Philadelphia was not just the place where rebellion happened. It was the machine that made rebellion louder.

You can romanticize Boston all you want, with its tea and its harbor and its fine talent for theatrical outrage. But by 1775 and certainly by early 1776, the center of gravity had shifted south. Philadelphia was where ideas stopped being parlor talk and started becoming objects. Inked, folded, stacked, and handed to strangers.

This was a working city. Not a court. Not a garrison. A place of tradesmen, merchants, apprentices, and men who knew the weight of tools in their hands. Ideas mattered here only if they could be built, copied, and moved. Philosophy that could not survive contact with a pressman’s hands did not last long.

That matters.

Because rebellion is not born in speeches. It is born in repetition. In the same words appearing again and again until they stop sounding radical and start sounding obvious.

Philadelphia had the presses to do that. Dozens of them. Not symbolic presses. Not gentleman printers dabbling in pamphlets as a hobby. These were industrial operations by the standards of the eighteenth century. Heavy iron presses bolted to the floor. Type cases worn smooth by decades of use. Men who worked twelve-hour days setting letters backwards so the rest of the world could read them forwards.

And when Common Sense hit the city, it did not float in on a cloud of Enlightenment rhetoric. It landed with a thump.

The printing press was not a metaphor. It was percussion.

Listen closely and you can hear it. The clack of movable type being set. The scrape of the ink balls. The grunt as the platen came down. Metal striking paper. Again. Again. Again. A rhythm you could set your watch by. A rhythm that did not care if the words were dangerous.

The ink was still wet when those pages were folded. Sometimes it is still tacky when they were sold. This was not literature meant to age gracefully. This was written with urgency built into the process. You could smell it. Oil. Ink. Paper dust. Sweat. This was not the silence of a library. This was noise.

And noise is what turns dissent into movement.

Every pull of the press was an act of multiplication. One idea becoming hundreds, then thousands. Each copy slightly imperfect, a smudge here, a broken letter there, but the message intact. In fact, the imperfections helped. They reminded the reader that this was made by human hands, not issued by authority.

Philadelphia amplified because it could not help itself. The city already ran on circulation. Goods. News. Rumors. Pamphlets. Sermons. Advertisements. Nothing sat still for long. Ideas moved because everything else did.

That is why Paine mattered here. Not because he was the only one saying these things, but because Philadelphia could repeat him faster than anyone else. Faster than London could suppress. Faster than governors could denounce. Faster than loyalists could argue back.

By the time anyone tried to answer Common Sense, it had already been answered by the press itself. Again. And again. And again.

This is the part we tend to forget. Revolutions are not powered by moments. They are powered by infrastructure. Someone has to own the press. Someone has to buy the paper. Someone has to risk prosecution to keep the presses running. Someone has to stand at a counter and sell treason one sheet at a time.

Philadelphia did all of that without blinking.

So when independence finally came to a vote, it did not arrive as a thunderclap. It arrived as a foregone conclusion. The sound of the press had already done its work. The argument had been rehearsed, memorized, and internalized. Not in Congress first, but in workshops, taverns, and kitchens.

That is the truth beneath the romance.

The Revolution was not shouted into existence. It was printed into it.

And Philadelphia was the drum.

Down in Philly where the January wind blows cold,

a little pamphlet’s turning silver into gold.

Tom Paine’s got a pen like a lightning rod,

shaking up the pews and the house of God.

Ink is wet on the printed page,

we’re the actors stepping on a brand new stage.

Hear the percussion of the printing press,

we’re cleaning up this colonial mess.

Thomas Paine was not lightning because he was refined. He was lightning because he was exposed.

He did not come wrapped in Latin or footnotes. He did not speak like a man auditioning for posterity. Paine spoke like someone who had been standing in the rain with everyone else, cold, tired, and increasingly angry that the roof was owned by someone three thousand miles away.

