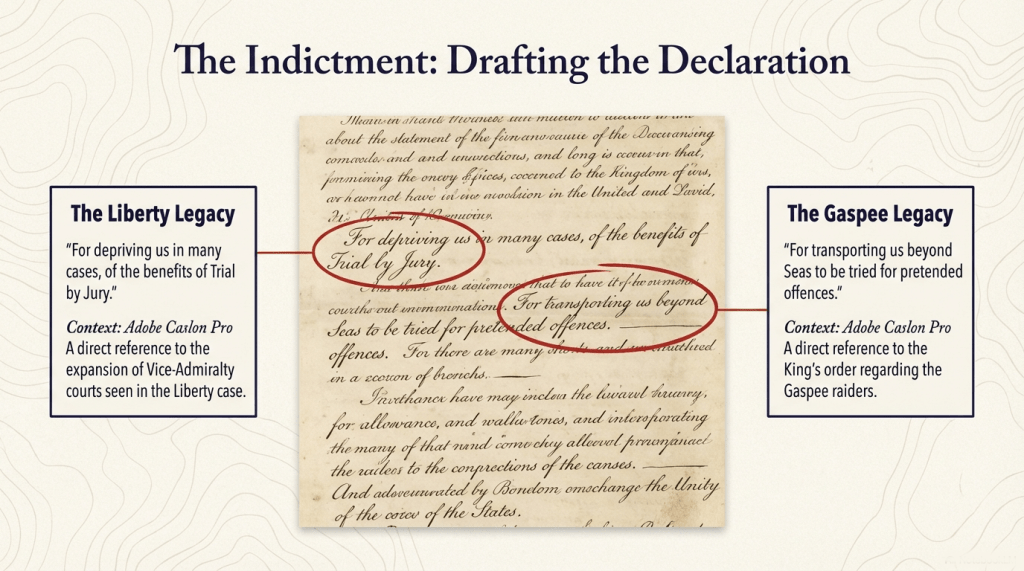

For depriving us in many cases, of the benefits of Trial by Jury

For transporting us beyond Seas to be tried for pretended offences

The Boston Tea Party has a talent for stealing the spotlight. It is visual, loud, and tidy in hindsight. Crates fly. Water splashes. Everyone agrees later that it was bold, necessary, and inevitable. It fits neatly into the American memory because it looks like rebellion is supposed to look.

But revolutions are rarely born in moments that photograph well.

Long before tea floated in Boston Harbor, the real fight had already begun, not in taverns or town squares, but in courtrooms and on docks. It began with paperwork, sworn testimony, and the quiet manipulation of legal systems most people assumed were solid and untouchable. The American Revolution did not start when colonists rejected British authority. It started when they realized British authority no longer felt bound by its own rules.

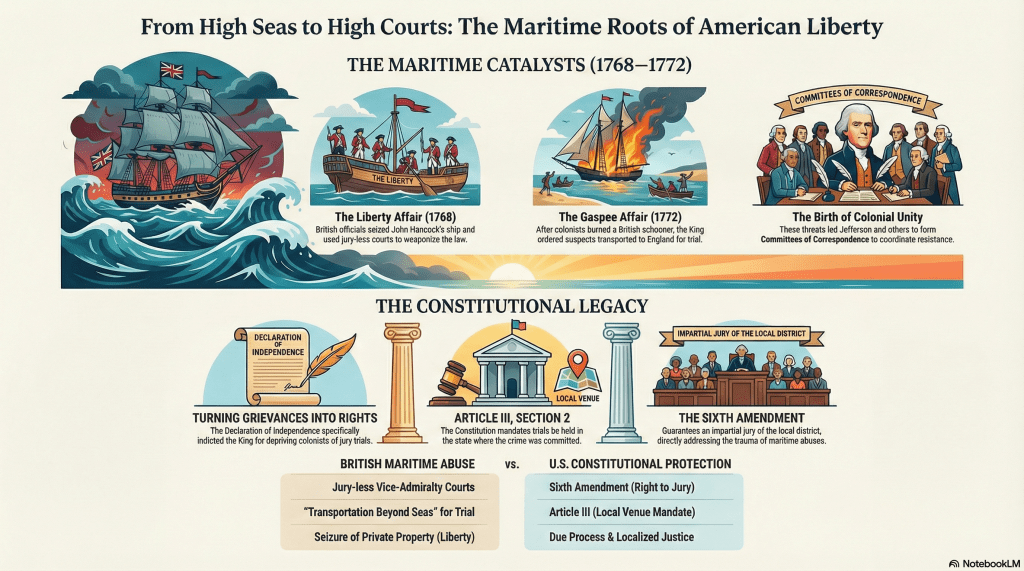

Two maritime incidents taught that lesson with brutal clarity. One involved a sloop named Liberty. The other, a schooner called Gaspee. Together, they stripped the empire of its moral camouflage and revealed the machinery underneath. Not taxation alone, not trade alone, but the deliberate use of the law as a weapon.

