On the morning of January 17, 1955, the Thames River at Groton looked much as it always had in winter. Gray water, cold air, men in heavy coats moving with the practiced economy of sailors who knew their business. Nothing in the scene warned the casual observer that the age of naval propulsion was about to change course. At 11:00 a.m., the submarine tied to the pier eased herself free, not with drama or spectacle, but with a kind of quiet confidence. A few minutes later, a short message blinked out by signal lamp to the tender alongside. “Underway on Nuclear Power.” It was ten words, plain and unsentimental, and it marked the first time in human history that a vehicle moved under the control of sustained nuclear fission. The boat was the USS Nautilus, and the world did not yet grasp what had just slipped its moorings.

The man who sent that message, Commander Eugene P. Wilkinson, was not trying to be poetic. In fact, he had deliberately stripped the moment of poetry. Public affairs officers had prepared a page and a quarter of soaring prose to commemorate the event, full of carefully polished language about mankind entering a new era. Wilkinson read it, considered it, and rejected it. He understood something that historians sometimes forget. When something truly new happens, it does not need ornament. It needs accuracy. The Navy had a long tradition of plain speech at sea, and Wilkinson honored it. His message said exactly what had happened and nothing more. The restraint suited the moment.

The story of how Nautilus came to that pier begins well before that winter morning. Nuclear propulsion did not emerge from a committee or a fashionable theory. It came from one stubborn man and a conviction that the old limits were unacceptable. Captain, later Admiral, Hyman G. Rickover was not beloved, and he was not trying to be. He was relentless. He believed that engineering discipline was not a slogan but a moral obligation, that systems either worked as designed or they did not belong at sea. Rickover fought the Navy’s own bureaucracy as hard as he fought technical challenges. He demanded standards that made people uncomfortable. He insisted on personal accountability in an institution that often preferred diffusion of responsibility. Many officers resented him. History eventually sided with him.

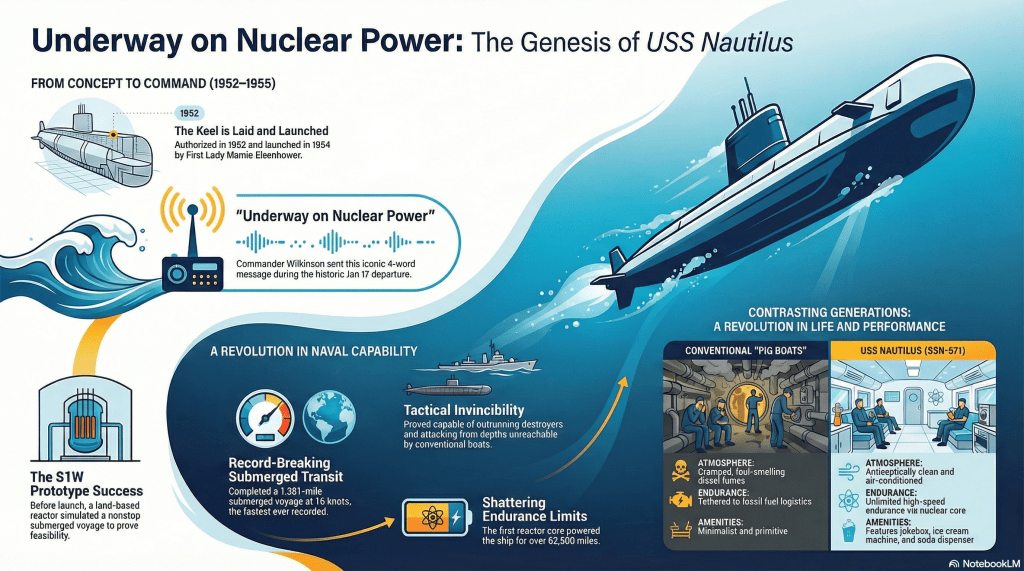

Before Nautilus ever touched salt water, the idea had to prove itself in the desert. At a remote site in Idaho, engineers built the S1W prototype reactor, a land based plant designed to replicate the conditions of a submarine at sea. Rickover insisted that it do more than run. It had to perform. In one famous test, the reactor operated continuously to simulate a nonstop submerged voyage from Newfoundland to Ireland. No diesel submarine could have attempted such a thing without surfacing repeatedly, revealing itself and exhausting its crew. The reactor did it quietly, steadily, without complaint. The principle was proven. The Navy now had to commit.

