January 1776 arrives without ceremony and without mercy. Winter grips the colonies, the war sputters uncertainly, and George III, in a speech meant to steady the empire, instead hardens the lines. The King declares the colonies to be in rebellion. Not misguided children. Not aggrieved subjects. Rebels. Once that word is spoken aloud, the old language of reconciliation begins to rot on the page.

Into this moment drops a pamphlet that does not argue politely. It does not hedge. It does not genuflect before tradition. Common Sense lands like a thrown brick through a stained glass window. It takes a political argument that had lived in taverns and committee rooms and shoves it into the hands of ordinary readers. It tells them, in plain words, that monarchy is not merely inconvenient but absurd. That independence is not reckless but necessary. That the future will not be inherited, it will be taken.

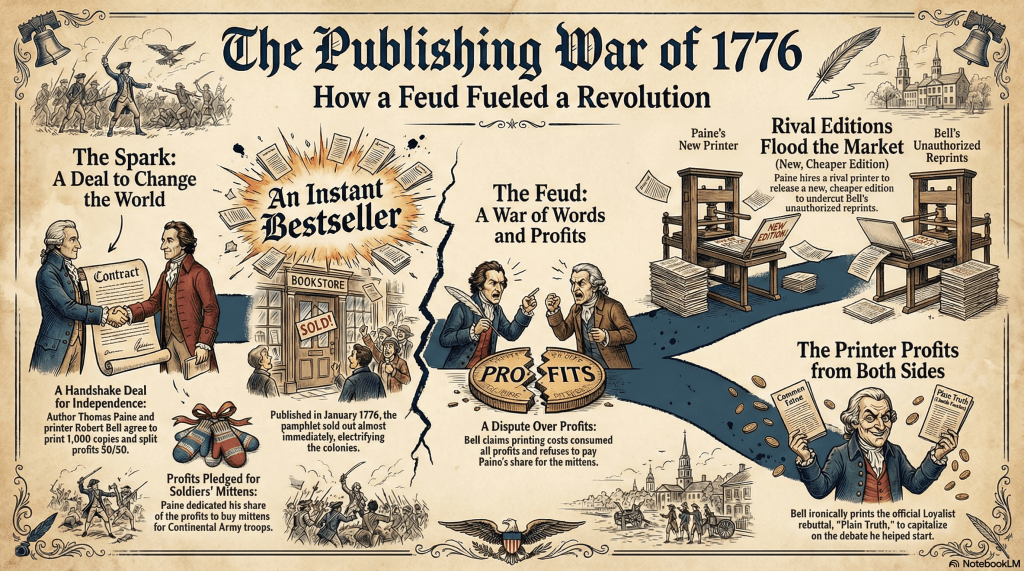

Yet the story behind Common Sense is not a clean morality play of noble author and grateful public. It is a street fight conducted with ink. It involves Thomas Paine, newly arrived and chronically short of money, and Robert Bell, flamboyant, mercurial, and permanently advertising. It involves a deal over profits pledged to buy wool mittens for freezing soldiers, a bitter feud over who owned words once they were printed, and the strange fact that the same printer who launched the most radical argument for independence also printed its most famous Loyalist rebuttal, Plain Truth.

What The Frock – The Musical

This is not just a story about ideas. It is a story about presses, profits, piracy, and patriotism. The physical production and dissemination of Common Sense and Plain Truth in Philadelphia exposes the messy ecosystem of the American Revolution, where conviction and commerce were never fully separable, and where the fight for independence was also a fight over who controlled the printed word.

Philadelphia in the 1770s is not yet the romantic city of liberty plaques and orderly tours. It is loud, argumentative, crowded, and soaked in ink. By the eve of the Revolution, roughly twenty three printing shops operate within the city. That is an astonishing density for a colonial town. News, sermons, broadsides, pamphlets, handbills, and advertisements circulate at a pace that would have startled earlier generations.

Printers occupy a peculiar social niche. They are craftsmen, yes, but also editors, translators, political actors, and cultural gatekeepers. They read more than most people, write better than many, and sit at the choke point between idea and audience. The great dynasties, the Bradfords and the Franklins, have already demonstrated that a printing press can be a lever on history.

Into this world steps Robert Bell, arriving from Scotland around 1767 and promptly refusing to behave like a respectable tradesman. Bell styles himself a “Professor of Book Auctioneering,” a title that tells you almost everything you need to know. His auctions are performances. There is beer. There is heckling. There is what Bell proudly calls buffoonery. He sells books as “Jewels and Diamonds,” and he sells them loudly.

Bell’s business model is aggressive and disruptive. He prints cheap American editions of popular English works that had previously been expensive imports. Blackstone’s Commentaries. Rasselas. He breaks monopolies and undercuts prices. He advertises relentlessly, appealing to “Sentimentalists” and the “Sons of Science.” Bell does not whisper culture into existence. He shouts it into the street.