The Tea Party protested a tax. These earlier events exposed a philosophy.

To understand why that mattered so much, you have to stand on a Boston wharf on June 10, 1768.

Boston Harbor that morning looks busy, ordinary, almost peaceful. Ships crowd the docks. Barrels roll. Sailors shout. Merchants argue over invoices. It is a working port, not a battlefield. But the mood is tense in a way that is hard to describe and impossible to ignore. Everyone senses that something has shifted. British customs enforcement has grown sharper, more aggressive, less patient. The old habits, the quiet understandings, the winked-at practices of colonial trade are no longer being tolerated.

The Seven Years War is over, and Britain has won an empire. What it also won is debt, and Parliament has decided that the colonies will help pay for it. The problem is not merely the money. It is the method. Enforcement is no longer about regulation. It is about control.

Warships sit in the harbor, their presence officially justified as protection but understood locally as intimidation. Customs officers are no longer content to collect duties. They inspect, interrogate, and accuse. Suspicion is now policy.

Into this environment sails a sloop named Liberty.

The name is almost too perfect, which is part of the problem. Liberty belongs to John Hancock, the most prominent merchant in Massachusetts and one of the most visible critics of British policy. Hancock is not subtle. He lives well, dresses well, and signs his name like a man who expects history to remember it. That makes him successful, influential, and impossible for British officials to ignore.

The ship carries Madeira wine, a luxury import popular throughout the colonies and heavily taxed by British law. Madeira is not essential to survival, but it is essential to status, celebration, and commerce. It is also an ideal target. Smuggling is common, widely suspected, and rarely prosecuted with enthusiasm unless politics enters the equation.

On June 10, British customs officials decide politics has entered the equation.

A tidesman named Thomas Kirk claims that while the cargo was being unloaded, he was forcibly confined below deck, preventing him from supervising the transfer and ensuring that duties were paid. It is a serious accusation, and it rests almost entirely on his word. No crowd witnesses. No physical restraint is produced. Just testimony, recorded and accepted.

Based on that claim, the Liberty is seized.

This is not, in itself, unprecedented. What follows is.

Rather than leaving the vessel at the wharf, British officials tow Liberty away and anchor her beneath the guns of HMS Romney, a British naval vessel already resented in Boston for its role in impressing colonial sailors into naval service. The symbolism is unmistakable. This is not law as procedure. This is law backed by cannon.

The harbor notices. The town notices. Word spreads fast, and with it, anger.

For many Bostonians, this is no longer about whether Hancock paid a duty. It is about the spectacle of power. A civilian vessel, owned by a local merchant, has been seized and placed under military guard. Authority has shifted from ledger books to gun decks.

People gather, then more people, then thousands. Somewhere between two and three thousand colonists flood the area around the docks. They are not confused about why they are there. They understand exactly what message is being sent, and they understand that it is meant for them.

This moment matters because it exposes something essential. The Crown is no longer pretending that colonial consent matters. Enforcement has become performative, designed to intimidate as much as to regulate. The ship is not just seized. It is displayed.

Behind the noise and the anger, a deeper realization begins to take shape. If the government can act this way against someone as wealthy and connected as Hancock, it can act this way against anyone. If ships can be taken, property seized, and accusations made without meaningful local oversight, then the old assurances about English rights are no longer reliable.

What stands on the dock that day is more than a sloop and a crowd. It is a test. A test of how far Britain is willing to go, and how much the colonies are willing to tolerate before resistance becomes something more than complaint.

The Liberty Affair begins as a customs dispute. It does not stay one. It opens a door into a new understanding of power, one in which the law itself can be bent, relocated, and stripped of its safeguards when it becomes inconvenient.

And once that understanding takes hold, everything that follows becomes possible.

The seizure of Liberty did not happen in secret, and it did not happen gently.