That is the mistake people make when they call him a philosopher. Philosophers explain the world. Paine translated it. He took arguments that had been locked up in elite conversation and dragged them into the street, shaking them until the loose change fell out.

He shook pews. He shook politics. He shook assumptions people did not even know they were carrying.

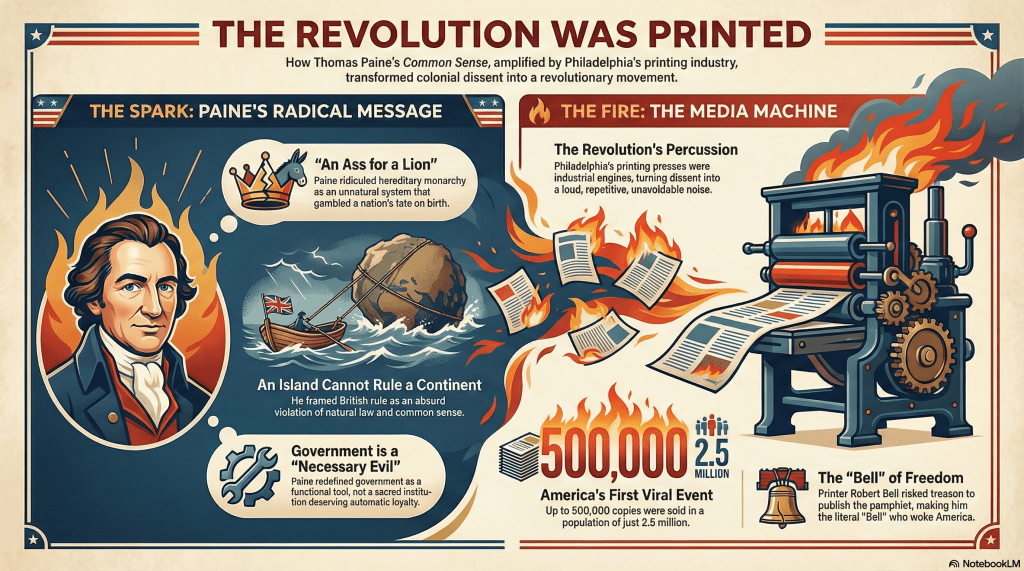

He asked questions that sounded obvious only after you heard them. Why should an island rule a continent. Why should birth decide authority. Why should loyalty survive abuse. These were not abstract ideas. These were daily irritations, finally given words sharp enough to cut.

And when those words needed a body, they found one at a print shop near Third and Walnut.

This was Robert Bell territory.

Bell was not a polished patriot. He was a printer with a nose for controversy and a willingness to gamble. His shop sat in the bloodstream of Philadelphia, where carts rattled past, voices overlapped, and news moved faster than authority liked.

That shop is where discontent stopped being private and became a signal.

Paper went in. Something alive came out.

Bell understood what Paine understood. Ideas do not matter until they move. A pamphlet unread is just expensive wrapping. But Common Sense did not sit still. It could not. Bell printed it aggressively, loudly, unapologetically. Not as a polite suggestion, but as a challenge.

And the presses responded like drums.

The sound mattered. Metal striking paper. Ink pressed hard. Each pull of the press felt like emphasis. This was not the quiet birth of a book. This was a broadcast.

Common Sense did something new in American political life. It went viral before anyone had a word for viral.

It was read aloud in taverns by men who could barely read at all. Passed hand to hand until the corners softened. Quoted from memory by people who had never owned a book. Argued over, shouted about, endorsed, cursed, and always discussed.

It traveled faster than rebuttals. Faster than proclamations. Faster than fear.

That is how you know it mattered. The British could not confiscate it fast enough. Loyalists could not answer it cleanly. Even its critics could not stop talking about it. Every attempt to contain it only helped spread it.

Common Sense did not ask permission to enter the conversation. It kicked the door and stayed.

And Paine became the lightning rod because lightning rods do one thing very well. They draw energy. They make the strike visible. They take the hit so the building does not have to pretend nothing happened.

