The story of the Black Codes is not a sidebar in Reconstruction. It is one of the load bearing beams, ugly, warped, and essential if one wants to understand why the building that followed looked the way it did.

The Black Codes emerged from a moment that felt, to many Americans in 1865, like standing in the aftermath of a storm that had flattened a town but spared the foundations. The Civil War had ended. The guns had cooled. The Union was preserved, at least on paper. Slavery was dead in law, even if its ghost had not yet figured that out. Four million formerly enslaved people stepped into freedom carrying little more than hope, memory, and the knowledge of how fragile both could be. White Southerners stepped into defeat carrying something else, fear, resentment, and an almost theological commitment to the old order.

The codes did not arrive as a single proclamation or a coordinated conspiracy. They arrived the way many systems of control do, piecemeal, bureaucratic, wrapped in legal language that pretended to be neutral. State legislatures across the former Confederacy moved with surprising speed in late 1865 and early 1866. Mississippi led the way, followed closely by South Carolina, Alabama, Louisiana, Florida, and others. Each state tailored its statutes to local conditions, but the pattern was unmistakable. Freedom would exist, but only on a short leash.

To understand why the Black Codes took the form they did, one has to grasp the panic that ran beneath the surface. The plantation economy had collapsed. Labor was suddenly negotiable. Land ownership remained overwhelmingly white. Political power was up for grabs. To many former slaveholders, this was not merely social disruption. It felt like an existential threat. If Black laborers could move freely, bargain wages, acquire land, vote, arm themselves, and testify in court, the entire hierarchy of Southern life would tilt, maybe collapse.

