The Declaration of Independence reads like a legal indictment. It is careful. It is structured. It lays out charges as if a verdict were inevitable and only the record needed to be completed.

Common Sense sounds nothing like that.

It sounds like a street argument. A tavern argument. A challenge thrown across a table with a mug between two hands and a fire burning low. It is blunt. It is impatient. It does not bother with procedural language. It asks a more dangerous question long before Jefferson ever picks up his pen.

They are saying the same thing.

But they are saying it in different registers, to different audiences, at different stages of realization.

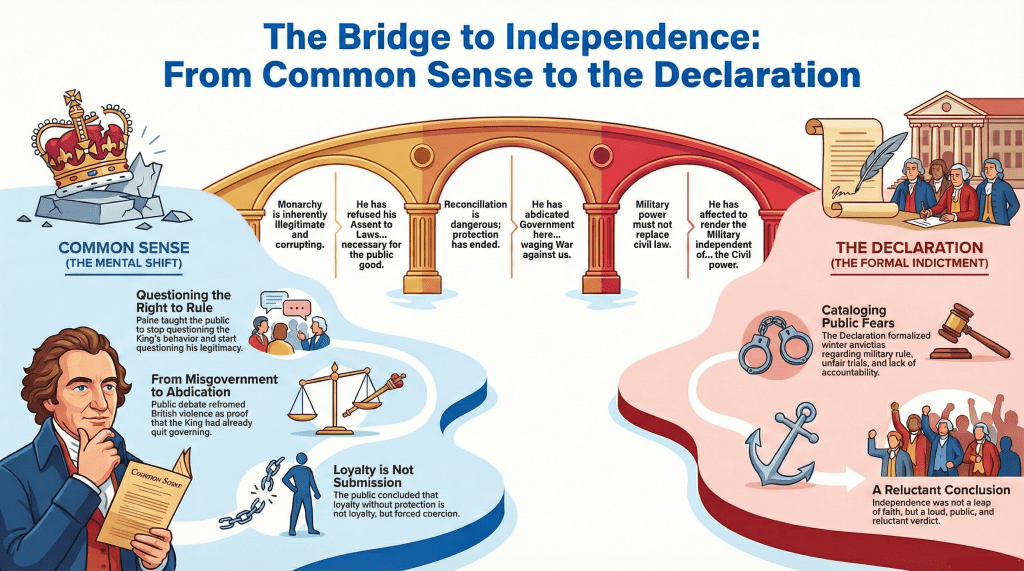

The mistake we often make is to treat Common Sense as a warm up act and the Declaration as the main event. Pauline Maier warns against this. What Paine does in January is not to introduce grievances. Those already exist. He does something far more destabilizing. He teaches Americans to question legitimacy itself.

Before Americans accuse the King of abuses, they first question whether he has any right to rule at all.

That is the ground Paine clears in January 1776.

Before Common Sense, most political arguments in the colonies still assume monarchy as a given. Parliament may be overreaching. Ministers may be corrupt. Policies may be unjust. But the structure itself is rarely challenged. The King is criticized as a bad ruler, not as an unnecessary one.

Paine refuses that distinction.

He does not ask whether George III governs poorly. He asks why anyone governs by inheritance at all. He describes monarchy not as a tradition, but as an artificial contrivance that benefits a few at the expense of the many. He attacks the idea of kingship as something fundamentally at odds with natural order and moral reason.

This is where modern readers sometimes misunderstand Paine. They see bombast. They see provocation. They miss the strategic brilliance of his timing.

By January 1776, blood has already been spilled. Cities are occupied. Trade is strangled. Trust is broken. Many Americans already feel that something is deeply wrong, but they are still framing the problem as misconduct within a legitimate system.

Paine gives them a new frame.

If monarchy itself is illegitimate, then abuses are not aberrations. They are symptoms.

This matters because it flips the burden of explanation. Instead of asking why the King has done harmful things, Americans begin asking by what right he does anything at all. That shift is subtle but irreversible.

Once legitimacy is questioned, grievances stop being complaints and become evidence.

This is why the Declaration begins where it does. It does not open with taxes. It does not open with troops. It opens with authority. It opens with the claim that governments exist to secure rights and derive their powers from consent. That language is not decorative. It is prosecutorial.