People could argue with Paine. They could insult him. They could dismiss him as crude. But they could not unhear him. Once the question had been asked plainly, it lingered. Why not independence. Why not now.

By the time Congress caught up, the public already had the argument memorized.

This is what we forget when we talk about founding moments. The Declaration did not create the idea of independence. Common Sense normalized it. It made rebellion conversational. It made separation sayable.

That little shop near Third and Walnut was not just selling pamphlets. It was tuning the signal of a continent.

And once the signal was clear, there was no shutting it off.

The revolution did not begin with a vote.

It began when ordinary people started saying extraordinary things out loud, and realizing they were not alone.

This is not independence yet.

This is awareness.

This is the moment when people realize the argument is no longer theoretical, no longer something discussed by other men in other rooms. The moment when ordinary people understand that history has stopped asking their opinion and started assigning them a role.

Up to now, you could listen. You could nod. You could complain and go back to work. After this, you cannot unhear it. You cannot unknow it. The question has been placed in your hands.

Do you act, or do you let others act for you.

This is the instant the stage lights come up and the audience discovers there is no audience anymore. Everyone is in the play. No auditions. No understudies. Just a script still being written and a choice that will not wait.

Independence comes later.

First comes the unsettling knowledge that neutrality has already left the room.

Once authority is questioned, it rarely survives intact.

That is the danger Paine understood better than most, and why his words landed like broken glass. He did not nibble at the edges of British rule. He went straight for the load-bearing wall. Hereditary monarchy itself.

Now listen close to the argument he’s laying down,

about the foolishness of a hereditary crown.

Just because your daddy was a king of old,

don’t mean you’re entitled to the people’s gold.

An ass for a lion, it’s a royal disgrace,

nature don’t care about your ‘noble’ race.

If he’s a fool, then the whole land bleeds,

we’re planting better revolutionary seeds.

Thomas Paine did not argue that King George was a bad king. That would have been safe. Kings come and go, and the system survives. Paine argued something far more corrosive. That the system itself was unnatural, irrational, and dangerous, even when it worked as advertised.

Nature, Paine insisted, does not recognize bloodlines. Storms do not ask who your father was. Fire does not pause for a family tree. Ability is not inherited like silverware. Wisdom does not travel reliably through a womb.

Monarchy asked people to believe the opposite. That authority could be bred. That legitimacy could be transmitted by accident of birth. That a man could be born fit to rule millions simply because of who happened to precede him.

Paine did not treat this as tradition worthy of reverence. He treated it as an insult to common sense, and that phrase was chosen carefully.

Then came the line that made polite society wince and ordinary readers nod.

“An ass for a lion.”

Savage clarity. No cushion. No apology.

The image was unmistakable. A nation expects strength, judgment, courage, a lion at the helm. Hereditary monarchy promises that but delivers whatever chance happens to produce. Sometimes a lion. Sometimes an ass. Sometimes worse. And the people are expected to pretend the crown changes the animal.

Paine refused to play along.

Nature, he argued, does not promote by lineage. It selects by fitness, by capacity, by response to circumstance. To chain a society’s fate to bloodlines was not stability. It was gambling with loaded dice and calling the outcome sacred.

This was not abstract philosophy. Colonists had lived under the results. Policies made by distant men who had never seen America, never felt its winters, never understood its distances or dangers. Authority inherited, then exercised without understanding.

Once Paine said it plainly, it could not be unsaid.

Because once people begin asking why authority exists, rather than simply where it sits, everything changes. Loyalty stops being automatic. Obedience starts demanding justification. The spell breaks.

That is why monarchy could not survive intact once questioned this way. You cannot half doubt hereditary rule. Either birth confers legitimacy, or it does not. There is no comfortable middle ground.

Common Sense did not merely oppose a king. It taught readers how to interrogate power itself. And once people learn that skill, they do not forget it.

This is why governments fear ridicule more than resistance. You can fight resistance. Ridicule dissolves reverence. “An ass for a lion” did exactly that. It stripped away ceremony and revealed the animal underneath.