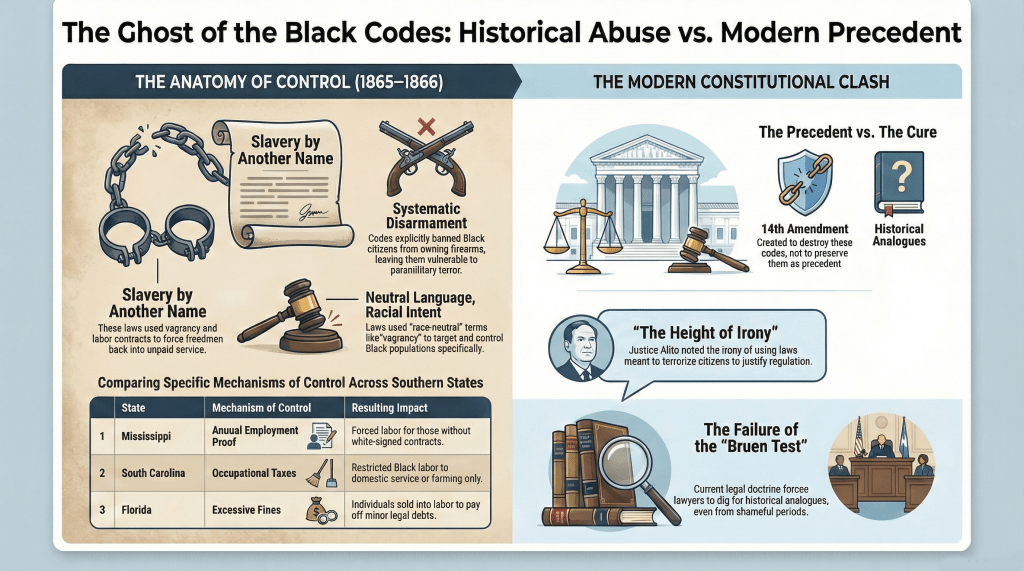

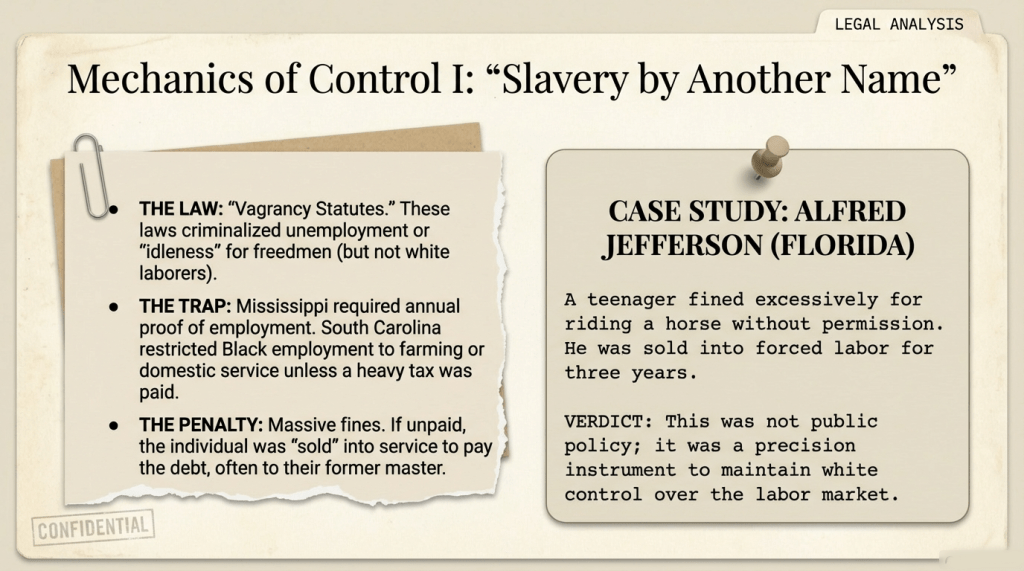

So the codes aimed not at restoring slavery outright, which would have violated federal law, but at reconstructing its functions. Labor control came first. Vagrancy laws became the blunt instrument of choice. Under these statutes, a Black person without proof of employment could be arrested, fined, and imprisoned. The definition of vagrancy was elastic enough to catch almost anyone who displeased local authorities. Fines were often set deliberately beyond reach. Failure to pay meant forced labor, leased out to private employers, frequently the same men who once owned them.

Mississippi required Black workers to carry written proof of employment for the coming year, contracts that effectively bound them to plantations under threat of arrest. South Carolina restricted Black labor to agriculture or domestic service unless a prohibitive tax was paid. Louisiana and Florida followed similar paths. These were not accidental outcomes. They were carefully calibrated systems designed to keep wages low, mobility restricted, and bargaining power nonexistent.

The law also reached into family life. Apprenticeship provisions allowed courts to seize Black children, especially those labeled orphans or whose parents were deemed vagrants, and bind them to white masters until adulthood. Consent was optional. Parental objection carried little weight. The stated goal was training and care. The lived reality looked far closer to involuntary servitude.

Civil rights were curtailed with equal enthusiasm. Black citizens were barred from serving on juries, holding public office, and in many cases voting at all. Testifying against white defendants was often prohibited. In courtrooms across the South, justice acquired a color line sharper than any drawn before the war.

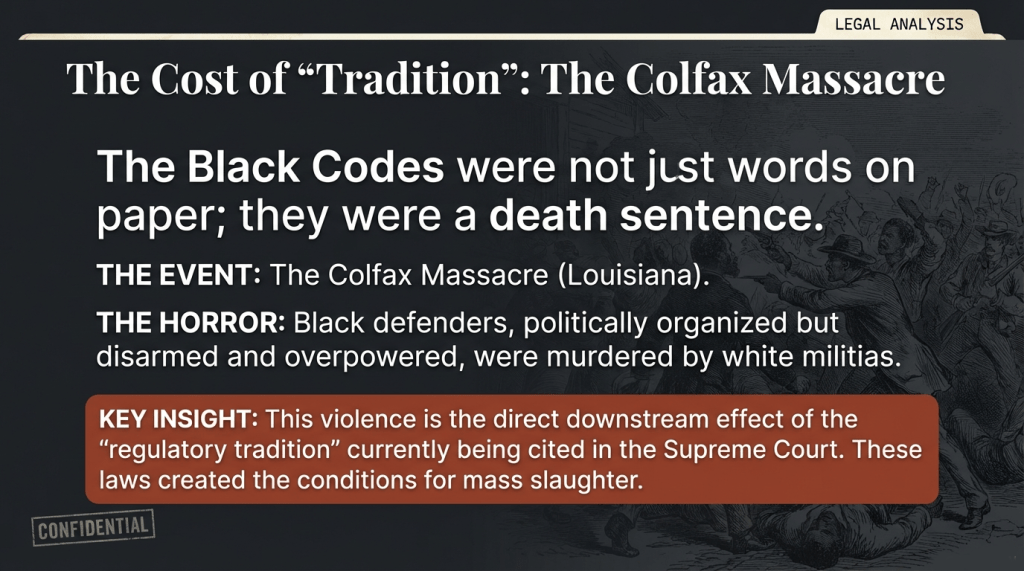

Disarmament deserves particular attention, not because it dominates modern debate, but because it reveals intent with unusual clarity. Several states explicitly forbade Black citizens from possessing firearms or ammunition without special permission. Mississippi required licenses issued by local authorities, the same authorities invested in keeping Black residents powerless. South Carolina followed suit. This was not about public safety in any modern sense. It was about vulnerability.