British customs officials justified their action on the testimony of a single man, a tidesman named Thomas Kirk. Kirk claimed that while the ship’s cargo of Madeira wine was being unloaded, he had been forcibly confined below deck, unable to perform his duty and powerless to prevent smuggling. It was a serious allegation, and like many serious allegations in imperial history, it rested on remarkably thin evidence.

No corroborating witnesses emerged. No injuries were documented. No restraint was produced. But the accusation itself was enough. In an age when imperial authority was growing less patient with colonial resistance, suspicion carried more weight than proof.

Based on Kirk’s testimony, officials seized Liberty, the sloop owned by John Hancock. Had they stopped there, the incident might have remained a bitter but manageable dispute between a merchant and the Crown. Instead, they escalated.

Rather than leaving the ship moored at the wharf, customs officials ordered Liberty towed away and repositioned beneath the guns of HMS Romney. The Romney was not an abstract symbol. She was already despised in Boston for impressing colonial sailors into British naval service. Her presence represented coercion, not protection.

This was not merely an administrative decision. It was a public demonstration of force. The law was no longer being enforced quietly through ledgers and filings. It was now anchored under cannon.

Bostonians understood the message immediately.

To tow a civilian vessel away from its berth and place it under military guard was to announce that commercial disputes were no longer civil matters. Authority had crossed a line, and it did so deliberately, in full view of the town. The seizure of Liberty became a spectacle, and spectacles invite crowds.

Within hours, thousands of colonists gathered along the waterfront and nearby streets. Estimates range from two to three thousand, a staggering number for an eighteenth-century port town. This was not a mob searching for mischief. It was a crowd that knew exactly why it had assembled.

Customs collector Joseph Harrison and comptroller Benjamin Hallowell were singled out, not because they were personally cruel, but because they were visible embodiments of the new enforcement regime. They were jostled, struck, and humiliated. The violence was sharp but purposeful, a warning rather than a massacre.

The most telling act came later.

Hallowell’s pleasure boat, a symbol of official privilege and personal comfort, was dragged through the streets to Boston Common and burned in public. This was not random destruction. It was symbolic punishment. The people were answering authority in the only language authority had chosen to speak.

Terrified and suddenly aware of their isolation, customs officials fled Boston altogether, seeking refuge at Castle William, a fortified island installation in the harbor. That retreat mattered. It revealed how brittle British control had become. Officials charged with enforcing imperial law could no longer safely remain among the population they governed.

Order was restored eventually. No troops fired into the crowd. No executions followed. On the surface, the crisis passed. Beneath it, something fundamental had shifted.

Because the most dangerous part of the Liberty Affair did not occur in the streets.

It occurred in the courtroom.

The Crown did not bring charges against Hancock in a Massachusetts court. There would be no local jury, no panel of peers drawn from the community, no venue in which colonial norms and expectations could temper imperial ambition. Instead, British officials filed suit in vice admiralty court.

This choice was decisive.

Vice admiralty courts were not new. They had existed for generations to handle maritime disputes, prize cases, and violations of navigation laws. What made them dangerous in the colonial context was not their existence, but their expansion.

These courts did not use juries.

A single judge, appointed by the Crown and financially dependent on convictions for his income, presided over proceedings. There was no requirement to convince a community of guilt, only to satisfy a distant authority that an example had been made.

The government sought treble damages of nine thousand pounds. It was an astronomical sum, even for a man as wealthy as Hancock. The purpose was not restitution. It was annihilation. To ruin Hancock financially would be to neutralize him politically, and to warn others who might consider following his example.