Thomas Paine arrives in America only a year before Common Sense appears. He edits the Pennsylvania Magazine, writes essays, and nurses a growing fury at the distance between political rhetoric and political reality. His initial plan is modest. A series of newspaper articles responding to the King’s speech. Reasoned. Sequential. Safe.

Enter Benjamin Rush, physician, patriot, and professional accelerator of events. Rush sees immediately that Paine’s argument needs a better title and a bolder format. He suggests Common Sense. He also suggests a printer unafraid of risk. Robert Bell. Rush calls him the “Republican printer,” a man reckless enough to publish something that might be called treason before breakfast.

The agreement they strike is simple and fated for disaster. Bell will print the first edition, one thousand copies. Profits will be split evenly. Paine pledges his share to buy wool mittens for Continental soldiers freezing during the Quebec expedition. If the pamphlet fails, Paine will absorb the losses. Idealism meets the balance sheet.

Common Sense appears on January 9 or 10, 1776, priced at two shillings. It sells out almost immediately. Bell advertises a new edition within days. By January 20, it is already clear that this is not an ordinary pamphlet. It is an event.

Paine’s argument is not subtle. He attacks the King as a tyrant and the peerage as parasites. He declares the English constitution “rotten.” He insists that reconciliation is not merely impossible but immoral. Most dangerously, he argues that only an open declaration of independence will make foreign alliances possible. France and Spain will not back a family quarrel. They might back a revolution.

The language is accessible. The tone is relentless. The effect is electric. This is not a pamphlet to be skimmed. It is read aloud. Passed hand to hand. Argued over. The prairie fire metaphor is tempting, and misleading. Fires still need fuel, and they spread unevenly.

Success ruins the partnership almost instantly. When Paine asks for his share of the profits to buy the promised mittens, Bell claims there are no profits. Printing costs have consumed everything. Paine is owed nothing.

Paine does not believe him. Bell does not budge. Matters escalate quickly. Paine plans a new edition with substantial additions, including a response to Quaker objections. Bell tells him flatly that he has no business with the work anymore. Bell prints an unauthorized second edition.

Paine responds by taking his manuscript to Bell’s rivals, Bradford brothers, Thomas and William. They print the official new edition at half the price, one shilling, designed explicitly to undercut Bell. Paine adds a note denouncing Bell’s edition as unauthorized.

Bell retaliates in public. Advertisements appear in the Pennsylvania Evening Post accusing Paine and the Bradfords of “dishonest malevolence.” Bell prints a third edition that pirates Paine’s additions and pads the pamphlet with essays by other authors. The war is no longer ideological. It is personal.

There is no copyright law to appeal to. Ownership of words is a moral argument, not a legal one. Years later, Paine will write to George Washington, using this episode to argue for literary property laws. Bell, Paine recalls, told him plainly that once printed, the work was no longer his.

The controversy produces its mirror image. James Chalmers, writing under the pseudonym Candidus, publishes Plain Truth, a methodical Loyalist rebuttal to Common Sense. Monarchy is defended. Independence is portrayed as reckless fantasy.

And Robert Bell prints it.

Criticism follows immediately. How can the “Republican printer” give aid to the enemy? Bell responds with a printed defense of press liberty, quoting an older pamphlet by Benjamin Franklin, also titled Plain Truth. The argument is classic and inconvenient. A free press does not pick sides. It prints arguments and lets the public fight them out.

In London, the debate is packaged whole. Publisher John Almon bundles Common Sense and Plain Truth together in June 1776 so British readers can judge whether Americans are prepared for independence. The argument crosses the Atlantic as a matched set.

The Bell versus Bradford struggle reveals a city hungry for text. Bell’s auctions sometimes feature thousands of volumes. His catalogs read like intellectual menus. Readers consume political argument alongside novels, sermons, and philosophy. Revolution is not only fought with muskets. It is read into existence.

The oft repeated claim that Common Sense sold 150,000 copies is likely exaggerated. Distribution was concentrated in cities and regions with dense print networks. Even so, its reach was extraordinary. Think less universal saturation, more strategic ignition. Influence is not measured only in numbers.

Bell dies in Richmond in 1784 while selling books on the road. His press is auctioned. Fittingly, it is purchased by Mathew Carey, another immigrant printer, another believer in the power of cheap print.

Paine’s end is lonelier. His later religious writings alienate former allies. His involvement in the French Revolution stains his reputation. Few attend his funeral. History, having used him, moves on.

The fight between Robert Bell and Thomas Paine was not a sideshow. It was the Revolution in miniature. Profit versus principle. Control versus diffusion. Order versus velocity. Bell’s hunger for sales and Paine’s hunger for change collided, and in that collision ideas escaped containment.

In a world without copyright, Common Sense could not be recalled or controlled. It spread because it could be stolen. Like a modern viral post, it escaped its creator and became public property. Paine lost money. Soldiers lost mittens. Independence gained momentum.

History is rarely tidy. It is printed on cheap paper, argued over in public, and sold at auction with beer. And sometimes, that is exactly enough.

Leave a comment