A disarmed population is easier to intimidate. White paramilitary groups understood this immediately. The Ku Klux Klan, White Leagues, and similar organizations did not arise in a vacuum. They flourished in an environment where Black self defense was illegal and white violence was rarely punished. Night rides, whippings, murders, and election day terror campaigns were not aberrations. They were enforcement mechanisms.

The human cost of these systems is best understood not through statistics but through individual stories, the kind that rarely make it into textbooks but linger in county records and newspaper clippings. In Florida, a Black teenager named Alfred Jefferson was fined an extraordinary sum for riding a horse without permission. Unable to pay, he was sold into labor for three years. His story was not unique. It was merely documented.

Convict leasing became the bridge between law and brutality. Arrests fed prisons. Prisons fed labor camps. Men convicted of vagrancy, minor theft, or fabricated offenses found themselves working in mines, on railroads, or back on plantations under conditions often worse than slavery. Mortality rates were staggering. Replacement was easy. The law ensured a steady supply.

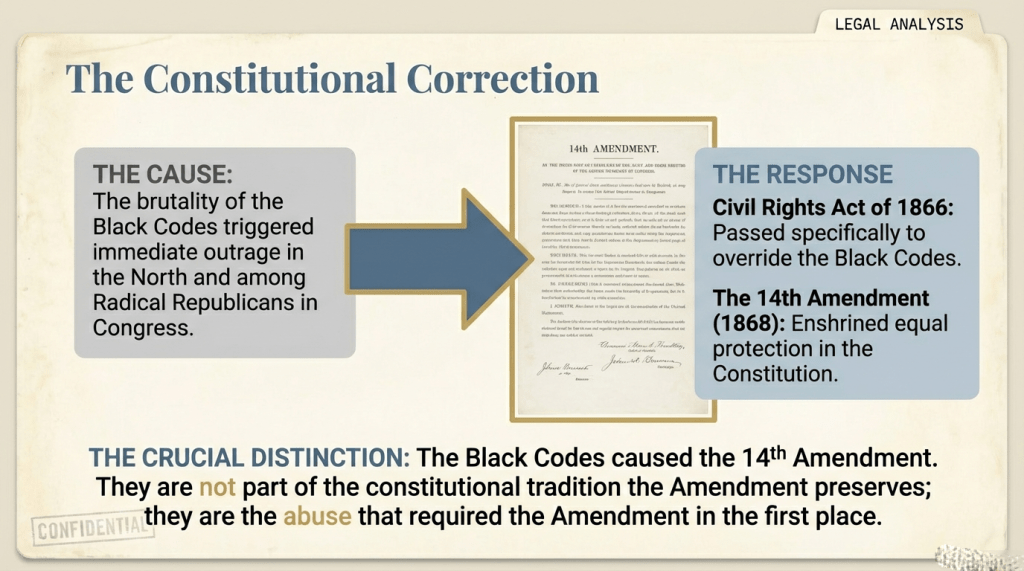

Northern reaction was swift, not because the North had suddenly discovered racial enlightenment, but because the Black Codes laid bare the lie that the war had settled the question of freedom. Reports filtered northward through newspapers, letters, and the agents of the Freedmen’s Bureau. The image of Southern states openly reconstructing servitude under another name proved politically explosive.

Congress responded with a ferocity that surprised President Andrew Johnson, who had taken a lenient approach toward the former Confederate states. The Civil Rights Act of 1866 was Congress’s opening salvo, declaring all persons born in the United States to be citizens and guaranteeing equal rights under the law. Johnson vetoed it. Congress overrode him. That override mattered. It signaled that Reconstruction would not be left to presidential discretion.

The Fourteenth Amendment followed, embedding the principles of citizenship, due process, and equal protection into the Constitution itself. It was a direct response to the Black Codes, a constitutional barricade erected where statutes had failed. The amendment was not abstract theory. It was a practical weapon forged in reaction to very specific abuses.