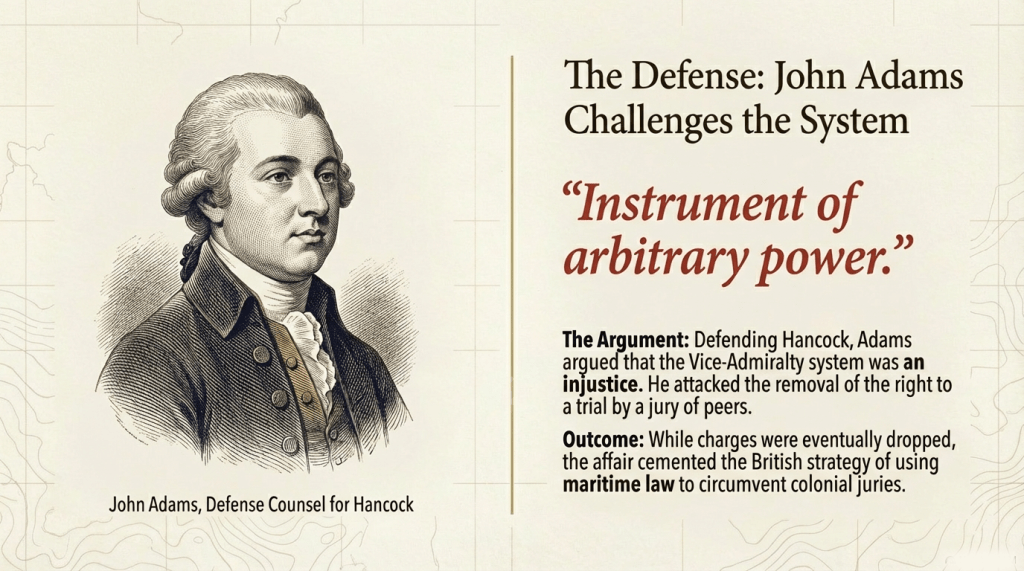

Hancock’s defense fell to John Adams, a lawyer who already understood that this case was not really about wine. Adams would later describe his early legal work as preparation for revolution, and here the lesson was unavoidable.

Adams attacked the vice admiralty system itself.

He argued that the absence of a jury was not a procedural detail. It was the central injustice. Trial by jury was not a colonial invention or a local preference. It was a foundational English right, older than Parliament, designed specifically to prevent the government from becoming prosecutor, judge, and beneficiary all at once.

Remove the jury, Adams argued, and the law ceased to be a shield. It became a weapon.

What made this argument so dangerous was its clarity. Adams was not accusing individual officials of corruption. He was accusing the system of being deliberately structured to produce obedience rather than justice. Vice admiralty courts were not neutral tools being misused. They were tools designed for precisely this purpose.

The Crown, in other words, was not bending the law. It was using the law exactly as redesigned.

The case dragged on. Witnesses faltered. Evidence thinned. The political cost of pursuing Hancock grew higher than the benefit. Eventually, the charges were dropped. No conviction was secured. No damages were paid.

On paper, Hancock won.

In reality, Britain had already lost something far more valuable.

The Liberty Affair demonstrated that maritime law could be used to bypass local justice entirely. It showed that juries, once assumed to be inviolable, could simply be removed from the process when they became inconvenient. It taught colonial leaders that their rights existed only so long as they aligned with imperial needs.

Worst of all, it exposed the next step.

Vice admiralty courts did not merely deny juries. They opened the door to transportation, the practice of sending accused colonists to Britain for trial. Distance itself became a tool of punishment. Witnesses could not follow. Communities could not watch. The accused vanished into the machinery of empire.

The Liberty Affair proved that this threat was no longer theoretical.

If the Crown was willing to seize ships under cannon, unleash admiralty courts without juries, and attempt financial ruin through distant judges, then nothing prevented it from putting colonial subjects on ships and sending them across the ocean in chains.

The case against Hancock collapsed, but the precedent stood.

The law had been revealed as flexible in the hands of power, and brittle in the hands of the people. Trust, once broken, could not be repaired by dropped charges or quiet settlements.

Boston remembered that lesson.

So did Rhode Island.

And when a British schooner called Gaspee ran aground and burned, the question raised by Liberty could no longer be avoided.

If the Crown could deny you a jury at home, could it deny you a home altogether?

That question would push the conflict from resistance into revolution.

