. We gravitate toward a small cast of heroes because it simplifies the narrative.

But the Revolution was not won by three or four men.

It was won by networks of competence.

By sergeants who held lines. By carpenters who built fortifications. By farmers who lent oxen. By local citizens who hauled an eighteen pounder from the bottom of the Hudson River because they refused to let it sink into obscurity.

And by a twenty five year old bookseller who understood that winter was not an enemy, but a tool.

There is something bracing about that.

In an age that often underestimates youth and overestimates credentials, Henry Knox reminds us that disciplined self education can produce mastery. In a culture that often celebrates noise over substance, he reminds us that quiet execution changes outcomes. In a time when logistics is taken for granted because delivery trucks arrive on schedule, he reminds us that supply chains can determine destiny.

He did not write the Declaration. He made it possible.

The noble train of artillery was not just a convoy of guns. It was an argument in iron. It declared that the colonies were capable of coordinated, sustained, strategic action. It signaled that this was not a riot. It was a war conducted with increasing professionalism.

And when the British ships sailed out of Boston Harbor under gray skies in March of 1776, they were not merely retreating from a city.

They were retreating from the realization that the Americans had learned how to fight.

Henry Knox helped teach them.

Leave a comment