After that, crowns looked lighter. Thrones looked shakier. Authority looked provisional.

And that is the point where return becomes impossible.

Once authority is questioned openly, relentlessly, and in language ordinary people can repeat, it does not recover its old shape. It either transforms, or it collapses.

Paine understood that he was not just attacking a king. He was teaching the population how to look power in the eye and ask a question it had never been encouraged to ask before.

Why you?

And why at all?

The crown, Paine argued, was not a symbol of wisdom. It was a rusted relic, kept upright by habit rather than reason.

People bowed to it because they always had. Because their fathers had. Because questioning it felt improper, almost impolite, like criticizing gravity. But Paine insisted that habit is not proof, and repetition is not legitimacy. Something can endure for centuries and still be wrong.

Thomas Paine stripped the crown of its mysticism and found nothing underneath that deserved reverence. No divine glow. No natural order. Just power preserved by ceremony and fear of disruption.

That was the larger move. Paine did not merely criticize rulers. He redefined government itself.

Government, he said plainly, is not sacred. It is functional. It is a tool. And like any tool, it exists because something is broken.

He called it a necessary evil, and he meant both words.

Government exists because people fail. Because passions flare. Because disputes arise. Because not everyone behaves as they should. If humanity were perfect, government would be unnecessary. If people were angels, laws would be pointless.

That framing changed everything.

Rulers were no longer elevated figures dispensing order from above. They were managers of a problem that never fully goes away. Their authority was conditional, temporary, and always suspect. Not because power is always evil, but because it is always dangerous.

From that perspective, complexity was not sophistication. It was camouflage.

Paine favored simplicity over layers of office and inherited privilege. Law over men, rules over personalities. Systems that constrained power rather than glorified it. Government strong enough to function, but weak enough to be watched.

He rejected total control instinctively. Concentrated power, especially power justified by tradition rather than performance, always drifted toward abuse. History proved it. Human nature guaranteed it.

Then came the pivot.

Up to this point, the argument could still be framed as reform. Adjust Parliament. Change policy. Restore balance. Talk it out.

Paine refused that comfort.

He named the king himself as the problem.

Not a bad advisor. Not misguided ministers. Not temporary mismanagement. The crown. The office. The idea that one man, by accident of birth, could stand above the law and still claim to embody it.

Once that happened, reconciliation became theater.

Negotiation assumes a shared premise. Paine demolished the premise. If monarchy itself is illegitimate, then compromise is just delay dressed up as reasonableness. Debate becomes something you perform while time runs out.

This is the moment when the argument stops circling policy and lands on principle. You cannot argue your way back to loyalty once the structure of authority has been exposed as arbitrary.

Common Sense did not ask whether Parliament had gone too far. It asked why Parliament answered to the crown – any crown – at all. And once people followed that logic, there was no path back to reconciliation that did not require pretending the question had never been asked.

That is why this section mattered so much.

It told readers that the problem was not misrule. It was rule by mystique. Not policy errors, but the assumption that power must wear a crown to be legitimate.

After that, patience looked like cowardice. Delay looked like complicity. Waiting for permission from a broken system started to feel absurd.

This is the pivot where history tilts.

The argument stops being about fixing Britain’s government and becomes about replacing it. Quietly. Inevitably.

Not yet independence.

But no longer loyalty.

Now government at best is a necessary evil,

a badge of lost innocence for the people.

We need a little order, we need a little soul,

but we don’t need a tyrant in total control.

Keep it tight, keep it right, keep the power in the light

The sun never shined on a cause so grand,

it’s time to take a stand for the American land.

A small island ruling a continent?

No! It’s time for the Redcoats to pack up and go.

The period of debate is closed and done,

the battle for the future has just begun.

Get your musket, get your groove,

it’s time for the colonies to make a move.

Ideas are cheap.

Ink is not.