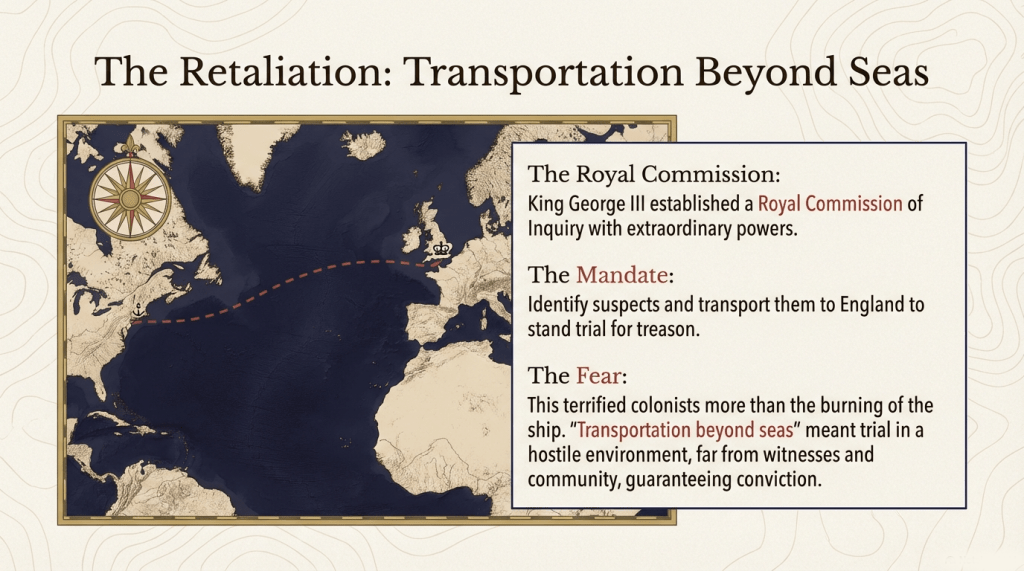

If the Liberty Affair taught the colonies that British law could be bent, the Gaspee Affair taught them something far worse. The law could be uprooted entirely and carried across the ocean.

On June 9, 1772, the British revenue schooner HMS Gaspee ran aground in Narragansett Bay. Groundings were not unusual in those waters, but Gaspee was no ordinary ship. She was widely hated throughout Rhode Island, known for aggressive patrols, arbitrary seizures, and an almost personal enthusiasm for harassing local trade. To many merchants and sailors, Gaspee represented everything that had gone wrong with British authority since the end of the Seven Years War.

That night, the tide did more than expose the ship. It exposed an opportunity.

A group of Rhode Islanders quietly assembled, including merchant John Brown and seasoned mariner Abraham Whipple. They rowed out to the stranded schooner under cover of darkness. This was not a riot. It was organized, deliberate, and disciplined. When the boarding party reached the ship, shots were fired. Lieutenant William Dudingston, Gaspee’s commander, was wounded. The crew was subdued and removed. Then the ship was set ablaze.

By morning, Gaspee was a blackened ruin, burned to the waterline.

In purely material terms, the damage was limited. One ship destroyed. No lives lost. The incident might have faded into local legend if not for what came next. Because this time, the Crown did not respond with paperwork or court filings.

It responded with fury.

King George III and his ministers viewed the burning of Gaspee not as a crime, but as a challenge. A British warship had been attacked, its officer shot, and imperial authority openly defied. To let that pass would invite repetition elsewhere.

The response was unprecedented.

The Crown established a Royal Commission of Inquiry, empowered to investigate the affair, identify suspects, and send the accused to England to stand trial. Not in Rhode Island. Not before colonial juries. In Britain, under British judges, far from witnesses, neighbors, and any sympathetic audience.

This was the threat that finally cut through the fog.

Colonists had protested taxes. They had resisted trade regulations. They had endured seizures and fines. But transportation beyond seas was something else entirely. It was exile disguised as justice. It meant being torn from one’s home, shipped across the Atlantic, and judged in a system designed to convict rather than understand.

This was the logical extension of vice admiralty courts without juries. The Liberty Affair had shown how local justice could be bypassed. The Gaspee Commission showed that geography itself could be weaponized.

The colonies reacted with alarm.

What frightened them was not the burning of a ship. Ships burned all the time. What frightened them was the realization that no colony stood alone anymore. If Britain could seize suspects in Rhode Island and try them in London, it could do the same in Massachusetts, Virginia, or anywhere else resistance took root.

This was no longer a series of local disputes. It was a systemic threat.

The response came swiftly, and tellingly, from Virginia.

Members of the Virginia House of Burgesses understood the danger immediately. Men like Patrick Henry, Richard Henry Lee, and Thomas Jefferson recognized that the Gaspee Commission was not aimed at Rhode Island alone. It was aimed at the principle of resistance itself.

They met not in the official halls of government, but at the Raleigh Tavern, a familiar refuge when royal authority made formal meetings inconvenient. There, they proposed something radical in its simplicity.

They created a permanent Committee of Correspondence.

This was not a social club or a debating society. It was a communications network, designed to ensure that no colony would face imperial pressure in isolation again. Letters would be exchanged. Threats would be shared. Responses would be coordinated. British actions would be treated not as local incidents, but as attacks on all.