When Jefferson writes, “He has refused his Assent to Laws, the most wholesome and necessary for the public good,” he is not merely accusing the King of stubbornness. He is asserting that lawful authority has failed at its most basic function.

When Jefferson writes, “He has dissolved Representative Houses repeatedly,” he is not lamenting inconvenience. He is describing the systematic destruction of political legitimacy itself.

These are not just complaints about bad behavior. They assume a prior conclusion. Authority has already failed.

That conclusion did not originate in the drafting committee in June. It originated in public debate in January.

Paine’s genius is not that he invents the case against the King. It is that he teaches ordinary people how to think about power without reference to tradition. He strips away habit and asks Americans to evaluate monarchy as if it were new and strange.

What purpose does it serve. What moral claim does it have. Why should obedience be automatic.

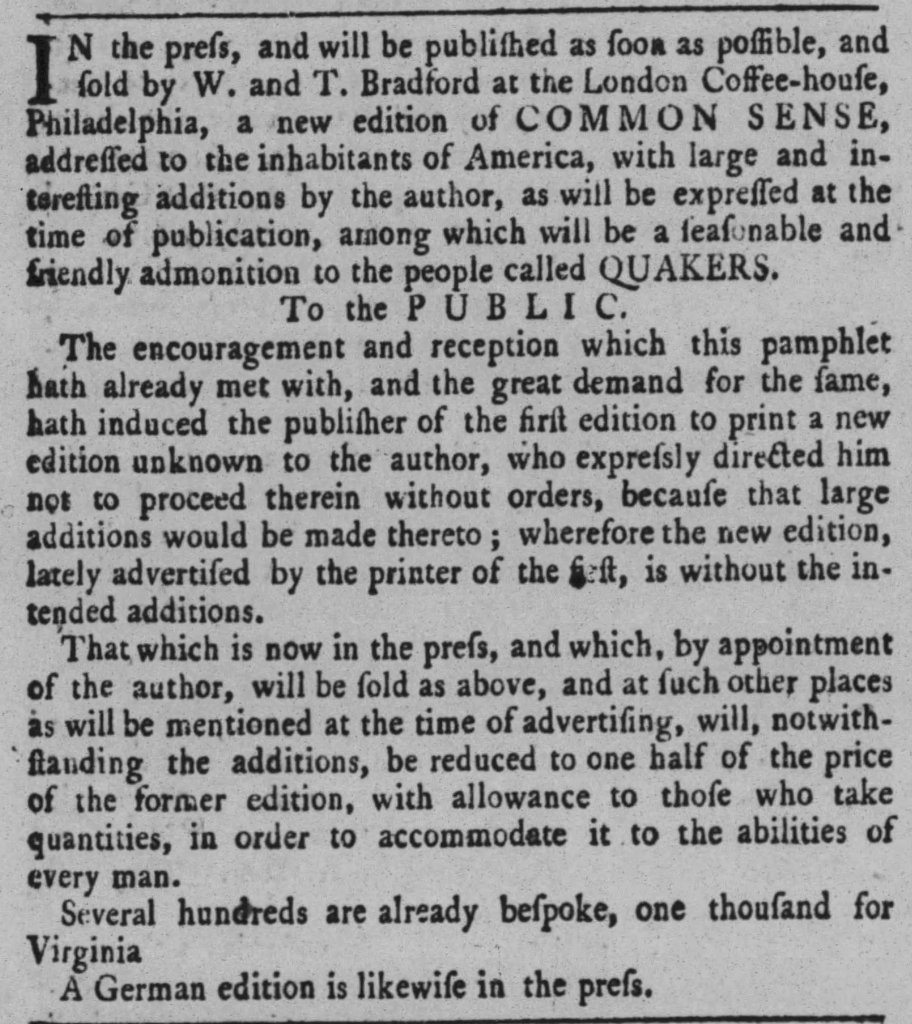

These questions do not require elite education to answer. That is why Common Sense spreads so quickly. It is not read quietly. It is read aloud. It is argued over. It is repeated imperfectly. It moves through taverns, churches, workshops, and militia camps. It becomes part of the air people breathe.

And once that air changes, Congress cannot pretend nothing has happened.

This is where the Declaration’s grievance list begins to take on a different character. Read after Common Sense, the grievances do not feel like the opening of a debate. They feel like the closing argument.