That is the lesson running beneath everything Paine wrote, and it is why his work mattered when others faded. You can have the sharpest argument in the world, but if no one is willing to set it in type, pull the press, and face the consequences, it stays where power prefers it. Silent.

Thomas Paine understood this instinctively. That is why his most dangerous sentence was not an insult to kings or a complaint about Parliament. It was the line that closed the door.

“The period of debate is closed.”

That was not bravado. It was a historical declaration.

Debate assumes legitimacy on both sides. Debate assumes time. Debate assumes that persuasion still matters. Paine was saying something colder and more final. The argument had already been made, absorbed, and accepted by the people who mattered most. Continuing to argue was no longer thoughtful. It was evasive.

Once that line was printed, neutrality stopped being a respectable posture.

Then came the argument that sounded rebellious only because people were used to hearing it framed that way. Paine stripped it of drama and treated it as physics.

A small island ruling a continent was not immoral in his telling. It was absurd. Against nature. A violation of scale. Mountains do not answer to pebbles. Rivers do not reverse themselves out of courtesy.

This was not an emotional appeal. It was natural law.

Distance alone made British rule irrational. Add ignorance, delay, and indifference, and the structure collapsed under its own weight. Paine did not ask readers to hate Britain. He asked them to notice reality.

Once people see an arrangement as unnatural, obedience stops feeling virtuous. It starts feeling foolish.

Then Paine did something bolder.

He lifted the argument off American soil and widened the lens.

This was not just about taxes or representation or colonial grievance. This was the “grand cause.” Not America’s cause, but humanity’s. A moment when an ordinary people had the chance to demonstrate that government could be built on consent rather than inheritance, on reason rather than ritual.

That is why Common Sense traveled so far, so fast.

Common Sense did not flatter its audience. It conscripted them into history. It told readers that what they were living through mattered beyond their farms and ports and families. That future generations would judge what they did with this moment.

That idea frightened elites. Not because it was violent, but because it bypassed them.

The spirit of the people is always the engine, and always the thing those in power fear most. It is unpredictable. It does not respect titles. It does not wait for permission. Loyalists dismissed it as mob sentiment. Officials treated it as noise. Paine treated it as fuel.

Once awakened, it does not go back to sleep.

But none of this happens without someone willing to print it.

This is where the story slows down, because this is where myth usually takes over. Bells. Towers. Bronze and ceremony. That comes later.

Before any of that, there was a shop.

Near Third and Walnut in Philadelphia, there was a printer who understood risk better than philosophy.

Robert Bell was not a saint. He was not selfless. He was ambitious, stubborn, and willing to gamble. But he understood something essential. Words do not spread themselves.

Bell risked treason charges. He risked his business. He risked his reputation. He even risked control of the very work he printed, because once Common Sense was loose, it belonged to the public, not the printer.

He made the noise loud enough to hear.

The revolution does not ring because a bell was cast. It rings because a printer pulled a lever. Again. And again. And again.

Each pull multiplied the argument. Each sheet carried the idea further than Paine could ever walk. Taverns. Churches. Workshops. Campfires. Read aloud. Argued over. Remembered.

Without the press, the song never plays.

This is the part history often cleans up. It prefers symbols to mechanics. But mechanics are where change actually happens.

The bell of freedom is not the Liberty Bell yet.

It is Robert Bell.

A man with ink on his hands, debt on his mind, and a press that did not care whether the words it printed were safe. Only whether they were legible.

The awakening of a continent did not begin with a proclamation or a vote. It began with the decision to print something that could not be taken back.

Before there was a bell in the tower, there was a Bell in a shop.

And that was enough to wake a continent.

Perhaps the sentiments contained in the following pages, are not yet sufficiently fashionable to procure them general favor; a long habit of not thinking a thing wrong, gives it a superficial appearance of being right, and raises at first a formidable outcry in defence of custom. But the tumult soon subsides. Time makes more converts than reason. – Thomas Paine, Common Sense

Leave a comment