Jefferson later reflected on the moment with characteristic clarity. The Gaspee inquiry convinced them that the most urgent measure was to come to an understanding with all the colonies. British claims were no longer to be treated as regional problems. They were a common cause.

That phrase matters.

Common cause meant shared fate. It meant that an assault on Rhode Island liberty was an assault on Virginia liberty, Massachusetts liberty, and eventually, American liberty. It transformed resistance from protest into solidarity.

Once that shift occurred, independence became imaginable.

The Committees of Correspondence spread quickly. Other colonies followed Virginia’s lead. Information moved faster. Suspicion hardened into certainty. Trust in British restraint evaporated. What had once seemed like isolated overreach now appeared as a coherent strategy.

By the time Parliament passed the Coercive Acts in 1774, the infrastructure of resistance was already in place. When shots were fired at Lexington and Concord, colonies did not hesitate to respond. They already knew how to speak to one another. They already believed their futures were bound together.

And when the Declaration of Independence was finally written, the fear of transportation beyond seas was not an abstract grievance. It was lived experience.

Jefferson would later list among the King’s crimes that he had “transported us beyond seas to be tried for pretended offenses.” That line did not come from theory. It came from Liberty. It came from Gaspee. It came from the moment the Crown revealed that it was willing to sever people from their communities to preserve control.

Burning ships did not cause the American Revolution.

But the attempt to drag colonists across the ocean in chains made independence unavoidable.

By the time the Declaration was signed, the lesson of the Gaspee Affair was clear. An empire willing to abandon its own legal traditions could no longer be trusted to protect liberty.

And once that truth was understood, separation was no longer radical.

It was necessary.

When Thomas Jefferson sat down in the summer of 1776 to draft what became the Declaration of Independence, he was not inventing grievances out of thin air. He was distilling memory. The document reads lofty now, almost abstract in its language of rights and principles, but its roots were stubbornly practical. The Declaration was written by men who had watched ships seized, courts manipulated, and legal protections quietly withdrawn while officials smiled and called it order.

The Liberty and Gaspee affairs mattered because they stripped away illusion. They showed that the conflict was not merely about taxation or representation, but about whether law itself would remain a shield for the people or become a cudgel for power. Jefferson understood that if independence were to be justified, it could not rest on scattered complaints. It had to show a pattern. Specific abuses had to be elevated into universal truths.

That is exactly what the grievances section of the Declaration does.

Jefferson takes concrete events, names no ships, mentions no harbors, and yet preserves their meaning with surgical precision. The goal is not to relitigate old cases, but to demonstrate that British rule had become structurally hostile to liberty. The King, not Parliament, is indicted because Jefferson is not arguing policy. He is arguing legitimacy.

Two grievances in particular stand as direct descendants of the Liberty and Gaspee affairs. They appear calm on the page, almost restrained, but they carry the weight of years of legal betrayal.

The first reads, “For depriving us in many cases, of the benefits of Trial by Jury.”

There is nothing poetic about that sentence. It does not need to be.

Trial by jury was not a colonial innovation. It was one of the oldest protections in English law, celebrated in charters, defended in sermons, and taught as a birthright. Colonists did not ask for juries as a privilege. They assumed them as a guarantee. The expansion of vice admiralty courts shattered that assumption.

The Liberty Affair exposed how easily juries could be removed when they became inconvenient. By shifting cases into maritime courts staffed by Crown appointed judges, British officials did not merely change venues. They changed outcomes. A single judge, financially dependent on convictions, replaced the collective judgment of a community. Guilt no longer had to be proven to peers. It merely had to satisfy authority.

Jefferson’s grievance does not say all juries were abolished. That would have been inaccurate. He says, “in many cases,” a phrase chosen with care. It acknowledges reality while condemning intent. The pattern mattered more than the total count. Once the government demonstrated that it could choose courts based on political convenience, no right was secure.

The Liberty case taught colonists that the law could be weaponized without being openly broken. That realization finds its way into the Declaration not as a footnote, but as a foundational charge. A government that deprives its people of juries does not merely err. It dissolves the consent that gives it authority.

The second grievance cuts even deeper.

“For transporting us beyond Seas to be tried for pretended offences.”

This line is shorter, sharper, and more ominous. It carries the shadow of exile.

The Gaspee Affair transformed an old fear into an immediate threat. When the Crown established a Royal Commission of Inquiry and asserted the power to send suspected colonists to England for trial, it crossed a line that could not be uncrossed. Distance itself became a form of punishment. To be transported beyond seas was to be severed from witnesses, community, and hope of impartial judgment.