The King has refused assent to laws. He has obstructed justice. He has dissolved assemblies. He has kept standing armies without consent. He has rendered the military independent of civil power.

These are not random offenses. They are cumulative proof that legitimate authority no longer exists.

Paine prepares Americans to hear these charges not as unfortunate errors, but as confirmation of a deeper truth. If monarchy is artificial and corrupting, then these outcomes are inevitable. If authority rests on inheritance rather than consent, then it will eventually rule against the people rather than for them.

This is why Paine’s most important lesson is not about independence. It is about questioning the source of power.

He teaches the public to stop asking, “Why has the King done this,” and start asking, “By what right does he do anything at all.”

That is a revolutionary move, not because it leads to rebellion, but because it leads to clarity. Once that question is asked honestly, reconciliation becomes impossible. Reform becomes meaningless. The argument is no longer about policy. It is about whether the system itself deserves to continue.

At that point, the grievance list becomes inevitable.

This is also why the Declaration does not bother to argue that Britain could be better. It argues that Britain has already failed. The King is accused not merely of tyranny, but of abdication. He has withdrawn protection. He has waged war against his own subjects. He has abandoned the moral basis of rule.

Those conclusions were not reached overnight. They were rehearsed all winter long.

By the end of January 1776, Americans are no longer tallying offenses one by one and hoping for correction. They are questioning legitimacy itself. They are asking whether authority that behaves this way has any claim to obedience.

The Declaration will simply formalize that verdict.

What Paine does is strip away the last emotional attachment to monarchy. He does not need to persuade Americans to be angry. They already are. He persuades them that anger is justified because the structure they are confronting is fundamentally flawed.

Once that realization takes hold, the rest follows with grim logic.

You do not petition an illegitimate authority.

You do not reconcile with an abdicated one.

You document it.

You charge it.

You move on.

That is the arc from Common Sense to the Declaration’s grievances. It is not a leap. It is a progression.

And it begins not with a list of abuses, but with the collapse of belief.

By the time Jefferson writes, the verdict is already in. The people have reached it themselves, in cold rooms, over shared pamphlets, arguing not about taxes or laws, but about whether kingship itself ever made sense to begin with.

That is why the Declaration sounds so final.

It is not the start of the argument.

It is the moment the argument ends.

From Reconciliation to Abdication

The Declaration never says the King misgoverned.

That omission matters.

It does not argue that George III ruled badly, clumsily, or even cruelly. It makes a more devastating claim. It says he abdicated government. That word is not rhetorical flourish. It is a conclusion. And it did not originate in Philadelphia in July. It rose out of the winter debates that followed Common Sense, when Americans began to realize that what they were facing was not failed leadership but the collapse of governance itself.

In ordinary political language, abdication implies departure. A ruler steps aside. Authority is relinquished. But in the American understanding of early 1776, abdication takes on a darker meaning. It does not describe withdrawal alone. It describes replacement. Law is replaced by force. Protection is replaced by punishment. Relationship is replaced by coercion.

This is the shift that makes reconciliation not merely improbable, but dangerous.

Paine presses this argument relentlessly. He insists that reconciliation is not a middle path or a cautious pause. It is a refusal to recognize reality. By clinging to the hope of repair, Americans risk misreading violence as negotiation and submission as prudence. His warning lands because it aligns with what people are already experiencing.

By February 1776, British policy no longer looks like governance to many colonists. It looks like war waged against communities rather than authority exercised over them.

That perception is crucial, because it reframes every British action that follows. When towns are shelled, ports blockaded, or trade strangled, these are no longer measures of control within a political relationship. They are acts of hostility against an enemy population.

The Declaration captures this realization with startling clarity when it states, “He has abdicated Government here, by declaring us out of his Protection and waging War against us.”

That sentence is not an accusation of excess. It is an assertion of absence. Protection is the defining obligation of government. Once it is withdrawn, what remains is power without purpose.

The next grievance follows naturally. “He has plundered our seas, ravaged our coasts, burnt our towns, and destroyed the lives of our people.” These are not framed as unfortunate byproducts of restoring order. They are presented as proof that order itself has been abandoned.

Paine teaches Americans how to see these acts not as enforcement, but as evidence. If the Crown wages war on its subjects, it is no longer acting as a government. It has crossed a threshold from authority into occupation.