The Freedmen’s Bureau became the federal government’s eyes and ears on the ground. Its agents supervised labor contracts, adjudicated disputes, and in many areas functioned as an alternative legal system. Southern whites resented it deeply. Black communities often relied on it for survival. The Bureau’s reach was limited, underfunded, and politically contested, but its presence altered the balance of power, at least temporarily.

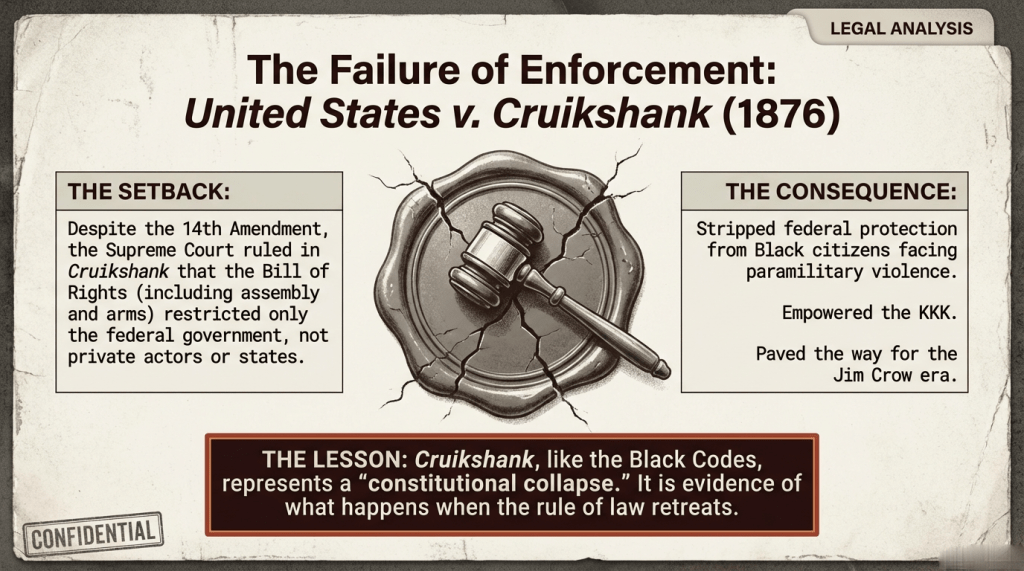

Yet the story does not move in a straight line toward justice. It veers. It doubles back. It stalls. The Supreme Court became the venue where Reconstruction’s promises were quietly narrowed. In 1876, United States v. Cruikshank arose from the Colfax Massacre in Louisiana, where white militias murdered scores of Black men defending a courthouse after a contested election. Federal prosecutors charged the perpetrators under the Enforcement Acts. The Supreme Court overturned the convictions.

The Court ruled that the Bill of Rights restricted only the federal government, not states or private actors. The federal government, the Court held, could not protect citizens from other citizens. The implications were devastating. Federal enforcement collapsed. White paramilitary violence surged. Reconstruction entered its long retreat.

Jim Crow followed, not as a sudden reversal but as a slow, methodical replacement. The Black Codes were repealed or rendered obsolete, but their logic survived. Poll taxes, literacy tests, segregation ordinances, and new labor controls carried forward the same goals with updated language. The ghost of the Black Codes did not leave the building. It simply changed rooms.