Jefferson understood that this grievance struck at something primal. Being tried far from home was not simply inconvenient. It was dehumanizing. It treated colonial subjects as objects to be moved, not citizens to be heard. The phrase “pretended offences” matters here. Jefferson is not denying that laws exist. He is denying their legitimacy when enforced without justice.

This grievance speaks directly to the Gaspee Raiders, even though none are named. The threat alone was enough. No transportation ultimately occurred, but that did not matter. Power had revealed its intention. The colonies no longer judged British actions by outcomes alone. They judged them by capability.

Once a government claims the right to remove you from your home to stand trial elsewhere, the concept of local justice collapses. Law becomes portable. Rights become conditional. Liberty becomes negotiable.

Jefferson’s genius lies in how he universalizes these experiences.

He does not write as a Virginian or a New Englander. He writes as a representative of a people who have learned, through hard experience, that rights without enforcement are illusions. The grievances are framed not as colonial complaints, but as violations of natural law. They are addressed to the world because Jefferson understands that independence must be justified not just to Americans, but to history.

The Declaration does not call these acts mistakes. It calls them abuses. It does not argue that better administration might solve the problem. It argues that the system itself has become incompatible with liberty.

That is why these maritime legal battles mattered so deeply. They provided evidence. They transformed rhetoric into record. When Jefferson wrote that the King had shown himself “unfit to be the ruler of a free people,” he was not indulging in revolutionary flourish. He was summarizing a case already proven.

The Liberty Affair demonstrated that juries could be stripped away. The Gaspee Affair demonstrated that colonists could be dragged across oceans. Together, they answered the most dangerous question any people can ask.

What happens when the law no longer belongs to those it governs?

Jefferson’s answer was not violent. It was logical.

A government that denies juries and threatens transportation beyond seas has already broken the social contract. Independence, in that light, is not rebellion. It is withdrawal of consent.

By the time the Declaration was signed, the lesson was clear. The empire had chosen efficiency over justice, control over legitimacy. It had taught the colonies that rights existed only when convenient.

The Declaration simply took Britain at its word.

And once that truth was written down, there was no turning back.

When the authors of the Declaration of Independence addressed their case to “a candid world,” they were not indulging in rhetoric for its own sake. They were presenting evidence. The grievances were not emotional outbursts or philosophical abstractions. They were exhibits. Each charge against the King described a concrete pattern of behavior that, taken together, demonstrated something the Founders considered unforgivable. The Crown had ceased to act as a lawful government and had instead established what the Declaration called “an absolute tyranny.”

The Liberty and Gaspee affairs mattered because they provided proof that this tyranny was not theoretical. It could be seen, named, and traced through specific actions. Ships were seized. Courts were manipulated. Jurors were removed. Accused men were threatened with exile. These were not accidents of administration. They were the predictable results of a system that had come to value efficiency and control over legitimacy and consent.

The immediate legacy of these events was revolutionary justification.

By the time Thomas Jefferson drafted the Declaration, the argument had already been made in colonial newspapers, pamphlets, and legislative debates. Jefferson’s task was not to invent a case, but to organize one. The grievances section functions like a legal brief, carefully structured to show continuity of abuse rather than isolated mistakes. Liberty and Gaspee fit neatly into that structure because they illustrated how imperial power operated when challenged.

One phrase in particular reveals how deeply Jefferson had absorbed the lessons of these episodes. He accused the King of transporting colonists beyond seas “to be tried for pretended offences.” That word, pretended, was chosen with precision. Jefferson was not claiming that resistance involved no lawbreaking. He was arguing that laws enforced without justice, consent, or local legitimacy were themselves fraudulent.

From the British perspective, the Gaspee raiders had committed treason. They had attacked a Crown vessel, wounded its commander, and destroyed royal property. From the colonial perspective, those same actions were defensive. The ship had harassed local trade, enforced arbitrary seizures, and symbolized the erosion of lawful authority. Resistance, in that context, was not criminal. It was preservative.

This distinction mattered enormously. If the Crown could label resistance as treason and then define the venue, the judge, and the process for trying that treason, then legality became a closed loop. Power justified itself. Jefferson understood that such a system could never be reconciled with liberty. That realization shaped not only the Declaration, but everything that followed.

Independence did not end the problem. It merely transferred responsibility.