This idea circulates rapidly in public discussion. In taverns and town meetings, the language grows sharper. People begin to speak less about loyalty and more about protection. Less about rights and more about survival. The old moral vocabulary no longer fits the facts on the ground.

Several arguments surface again and again in these conversations.

First, loyalty without protection is not loyalty at all. It is submission. Allegiance, Americans argue, is reciprocal. It assumes mutual obligation. When one side withdraws protection and applies violence, the bond dissolves.

Second, force has replaced law. Decisions are no longer mediated through assemblies, courts, or petitions. They arrive on ships and with regiments. Once coercion becomes the primary instrument, governance has ceased to function.

Third, reconciliation becomes a delaying tactic rather than a solution. Calls for patience are interpreted as avoidance of responsibility. Each appeal to wait only postpones the acknowledgment that the relationship itself has ended.

This is why Paine’s argument cuts so deeply. He does not tell Americans that reconciliation has failed. He tells them that it is actively blinding them. It prevents them from acting in accordance with the reality they are already living under.

By late winter, this view is no longer confined to radicals. It spreads precisely because it explains what people are seeing. The King’s actions are no longer debated as mistakes. They are interpreted as confirmation that the imperial relationship has collapsed.

The Declaration reflects this shift perfectly. Its language does not plead. It declares. It does not ask for redress. It records a conclusion. The grievance list reads less like a negotiation and more like a coroner’s report.

The King is not accused of tyranny alone. Tyranny implies continued rule. He is accused of quitting his role while continuing to exercise power. That contradiction is the heart of the charge. Authority without responsibility is no authority at all.

This is why the Declaration does not offer conditions for reconciliation. There is nothing left to reconcile. Abdication has already occurred. The document simply names it.

What is striking is how little debate remains by the time this language is written. The argument has already been settled at the local level. Congress is not dragging the colonies forward. It is catching up to them.

Months earlier, Americans had still hoped that violence might shock Britain back into reason. By February, many have concluded that violence is the policy. Once that realization takes hold, reform becomes meaningless. You do not reform an enemy. You respond to one.

This is the moment when independence becomes operational, even before it is declared. Communities reorganize authority. Oaths shift. Royal officials are ignored or removed. Decisions are made without reference to imperial approval. These are not symbolic gestures. They are practical adaptations to a perceived vacuum of legitimate power.

The Declaration’s use of the word abdicated simply codifies this reality. It gives formal language to an experience already lived.

By winter’s end, Americans are no longer asking what changes might restore harmony. They are describing a vacancy of authority. The old structure has not been damaged. It has been abandoned.

The King, in their view, has already left the building. The only question remaining is whether Americans will continue to pretend otherwise.

Segment Two ends here, not with defiance, but with recognition. Governance has ended. Protection has been withdrawn. What remains is force, and force alone cannot sustain legitimacy.

The Declaration does not create this conclusion. It testifies to it.

When Fear Turns Into Accusation

Here is what we forget.

The grievances are not written in confidence.

They are written in anxiety.

By the time the Declaration takes shape, Americans are no longer debating whether independence is desirable. That argument is already exhausted. What dominates the winter of 1776 is something far more unsettling. Fear. Not panic, not hysteria, but a steady, grinding apprehension about what happens when power no longer listens and force becomes normal.

This is the emotional temperature that modern readers often miss. The Declaration’s grievance list can sound theatrical when stripped of context, as if Jefferson were piling on accusations to justify a foregone conclusion. In reality, the grievances read the way anxious people talk when they are finally forced to be precise.

Winter 1776 is full of fears that now appear, almost verbatim, in legal language.

Fear of military rule.

Fear of justice severed from community judgment.

Fear of distance turned into a weapon rather than a boundary.

These are not abstractions. They are lived concerns debated in cold rooms by people who have already watched familiar institutions erode.

The grievance that the King “has affected to render the Military independent of and superior to the Civil power” reflects a deep unease that goes beyond opposition to troops. Americans do not fear soldiers simply because they are armed. They fear a world in which law no longer governs force. The presence of armies is alarming not because it threatens lives alone, but because it signals a reversal of order. When the military answers to authority outside the community, civil society becomes ornamental.

In the winter debates, this fear surfaces repeatedly. People ask what happens when soldiers enforce policy rather than law. What happens when obedience is extracted rather than consent given. What happens when commands replace judgments.