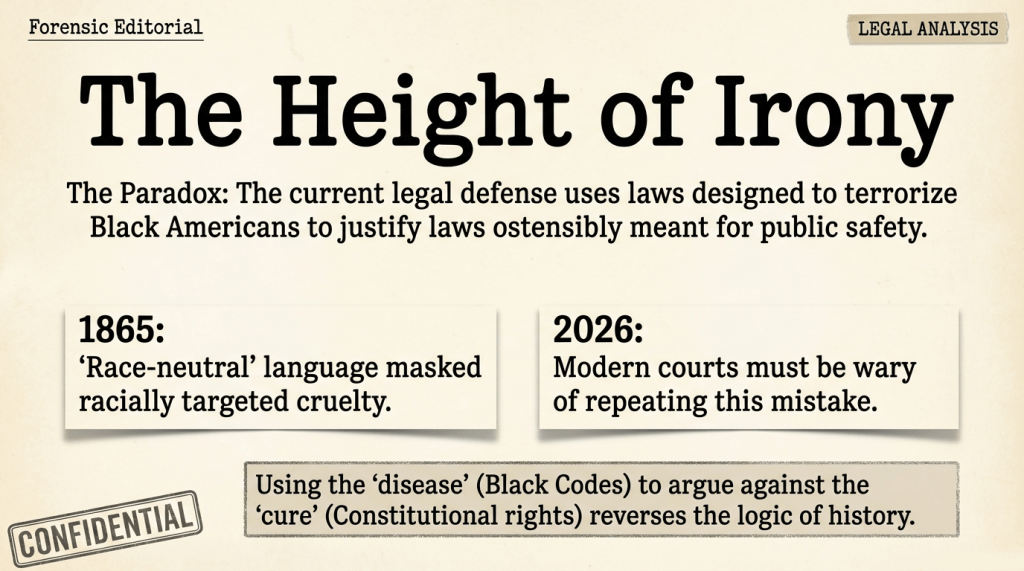

What makes this history particularly unsettling is how often it resurfaces in unexpected places. During Supreme Court oral arguments in January 2026, attorneys defending a modern firearm restriction in Hawaii cited post Civil War Black Codes as historical precedent. The reaction from the bench was swift and visibly uncomfortable. Justice Neil Gorsuch called the argument astonishing. Justice Samuel Alito noted the bitter irony of invoking laws designed to leave Black citizens defenseless against terror. Justice Clarence Thomas emphasized that the Fourteenth Amendment existed precisely to defeat such legislation. Even those defending the citation acknowledged the shameful origins of the laws, arguing that modern constitutional tests sometimes force lawyers to dig through the nation’s worst chapters to establish historical patterns .

This moment matters not because it settles any current legal question, but because it exposes a fundamental tension in American constitutional interpretation. History is not a curated museum exhibit. It is a warehouse, full of broken tools, stained ledgers, and objects whose original purpose should make us uneasy. Using history requires judgment, context, and an honest reckoning with intent.

The Black Codes were not mistakes or overreaches. They were deliberate strategies, crafted by men who understood exactly what freedom would mean if left unchecked. They remind us that law can be a weapon, quieter than a rifle, slower than a mob, but often more durable. They also remind us that progress is rarely clean. It advances through confrontation, retreat, and renewed effort.

For modern readers, especially those wary of tidy narratives, the Black Codes offer a caution without preaching. They show how quickly liberty can be narrowed by procedure, how equality can be hollowed out by technicalities, and how the absence of forceful enforcement can render even constitutional guarantees fragile. They also show that outrage, when informed and sustained, can change the course of law.

The past does not ask us to imitate it. It asks us to understand it. The Black Codes deserve remembrance not as relics, but as warnings etched into the legal grain of the nation. The hallway still exists. The banister still bears fingerprints. The cracks in the plaster tell a story for those willing to look.

The enforcement of the Black Codes did not depend solely on written statutes. It depended on people, sheriffs, judges, employers, constables, and neighbors who understood the spirit of the law even when the letter left room for maneuver. In many counties, enforcement was selective in theory and relentless in practice. White laborers might drift between jobs without consequence. Black laborers doing the same risked arrest. A white man could argue with a magistrate. A Black man could be jailed for tone alone. The law did not merely regulate behavior. It trained a population to internalize caution.

Freed people understood this almost immediately. Letters sent to Northern aid societies and the Freedmen’s Bureau speak of confusion and betrayal. Freedom had been announced with trumpet blasts and proclamations. What followed felt like a maze of fines, permits, passes, and threats. One Mississippi freedman reportedly told a Bureau agent that slavery had ended, but punishment had not. That observation, stripped of rhetoric, captures the lived reality better than any statute.

White Southern defenders of the Black Codes often framed them as necessary measures to maintain order. They argued that emancipation had unleashed chaos, idleness, and crime, claims repeated so often that they acquired the patina of common sense. The laws, they insisted, applied to everyone. The racial intent was denied with a straight face. Yet enforcement patterns told a different story. When laws target conditions disproportionately imposed on one group, neutrality becomes a legal fiction.

The courtroom became a theater where this fiction played out daily. Judges who had presided over slave societies now presided over free ones, or at least nominally free. Their assumptions did not evaporate with the ratification of an amendment. In many places, Black defendants faced all white juries, if juries were allowed at all. In others, summary proceedings replaced trials entirely. Speed was valued. Due process was treated as a luxury.