Authorization came in the Fiscal Year 1952 shipbuilding program, a moment that passed with little public attention. President Harry S. Truman laid the keel on June 14, 1952, a ceremonial act that tied the project to the highest level of civilian authority. When the boat was launched on January 21, 1954, it was Mamie Eisenhower who christened her, sending Nautilus sliding into the water amid the usual fanfare. By then, the hull already carried an ancient name. Nautilus had sailed in fiction long before she ever sailed in steel, and the Navy knew exactly what it was doing when it borrowed from Jules Verne. The implication was not subtle. This was a boat meant to go where others could not.

In the days leading up to January 17, 1955, there was no sense of a ceremonial countdown. The crew conducted what submariners call a fast cruise, four days of continuous operation while still tied to the pier. Systems were run, drills were conducted, and mistakes were corrected without mercy. It was a rehearsal for a kind of life that no one had ever lived before. A nuclear submarine was not simply a diesel boat with a better engine. It was a fundamentally different organism. Air conditioning replaced the damp, sour atmosphere of the old pig boats. Fresh water was no longer rationed like contraband. There was no smell of fuel oil clinging to clothes and skin. The boat was, by the standards of submariners, antiseptically clean.

There were still problems, of course. Nautilus was a prototype, built on a modified Tang class hull that had never been designed for the machinery now packed inside it. Pumps ran constantly. Machinery noise echoed through the pressure hull. She was faster and deeper than anything that hunted her, but she was also loud. Passive sonar would eventually make that a liability. She was also expensive. Nautilus cost roughly twice as much to build and operate as a conventional submarine, a fact not lost on budget minded officials in Washington. None of that mattered on January 17. What mattered was whether she would move as promised.

She almost did not. Just as the order to get underway was given, an engineering problem surfaced, minor but real. On a diesel boat, this would have been irritating but familiar. On the world’s first nuclear submarine, it carried a different weight. Wilkinson and his engineering team addressed it, corrected it, and proceeded. Nautilus eased into the channel, her reactor providing power without smoke, without vibration that reached the surface, without the visible signs of effort that had defined ships since the age of sail. When Wilkinson sent his message by flashing light to the tender Fulton at the state pier, it was less a declaration than a report. The future had arrived, and it worked.

The months that followed answered the question everyone was asking quietly. What could this thing really do. In May 1955, Nautilus departed New London and submerged for San Juan, Puerto Rico. She covered 1,381 miles in 89.9 hours at an average speed of sixteen knots, faster than any ship had ever traveled between those ports. She did it without surfacing. No snorkel. No pause. Just steady motion through the dark. During NATO exercises later that year, Nautilus humiliated conventional anti submarine forces. She outran destroyers, slipped beneath thermal layers, and delivered simulated torpedo attacks before escorts could react. It was not a fair fight, and everyone involved knew it.

The endurance figures were almost abstract. The first reactor core lasted two years and powered the ship for more than sixty two thousand miles. For submariners raised on battery endurance charts and fuel calculations, it was like stepping off a treadmill that had never stopped. The psychological impact was as important as the tactical one. Crews were no longer tied to the surface by necessity. The ocean became a continuous operating environment, not a place briefly tolerated between breaths.

It is tempting to romanticize this transformation, but the men who lived it were practical. They noticed the comforts, the jukebox, the soda dispenser, the ice cream machine, not because these were luxuries, but because they made long submerged operations tolerable. They noticed the absence of smell, the way clean air changed morale. They also noticed the noise, the maintenance demands, the constant vigilance required around a reactor that did not forgive carelessness. Nuclear power removed old constraints and introduced new responsibilities. Rickover had insisted on that trade from the beginning.

The significance of that quiet departure in 1955 did not fully reveal itself for several years. When Nautilus transited beneath the North Pole in 1958 during Operation Sunshine, the headlines finally caught up. That feat, dramatic as it was, rested entirely on the moment when Wilkinson sent his ten word message. Everything that followed, from ballistic missile submarines pacing silently beneath the oceans to aircraft carriers that no longer needed to refuel for decades, traced its lineage to that pier in Groton.

There is a useful comparison often made to Robert Fulton’s Clermont, the steamship that ended the tyranny of the wind. It is a fair comparison, as long as one remembers that such revolutions rarely announce themselves with fireworks. They begin with work, with argument, with people willing to be disliked in service of something that might fail. Nautilus mattered not because she was perfect, but because she worked well enough to change expectations. Once that happened, there was no going back.

Today, nuclear propulsion is so woven into naval operations that it risks becoming invisible. That invisibility is its own legacy. Ships stay at sea longer. Submarines operate where they choose. The logistics tail that once defined strategy has been shortened to the point of abstraction. All of it began with a commander who declined eloquence, an engineer who demanded rigor, and a boat that slipped quietly into cold water on a January morning. The fingerprints are still on the banister, if one knows where to look.

Leave a comment