The grievance is not about uniforms in the street. It is about a future in which civic life survives only at the pleasure of armed power.

Another fear cuts just as deeply. The grievance condemning the practice of transporting Americans beyond seas to be tried for pretended offenses captures anxiety about more than legal inconvenience. It expresses terror at the removal of judgment from community.

Justice, as Americans understood it, was local by necessity. It relied on shared norms, witnesses, juries drawn from neighbors. Distance destroys that system. When trials are moved across an ocean, accountability evaporates. Authority becomes untouchable. The accused becomes isolated.

In winter conversations, this issue resonates powerfully. People worry about what happens when accusation replaces process. When guilt is determined far away by officials who neither know the community nor answer to it. Transportation for trial is feared not simply as punishment, but as erasure. A person disappears into a system that does not recognize them.

The grievance about taxation without consent also takes on sharper meaning in this climate. It is not merely a complaint about money. It is an expression of fear that obligation will be imposed without voice, that burdens will be assigned without representation, that extraction will replace participation.

Taken together, these grievances reveal a single underlying concern. That Americans will be ruled as subjects rather than citizens.

This distinction matters enormously. Subjects obey. Citizens consent. Subjects are managed. Citizens participate. The winter of 1776 is filled with anxiety that Americans are sliding irreversibly into the first category.

People worry openly about what kind of society will emerge if this trajectory continues. Will assemblies matter. Will courts matter. Will petitions matter. Or will all decisions flow from distant authority enforced by military presence.

Another fear complicates these discussions. The fear that liberty itself might dissolve into disorder.

This is where modern retellings often flatten the story. We imagine Americans confidently embracing self rule. In reality, many are deeply uncertain about their own capacity to govern. They fear mob rule. They fear the collapse of hierarchy. They fear debt repudiation, property seizures, social fragmentation.

The anxiety runs both ways. On one side is fear of coercion imposed from without. On the other is fear of chaos unleashed from within. The winter debates oscillate between these dangers, with no obvious safe harbor.

The Declaration’s grievance list captures this tension indirectly. It does not glorify rebellion. It does not celebrate upheaval. Its tone is defensive, almost somber. It reads like a justification offered reluctantly, not a manifesto proclaimed joyfully.

That tone reflects the emotional reality of the moment. Americans are not confident revolutionaries. They are anxious communities trying to articulate why familiar safeguards no longer function.

This is why the grievance list is not rhetorical excess. It is an answer to a season of public debate that demanded clarity.

Each grievance corresponds to a question people have already been asking out loud.

What happens when armies replace law.

What happens when justice is removed from the community.

What happens when distance shields authority from accountability.

What happens when consent is ignored.

What happens when obedience is demanded without protection.

The Declaration does not introduce these fears. It catalogs them.

It translates months of anxious conversation into a formal record. It takes what has been argued emotionally and renders it legally legible. That act alone marks a turning point. Anxiety becomes accusation. Fear becomes testimony.

This is also why the Declaration’s structure matters. It does not simply list grievances. It builds them. Each charge reinforces the sense that the problem is systemic rather than episodic. Taken together, they describe not misrule, but transformation. Governance has been replaced by domination.

The people who hear this document read aloud do not encounter new ideas. They recognize their own arguments reflected back at them with terrifying coherence.

This recognition matters because it resolves a lingering uncertainty. If the fears are accurate, then inaction is no longer prudence. It is surrender. If the pattern described in the grievances is real, then delay only deepens the danger.

By the time the Declaration circulates, Americans are no longer choosing between loyalty and independence. They are choosing between clarity and denial.

The Liberty 250 insight here is simple but uncomfortable. Independence was not born of confidence. It was born of fear disciplined into argument.

Common Sense taught Americans to stop hoping. It stripped away the comfort that reconciliation might rescue them from hard decisions. The Declaration taught them to testify. It demanded that those fears be named, organized, and placed on the record.

One removed illusion.

The other imposed responsibility.

Together, they show that independence was not a leap of faith. It was a conclusion reached reluctantly, loudly, and in public.

The Declaration does not shout victory.

It delivers testimony.

And in that testimony, the anxieties of winter become the charges of history.

Next Week – Knox Talks Stocks

Leave a comment