Once the colonies became states, the question that haunted the Founders was simple and terrifying. How do you prevent your own government from becoming the thing you just rebelled against? How do you ensure that the tools of law do not slowly transform into instruments of coercion?

The answer they arrived at was structural.

When the Constitutional Convention met in 1787, memories of vice admiralty courts and transportation threats were still fresh. Many delegates had lived through those years not as distant observers, but as participants. They had watched neighbors dragged into distant courts, fortunes threatened, and rights evaporate under procedural language. They were determined not to recreate those conditions under a different flag.

That determination appears first in United States Constitution, specifically in Article III, Section 2. The language is plain and deliberate. “The Trial of all Crimes… shall be held in the State where the said Crimes shall have been committed.”

This was not an afterthought. It was a direct response to imperial abuse.

The Gaspee Commission had shown how dangerous venue could be when controlled by distant authority. A trial held across the ocean was not merely inconvenient. It stripped the accused of witnesses, community oversight, and moral support. It turned justice into an endurance test. By mandating local trials, the Constitution closed that door deliberately and permanently.

But the Founders did not stop there.

The Constitution established the framework, but it was the Bill of Rights that engraved the lesson into American political DNA. The Sixth Amendment goes further than Article III. It guarantees not merely a local trial, but “an impartial jury of the State and district wherein the crime shall have been committed.”

Every word matters.

Impartial. Jury. State. District.

This was the anti Gaspee clause. It was the answer to Liberty. It was the recognition that justice is not only about laws on the books, but about who applies them and where. A jury drawn from the community serves as a brake on governmental overreach. It forces the state to persuade ordinary citizens, not just compliant officials. It embeds skepticism into the system.

To the Founders, a court without a jury was not simply incomplete. It was suspect. It concentrated power too efficiently. It eliminated friction, and friction was the point. Rights, they believed, survived precisely because enforcing them was inconvenient.

That belief remains one of the most important and most fragile inheritances of the American Revolution.

The Liberty and Gaspee affairs teach a lesson that remains uncomfortable even now. The structure of a court matters as much as the law it enforces. A perfectly written statute applied by a hostile or distant tribunal can become an instrument of arbitrary power. Due process is not a slogan. It is an architecture.

This is why venue matters. It is why jurisdiction matters. It is why the Founders obsessed over details that later generations often dismiss as technicalities. They had learned, the hard way, that governments rarely announce tyranny outright. They implement it procedurally.

The fear of being transported beyond seas captured something universal. It was not just fear of distance. It was fear of isolation. To be removed from one’s community is to be stripped of context. Neighbors know reputations. Local juries understand norms. Distant courts see only charges.

That insight remains relevant.

Modern debates about where defendants are tried, how jurisdictions are chosen, and whether legal proceedings are moved for convenience or security echo the anxieties of the eighteenth century. So do arguments over trade enforcement, tariffs, and the power of governments to disrupt livelihoods in the name of regulation. When people sense that enforcement mechanisms are being used to punish dissent rather than enforce law, the old alarms begin to ring.

Even discussions around deportation, extradition, and national security trials touch the same nerve. The question is not whether governments have authority. The question is how that authority is constrained. Once the state gains the power to choose venue strategically, justice becomes contingent.

The Founders would recognize that danger immediately.

They would remind us that cutting off trade, relocating trials, or redefining resistance as criminal behavior are not new tools. They are ancient ones. Empires have always relied on them. What made the American experiment different was not moral purity, but structural skepticism.

The Constitution assumes that power will be abused. It does not trust virtue. It trusts process.

That is the enduring legacy of Liberty and Gaspee.

The American Revolution was not fought solely with muskets and marches. It was fought on ship decks and in courtrooms, in arguments over who decides guilt and who controls procedure. Those battles rarely make for stirring paintings, but they shaped the nation more permanently than any single clash of arms.

The right to trial by a jury of one’s neighbors did not emerge from philosophical abstraction. It was carved out of lived experience, secured by people who had watched that right disappear under imperial convenience. It stands today not as a courtesy granted by government, but as a barrier erected against it.

When Liberty was seized and Gaspee burned, the colonies learned that freedom could be lost quietly, through paperwork and procedure, long before it was taken violently. The Constitution exists because the Founders refused to forget that lesson.

And as long as juries remain local, venues remain fixed, and courts remain accountable to the communities they serve, that lesson continues to hold.

Leave a comment