The economic consequences were profound. Wages remained depressed. Mobility was stifled. Sharecropping emerged as a compromise between plantation labor and independent farming, but it often trapped families in cycles of debt. The Black Codes did not invent these systems, but they provided the legal scaffolding that made exploitation predictable and enforceable. Contracts signed under threat of arrest were still contracts in the eyes of local courts.

Violence hovered over all of it, sometimes overt, sometimes implied. A freedman who challenged a labor contract might find himself arrested for vagrancy the next day. A community that attempted political organization might face night riders weeks later. Disarmament statutes ensured that resistance carried extraordinary risk. Even where firearms prohibitions were loosely enforced, the uncertainty itself was a deterrent.

This is where the story intersects with federal power in uncomfortable ways. Reconstruction policy oscillated between ambition and fatigue. Congress passed laws. The Army enforced them, for a time. Federal marshals made arrests. Klansmen were tried. Convictions occurred. Then the national mood shifted. Economic panic, political scandal, and electoral fatigue sapped Northern will. The violence receded just enough to be ignored.

The Supreme Court did not cause this retreat alone, but it codified it. Cruikshank was not an isolated decision. It was part of a broader judicial narrowing of federal authority. The message to Southern states was unmistakable. If discrimination could be framed as private action, federal remedies would fail. If violence could be localized, Washington would look away.

By the mid 1870s, the Black Codes themselves were largely gone from statute books, struck down, repealed, or superseded. Yet their functions persisted. Literacy tests replaced outright voting bans. Gun restrictions morphed into discretionary permitting regimes administered by hostile officials. Labor control shifted from explicit compulsion to economic coercion backed by local law enforcement. The forms changed. The objectives did not.

It is tempting, and comfortable, to see the Black Codes as a brief aberration, a grotesque spasm quickly corrected by constitutional progress. That narrative flatters the present and absolves the past too neatly. In reality, the Codes were an early draft of a system that endured for generations. They taught lawmakers how to regulate without naming race, how to punish without chains, how to preserve hierarchy under the cover of law.

Understanding this does not require assigning modern guilt or drawing straight lines to contemporary debates. It requires recognizing patterns. Legal systems reflect the values and fears of those who write them. They also outlive those intentions, sometimes in distorted forms. When modern courts wrestle with historical precedent, they are not excavating wisdom alone. They are unearthing compromises, cruelties, and contradictions.

That is why the recent Supreme Court exchange struck such a nerve. Citing the Black Codes as neutral historical examples forced an uncomfortable reckoning. These were not obscure municipal ordinances. They were instruments of racial domination, crafted in bad faith, enforced selectively, and designed to terrorize a population into compliance. Treating them as mere data points risks laundering their intent.

At the same time, pretending they never existed serves no one. The Black Codes matter precisely because they show how law can be bent toward injustice without abandoning legality. They remind us that constitutional amendments do not enforce themselves, that rights declared are not rights secured, and that vigilance is not a mood but a practice.

For veterans, for those who have sworn oaths to uphold constitutions rather than governments, this history resonates differently. It underscores that threats to liberty are not always foreign or dramatic. Sometimes they arrive as paperwork, stamped and signed, enforced by men who believe they are restoring order. The enemy is not always chaos. Sometimes it is complacency.

The Black Codes also complicate simple narratives of villainy and heroism. Not every white Southerner supported them. Not every Northerner opposed them consistently. Black communities were not passive victims. They organized schools, churches, militias, and political clubs whenever space allowed. They voted in remarkable numbers when permitted. They held office. They pushed back, legally and physically, until the space for resistance narrowed again.

The tragedy lies not in failure alone, but in partial success followed by retreat. Reconstruction showed what a multiracial democracy could look like under federal protection. The Black Codes showed how quickly that experiment could be undermined when protection was withdrawn. The lesson is not that progress is impossible. It is that it is reversible.

Walking away from this history without neat moral lessons is appropriate. The past rarely offers them. What it offers instead are textures, patterns, and warnings scratched into wood and stone. The Black Codes are one such warning. They whisper rather than shout. They remind us that freedom constrained can still be called freedom, and that law can be both shield and blade.

If the hallway feels dim, that is because it is meant to. Museums sanitize. Archives do not. The Black Codes belong to the archive, unpolished and unsettling. They deserve to be remembered not as footnotes, but as fingerprints left on the banister of American law, visible to anyone willing to look closely and honest enough not to flinch.

Leave a comment